The game begins with your character, whose family has just moved to the area, entering his new school for the first time. After class, you accidentally run into a conservative-looking girl wearing glasses. She introduces herself as Mizuho, but you can't help but notice her striking resemblance to your dream pop idol, Miho Nakayama. You pick up a good-luck charm Mizuho dropped to give back to her, then make a startling revelation - your photographer brother took a picture of Miho carrying the exact same charm! You go to the music room to confront her with this evidence - and this is where the true challenge of the game begins.

Released on

Genres

Reviews View More

I prefer Yuki Saito.

Games discourse anticipated a lot of contemporary turns in pop psychology by representing dating and bishoujo games as simulations of emotional manipulation, and the extended guilt-tripping sequence in this game almost feels like a parody based on this sentiment. It's most interesting, I think, as a relic of the sort of low-budget PC-style game development the FC Disk System briefly brought to the Japanese mainstream: it's a game that could have never justified cartridge production, a predecessor of the promotional Flash tie-in. The goon trio was also kind of cunty.

This game is so unbelievably interesting and influential, that I wish it was much better than it is.

One of the most important dating simulator games ever made that created this genre of games and is responsible for many more dating simulators to be created and appreciated.

A cool and simple game that entertain to conquer your beloved 2D waifu.

I still think it's a somewhat impressive game for the NES for capturing the idea of the game well and for some of the game's music that moved me.

If you want to enter this world of dating simulator games, it's a good one, despite being very rudimentary.

Still, it's worth giving this classic a try.

A cool and simple game that entertain to conquer your beloved 2D waifu.

I still think it's a somewhat impressive game for the NES for capturing the idea of the game well and for some of the game's music that moved me.

If you want to enter this world of dating simulator games, it's a good one, despite being very rudimentary.

Still, it's worth giving this classic a try.

The ancestor to the modern Dating Sim (the first game to even be labeled as one), this little idol game with a surprising amount of big names behind it may not have the most complex story that'd likely be considered played out today or gameplay for something that uses the same style as the Adventure games that came before it (although in certain aspects like the Cafe Date, Piano, and Roof, it loves to use the same amount of obtuseness...) but it makes up for it with the little nuances in how you have to go about conversations and dates with the Nakayama Miho/Miporin. I like it, even if it's a little trial and error. Thankfully losing a date puts you right back at the start of that conversation. It's just the final one you gotta watch out for which is not so forgiving.

As the founder of the Dating Simulator, it's a neat piece of history. As a game itself, it's a solid concept with a few frustrating elements. If you're just curious for the history, don't be afraid to use a guide if you get stuck!

Thanks for contributing to the invention of an entire genre, Miporin!

As the founder of the Dating Simulator, it's a neat piece of history. As a game itself, it's a solid concept with a few frustrating elements. If you're just curious for the history, don't be afraid to use a guide if you get stuck!

Thanks for contributing to the invention of an entire genre, Miporin!

This review contains spoilers

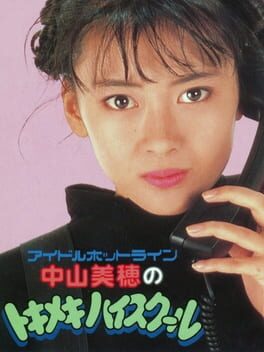

Nakayama Miho no Tokimeki High School [1987] is not one for the ages. It was made in either 3 months or start from finish in 2 weeks flat, depending on which interview you believe, immediately after Hironobu Sakaguchi finished work on Final Fantasy [1987], and right before Yoshio Sakamoto, creator of Metroid [1986], moved on to Famicom Detective Club: The Missing Heir [1988]. (There’s something deliciously perverse to me about covering this game as part of this canon without covering any of those more well-known ones.) It was meant to be disposable, transient junk food. It wasn’t even built to hang around later than February 1988. It is so deliberately tightly tied to its exact time and place, both by and from that exact cultural context. Integral to the game was its fax contest and automated telephone answering machines. While we can now play it while completely ignoring the first and substituting the second with a transcript of what you would have gotten if you called, we cannot write this all off as a mere sales gimmick easily disposed of. This aspect of the game was the germ of the whole rest of it, even preceding the idea of a licensed celebrity tie-in, and the telephone got co-star status on the cover with that same titular idol.

As you might have gathered from the remarkable paucity of J-Pop in the 1980s playlists, I must admit I am not very steeped in the cultural context this game comes out of — frankly, I don’t even grasp which order to put romanized Japanese names in, I just go along with what I see other writers doing — so I really hit the books for this one. The most important thing I was made to understand about idols is that, contrary to how I was thinking about it, the music is important but not central to either the workday of an idol nor the reception of the audience. Rather, idolhood is very multimedia, and many argue that its primary vector is not music but actually our old friend television. Its traditional doubled-edged qualities of its transient immediacy, its intimacy borne of inviting its characters into your living room and spending years regularly getting to know them, its industrial-scale replication of image, and its blurring of the lines between advertising and content are all expertly leveraged by the studios that manufacture idols, are key to the phenomena of the idol, and most of those qualities besides maybe the last are also in evidence at Tokimeki High School.

--- MUSICAL INTERMISSION: Nakayama Miho – Linne Magic [1987]

Unlike Takeshi Kitano’s relationship to Takeshi’s Challenge [1986], there is no pretense that Nakayama Miho had any creative input onto the game, any author function that dominates the text. Though they are both celebrities, there are different expectations of a middle-aged male comedian and actor and a teenaged girl pop singer and actress. Along with the gendered and age-based expectations, we expect unique perspective out of comedians, while a pop music audience is at peace with the idea that pop singers may very well sing a song they had nothing to do with making. (Nakayama Miho had only just written her first song in 1987.) It is readily apparent that she did a photoshoot for the game’s cover and its (very stylish) manual, some advertisements, lent her voice to the answering machines, and that’s probably the entire extent of her involvement. We are, basically, meant to understand Tokimeki High School as another story Nakayama Miho is acting in, even though she’s not actually being filmed performing.

And yet, somehow, the pitch of this game is that you the audience member will get to meet and spend time with the “real” Miho. We try to glimpse the authentic person through the manufactured media. This is the paradox of the star in general, AND of the simulation in general, and it’s this productive tension Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School is driven by. Its fictional premise is a kind of Hannah Montana [2006-2011] set-up: everyone knows of Nakayama Miho, pop idol, but she leads a double life as normal teenager Takayama Mizuho, courtesy of a pair of Clark Kent glasses. You (and the manual is very insistent that this player character is You, Full Stop,) attend the same high school as Mizuho, giving You privileged access to the “real” Miho.

This is only the beginning of what can be described as a postmodern hall of mirrors haunted by elusive phantoms. Not only are both Mizuho and Miho costumes worn for different social contexts in-fiction, they are both obviously equally fictional characters made from scratch out of pixels and words. Even that’s not the core truth of the matter, because whatever the material basis of image production is, it exists in concert and referent to Nakayama Miho, or more accurately the complex of other images the audience has of her. There is no center to orient yourself towards, just a complicated web of performances to parse. This reaches its dizzying heights when Miho leaves You a digital handwritten note to call a phone number to hear the actual Miho’s voice read from a script asking You out on a date with her virtual counterpart, in-character as Mizuho, to go see a fictional movie starring Miho as presumably yet another fictional character. She says she wants to experience her own movies from the perspective of a “normal” person, so she scripts this whole elaborate and extremely abnormal scenario and casts You in it as her scene partner. It’s as though the hope is that convoluting the matter as much as possible will somehow cut to the quick, will bamboozle you into living in the moment and not thinking about it too hard.

Nakayama Miho herself is easily the most complex character we’ve yet seen here in our walk through gaming history. Her only serious competition comes from the ranks of Deadline [1982], which I called at the time “a cast of untrustworthy stereotypes,” but who do have qualities that have nothing to do with the plot and interior personalities at conflict with themselves to be parsed. This game hinges on the particularities of Miho’s mood and mind, on careful attention to her television-sized close-ups and considering how she might feel.

…But complex doesn’t mean convincing. She has opinions and moods that come from vaguely the same place, but any illusion of an actual psychology is brutally punctured by the fact that, sooner or later, by design, you are going to have to brute-force your way through a conversation with her like she’s a combination lock. The skin peels off and you must see the gears and levers that actually constitute Miho. It’s nigh Brechtian.

Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School is shockingly linear. Prior adventure games we’ve seen heavily emphasized exploration, but the “move” option in this game simply brings you immediately to the next place where your character needs to be for the story to progress instead of having the player look for it. If there is something you have to see or do or stay, the story stays stuck right in place until you do it. The whole first act offers the player no choice in their actions or thoughts at all, except for those which have no ramifications like lingering for extra examination or dialogue. You have to swap the disk side three times before you get an actual branch point.

Even once the game opens up even a little, it prunes its tree very aggressively, leaving little room for variation in story until the endgame. It is just as linear, except now you can fail to walk the line. It’s deliberately cinematic, except the actors keep flubbing their lines so you have to take it from the top. You are, as ever, walking through an almost-invisible maze the developers built for you, divining its shape through bumping up against its edges when all else fails. There’s a scene where You get kidnapped by a girl in a white dress that recalls the “but thou must” scenes from Dragon Quest [1986], but with the dark twist that you know You really, really don’t want to say yes but all options that amount to “no,” while implemented, simply circle you back around to the question again.

Like Alter Ego [1986], this is a game based around choosing what You do next from its menu of options, and not one that is all that interested in the wide variety of possible paths that implies for either player self-expression or hypertextual contrast, but rather in taking a hard stance on the correct narrow path to follow with your life. It is, essentially, another didactic text with a distinct point of view about how a person, here a male teen, ought to comport themselves. It’s simulation as rehearsal, hence the repetition. For example, “touching” (groping) people or making a droolingly horny facial expression are offered as options but are always incorrect choices, inputs that are either quietly discarded or lead to a failstate or are openly chastised.

Walking its line gets stranger the further in you go, as it bends to fit the needs of a contrived plot. You get into a stupid dispute with Miho where neither You nor her are actually at fault, but you’re angry with her and she’s contrite, and the difficulty is that you actually aren’t offered the option to be upfront and forthright, or forgiving and ready to move on. The ultimate solution to how to patch up your relationship instead begins with making Miho start to cry. Then You insult her and act outraged, maximally seething, and only this course of action leads her to ask for your forgiveness and say she can’t bear the thought of never seeing You again. Through this route, she actually ends up saying the exact same lines verbatim which typically precede a game over, except this time You actually get to keep talking for no clear reason, and then You have to ask her “don’t you understand how I feel” while, importantly, not using any of the facial expressions that would actually indicate any feeling. What we are meant to glean about how to treat people from this hash is unclear at best and bad at worst.

It just seems like the game has a particular dramatic confrontation in mind and warps around it, in actually a pretty familiar and normal way to anyone who’s seen a kinda-lousy story where characters have no good reasons to be mad at each other, but the writers feel some kind of pressing need to gin up conflict from thin air as story grist, whilst also being too precious to actually have something go seriously awry. It’s a classic move of what I would say is just flat out classic bad storytelling, though there are many ways to recover from and redeem or forgive the beat, such as: making the irrationality part of the point, or giving some kind of reason for prolonged misunderstanding as in a farce, or just moving past the beat quickly enough that the audience doesn’t have time to get irritated and nit-picky about it. What Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School does instead is really dwell on it, and encourage the audience to deeply consider the emotions and logic of the scene, which seem more and more emotionally incoherent the longer the player goes over it. Instead of having the shape of the story and the things the player does in it determined by the formal structures of the game, they’ve gone and mounted a conventional story beat onto the adventure game trial-and-error framework which stretches it out until it rips apart.

This rehearsal dynamic is most easily navigated and clearly made apparent the first time the player has any effective choices at all, when they have their first substantial dialogue exchange with Mizuho/Miho, having just figured out the double-act. You get a bunch of A/B choices of what to say, and the choice is typically whether or not to talk about Miho’s celebrity status. Throughout the whole game, Miho gets really touchy and visibly angry if You ever bring up her job, and if you persist you head right to a game over. (In a shocking generosity for the era, this game has you start scenes over if you fail instead of the entire game.) The message is clear and agreeable: if you happen to meet a celeb in the flesh, just treat them like a normal person, don’t geek out.

However, this means the game exists in a sustained state of self-denial. The whole reason we are here, in and out of fiction, is that we are interested in Nakayama Miho due to her celebrity. But we must constantly dance around the subject, never addressing the facts head-on except when the game takes over for us. In fact, we are actively confronted with the possibility of speaking honestly and then quite deliberately suppressing it. The A/B choices demand to be read not as opposing pairs but in superposition and synthesis, as running commentary on one another, the polite conscious and the basal unconscious, each simultaneously possible and possibly simultaneous. This is the split personality of Miho/Mizuho, mechanized.

There’s actually a lot more significant pairs in the cast. The rich snob girl, Erika, and the rich snob boy, Masaomi. The strict vice principal, and the cuddly principal. The trio of Erika’s sycophants, and the trio of adult male thugs who work for Erika. There’s another character, Sadakichi, who’s your Mizuho — your shadow. Especially in the early game, he tags along making observations that your character cannot because your character is meant to be You, and You don’t know the kids at this new school. He has the same fannish predilections as You, but he is not as lucky, always a moment too late, so that You get to the plot first. His chubby looks are an object of ridicule from the first lines of the game, which marks him out permanently as someone who does not get to participate in romance or desire. Besides that, the game seems reasonably endeared of him. He gets a cool motorcycle! Sadakichi is at once a model of the ideal consumer audience and stigmatized.

Sex is also pointedly repressed and denied. It’s broached twice in the first act. Once, You run into the vice principal, an absolute tightwad, who gets embarrassed when You discover him carrying a porno mag around in his vest. It’s a natural tidy irony: the guy droning on and on about propriety and procedure is just poorly suppressing his own sleaziness and trying to do extend that same censorious attitude to everyone else. Secondly, and earlier, right before Your very first spoken exchange with Miho, while You’re just looking for the girl who dropped something when You bumped into her, Sadakichi hears some girls in a classroom and thinks that might be who you’re looking for. So, You peek in, and surprise: it’s two teen girls in their underwear getting dressed in a classroom after school for some reason! Miho shows up immediately after this shot for the second time, the first where You actually get to conversate with her at all.

This is… less natural and tidy. It’s a PG-13 riff on a gag I’d more expect in a bawdy college sex comedy of this era than the achingly chaste soap-operatic high school rom com this game otherwise is. It’s not entirely clear to me why it’s here, so pardon me while I overthink one ultimately insignificant shot while not even mentioning entire characters and subplots. It’s a wide shot with big bugged-out eyes, clearly more comically awkward than gratuitously titillating, but it’s not particularly funny because there’s no development of the premise towards any kind of point at all. Because it’s an honest accident around an inexplicable situation, it doesn’t really reflect on anyone’s decisions and thus doesn’t, say, characterize either Sadakichi or the player character as a bit of a sleaze. Because it’s so unpredictable, maybe it’s meant to juice the rest of the game with a certain charge; if not an erotic one, then one where any random thing could be around the next blind corner. Maybe it’s there because a frazzled attitude around sex is part of being 17. The language of cinematic montage connects this image directly with the appearance of Miho. This can either be interpreted 1) as supplementary — “for all their gentlemanly behavior, boys only have one thing on their mind when it comes to cute girls,” that though this is an accident it still formally commentates on the boys’ goals or unconscious desires, like the A/B choices — or 2) as contrast — this is not a game where you will be seeing Miho in her underwear, that’s for certain: not only is she a real-life 17-year-old celebrity, but by immediately following something a little prurient with polite navigation of choppy conversational waters you can argue it’s signalling to the audience that this story isn’t THAT, it’s THIS. Indeed, your relations with her are to be so very chaste that You don’t even get to successfully kiss before the end of the game.

Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School is often-enough cited as the first proper dating sim: The meat of the gameplay revolves around navigating dialog trees, and though that sounds pedestrian enough now, this is actually the first we’re seeing of it on this blog, though it’s not a new thing in 1987 Japan, and the ultimate goal of navigating these dialog trees is to master interpersonal social behavior such that You can successfully secure and perform dates with a virtual girl whose emotional state is tracked and displayed in some detail. I’m not a subject matter expert so I won’t make that genre call for myself, and besides, it’s not as though they sat down to make a dating sim because that concept didn’t exist yet so it could hardly inform its shape. Its clearest historical influence is once again from the Portopia Serial Murder Case [1983/1985] lineage. Portopia even has phone calls to gate progression!

However, there is another lineage of Japanese computer adventure games, the one I already mentioned back in that article: the pornos. An accidental-peeping-Tom scene would have a pretty obvious reason to be in one of those, maybe that’s what’s being expressly denied. History happened over there too, porn games didn’t sit still for 4 years either, and as best as I can tell they beat this game to the punch on the whole dialog-tree-navigation gameplay by about a year or two in titles like Kudokikata Oshiemasu [1986]. It’s not certain, but it’s certainly not impossible that that’s where the designers lifted the concept from: Sakaguchi and Square as a whole got their start in the computer adventure-gaming market, with their last computer game before working on consoles, Alpha [1986], having some softcore erotic elements. Perhaps Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School brings up and denies pornography as an allusion, a head nod, but that’s a pretty strong and spicy claim to be backed up by no evidence whatsoever, so let’s just call it a rhyme. Regardless, the dating sim and the porn game would remain strongly associated into the future, giving even chaste rom-coms like these a whiff of dirty and disreputable salaciousness that dogs the genre to this day.

-----

Originally posted on my blog, [https://arcadeidea.wordpress.com/2022/06/27/nakayama-miho-no-tokimeki-high-school-1987/](Arcade Idea.)

As you might have gathered from the remarkable paucity of J-Pop in the 1980s playlists, I must admit I am not very steeped in the cultural context this game comes out of — frankly, I don’t even grasp which order to put romanized Japanese names in, I just go along with what I see other writers doing — so I really hit the books for this one. The most important thing I was made to understand about idols is that, contrary to how I was thinking about it, the music is important but not central to either the workday of an idol nor the reception of the audience. Rather, idolhood is very multimedia, and many argue that its primary vector is not music but actually our old friend television. Its traditional doubled-edged qualities of its transient immediacy, its intimacy borne of inviting its characters into your living room and spending years regularly getting to know them, its industrial-scale replication of image, and its blurring of the lines between advertising and content are all expertly leveraged by the studios that manufacture idols, are key to the phenomena of the idol, and most of those qualities besides maybe the last are also in evidence at Tokimeki High School.

--- MUSICAL INTERMISSION: Nakayama Miho – Linne Magic [1987]

Unlike Takeshi Kitano’s relationship to Takeshi’s Challenge [1986], there is no pretense that Nakayama Miho had any creative input onto the game, any author function that dominates the text. Though they are both celebrities, there are different expectations of a middle-aged male comedian and actor and a teenaged girl pop singer and actress. Along with the gendered and age-based expectations, we expect unique perspective out of comedians, while a pop music audience is at peace with the idea that pop singers may very well sing a song they had nothing to do with making. (Nakayama Miho had only just written her first song in 1987.) It is readily apparent that she did a photoshoot for the game’s cover and its (very stylish) manual, some advertisements, lent her voice to the answering machines, and that’s probably the entire extent of her involvement. We are, basically, meant to understand Tokimeki High School as another story Nakayama Miho is acting in, even though she’s not actually being filmed performing.

And yet, somehow, the pitch of this game is that you the audience member will get to meet and spend time with the “real” Miho. We try to glimpse the authentic person through the manufactured media. This is the paradox of the star in general, AND of the simulation in general, and it’s this productive tension Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School is driven by. Its fictional premise is a kind of Hannah Montana [2006-2011] set-up: everyone knows of Nakayama Miho, pop idol, but she leads a double life as normal teenager Takayama Mizuho, courtesy of a pair of Clark Kent glasses. You (and the manual is very insistent that this player character is You, Full Stop,) attend the same high school as Mizuho, giving You privileged access to the “real” Miho.

This is only the beginning of what can be described as a postmodern hall of mirrors haunted by elusive phantoms. Not only are both Mizuho and Miho costumes worn for different social contexts in-fiction, they are both obviously equally fictional characters made from scratch out of pixels and words. Even that’s not the core truth of the matter, because whatever the material basis of image production is, it exists in concert and referent to Nakayama Miho, or more accurately the complex of other images the audience has of her. There is no center to orient yourself towards, just a complicated web of performances to parse. This reaches its dizzying heights when Miho leaves You a digital handwritten note to call a phone number to hear the actual Miho’s voice read from a script asking You out on a date with her virtual counterpart, in-character as Mizuho, to go see a fictional movie starring Miho as presumably yet another fictional character. She says she wants to experience her own movies from the perspective of a “normal” person, so she scripts this whole elaborate and extremely abnormal scenario and casts You in it as her scene partner. It’s as though the hope is that convoluting the matter as much as possible will somehow cut to the quick, will bamboozle you into living in the moment and not thinking about it too hard.

Nakayama Miho herself is easily the most complex character we’ve yet seen here in our walk through gaming history. Her only serious competition comes from the ranks of Deadline [1982], which I called at the time “a cast of untrustworthy stereotypes,” but who do have qualities that have nothing to do with the plot and interior personalities at conflict with themselves to be parsed. This game hinges on the particularities of Miho’s mood and mind, on careful attention to her television-sized close-ups and considering how she might feel.

…But complex doesn’t mean convincing. She has opinions and moods that come from vaguely the same place, but any illusion of an actual psychology is brutally punctured by the fact that, sooner or later, by design, you are going to have to brute-force your way through a conversation with her like she’s a combination lock. The skin peels off and you must see the gears and levers that actually constitute Miho. It’s nigh Brechtian.

Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School is shockingly linear. Prior adventure games we’ve seen heavily emphasized exploration, but the “move” option in this game simply brings you immediately to the next place where your character needs to be for the story to progress instead of having the player look for it. If there is something you have to see or do or stay, the story stays stuck right in place until you do it. The whole first act offers the player no choice in their actions or thoughts at all, except for those which have no ramifications like lingering for extra examination or dialogue. You have to swap the disk side three times before you get an actual branch point.

Even once the game opens up even a little, it prunes its tree very aggressively, leaving little room for variation in story until the endgame. It is just as linear, except now you can fail to walk the line. It’s deliberately cinematic, except the actors keep flubbing their lines so you have to take it from the top. You are, as ever, walking through an almost-invisible maze the developers built for you, divining its shape through bumping up against its edges when all else fails. There’s a scene where You get kidnapped by a girl in a white dress that recalls the “but thou must” scenes from Dragon Quest [1986], but with the dark twist that you know You really, really don’t want to say yes but all options that amount to “no,” while implemented, simply circle you back around to the question again.

Like Alter Ego [1986], this is a game based around choosing what You do next from its menu of options, and not one that is all that interested in the wide variety of possible paths that implies for either player self-expression or hypertextual contrast, but rather in taking a hard stance on the correct narrow path to follow with your life. It is, essentially, another didactic text with a distinct point of view about how a person, here a male teen, ought to comport themselves. It’s simulation as rehearsal, hence the repetition. For example, “touching” (groping) people or making a droolingly horny facial expression are offered as options but are always incorrect choices, inputs that are either quietly discarded or lead to a failstate or are openly chastised.

Walking its line gets stranger the further in you go, as it bends to fit the needs of a contrived plot. You get into a stupid dispute with Miho where neither You nor her are actually at fault, but you’re angry with her and she’s contrite, and the difficulty is that you actually aren’t offered the option to be upfront and forthright, or forgiving and ready to move on. The ultimate solution to how to patch up your relationship instead begins with making Miho start to cry. Then You insult her and act outraged, maximally seething, and only this course of action leads her to ask for your forgiveness and say she can’t bear the thought of never seeing You again. Through this route, she actually ends up saying the exact same lines verbatim which typically precede a game over, except this time You actually get to keep talking for no clear reason, and then You have to ask her “don’t you understand how I feel” while, importantly, not using any of the facial expressions that would actually indicate any feeling. What we are meant to glean about how to treat people from this hash is unclear at best and bad at worst.

It just seems like the game has a particular dramatic confrontation in mind and warps around it, in actually a pretty familiar and normal way to anyone who’s seen a kinda-lousy story where characters have no good reasons to be mad at each other, but the writers feel some kind of pressing need to gin up conflict from thin air as story grist, whilst also being too precious to actually have something go seriously awry. It’s a classic move of what I would say is just flat out classic bad storytelling, though there are many ways to recover from and redeem or forgive the beat, such as: making the irrationality part of the point, or giving some kind of reason for prolonged misunderstanding as in a farce, or just moving past the beat quickly enough that the audience doesn’t have time to get irritated and nit-picky about it. What Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School does instead is really dwell on it, and encourage the audience to deeply consider the emotions and logic of the scene, which seem more and more emotionally incoherent the longer the player goes over it. Instead of having the shape of the story and the things the player does in it determined by the formal structures of the game, they’ve gone and mounted a conventional story beat onto the adventure game trial-and-error framework which stretches it out until it rips apart.

This rehearsal dynamic is most easily navigated and clearly made apparent the first time the player has any effective choices at all, when they have their first substantial dialogue exchange with Mizuho/Miho, having just figured out the double-act. You get a bunch of A/B choices of what to say, and the choice is typically whether or not to talk about Miho’s celebrity status. Throughout the whole game, Miho gets really touchy and visibly angry if You ever bring up her job, and if you persist you head right to a game over. (In a shocking generosity for the era, this game has you start scenes over if you fail instead of the entire game.) The message is clear and agreeable: if you happen to meet a celeb in the flesh, just treat them like a normal person, don’t geek out.

However, this means the game exists in a sustained state of self-denial. The whole reason we are here, in and out of fiction, is that we are interested in Nakayama Miho due to her celebrity. But we must constantly dance around the subject, never addressing the facts head-on except when the game takes over for us. In fact, we are actively confronted with the possibility of speaking honestly and then quite deliberately suppressing it. The A/B choices demand to be read not as opposing pairs but in superposition and synthesis, as running commentary on one another, the polite conscious and the basal unconscious, each simultaneously possible and possibly simultaneous. This is the split personality of Miho/Mizuho, mechanized.

There’s actually a lot more significant pairs in the cast. The rich snob girl, Erika, and the rich snob boy, Masaomi. The strict vice principal, and the cuddly principal. The trio of Erika’s sycophants, and the trio of adult male thugs who work for Erika. There’s another character, Sadakichi, who’s your Mizuho — your shadow. Especially in the early game, he tags along making observations that your character cannot because your character is meant to be You, and You don’t know the kids at this new school. He has the same fannish predilections as You, but he is not as lucky, always a moment too late, so that You get to the plot first. His chubby looks are an object of ridicule from the first lines of the game, which marks him out permanently as someone who does not get to participate in romance or desire. Besides that, the game seems reasonably endeared of him. He gets a cool motorcycle! Sadakichi is at once a model of the ideal consumer audience and stigmatized.

Sex is also pointedly repressed and denied. It’s broached twice in the first act. Once, You run into the vice principal, an absolute tightwad, who gets embarrassed when You discover him carrying a porno mag around in his vest. It’s a natural tidy irony: the guy droning on and on about propriety and procedure is just poorly suppressing his own sleaziness and trying to do extend that same censorious attitude to everyone else. Secondly, and earlier, right before Your very first spoken exchange with Miho, while You’re just looking for the girl who dropped something when You bumped into her, Sadakichi hears some girls in a classroom and thinks that might be who you’re looking for. So, You peek in, and surprise: it’s two teen girls in their underwear getting dressed in a classroom after school for some reason! Miho shows up immediately after this shot for the second time, the first where You actually get to conversate with her at all.

This is… less natural and tidy. It’s a PG-13 riff on a gag I’d more expect in a bawdy college sex comedy of this era than the achingly chaste soap-operatic high school rom com this game otherwise is. It’s not entirely clear to me why it’s here, so pardon me while I overthink one ultimately insignificant shot while not even mentioning entire characters and subplots. It’s a wide shot with big bugged-out eyes, clearly more comically awkward than gratuitously titillating, but it’s not particularly funny because there’s no development of the premise towards any kind of point at all. Because it’s an honest accident around an inexplicable situation, it doesn’t really reflect on anyone’s decisions and thus doesn’t, say, characterize either Sadakichi or the player character as a bit of a sleaze. Because it’s so unpredictable, maybe it’s meant to juice the rest of the game with a certain charge; if not an erotic one, then one where any random thing could be around the next blind corner. Maybe it’s there because a frazzled attitude around sex is part of being 17. The language of cinematic montage connects this image directly with the appearance of Miho. This can either be interpreted 1) as supplementary — “for all their gentlemanly behavior, boys only have one thing on their mind when it comes to cute girls,” that though this is an accident it still formally commentates on the boys’ goals or unconscious desires, like the A/B choices — or 2) as contrast — this is not a game where you will be seeing Miho in her underwear, that’s for certain: not only is she a real-life 17-year-old celebrity, but by immediately following something a little prurient with polite navigation of choppy conversational waters you can argue it’s signalling to the audience that this story isn’t THAT, it’s THIS. Indeed, your relations with her are to be so very chaste that You don’t even get to successfully kiss before the end of the game.

Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School is often-enough cited as the first proper dating sim: The meat of the gameplay revolves around navigating dialog trees, and though that sounds pedestrian enough now, this is actually the first we’re seeing of it on this blog, though it’s not a new thing in 1987 Japan, and the ultimate goal of navigating these dialog trees is to master interpersonal social behavior such that You can successfully secure and perform dates with a virtual girl whose emotional state is tracked and displayed in some detail. I’m not a subject matter expert so I won’t make that genre call for myself, and besides, it’s not as though they sat down to make a dating sim because that concept didn’t exist yet so it could hardly inform its shape. Its clearest historical influence is once again from the Portopia Serial Murder Case [1983/1985] lineage. Portopia even has phone calls to gate progression!

However, there is another lineage of Japanese computer adventure games, the one I already mentioned back in that article: the pornos. An accidental-peeping-Tom scene would have a pretty obvious reason to be in one of those, maybe that’s what’s being expressly denied. History happened over there too, porn games didn’t sit still for 4 years either, and as best as I can tell they beat this game to the punch on the whole dialog-tree-navigation gameplay by about a year or two in titles like Kudokikata Oshiemasu [1986]. It’s not certain, but it’s certainly not impossible that that’s where the designers lifted the concept from: Sakaguchi and Square as a whole got their start in the computer adventure-gaming market, with their last computer game before working on consoles, Alpha [1986], having some softcore erotic elements. Perhaps Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School brings up and denies pornography as an allusion, a head nod, but that’s a pretty strong and spicy claim to be backed up by no evidence whatsoever, so let’s just call it a rhyme. Regardless, the dating sim and the porn game would remain strongly associated into the future, giving even chaste rom-coms like these a whiff of dirty and disreputable salaciousness that dogs the genre to this day.

-----

Originally posted on my blog, [https://arcadeidea.wordpress.com/2022/06/27/nakayama-miho-no-tokimeki-high-school-1987/](Arcade Idea.)