ludzu

517 Reviews liked by ludzu

Shadow President

1993

The Silver Case

2016

This review contains spoilers

In a game, let alone continuity, lousy with sharp, confrontational artistic direction, it’s one as simple as the back of the box that continues to work its way through me. It’s the illustration of Kusabi, Sakura, and Kosaka, in particular - Sakura’s exaggerated frown extends out of the image towards you while Kusabi and Kosaka converse around her. If you’ve played the game, you’re aware that this configuration can only happen in the events proceeding the finale (a massive torpedo-spoiler on the back of the box, funny!). By extension, this also means that the illustration is, to whatever degree, a reflection on the status quo after case#5:lifecut, i.e. the chapter of the game where everything boils over, a majority of the Transmitter cast straight up dies, and radical actions by the hands of the remaining cast occur.

I love this illustration for a few reasons - for one, Takashi Miyamoto captures a sense of mundanity so well. In game, you’re never really able to bear witness to a Kusabi at peace in ordinary life, and here he’s beautifully human in his pose - well-earned after his arc through the game. Secondly, through that same focus on the mundane lies a commentary on the dynamics these characters are engaged in. I don’t think it’s much of a stretch to imply that the gender dynamics put forth here can be seen as a disappointing reminder that leaving Kusabi (love ‘em as I do) as the sole surviving veteran of the HCU means that the same bitterness which ostracized Hachisuka, possibly enabling something within to give in to her inevitable death-filing and appearance as Ayame, is likely still in the air. But these observations pale, in my opinion, to the context.

As she continues ascending the 24th Ward’s crime department, after bearing witness to the very operation that almost(/successfully?) doomed her and the player character to a life of artificial personhood, and after witnessing the takedown of the two major antagonists of the game, Nezu and (eventually) Uminosuke, she still frowns at us, the player. Why? I thought danwa was a happy ending.

-

TSC is one of few games I can think of that really eludes simple genre description. Sure, it’s a crime procedural, up until it isn’t. It’s a conspiracy thriller... in spots. It’s Lynchian surrealist dystopia? Alright we’re just gonna say words now, I guess? The only thing that comes to mind for descriptors is, like, slipstream fiction, which, given 25W references seminal proto-Cyberpunk novella The Girl Who Was Plugged In, seems apt enough to settle on. I won’t even evoke the P-word. The one that rhymes with “toast auburn.”

But really, this thought exercise is all just a veiled move to get you to wonder about the limitation of genre fiction as it applies to TSC, and poke at its aspirations. For this to be a standard crime procedural, you’d expect the HCU to... function in some capacity? And conspiracy thriller’s a no-go considering the weight that spirituality and all other intangibles have here, in my opinion. The way I’ll continue from this point to put it is thus: the Mikumo 77 incident, the murder of Kamui by the underworld factions, and the ensuing Shelter Kids policy reverberate through the story on many different frequencies, and the effect of it all is so bleak that only genre convention can make the discussion palatable as fiction. But it doesn’t always cover it: the melancholic, ambling work of Tokio through Placebo, the brain-swelling conflict of information in Transmitter, I think both serve as a reminder that there’s no easy out from underneath the sin of government control. It’s no surprise, I guess, that the symptoms get much, much worse when we return to Kanto in The 25th Ward.

-

Kamuidrome thru danwa (and the equivalent reports from Placebo’s end) are so dizzying and hard to come to terms with that I have literally shaved my head since first playing this game. This is actually true! I have death-filed!

That said, I feel like an essential piece of advice I could give someone who’s in for their first time is to enact judgment on the information based on who and when it’s coming from. This is easy enough in some cases - I think most people are primed from birth to hate pedo-fascist Nakategawa enough to not mind his words. But even fan-favorite Kusabi, for instance... this entire game is a slow fade-to-white for him as he unlearns an entire ideology of criminality equating plague, one he’s enforced so much with violence, not just as a cop, but as a particularly fucked up cop. In the beginning, I wouldn’t blame you for sticking with the competent elder authority of the cast, but if the ending moments of Parade don’t convince you to question the prior chapters, then I don’t know what will. The state of this world can be figured out with relative certainty as long as you keep track of where you are in the game’s web.

Though deeply confusing (& not helped by a localization that I can only describe as “challenging” (no shade to Grasshopper James btw, I can only imagine trying to piece this together 😭)), this game masterfully tiers up its information in a way that makes the trek through the underbelly of the 24th Ward feel so uniquely haunting. While certain aspects (the bench-warming faction war at the batting center comes to mind) do feel a bit bizarre and maybe even underdeveloped as words on a (cyber)page, the thematic tapestry of this game is exceptionally rich, even among other lauded-for-thematic-richness games. I’m a lifelong MGS fan and even I have to admit that after coming to conclusions confident enough to type words about, I think we might be seeing a lunch-eating of unseen proportions.

I love this illustration for a few reasons - for one, Takashi Miyamoto captures a sense of mundanity so well. In game, you’re never really able to bear witness to a Kusabi at peace in ordinary life, and here he’s beautifully human in his pose - well-earned after his arc through the game. Secondly, through that same focus on the mundane lies a commentary on the dynamics these characters are engaged in. I don’t think it’s much of a stretch to imply that the gender dynamics put forth here can be seen as a disappointing reminder that leaving Kusabi (love ‘em as I do) as the sole surviving veteran of the HCU means that the same bitterness which ostracized Hachisuka, possibly enabling something within to give in to her inevitable death-filing and appearance as Ayame, is likely still in the air. But these observations pale, in my opinion, to the context.

As she continues ascending the 24th Ward’s crime department, after bearing witness to the very operation that almost(/successfully?) doomed her and the player character to a life of artificial personhood, and after witnessing the takedown of the two major antagonists of the game, Nezu and (eventually) Uminosuke, she still frowns at us, the player. Why? I thought danwa was a happy ending.

-

TSC is one of few games I can think of that really eludes simple genre description. Sure, it’s a crime procedural, up until it isn’t. It’s a conspiracy thriller... in spots. It’s Lynchian surrealist dystopia? Alright we’re just gonna say words now, I guess? The only thing that comes to mind for descriptors is, like, slipstream fiction, which, given 25W references seminal proto-Cyberpunk novella The Girl Who Was Plugged In, seems apt enough to settle on. I won’t even evoke the P-word. The one that rhymes with “toast auburn.”

But really, this thought exercise is all just a veiled move to get you to wonder about the limitation of genre fiction as it applies to TSC, and poke at its aspirations. For this to be a standard crime procedural, you’d expect the HCU to... function in some capacity? And conspiracy thriller’s a no-go considering the weight that spirituality and all other intangibles have here, in my opinion. The way I’ll continue from this point to put it is thus: the Mikumo 77 incident, the murder of Kamui by the underworld factions, and the ensuing Shelter Kids policy reverberate through the story on many different frequencies, and the effect of it all is so bleak that only genre convention can make the discussion palatable as fiction. But it doesn’t always cover it: the melancholic, ambling work of Tokio through Placebo, the brain-swelling conflict of information in Transmitter, I think both serve as a reminder that there’s no easy out from underneath the sin of government control. It’s no surprise, I guess, that the symptoms get much, much worse when we return to Kanto in The 25th Ward.

-

Kamuidrome thru danwa (and the equivalent reports from Placebo’s end) are so dizzying and hard to come to terms with that I have literally shaved my head since first playing this game. This is actually true! I have death-filed!

That said, I feel like an essential piece of advice I could give someone who’s in for their first time is to enact judgment on the information based on who and when it’s coming from. This is easy enough in some cases - I think most people are primed from birth to hate pedo-fascist Nakategawa enough to not mind his words. But even fan-favorite Kusabi, for instance... this entire game is a slow fade-to-white for him as he unlearns an entire ideology of criminality equating plague, one he’s enforced so much with violence, not just as a cop, but as a particularly fucked up cop. In the beginning, I wouldn’t blame you for sticking with the competent elder authority of the cast, but if the ending moments of Parade don’t convince you to question the prior chapters, then I don’t know what will. The state of this world can be figured out with relative certainty as long as you keep track of where you are in the game’s web.

Though deeply confusing (& not helped by a localization that I can only describe as “challenging” (no shade to Grasshopper James btw, I can only imagine trying to piece this together 😭)), this game masterfully tiers up its information in a way that makes the trek through the underbelly of the 24th Ward feel so uniquely haunting. While certain aspects (the bench-warming faction war at the batting center comes to mind) do feel a bit bizarre and maybe even underdeveloped as words on a (cyber)page, the thematic tapestry of this game is exceptionally rich, even among other lauded-for-thematic-richness games. I’m a lifelong MGS fan and even I have to admit that after coming to conclusions confident enough to type words about, I think we might be seeing a lunch-eating of unseen proportions.

Magic: The Gathering

1997

been playing hella yugioh and moved back 2 my parents place which might indicate illness & questionable judgment 2 some (🧍♂️) but confident in saying this is juiced. played this with a 2016 mod or smthn similar that added in cards up until then & just went absolutely 2 town with some green/white creature spam. just gets that i like being teased a lil with some perfunctory side quests and random encounters until i can go in the shop & get that one absolutely busted card that'll take my deck from celtics shaq at the free throw line brick machine to the most consistent bomb after bomb pile u've seen since the obama administration. late 90s British pc gaming influence all over this tooooooo every piece of armor is grainy as fuck all the sorceresses & enchantress sprites are just recolored elviras every creature from beyond the grave has glowing red eyes. shit just closes itself automatically when u beat the game too no credits no nayfin this is just gaming at its finest man.

Hands of the Killer

2020

Dares to ask what video games might look like had we all gotten home computers in 1917. Much more substantial than the first one, with kind of a symphonic structure. The first section, the modern apartment building, had all the instinctive joy of pointless exploration that I remember experiencing the first time I played Deus Ex. The kitsch architectural substrata are themselves a kind of a pale, kitschy callback to something like Goblet Grotto, but it blossoms really nicely into a manic final sequence that reminds me of the experience of reading Une semaine de bonte in one sitting at 4am.

This review contains spoilers

My interactions with your mother are quite explicit.

Feels out of time: not just like a YouTube essay but like YouTube essays a decade ago, as if it were still shaking off the baby feathers of Mr. Plinkett and the Angry Video Game Nerd. Fundamentally wrongheaded assessment of design born of a desperate love of dichotomies. Thought it might be a joke when he mentioned Shadow of the Colossus. Earns half a star for bashing Final Fantasy XVI.

Feels out of time: not just like a YouTube essay but like YouTube essays a decade ago, as if it were still shaking off the baby feathers of Mr. Plinkett and the Angry Video Game Nerd. Fundamentally wrongheaded assessment of design born of a desperate love of dichotomies. Thought it might be a joke when he mentioned Shadow of the Colossus. Earns half a star for bashing Final Fantasy XVI.

i dunno, let's keep this quick. to say it's a bit clumsy is an understatement - and there are certainly aspects of the overall narrative i struggle with - but the depths of its sincerity won me over. i have no particular attachment to yakuza 7 either, and in fact i find much of that game to be very awkward, stilted, and grating so ultimately no one's more stunned than myself here.

when it's not luxuriating in this chilled-out ocean's twelve vibe which i loved, infinite wealth is written with far more intentionality and consideration than most entries in the series; while one might accuse of it of verging on threadbare or cloying for its strict emphasis on theme, i think the game trusts its audience to take some of the emotional leaps necessary to make the storytelling work. character writing for the leads and the party members has seen a dramatic improvement across the board. ichiban as usual brings a lot of levity to the table - thankfully none of it quite as irritating in the zany sense as 7 liked to employ - but kiryu's portions of the game are comparatively sobering. collecting memoirs has a weird psychological effect at times but the series has earned the right to do this by this point given how much of the kiryu saga can feel siloed or compartmentalized - in the same vein as gaiden, the game almost damns him for this, for never taking a chance to stop and reflect, for the consequences of his interminable martyr complex

that tendency to bury the past is only contrasted further by infinite wealth being maybe the most direct sequel the series has seen yet - the events of that game are still fresh in everyone's mind and sets the stage for the overarching conflict and everyone's investment in said conflict. it's a surprisingly natural extension of a lot of 7's themes, and i found it worked better for me this time. 7 often felt more gestural than anything else - to me it balanced far too much as this metaphorical (and literal) tearing down of the old ways, handling the introduction of a new protagonist, paying lipservice to series veterans and setting up parallels to the original ryu ga gotoku. infinite wealth to me feels more fully-formed, more confident; i think the team was able to use this title's unique hook and premise to really bring the most out of 7s promise of something new, and it could only have achieved it by taking the time to reflect on the past.

to this end: they made the game a JRPG this time, that counts for something. and not just a JRPG but one that feels as close to traditional RGG action as possible. some excellent systems this time with a lot of fascinating interplay and the level curve is fantastic. not necessary to sum up all the changes, you've seen them, but they really promote a lot of dynamic decision-making with respect to positioning and once you figure out how status effects can correlate with them you feel like your third eye's opening. very fond memories here of navigating around a crowd of enemies - some of whom have been put to sleep - and figuring out how best to maximize damage without waking anyone drowsy up. lots more strategy and enjoyment to be had here than pretty much anywhere in 7.

that said, i know RGG prides themselves on the statistics relating to players completing their titles, but they could really afford to take a few more risks with enemy waves in the main campaign. i felt like my most interesting encounters were usually street bosses or main story bosses, but the main campaign's filled with trash mobs. and i'm not saying every fight has to be some tactician's exercise - in fact i think that's the opposite of what people actually would enjoy - but i really wish the game took the time to play around even more with positioning. there are some exciting scenarios in the game that are too few and far in-between. stages that split up the party, encounters with unique mechanics...would really liked to have seen more in that vein.

some extra notes - would like to dig a bit deeper into the strengths of the narrative as well as some additional hangups but i can't be assed to write more

- honolulu's great, it gets probably a little too big for its own good but it's a real breath of fresh air for most of the game

- yamai is the best new character they've introduced in years

- dondoko island feels like a classic yakuza minigame in the best possible way, might even represent the apex of this kind of design. not obscenely grindy but just something casual and comfortable with enough layers to dig into without being overwheming and enough versatility to express yourself. shame you can't really say the same for sujimon!

- kiryu's party is disarmingly charming and they have some insanely good banter

- despite what some have said, i think this is a good follow-up to gaiden. it's not explicit about it but this is still very much a reckoning with kiryu's character and his mentality; it is every bit as concerned and preoccupied with the series mythos, the core ideas and conflicts driving a lot of installments

- honestly found the pacing to be on-par for the average RGG title if not better. i can concede that the dondoko island introduction was a bit too long but that is the most ground i can afford. if we can accept y5 into our hearts we can accept infinite wealth; IW makes y5 look deranged for its intrusiveness despite both titles occupying a similar length. if any of it registers as an actual problem, i think people would benefit from revisiting yakuza 7 to find it is almost exactly the same structurally if not worse

- IW is home to maybe the best needle drop in the medium

- played in japanese, like i usually do, so no real interest in commenting on the english dub since it's not real to me but i will say that what i listened to seemed like a bit of a step back from the dub quality in previous RGG games. yongyea isn't a convincing kiryu either and while i could be a bit more of a hater here all i will say is there is a STAGGERING whiplash involved in casting a guy like that as the lead in a game with themes like this. in a grouchier mood, i think it would genuinely be a bit difficult to look past this and it does leave me feeling sour, but ultimately the dub doesn't reflect my chosen means of engaging with the title and it never will

- what is difficult to look past is the game's DLC rollout, which arbitrarily gates higher difficulties, new game +, and a postgame dungeon. i acquired these through dubious means (which i highly recommend you also do) so i feel confident in saying they're really not at all worth the money unless you had a desire to spend more time in this world, but what a colossal and egregious failure to price it in this fashion. new game + specifically has tons of bizarre issues that make me believe a revision of some kind was necessary.

- you will not regret downloading this mod that removes the doors in dungeons

long story short, ryu ga gotoku's journey began in 2005 with a simple motif: to live is to not run away. so much of infinite wealth is about taking that notion to its furthest extent. it couldn't have possibly hit at a better time for me. at times it might be a classic case of this series biting off a bit more than it can chew for a sequel, but i don't think there's anything you can reliably point to that would make me think this is one step forwards, two steps back.

also awesome to have a game that posits that hawaii is filled with the fire monks from elden ring and then you have to travel to the resident evil 4 island to beat them up

when it's not luxuriating in this chilled-out ocean's twelve vibe which i loved, infinite wealth is written with far more intentionality and consideration than most entries in the series; while one might accuse of it of verging on threadbare or cloying for its strict emphasis on theme, i think the game trusts its audience to take some of the emotional leaps necessary to make the storytelling work. character writing for the leads and the party members has seen a dramatic improvement across the board. ichiban as usual brings a lot of levity to the table - thankfully none of it quite as irritating in the zany sense as 7 liked to employ - but kiryu's portions of the game are comparatively sobering. collecting memoirs has a weird psychological effect at times but the series has earned the right to do this by this point given how much of the kiryu saga can feel siloed or compartmentalized - in the same vein as gaiden, the game almost damns him for this, for never taking a chance to stop and reflect, for the consequences of his interminable martyr complex

that tendency to bury the past is only contrasted further by infinite wealth being maybe the most direct sequel the series has seen yet - the events of that game are still fresh in everyone's mind and sets the stage for the overarching conflict and everyone's investment in said conflict. it's a surprisingly natural extension of a lot of 7's themes, and i found it worked better for me this time. 7 often felt more gestural than anything else - to me it balanced far too much as this metaphorical (and literal) tearing down of the old ways, handling the introduction of a new protagonist, paying lipservice to series veterans and setting up parallels to the original ryu ga gotoku. infinite wealth to me feels more fully-formed, more confident; i think the team was able to use this title's unique hook and premise to really bring the most out of 7s promise of something new, and it could only have achieved it by taking the time to reflect on the past.

to this end: they made the game a JRPG this time, that counts for something. and not just a JRPG but one that feels as close to traditional RGG action as possible. some excellent systems this time with a lot of fascinating interplay and the level curve is fantastic. not necessary to sum up all the changes, you've seen them, but they really promote a lot of dynamic decision-making with respect to positioning and once you figure out how status effects can correlate with them you feel like your third eye's opening. very fond memories here of navigating around a crowd of enemies - some of whom have been put to sleep - and figuring out how best to maximize damage without waking anyone drowsy up. lots more strategy and enjoyment to be had here than pretty much anywhere in 7.

that said, i know RGG prides themselves on the statistics relating to players completing their titles, but they could really afford to take a few more risks with enemy waves in the main campaign. i felt like my most interesting encounters were usually street bosses or main story bosses, but the main campaign's filled with trash mobs. and i'm not saying every fight has to be some tactician's exercise - in fact i think that's the opposite of what people actually would enjoy - but i really wish the game took the time to play around even more with positioning. there are some exciting scenarios in the game that are too few and far in-between. stages that split up the party, encounters with unique mechanics...would really liked to have seen more in that vein.

some extra notes - would like to dig a bit deeper into the strengths of the narrative as well as some additional hangups but i can't be assed to write more

- honolulu's great, it gets probably a little too big for its own good but it's a real breath of fresh air for most of the game

- yamai is the best new character they've introduced in years

- dondoko island feels like a classic yakuza minigame in the best possible way, might even represent the apex of this kind of design. not obscenely grindy but just something casual and comfortable with enough layers to dig into without being overwheming and enough versatility to express yourself. shame you can't really say the same for sujimon!

- kiryu's party is disarmingly charming and they have some insanely good banter

- despite what some have said, i think this is a good follow-up to gaiden. it's not explicit about it but this is still very much a reckoning with kiryu's character and his mentality; it is every bit as concerned and preoccupied with the series mythos, the core ideas and conflicts driving a lot of installments

- honestly found the pacing to be on-par for the average RGG title if not better. i can concede that the dondoko island introduction was a bit too long but that is the most ground i can afford. if we can accept y5 into our hearts we can accept infinite wealth; IW makes y5 look deranged for its intrusiveness despite both titles occupying a similar length. if any of it registers as an actual problem, i think people would benefit from revisiting yakuza 7 to find it is almost exactly the same structurally if not worse

- IW is home to maybe the best needle drop in the medium

- played in japanese, like i usually do, so no real interest in commenting on the english dub since it's not real to me but i will say that what i listened to seemed like a bit of a step back from the dub quality in previous RGG games. yongyea isn't a convincing kiryu either and while i could be a bit more of a hater here all i will say is there is a STAGGERING whiplash involved in casting a guy like that as the lead in a game with themes like this. in a grouchier mood, i think it would genuinely be a bit difficult to look past this and it does leave me feeling sour, but ultimately the dub doesn't reflect my chosen means of engaging with the title and it never will

- what is difficult to look past is the game's DLC rollout, which arbitrarily gates higher difficulties, new game +, and a postgame dungeon. i acquired these through dubious means (which i highly recommend you also do) so i feel confident in saying they're really not at all worth the money unless you had a desire to spend more time in this world, but what a colossal and egregious failure to price it in this fashion. new game + specifically has tons of bizarre issues that make me believe a revision of some kind was necessary.

- you will not regret downloading this mod that removes the doors in dungeons

long story short, ryu ga gotoku's journey began in 2005 with a simple motif: to live is to not run away. so much of infinite wealth is about taking that notion to its furthest extent. it couldn't have possibly hit at a better time for me. at times it might be a classic case of this series biting off a bit more than it can chew for a sequel, but i don't think there's anything you can reliably point to that would make me think this is one step forwards, two steps back.

also awesome to have a game that posits that hawaii is filled with the fire monks from elden ring and then you have to travel to the resident evil 4 island to beat them up

Wanted: Dead

2023

Disregarding the clunky dialogue, the aimless exploration of any of its themes and lack of really anything to say about any of them or even the fact that Konami will only let this franchise be Silent Hill 2 forever now: the climax of this game is that a woman is talked down from the roof by the prospect of shopping. Come the fuck on.

Neyasnoe

2023

very first characters you run into are three dudes listening to an instrumental cloud rap beat talkin about "finding the light" and "money". this was how all you drainers sounded like to me back in 2016. the good (low fidelity, usage of vaporwave/cloud rap/house music, smoke button) works here more than the bad (a bludgeoning of an ending, "loneliness +1", a general briefness). some striking moments like goin on a elliptical bender in a coastal town & getting really nervous eating potato chips around girls. think the ennui ultimately misses the mark for me in a way that other games with similar experiences don't though--the mood feels so particular to a college-adjacent early 20s anxiety & somehow too abstract to strike a real nerve. the ending convo is going for the jugular on a certain type of person but it feels a lil tacky in how subdued the rest of the experience is. VtM:B still clears for climatic conversations with a taxi driver i fear. i liked it enough to be invested in sad3d's other works when they go on sale tho.

Garten of Banban 6

2023

Path of the Abyss

2023

Played through Asellus's story. I will return to other scenarios later so I don't get burnt out. I was interested in Asellus based on Miwa Shoda's work in Nights of Azure and reading her interviews and drafts on the work in The Essence of SaGa Frontier/The Complete of SaGa Frontier. While it doesn't delve much into the eroticism or sensuality that you'd find in Nights of Azure, the focus on much more of a subtly queer identity struggle makes sense for what's a more conventional JRPG coming of age narrative that's just a bit quietly subversive of the gendered dimensions that usually surround such stories. It's really funny to imagine Miwa Shoda writing the scene after White Rose stays behind in the Dark Labyrinth and Zozma interrogates Asellus on her internalised homophobia while in the next room over in Division 1, the FF7 team is cooking up the Honey Bee Inn.

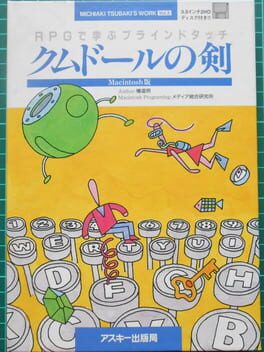

Kumdor no Ken

1991

The stuff dreams and nightmares are made of. Earthbound's cosmic horror climax sitting right next to Mavis Beacon touch-typing exercises. A critique and celebration of Dragon Quest not unlike Itoi's Mother series, just more spartan and deadpan. And it's finally translated in English, a privilege few PC-98 games enjoy even today (let alone most '90s East Asian PC software). Kumdor no Ken, or Sword of Kumdor, was creator Michiaki Tsubaki's most popular, well-regarded work during his short stint in games development, an edutainment staple for NEC and Mac computer labs. Many kids and young adults grew up with this, a story-driven word processing trainer for the JRPG age. Its story of exploring a strange land, overcoming bizarre obstacles, and indulging the frivolous but endearing people of this planet resonates with those same players today. Just imagine if Mario Teaches Typing had earned the kind of legacy and following a 16-bit Final Fantasy entry has now. Yet, until very recently, seemingly none in the West knew or cared about this.

| A typing tutor for all seasons |

Maybe I'm just built different, but Sword of Kumdor caught my attention several years ago while I was buzzing around decaying Japanese homepages and fan sites from the pre-Facebook days. It's almost pointillist visual style, learning to touch-type through turn-based combat, and bizarre sense of place and verisimilitude (or sekaikan) beguiled me. The closest Anglosphere equivalents to something this well-made, distinctive, and beloved across demographics are classics like Oregon Trail, or The Logical Journey of the Zoombinis. Whole petitions exist simply for reprints of the game for modern PCs, encased in the same unique book packaging ASCII & Tsubaki used back in 1991. Though my attempts to play through this adventure then were thwarted by the language barrier and poor keyboard skills, I could tell this was no mere fluke, forgery, or overhyped victim of nostalgia. Nothing on consoles, Western PCs, or the PC-98 and its competitors resembled Tsubaki's RPGs, almost all of which taught players about computing, typing, and other subject matter through idiosyncratic RPG stylings and structure. This was something special, and I had to know more. That's why [DISCLAIMER] I ended up being the beta tester on lynn's translation project, now having no excuse but to see this through.

Sword of Kumdor starts off unassuming, with barebones titles and a scrawly tutorial briefly going over controls. Using the F, J, and space keys to move forward, use the menu, and rotate your protagonist sounds weird and unintuitive, but comes naturally as you start the game in a galactic rest stop, waiting to board a rocket towards the titular world. Tsubaki describes our hero(ine) as a "Master of Blind Touch", a keyboard champion who's risen to the top but is bored, desperate for deeper understanding beyond their success on Earth. So we've traveled to a beleaguered, backwater planet calling for help, invaded by strange spellcasting monsters and sudden environmental disasters. It's not long before our own interplanetary trip to Kumdor goes awry, with the spacecraft malfunctioning and crash landing right into the starting town. With our keyboard keys and experience gone, no one recognizes us as the same touch-typing maestro promised to them. It's time to regain our equipment, master those typing skills once more, and figure out the cause of and solution to Kumdor's maladies!

As I've implied, most of the game loop involves exploring towns, overworlds, and dungeons, fighting random battles and collecting key items. This also entails the usual fiddling with inventory and managing your money, but Tsubaki challenges players to do something unique for a JRPG: play the whole game with touch-typing controls. I really cannot imagine how one would get through Sword of Kumdor on a gamepad, nor would it make any sense. From the most basic resting wrist fingerings to rapidly and precisely completing difficult sentences later on, this journey tries to make an avid typist out of anyone, even if its approach can get exhausting. One menu option brings you to a full keyboard HUD displaying your inputs, something I found necessary due to some PC-98 keys not natively mapping onto my US Windows layout. Another menu gives players a summary of their word-per-minute rating and trend over runtime, plus their WPM target which matters most at endgame. Teachers likely needed and asked for these tools the most, but anyone playing this to completion should find 'em useful too. I had to make a new .txt file in my Neko Project II emulator directory rebinding some keys to in-game equivalents, which made the virtual key-map important.

Forget years of button-mashing wearing out your gamepad—this game occasionally had me wondering if I'd finally feel some mushiness from my spacebar! (Not the case, thankfully, but then again my keyboard has faux Cherry Blue switches, designed to remain punchy.) I've long wondered if the Art Academy series could help me unlearn my chickenscratch handwriting and drawing, and parts of Sword of Kumdor did a lot to correct bad typing habits I've built over the ages. Everything centers around your muscle memory here, with slow and clumsy typing punished with Game Overs in combat and puzzles. Battles are all 1-on-1 affairs, as are "gates" which you unlock using the same system. Enemies shout prompts, you type them back as fast and accurate as you can, and this deals damage based on your EXP points total. Increasing max EXP requires visiting practice areas, usually within towns, which check if you've bought the right keys and then test you with them. Completing prompts fast with no errors leads to either an optional prompt at the end of fights—which reward the lion's share of an encounter's EXP as long as you don't mess up once—or a higher raise in max EXP during the aforementioned tests. These slight variations on the same repetitive exercises keeps most of the game feeling fresh despite what it demands from players.

| Old tales, new travails |

Another boon for us all is the Dragon Quest-like game progression, which involves finding and using movement items to proceed further. Though there's only one real "dungeon" stuck in the endgame, crossing each overworld section means talking to the right NPCs (which rarely feels tedious) to acquire the right stuff. For example, a mid-game fog valley barrier proves insurmountable until one locates the compass needed to navigate it. Diving into and out of lakes or ponds? Better snag a snorkel! And because there's no way to passively heal, Sword of Kumdor punishes players who forget to pack restoratives, either found throughout the realm or bought in towns. There's both consumable items with various properties and magic scrolls which only work if you have all the keys needed to type them. (Early on, you won't even have an Enter key with which to submit the spell name.) All this could easily be too simplistic or convoluted like in many contemporary JRPGs, but Tsubaki does a good job of balancing frequent typing with visiting new locations and people often.

If anything, Sword of Kumdor incentivizes its digital stenographers to chat up as many of the locals as possible. So much dialogue between villagers, scientists, and plot-critical individuals goes for light, often ironic or self-effacing conversation, the kind you'd expect from modern Earthbound-inspired xRPGs and adventure (ADV/VN) faire. Lake divers kvetch to you and one another about how the monsters plaguing their lake have left them with nothing good to do. Kumdor-ians complain endlessly about their inability to learn touch-typing and fight back, often resorting to increasingly absurd solutions. Hermits and dilapidated robots muse about the mysterious Dreampoint, which seems to be corrupted and responsible for the planet's septic response to its inhabitants. Sword of Kumdor starts you off as a detached observer of their foibles, humor, and resignation to what fate has in store for them. Only much later on do major NPCs recognize you as the purported "keyboard warrior" they asked for, and even then everybody's too busy trying to live, survive, and enjoy themselves to notice. Nothing in this pre-Mother 2 odyssey from 1991 ever gets as nakedly comical or referential as the usual suspects today, but all the signs are here from start to finish.

Most of an average playthrough (about 6-7 hours prior to endgame) goes by with little issue, intuitive and freshly paced as it is, up until endgame. Trudging through lava flows to reach safe land, or hopping across pits and solving gates, takes a bit more time, but that's far from the worst Tsubaki throws at you. It's the long-awaited final stretch, the Dreampoint, which turns Sword of Kumdor from an occasionally tricky edutainment JRPG into a brutal marathon of skill and carpal tunnel risks. The dungeon's gimmick? Find those warp points and save up enough dosh to buy the house they're hidden inside. While you can safely run from any battle elsewhere in the game, only suffering minor damage or easily healed status conditions if unlucky, most of the baddies patrolling this place can do terrifying things to players. Some render you invisible before curing, others saddle you with an unhealable darkness of vision (only fading if you can escape the Dreampoint), and a couple outright steal one or more keys if you run for it! My strategy evolved towards hoarding restoration food, saving very rare teleportation magic for emergencies, and then trying to brute-force through these oppressive mazy floors until I reached the next warp. Once I'd vanquished the "final boss", this conclusion felt more like the second half, taking as much time as events leading to it (if not more).

This difficulty and investment spike risks spurning players entirely. Indeed, I began to play less, making what progress I could in short sessions to avoid burnout. But it's also exactly the kind of grueling test that Tsubaki (and I presume his friends at ASCII Corp.) had in mind for budding touch-typists. What qualified as dungeons and side-areas before pales in comparison to this crawl, and I think it ultimately works out for the better. I'd reached just shy of 2000 EXP by the end, relying more on my typing skills than just pushing up numbers in the practice rooms when I could two-shot most enemies already. Previous emphasis on building muscle memory and character status gives way to the player themselves embodying their male or female avatar's struggle to save the world. Like the best finales in ye olde Phantasy Star or Ys saga of the era, strategy and self-pacing count more than grinding to a sure victory, and so the push-pull of tension and relief becomes so much stronger in turn. It recontextualizes most of the rest of the game as a cleverly-disguised series of quizzes and reviews, preparing us for this cram school's worth of battles, conundrums, and focused sprints to safety. And, being the masochist I am (not unlike '90s Japanese students here), I was hooked.

| Mysteries of the inner globe |

The Dreampoint itself summarizes many of the story's most interesting themes and oddities, a labyrinth of disfigured memories and boogeymen foreshadowing the big twist. So far, Sword of Kumdor has presented its planet as a microcosm of Showa-era Japan, with its polite but passive-aggressive populace and a strong bystander effect despite the unforeseen consequences of the planet's sentient core being invaded. Just like how the gravy train of real estate speculation and over-lending led to the bubble bursting not long before Tsubaki made this, Kumdor's palace royals and courtiers' fascination with the Dreampoint, a crossing point of everyone's conscious and subconscious thoughts, led to an ecological apocalypse of sorts. As a decorated yet anonymous outsider to these problems—the "Westerner" in the equation, not knowing local history, problems, etc.—it's just as problematic that we have to bail the leaders out of this predicament. Even as we help citizens and eventually the ultimate victim of the Dreampoint, what gratitude we receive comes mostly from observable touch-typing mastery. Think about whenever your boss or workplace values you most for results and business contributions, more so than just being, having that humanity and empathy we desire yet undervalue.

Beneath all the hijinks, calamities, and talking to sentient key-trees and key-fish lies a critical but optimistic set of messages for kids and adults in modern life. Through talent, determination, and side-stepping structural barriers whenever/wherever possible, one can recover from setbacks and prosper in ways previously unfathomed. By understanding one's environment and believing in your abilities—not taking things for granted or falling into impostor syndrome—you can convince the world around you of your worth, even if it shouldn't need such arguing. I appreciate what Tsubaki successfully communicates here even more because it does so without any hint of didacticism. Each ending, based on your endgame WPM target, reflects somewhat upon what comes after this arduous journey, be it the "bad" ending having Kumdor's king advocate for consuming oneself in fantasy (the book he wants to get back to instead of talking more with you), or the best ending having a couple of royals earnestly ask for you to tutor them in the touch-typing ways. Key NPCs only realize you're the Master of Blind Touch after your actions and progress prove that so, and the ancient non-Kumdorian inhabitants of the land, from wisened tree and fish folk to the mangled but salient denizens of the Dreampoint, comment on how far you've come without overselling the point. On the contrary, that "regular guy in the street" in Kumiel, the capital, doesn't pay players any mind, instead encouraging us to think about their relative privileges while other, more talkative folks escape volcanic eruptions or watch their jobs stagnate.

—————Ending spoilers below!—————

Something tells me Tsubaki was nonetheless reverent towards the principles of Yuji Horii's work on adventures like Portopia Serial Murder Case and, of course, the inescapable Dragon Quest franchise from '86 onward. Our protagonist's trip from wrecked ship to the neural nexus of this world both mirrors and reimagines Loto's quest in the original JRPG. Rather than starting in an open, hospitable castle with its jolly version of Lord British, we only reach the palace later on, just to be turned away because the real Master of Blind Touch would have solved everyone's problems already. Instead of a charismatic Dragonlord tempting players with a chance to join his side, the Dreampoint itself has parasitically merged with Mido, the prince of Kumdor whose own fears, flaws, and insecurities have bequeathed indescribable terrors upon the realm. Here the choice isn't whether or not to join evil, but to let yourself down at the bitter end, leaving this game's Loto to fester as a figurative child of Omelas.

Key moments in the original Dragon Quest's progression are rearranged, malformed, and presented to players no doubt familiar with JRPG cliches as something genuinely new. Bosses aren't cartoony Akira Toriyama drawings, but huge text prompts mixing in text from sources as wide as fairy tales (Snow White), journalism (a summary of '80s US-Japan relations and the Plaza Accord), and other unsettlingly real or familiar subject matter. Hotels go from quaint to multi-floor behemoths, medieval-garbed shopkeepers to lumpy blanks, and soundtracks from cheerful tunes to bright but ominous interludes. Even the biomes are now hostile: white fog traps you in a loop of encounters, water rapids destroy you underwater, and the undulating "void" of the Dreampoint's penultimate room can swallow you whole. In this messed-up but discernable reconfiguration of Dragon Quest-isms, much like the non sequiturs posed to players in something like Space Funeral, we're asked to rethink how much these tropes matter. After all, in a universe where the keyboard's mightier than the sword, what defines a hero's journey, the stakes in general, and how others perceive it all?

—————No more spoilers!—————

Shigesato Itoi often gets a truckload of credit in modern video games discourse for this kind of effortless, trenchant conveyance and literary game design. I think it's sobering to encounter other examples of such creators, working with their own restrictions and life stories, achieving much the same but to far less acclaim and/or recognition. Sword of Kumdor treats its participants with so much intelligence, no matter where you're from or which stage of your lifetime, that it can implicitly pass for an alternative-universe Mother series entry with such ease that I'm a little jealous. Here's exactly the kind of iterative yet unconventional trip through engaging systems, encounters, and heartwarming moments which I hoped existed somewhere in the Japanese PC games library, knowing its breadth and variety. Yes, this is far from a perfect game, what with its harsh dexterity requirements and cliff wall of an ending gauntlet. The audiovisuals, though very striking and identifiable, also play to the 16-color, high-resolution, FM-synthesized hardware in abrasive ways. Not everyone's gonna love eye-searing monsters, pulsing percussion-less and alien aural textures, or the Eisenstein-like use of strong colors to denote sleeping at inns or dying ingloriously in battle. But it all comes together to make something truly "PC-98" for me, a defining piece of entertainment which defies current assumptions about what one can and should expect.

| A sword for Kumdor, my axe for J-PC games scorned |

Years of Tumblr visual blogs, jokes about Sex 2, and the understandable but oft misleading characterization of the PC-98 as an erotic adventures platform makes Sword of Kumdor stand out that much more. It's definitely on the extreme, experimental end of the system's library, but quite the counter-example to explain how differently Japanese users perceived NEC's dominant PC up until Windows 95. True, otaku subcultures and reliable sales of horny soft to those audiences prevailed from the turn of the '90s to today, but the PC-98 catered to so many niche markets, like wargaming and fantasy JRPGs. Reductionist, convenient portrayals of this platform, both in and outside its original regions, downplay or even eliminate the chances that iconic games like Kumdor get the appreciation they deserve. And this isn't a close-and-shut case of Tsubaki's RPGs being the exception to the rule, as many other sims, ADVs, and RPGs didn't rely on any erotica to sell and stand out, ex. Yougekitai's occult detective premise or Tokio's satirical comedy of bubble-era economy and politics. It's a shame that the kind of enthusiast press and institutional promotion that all-ages games like Zoombinis gets in the US hasn't extended to Kumdor in its home country, working against all the fans' nostalgia and agitation to bring it back into the mainstream like it's the early '90s again.

For me, the critical burial and mere rumblings of relevance emanating in Sword of Kumdor's wake seems unjust. (Yes, I know life isn't fair and that these are just first-world problems, but gimme some slack here.) Writer, designer, and programmer Michiaki Tsubaki came from an outsider background in art design to iterate on the popular Dragon Quest mold in ways no one else accomplished. And it makes perfect sense he'd choose the PC-98, simultaneously a bastion for the business world and close-knit interest groups, to house these beguiling, often subversive adventures of learning. Yet so many out West (as well as in Japan, though much less so among uses/players from its heyday) can simply say "the PC-98 is for porn, or Touhou, or mahjong", etc. and leave it at that. I'm not going to say they're bad or wrong, given the large amount of eroge and "weird Japan" software you can find for the system, but Tsubaki didn't dabble in weirdness or exotica for its own sake, let alone fashion or vibes culture. His interactive media seeks to enthrall and unsettle people as much as help and inspire them, using these super-deformed, cute-yet-not elements and methods. In a sense, what he did with Kumdor, the INSIDERS duology, and Toki no Shirube adheres more to a traditional fully-fledged aesthetic than some superficial trend. And that's something I see with a general majority of PC-98 games, even some eroge ADVs.

In short, there's so much more to the PC-98 scene (and PC-88, and MSX, and…better stop here) in terms of daring, diverse, and dare I say important gaming experiences which Sword of Kumdor exemplifies. We can't settle for placing YU-NO or Rusty atop curated, canonical lists of the platform's greats and also overlook ambitious/art works like this, not unless all that matters is just ogling these games and their histories at a glance. (Again, I love quite a bit of eroge and better-known PC-X8 darlings, but they're not the end-all-be-all.) Tsubaki was just one talented bedroom-coding polymath among many in that milieu, pushing unwieldy hardware to its limits and daring players to keep up. Our unlikely Master of Blind Touch journeys from the end of one life into the beginnings of another, reassembling a broken world's hopes and dreams from above and within its core. That reconstructive mentality resonates with me, someone who's always willing to give these old, janky but often great PC games their due. You could find all kinds of ideas, stories, genre hybrids, different design paradigms, and truly unique fantasies and realities across East Asian PC games like this, complementing the console/arcade landscape with what those couldn't or didn't provide.

That said, it's not super easy for me to recommend this to anyone starting out with PC-98 emulation or using a real machine. I can think of very few notable games on the system which need this much keyboard configuration to feel all that great to play in long bouts. But it's still one of the most interesting xRPGs on the system—hell, in these genres' history! Not many stories can wield weirdness with purpose and the right amount of restraint like this. Not many edutainment titles dare their players to head into dangerous, troubling circumstances either. And not many are willing to risk players' attention and comfort for the sake of a tonally consistent, draining final act which wraps all loose ends, game loops, and story motifs into one. I have nothing but respect and admiration for Tsubaki's efforts here, and his lack of presence and biographical info even within Japan just saddens me. Regardless, I deem Sword of Kumdor the best way to get into this designer's catalog of bizarre yet relatable JRPGs, with the more computer science-based INSIDERS and Gaia-themed Stellar Sign comprising the rest of these PC-98 tomes. Of course, one might argue we're not getting the whole experience without translations of the dense hintbooks provided with each Tsubaki release, something ASCII Corporation did to help players and persuade educators to include the games in their curricula. But this first translation patch will definitely suffice!

| A typing tutor for all seasons |

Maybe I'm just built different, but Sword of Kumdor caught my attention several years ago while I was buzzing around decaying Japanese homepages and fan sites from the pre-Facebook days. It's almost pointillist visual style, learning to touch-type through turn-based combat, and bizarre sense of place and verisimilitude (or sekaikan) beguiled me. The closest Anglosphere equivalents to something this well-made, distinctive, and beloved across demographics are classics like Oregon Trail, or The Logical Journey of the Zoombinis. Whole petitions exist simply for reprints of the game for modern PCs, encased in the same unique book packaging ASCII & Tsubaki used back in 1991. Though my attempts to play through this adventure then were thwarted by the language barrier and poor keyboard skills, I could tell this was no mere fluke, forgery, or overhyped victim of nostalgia. Nothing on consoles, Western PCs, or the PC-98 and its competitors resembled Tsubaki's RPGs, almost all of which taught players about computing, typing, and other subject matter through idiosyncratic RPG stylings and structure. This was something special, and I had to know more. That's why [DISCLAIMER] I ended up being the beta tester on lynn's translation project, now having no excuse but to see this through.

Sword of Kumdor starts off unassuming, with barebones titles and a scrawly tutorial briefly going over controls. Using the F, J, and space keys to move forward, use the menu, and rotate your protagonist sounds weird and unintuitive, but comes naturally as you start the game in a galactic rest stop, waiting to board a rocket towards the titular world. Tsubaki describes our hero(ine) as a "Master of Blind Touch", a keyboard champion who's risen to the top but is bored, desperate for deeper understanding beyond their success on Earth. So we've traveled to a beleaguered, backwater planet calling for help, invaded by strange spellcasting monsters and sudden environmental disasters. It's not long before our own interplanetary trip to Kumdor goes awry, with the spacecraft malfunctioning and crash landing right into the starting town. With our keyboard keys and experience gone, no one recognizes us as the same touch-typing maestro promised to them. It's time to regain our equipment, master those typing skills once more, and figure out the cause of and solution to Kumdor's maladies!

As I've implied, most of the game loop involves exploring towns, overworlds, and dungeons, fighting random battles and collecting key items. This also entails the usual fiddling with inventory and managing your money, but Tsubaki challenges players to do something unique for a JRPG: play the whole game with touch-typing controls. I really cannot imagine how one would get through Sword of Kumdor on a gamepad, nor would it make any sense. From the most basic resting wrist fingerings to rapidly and precisely completing difficult sentences later on, this journey tries to make an avid typist out of anyone, even if its approach can get exhausting. One menu option brings you to a full keyboard HUD displaying your inputs, something I found necessary due to some PC-98 keys not natively mapping onto my US Windows layout. Another menu gives players a summary of their word-per-minute rating and trend over runtime, plus their WPM target which matters most at endgame. Teachers likely needed and asked for these tools the most, but anyone playing this to completion should find 'em useful too. I had to make a new .txt file in my Neko Project II emulator directory rebinding some keys to in-game equivalents, which made the virtual key-map important.

Forget years of button-mashing wearing out your gamepad—this game occasionally had me wondering if I'd finally feel some mushiness from my spacebar! (Not the case, thankfully, but then again my keyboard has faux Cherry Blue switches, designed to remain punchy.) I've long wondered if the Art Academy series could help me unlearn my chickenscratch handwriting and drawing, and parts of Sword of Kumdor did a lot to correct bad typing habits I've built over the ages. Everything centers around your muscle memory here, with slow and clumsy typing punished with Game Overs in combat and puzzles. Battles are all 1-on-1 affairs, as are "gates" which you unlock using the same system. Enemies shout prompts, you type them back as fast and accurate as you can, and this deals damage based on your EXP points total. Increasing max EXP requires visiting practice areas, usually within towns, which check if you've bought the right keys and then test you with them. Completing prompts fast with no errors leads to either an optional prompt at the end of fights—which reward the lion's share of an encounter's EXP as long as you don't mess up once—or a higher raise in max EXP during the aforementioned tests. These slight variations on the same repetitive exercises keeps most of the game feeling fresh despite what it demands from players.

| Old tales, new travails |

Another boon for us all is the Dragon Quest-like game progression, which involves finding and using movement items to proceed further. Though there's only one real "dungeon" stuck in the endgame, crossing each overworld section means talking to the right NPCs (which rarely feels tedious) to acquire the right stuff. For example, a mid-game fog valley barrier proves insurmountable until one locates the compass needed to navigate it. Diving into and out of lakes or ponds? Better snag a snorkel! And because there's no way to passively heal, Sword of Kumdor punishes players who forget to pack restoratives, either found throughout the realm or bought in towns. There's both consumable items with various properties and magic scrolls which only work if you have all the keys needed to type them. (Early on, you won't even have an Enter key with which to submit the spell name.) All this could easily be too simplistic or convoluted like in many contemporary JRPGs, but Tsubaki does a good job of balancing frequent typing with visiting new locations and people often.

If anything, Sword of Kumdor incentivizes its digital stenographers to chat up as many of the locals as possible. So much dialogue between villagers, scientists, and plot-critical individuals goes for light, often ironic or self-effacing conversation, the kind you'd expect from modern Earthbound-inspired xRPGs and adventure (ADV/VN) faire. Lake divers kvetch to you and one another about how the monsters plaguing their lake have left them with nothing good to do. Kumdor-ians complain endlessly about their inability to learn touch-typing and fight back, often resorting to increasingly absurd solutions. Hermits and dilapidated robots muse about the mysterious Dreampoint, which seems to be corrupted and responsible for the planet's septic response to its inhabitants. Sword of Kumdor starts you off as a detached observer of their foibles, humor, and resignation to what fate has in store for them. Only much later on do major NPCs recognize you as the purported "keyboard warrior" they asked for, and even then everybody's too busy trying to live, survive, and enjoy themselves to notice. Nothing in this pre-Mother 2 odyssey from 1991 ever gets as nakedly comical or referential as the usual suspects today, but all the signs are here from start to finish.

Most of an average playthrough (about 6-7 hours prior to endgame) goes by with little issue, intuitive and freshly paced as it is, up until endgame. Trudging through lava flows to reach safe land, or hopping across pits and solving gates, takes a bit more time, but that's far from the worst Tsubaki throws at you. It's the long-awaited final stretch, the Dreampoint, which turns Sword of Kumdor from an occasionally tricky edutainment JRPG into a brutal marathon of skill and carpal tunnel risks. The dungeon's gimmick? Find those warp points and save up enough dosh to buy the house they're hidden inside. While you can safely run from any battle elsewhere in the game, only suffering minor damage or easily healed status conditions if unlucky, most of the baddies patrolling this place can do terrifying things to players. Some render you invisible before curing, others saddle you with an unhealable darkness of vision (only fading if you can escape the Dreampoint), and a couple outright steal one or more keys if you run for it! My strategy evolved towards hoarding restoration food, saving very rare teleportation magic for emergencies, and then trying to brute-force through these oppressive mazy floors until I reached the next warp. Once I'd vanquished the "final boss", this conclusion felt more like the second half, taking as much time as events leading to it (if not more).

This difficulty and investment spike risks spurning players entirely. Indeed, I began to play less, making what progress I could in short sessions to avoid burnout. But it's also exactly the kind of grueling test that Tsubaki (and I presume his friends at ASCII Corp.) had in mind for budding touch-typists. What qualified as dungeons and side-areas before pales in comparison to this crawl, and I think it ultimately works out for the better. I'd reached just shy of 2000 EXP by the end, relying more on my typing skills than just pushing up numbers in the practice rooms when I could two-shot most enemies already. Previous emphasis on building muscle memory and character status gives way to the player themselves embodying their male or female avatar's struggle to save the world. Like the best finales in ye olde Phantasy Star or Ys saga of the era, strategy and self-pacing count more than grinding to a sure victory, and so the push-pull of tension and relief becomes so much stronger in turn. It recontextualizes most of the rest of the game as a cleverly-disguised series of quizzes and reviews, preparing us for this cram school's worth of battles, conundrums, and focused sprints to safety. And, being the masochist I am (not unlike '90s Japanese students here), I was hooked.

| Mysteries of the inner globe |

The Dreampoint itself summarizes many of the story's most interesting themes and oddities, a labyrinth of disfigured memories and boogeymen foreshadowing the big twist. So far, Sword of Kumdor has presented its planet as a microcosm of Showa-era Japan, with its polite but passive-aggressive populace and a strong bystander effect despite the unforeseen consequences of the planet's sentient core being invaded. Just like how the gravy train of real estate speculation and over-lending led to the bubble bursting not long before Tsubaki made this, Kumdor's palace royals and courtiers' fascination with the Dreampoint, a crossing point of everyone's conscious and subconscious thoughts, led to an ecological apocalypse of sorts. As a decorated yet anonymous outsider to these problems—the "Westerner" in the equation, not knowing local history, problems, etc.—it's just as problematic that we have to bail the leaders out of this predicament. Even as we help citizens and eventually the ultimate victim of the Dreampoint, what gratitude we receive comes mostly from observable touch-typing mastery. Think about whenever your boss or workplace values you most for results and business contributions, more so than just being, having that humanity and empathy we desire yet undervalue.

Beneath all the hijinks, calamities, and talking to sentient key-trees and key-fish lies a critical but optimistic set of messages for kids and adults in modern life. Through talent, determination, and side-stepping structural barriers whenever/wherever possible, one can recover from setbacks and prosper in ways previously unfathomed. By understanding one's environment and believing in your abilities—not taking things for granted or falling into impostor syndrome—you can convince the world around you of your worth, even if it shouldn't need such arguing. I appreciate what Tsubaki successfully communicates here even more because it does so without any hint of didacticism. Each ending, based on your endgame WPM target, reflects somewhat upon what comes after this arduous journey, be it the "bad" ending having Kumdor's king advocate for consuming oneself in fantasy (the book he wants to get back to instead of talking more with you), or the best ending having a couple of royals earnestly ask for you to tutor them in the touch-typing ways. Key NPCs only realize you're the Master of Blind Touch after your actions and progress prove that so, and the ancient non-Kumdorian inhabitants of the land, from wisened tree and fish folk to the mangled but salient denizens of the Dreampoint, comment on how far you've come without overselling the point. On the contrary, that "regular guy in the street" in Kumiel, the capital, doesn't pay players any mind, instead encouraging us to think about their relative privileges while other, more talkative folks escape volcanic eruptions or watch their jobs stagnate.

—————Ending spoilers below!—————

Something tells me Tsubaki was nonetheless reverent towards the principles of Yuji Horii's work on adventures like Portopia Serial Murder Case and, of course, the inescapable Dragon Quest franchise from '86 onward. Our protagonist's trip from wrecked ship to the neural nexus of this world both mirrors and reimagines Loto's quest in the original JRPG. Rather than starting in an open, hospitable castle with its jolly version of Lord British, we only reach the palace later on, just to be turned away because the real Master of Blind Touch would have solved everyone's problems already. Instead of a charismatic Dragonlord tempting players with a chance to join his side, the Dreampoint itself has parasitically merged with Mido, the prince of Kumdor whose own fears, flaws, and insecurities have bequeathed indescribable terrors upon the realm. Here the choice isn't whether or not to join evil, but to let yourself down at the bitter end, leaving this game's Loto to fester as a figurative child of Omelas.

Key moments in the original Dragon Quest's progression are rearranged, malformed, and presented to players no doubt familiar with JRPG cliches as something genuinely new. Bosses aren't cartoony Akira Toriyama drawings, but huge text prompts mixing in text from sources as wide as fairy tales (Snow White), journalism (a summary of '80s US-Japan relations and the Plaza Accord), and other unsettlingly real or familiar subject matter. Hotels go from quaint to multi-floor behemoths, medieval-garbed shopkeepers to lumpy blanks, and soundtracks from cheerful tunes to bright but ominous interludes. Even the biomes are now hostile: white fog traps you in a loop of encounters, water rapids destroy you underwater, and the undulating "void" of the Dreampoint's penultimate room can swallow you whole. In this messed-up but discernable reconfiguration of Dragon Quest-isms, much like the non sequiturs posed to players in something like Space Funeral, we're asked to rethink how much these tropes matter. After all, in a universe where the keyboard's mightier than the sword, what defines a hero's journey, the stakes in general, and how others perceive it all?

—————No more spoilers!—————

Shigesato Itoi often gets a truckload of credit in modern video games discourse for this kind of effortless, trenchant conveyance and literary game design. I think it's sobering to encounter other examples of such creators, working with their own restrictions and life stories, achieving much the same but to far less acclaim and/or recognition. Sword of Kumdor treats its participants with so much intelligence, no matter where you're from or which stage of your lifetime, that it can implicitly pass for an alternative-universe Mother series entry with such ease that I'm a little jealous. Here's exactly the kind of iterative yet unconventional trip through engaging systems, encounters, and heartwarming moments which I hoped existed somewhere in the Japanese PC games library, knowing its breadth and variety. Yes, this is far from a perfect game, what with its harsh dexterity requirements and cliff wall of an ending gauntlet. The audiovisuals, though very striking and identifiable, also play to the 16-color, high-resolution, FM-synthesized hardware in abrasive ways. Not everyone's gonna love eye-searing monsters, pulsing percussion-less and alien aural textures, or the Eisenstein-like use of strong colors to denote sleeping at inns or dying ingloriously in battle. But it all comes together to make something truly "PC-98" for me, a defining piece of entertainment which defies current assumptions about what one can and should expect.

| A sword for Kumdor, my axe for J-PC games scorned |

Years of Tumblr visual blogs, jokes about Sex 2, and the understandable but oft misleading characterization of the PC-98 as an erotic adventures platform makes Sword of Kumdor stand out that much more. It's definitely on the extreme, experimental end of the system's library, but quite the counter-example to explain how differently Japanese users perceived NEC's dominant PC up until Windows 95. True, otaku subcultures and reliable sales of horny soft to those audiences prevailed from the turn of the '90s to today, but the PC-98 catered to so many niche markets, like wargaming and fantasy JRPGs. Reductionist, convenient portrayals of this platform, both in and outside its original regions, downplay or even eliminate the chances that iconic games like Kumdor get the appreciation they deserve. And this isn't a close-and-shut case of Tsubaki's RPGs being the exception to the rule, as many other sims, ADVs, and RPGs didn't rely on any erotica to sell and stand out, ex. Yougekitai's occult detective premise or Tokio's satirical comedy of bubble-era economy and politics. It's a shame that the kind of enthusiast press and institutional promotion that all-ages games like Zoombinis gets in the US hasn't extended to Kumdor in its home country, working against all the fans' nostalgia and agitation to bring it back into the mainstream like it's the early '90s again.

For me, the critical burial and mere rumblings of relevance emanating in Sword of Kumdor's wake seems unjust. (Yes, I know life isn't fair and that these are just first-world problems, but gimme some slack here.) Writer, designer, and programmer Michiaki Tsubaki came from an outsider background in art design to iterate on the popular Dragon Quest mold in ways no one else accomplished. And it makes perfect sense he'd choose the PC-98, simultaneously a bastion for the business world and close-knit interest groups, to house these beguiling, often subversive adventures of learning. Yet so many out West (as well as in Japan, though much less so among uses/players from its heyday) can simply say "the PC-98 is for porn, or Touhou, or mahjong", etc. and leave it at that. I'm not going to say they're bad or wrong, given the large amount of eroge and "weird Japan" software you can find for the system, but Tsubaki didn't dabble in weirdness or exotica for its own sake, let alone fashion or vibes culture. His interactive media seeks to enthrall and unsettle people as much as help and inspire them, using these super-deformed, cute-yet-not elements and methods. In a sense, what he did with Kumdor, the INSIDERS duology, and Toki no Shirube adheres more to a traditional fully-fledged aesthetic than some superficial trend. And that's something I see with a general majority of PC-98 games, even some eroge ADVs.

In short, there's so much more to the PC-98 scene (and PC-88, and MSX, and…better stop here) in terms of daring, diverse, and dare I say important gaming experiences which Sword of Kumdor exemplifies. We can't settle for placing YU-NO or Rusty atop curated, canonical lists of the platform's greats and also overlook ambitious/art works like this, not unless all that matters is just ogling these games and their histories at a glance. (Again, I love quite a bit of eroge and better-known PC-X8 darlings, but they're not the end-all-be-all.) Tsubaki was just one talented bedroom-coding polymath among many in that milieu, pushing unwieldy hardware to its limits and daring players to keep up. Our unlikely Master of Blind Touch journeys from the end of one life into the beginnings of another, reassembling a broken world's hopes and dreams from above and within its core. That reconstructive mentality resonates with me, someone who's always willing to give these old, janky but often great PC games their due. You could find all kinds of ideas, stories, genre hybrids, different design paradigms, and truly unique fantasies and realities across East Asian PC games like this, complementing the console/arcade landscape with what those couldn't or didn't provide.

That said, it's not super easy for me to recommend this to anyone starting out with PC-98 emulation or using a real machine. I can think of very few notable games on the system which need this much keyboard configuration to feel all that great to play in long bouts. But it's still one of the most interesting xRPGs on the system—hell, in these genres' history! Not many stories can wield weirdness with purpose and the right amount of restraint like this. Not many edutainment titles dare their players to head into dangerous, troubling circumstances either. And not many are willing to risk players' attention and comfort for the sake of a tonally consistent, draining final act which wraps all loose ends, game loops, and story motifs into one. I have nothing but respect and admiration for Tsubaki's efforts here, and his lack of presence and biographical info even within Japan just saddens me. Regardless, I deem Sword of Kumdor the best way to get into this designer's catalog of bizarre yet relatable JRPGs, with the more computer science-based INSIDERS and Gaia-themed Stellar Sign comprising the rest of these PC-98 tomes. Of course, one might argue we're not getting the whole experience without translations of the dense hintbooks provided with each Tsubaki release, something ASCII Corporation did to help players and persuade educators to include the games in their curricula. But this first translation patch will definitely suffice!

Lethal Company

2023

15 hrs in as of writing this

It's hard to write about Lethal Company because its still in its infancy but I think the groundwork here is very impressive compared to the wave of co-op horror games that have plagued early access these last few years. Zeekerss is a hugely skilled developer with an incredible 5 games under the belt and their (?) knowledge of game design is reflected on Lethal Company. The gameplay loop is simple but the quota makes every expedition a constant weighing of risk when you can't guarantee that you'll make it out either alive or with enough scrap to meet the deadline, and the monster AI strays from the typical -straight line to you until you can hide- that a lot of other games in the genre use when the monster gimmicks wear off-- think of games like Phasmophobia or Forewarned where the enemy AI just goes straight for you even if they do have gimmicks in their enemy design-. The best example is the huge spider which instead of just making a beeline towards the player it'll stay put if it has no webs set up and rather clings to walls which makes the experience much more scary than just having every enemy have the same copy-pasted AI. Obviously anyone who has played the game also knows the voice chat is the strongest selling point of the game due to how well designed it is and is part of what has made the game an overwhelming succes with its indirect marketing proving its worth with every site being filled with funny clips where someone screams viscerally after failing to do parkour jumps or meeting the neckbreaker for the first time.

There's still a lot to polish though. I don't think the loop is completely airtight design wise which can lead to repetition when thriving or frustration on failure when youre on the last day and fail to meet the deadline-- what's the point of the 0 days remaining instance when you can do nothing but land and instantly take off to just reset the run?-.

The outdoor segments also need a lot of work still. Weather can make runs very unfun (looking at you Stormy and Flooded) due to how debilitating they can be without any extra reward therefore making evading the planets the optimal decision which defeats the risk management thats crystallized in a lot of the game's design and the outdoor enemies are just complete balls, specially the Forest Giant who employs the design I complained about earlier. Nothing about the outdoor obstacles feel like they make you switch it up in a satisfying way and just lead to a lot of frustration, especially since a lot of the enemies just like to camp the ship after nightfall.

Lethal Company is, in any case, one of the most fun multiplayer experiences you can have nowadays without emptying your wallet to do so. I hope the game continues to iron out what faults it has right now and just gets even better, and the game as it stands is still really impressive considering its an early access game with a single update