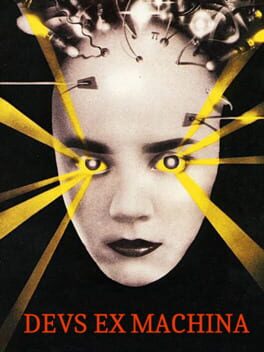

Deus Ex Machina is a 1984 ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64 game with a heavy focus on sensory experience above interactive gameplay.

Reviews View More

Certainly unique, but not definitively interesting.

the graphics are interesting but [its obvious to me that this gamez ambition is severely hampered by the fact that 80s graphics are limited n basic af. i respect what they were trying to do tho, n the concept, music, etc. are awesome

Don't expect too much, it's not that 'profound' as an art piece and it doesn't have much worth as a game however it's undoubtedly an important and interesting piece of the history of electronic arts.

What a weird game, if you can even call it that. It really is more of a electronic, visual experience, I guess.

I didn't play this game, as I had difficulties finding it online and I don't think my bosses at work would be too thrilled if I downloaded whatever this is onto the company computers, so I opted instead to watch RZX Archive play through it, while also reading through the provided manual and different British nostalgia pieces on it.

Deus Ex Machina is weird, but it's definitely not boring, always keeping your attention with flashing visuals and the iconic ZX Spectrum color palette. The cassette tape that comes with it gives the game a full stereo soundtrack and voice overs, all from some of England's favorite actors and creators. It definitely puts the game above and beyond in sound design from other games at the time, but I imagined the extra cassette tape would be annoying to try and get matched up to the game. According to fans who grew up with the game though, they had no issue with the sound matching up, and many have fond memories of how immersive it all was, especially at the time.

I don't really know what to say about Deus Ex Machina, nonetheless. It's definitely something... fun? No... Philosophical? Well... as much as stepping on giant words that say WAR and EVIL can be... Interesting? Not really... as its discussion on what it means to be a part of mankind has been discussed a million times before, most doing a much better job at it too, but the idea of analyzing mankind through a way in which the player can interact with the media itself is pretty unique. Unfortunately, I feel Deus Ex Machina was a little too early in trying to achieve what it does, as the gameplay elements are either barely existent or too advanced to properly do what the game wishes of you (I don't know what they were thinking doing a jumping segment from a face forward perspective...). The manual has sections where they're supposed to describe the gameplay you need to do in order to match the story, and even they have parts where they essentially say, "Just follow along until the next part" keeping players in the dark about whatever they're supposed to do as the screen produces seizures in front of them.

The music on the cassette tape is awful, I'm sorry, all I could think about was they had the ability to put any variety of music on that, with some of England's best artists to their disposal, and they chose to put whatever THAT was. Ugh.

I really can't be too mean to Deus Ex Machina though, as it genuinely is one of the first of its kind, and it IS interesting seeing how they were able to portray different things to try and help immerse the player. People online who talk fondly about growing up with the game like to talk a lot about how crazy the audio was to play with when it came out, and how it was never like something they had seen before, taking more from it on how different it was than about the actual game itself. It really is an experience over being a game, and I can see how it could be fascinating to come across. At the end of the day though, I would much rather spend my time playing Marble Madness or something with more gameplay than go through Deus Ex Machina again, no matter the graphically difference. I'm glad to say I experienced it though!

2/5

I didn't play this game, as I had difficulties finding it online and I don't think my bosses at work would be too thrilled if I downloaded whatever this is onto the company computers, so I opted instead to watch RZX Archive play through it, while also reading through the provided manual and different British nostalgia pieces on it.

Deus Ex Machina is weird, but it's definitely not boring, always keeping your attention with flashing visuals and the iconic ZX Spectrum color palette. The cassette tape that comes with it gives the game a full stereo soundtrack and voice overs, all from some of England's favorite actors and creators. It definitely puts the game above and beyond in sound design from other games at the time, but I imagined the extra cassette tape would be annoying to try and get matched up to the game. According to fans who grew up with the game though, they had no issue with the sound matching up, and many have fond memories of how immersive it all was, especially at the time.

I don't really know what to say about Deus Ex Machina, nonetheless. It's definitely something... fun? No... Philosophical? Well... as much as stepping on giant words that say WAR and EVIL can be... Interesting? Not really... as its discussion on what it means to be a part of mankind has been discussed a million times before, most doing a much better job at it too, but the idea of analyzing mankind through a way in which the player can interact with the media itself is pretty unique. Unfortunately, I feel Deus Ex Machina was a little too early in trying to achieve what it does, as the gameplay elements are either barely existent or too advanced to properly do what the game wishes of you (I don't know what they were thinking doing a jumping segment from a face forward perspective...). The manual has sections where they're supposed to describe the gameplay you need to do in order to match the story, and even they have parts where they essentially say, "Just follow along until the next part" keeping players in the dark about whatever they're supposed to do as the screen produces seizures in front of them.

The music on the cassette tape is awful, I'm sorry, all I could think about was they had the ability to put any variety of music on that, with some of England's best artists to their disposal, and they chose to put whatever THAT was. Ugh.

I really can't be too mean to Deus Ex Machina though, as it genuinely is one of the first of its kind, and it IS interesting seeing how they were able to portray different things to try and help immerse the player. People online who talk fondly about growing up with the game like to talk a lot about how crazy the audio was to play with when it came out, and how it was never like something they had seen before, taking more from it on how different it was than about the actual game itself. It really is an experience over being a game, and I can see how it could be fascinating to come across. At the end of the day though, I would much rather spend my time playing Marble Madness or something with more gameplay than go through Deus Ex Machina again, no matter the graphically difference. I'm glad to say I experienced it though!

2/5

at some point i thought i was watching a dont hug me i'm scared episode

i dont know what ive played....but i like it