rubenmg

2023

Al final de un juego que tiene plataformas de mentira, sigilo de mentira, puzzles de mentira, una trama distópica haciendo críticas de mentira sobre nada, se revela lo obvio. El juego no tiene ni una pizca de esperanza de que las cosas puedan ir a mejor o de que los seres humanos se comporten como tal, y en los créditos se asegura de mostrar que todo intento de su (pobre y falsa) idea de revolución es devorado por el mercado.

Esto se debe a que es un juego devorado por el mercado, por la tendencia, por la mentira, por hacer porque sí, por ser rentable, porque no cree que los humanos tengan nada que hacer por gusto, porque cree que cualquiera se vende o como poco se acaba engatusando por el mal. En esta secuencia de créditos con tono burlón y desesperanzador, el punto de miseria más alto es uno inesperado y accidental. Entre los mensajes de agradecimiento de los desarrolladores, por lo general nada fuera de lo normal, uno de ellos dedica unas palabras muy sentidas a su madre fallecida recientemente. Después de tantas horas de falsedad choca ver un acto tan escondido y tan humano de la nada, que tarda poco en desaparecer de pantalla mientras una versión ensalzada de ironía de la canción recurrente principal sigue sonando, mientras las imágenes de fondo y la escena post créditos se suceden perpetuando que el ser humano no importa y que no tiene capacidad de empatía ni de amor.

Esto se debe a que es un juego devorado por el mercado, por la tendencia, por la mentira, por hacer porque sí, por ser rentable, porque no cree que los humanos tengan nada que hacer por gusto, porque cree que cualquiera se vende o como poco se acaba engatusando por el mal. En esta secuencia de créditos con tono burlón y desesperanzador, el punto de miseria más alto es uno inesperado y accidental. Entre los mensajes de agradecimiento de los desarrolladores, por lo general nada fuera de lo normal, uno de ellos dedica unas palabras muy sentidas a su madre fallecida recientemente. Después de tantas horas de falsedad choca ver un acto tan escondido y tan humano de la nada, que tarda poco en desaparecer de pantalla mientras una versión ensalzada de ironía de la canción recurrente principal sigue sonando, mientras las imágenes de fondo y la escena post créditos se suceden perpetuando que el ser humano no importa y que no tiene capacidad de empatía ni de amor.

1979

The first great triumph of purely videogame adventure is also one of the first great triumphs of abstraction. The power of Adventure goes beyond the evocative, which is no menial thing, but embraces a wholly abstract language to build a world far more robust and plausible than any other that actively attempts to imitate reality.

It is curious for Colossal Cave Adventure to be one of the main sources of inspiration. It isn’t unexpected that it was taken as a source, as there must not have been many successful examples at the time in the search of adventure, but in how the paths diverged, almost reactionary. Adventure gets rid of words altogether to commit to a total physical world. Consequently, contrary to what abandoning immediate realism may imply, the world of Adventure becomes much more intuitive and believable. There is no longer the conflict of having to puzzle out what kind of commands a word processor is able to understand or not in order to move forward, there is instead the discovery of a system that, while allowing itself to be much simpler, is also much more transparent.

You can grab objects and drop them, birds can also carry (and steal) objects, magnets attract objects contained in the same screen, bridges allow you to cross walls (or whatever they are)... All these rules are not broken at any time and lead to a world that, as Tim Schafer says in the Atari 50 Collection, seems alive, that is able to exist even if the player is not present. Thus, birds can carry away a dragon, a key, a magnet attracting a key, or the player can peek sections of the world while traveling defeated in the belly of a dragon. This contributes in two areas: one of wit from being able to use the available elements in our favor to avoid or tackle obstacles, and another of unpredictability, chaos and life, because given the rules the dislocations of all the elements throughout the map during the game are more than certain. There is always a factor that requires improvisation while continuing the discovery.

It’s difficult to explain how well Adventure applies multiple abstractions to its advantage since many of them have been irremediably absorbed by everything that would come after. As Terry Cavanagh understood in Mr. Platformer, paying homage to similar early titles such as Atari 2600’s Pitfall or Montezuma’s Revenge, these first videogame steps that began to understand abstraction also began to use it as a liberating language. Where entering through a door into a fortress was teleporting into a labyrinth, moving past the edge of the screen was discovering a new piece of the world and doing so repeatedly on the same side discovered a spatially impossible loop.

It's a process of genuine discovery because it doesn’t attempt to clumsily replicate reality, but rather to discover new ways of navigating, interacting and understanding a world. And in the face of all these new, impossible and abstract forms remains a strong, direct and unmistakable sensation: Adventure.

It is curious for Colossal Cave Adventure to be one of the main sources of inspiration. It isn’t unexpected that it was taken as a source, as there must not have been many successful examples at the time in the search of adventure, but in how the paths diverged, almost reactionary. Adventure gets rid of words altogether to commit to a total physical world. Consequently, contrary to what abandoning immediate realism may imply, the world of Adventure becomes much more intuitive and believable. There is no longer the conflict of having to puzzle out what kind of commands a word processor is able to understand or not in order to move forward, there is instead the discovery of a system that, while allowing itself to be much simpler, is also much more transparent.

You can grab objects and drop them, birds can also carry (and steal) objects, magnets attract objects contained in the same screen, bridges allow you to cross walls (or whatever they are)... All these rules are not broken at any time and lead to a world that, as Tim Schafer says in the Atari 50 Collection, seems alive, that is able to exist even if the player is not present. Thus, birds can carry away a dragon, a key, a magnet attracting a key, or the player can peek sections of the world while traveling defeated in the belly of a dragon. This contributes in two areas: one of wit from being able to use the available elements in our favor to avoid or tackle obstacles, and another of unpredictability, chaos and life, because given the rules the dislocations of all the elements throughout the map during the game are more than certain. There is always a factor that requires improvisation while continuing the discovery.

It’s difficult to explain how well Adventure applies multiple abstractions to its advantage since many of them have been irremediably absorbed by everything that would come after. As Terry Cavanagh understood in Mr. Platformer, paying homage to similar early titles such as Atari 2600’s Pitfall or Montezuma’s Revenge, these first videogame steps that began to understand abstraction also began to use it as a liberating language. Where entering through a door into a fortress was teleporting into a labyrinth, moving past the edge of the screen was discovering a new piece of the world and doing so repeatedly on the same side discovered a spatially impossible loop.

It's a process of genuine discovery because it doesn’t attempt to clumsily replicate reality, but rather to discover new ways of navigating, interacting and understanding a world. And in the face of all these new, impossible and abstract forms remains a strong, direct and unmistakable sensation: Adventure.

My main issue with the Zero Escape saga thus far is the personality of the characters: they don't have any. They live and die in a plot of intrigue where they serve only as cogs in the greater mystery.

This should not be a problem, as the games seem to be somewhat aware of the condition of those characters, so everything is directed towards conversations that seek to create enigmas, explain them (or try to) and play with ambiguities. That is, they don't so much seek to be emotional games (luckily, seeing the messy occasional attempts) as intelligent games, which is why they don't shy away from including escape rooms, puzzles and frequent scientific or philosophical references with explicitly cheeky quotes. But they are not smart games.

The deficiency in creating good riddles contained in the escape rooms is more severe, although more concealed, in the main plot. One expects the revelations to show the connections hidden under our noses all this time, but it isn’t like that, particularly in Virtue's Last Reward. Ideas simply succeed one another, none of them particularly imaginative, surprising or interesting on their own or in their cohesion and evidently discrepant when the biggest surprises are revealed, even trying to exemplify them by clarifying small forgettable enigmas without being able to avoid raising at least two major contradictions on the core plot in the process. As you understand more, you also wonder if all this is going to go anywhere. If the component of intrigue, of tension, of intelligence, of emotion, of surprise, if all this and more, has been lost, what is left?

The first installment ended with an ending that, although it came too late and too clumsy, at least achieved something, literalizing a scientific hypothesis into something convincing for its fiction. It made you want to see what more was there to say about it, what could be explored once this hypothesis had materialized, how far could it go.

In Virtue's Last Reward, it is made clear that there was nothing more to say. It tells what is already known and the little that is not, or was less obvious, such as to what extent future actions can have unexpected repercussions on this intricate temporal system, is again greatly reduced in comparison to everything else that gets in the way. Even its worsened structure is surprising. This one, at first appearance more accurate, stating when the story branches and when it reaches different places, loses completely in tension.

Some mystery was preserved in the first game when deciding which teams would go where and how they would be formed, even more so when, being a first entry, anything could still happen. There was no guarantee that a fortuitous decision could not lead to a bad end, and in fact that was often the case in the long run. The structure of Virtue's Last Reward clarifies that it's not so much about choosing as it is about exploring, yet it still feels distracted. The door decision system is both more confusing and more boring, but the final straw comes in the voting ramifications. Something that should be a total psychological confrontation is actually revealed very quickly as a simple formality, the weight that deciding one option or another may have, no matter how much it tries to insist on the supposed human burden carried, comes to nothing.

The last ace up the sleeve to justify the mediocrities that cannot stand their own weight is that the purpose of everything was to expand knowledge horizontally, hence the tree that branches more even if it was with less interesting motives and implications. However, from such an extensive tree of knowledge, ironically, once finished exploring, you come to learn nothing.

This should not be a problem, as the games seem to be somewhat aware of the condition of those characters, so everything is directed towards conversations that seek to create enigmas, explain them (or try to) and play with ambiguities. That is, they don't so much seek to be emotional games (luckily, seeing the messy occasional attempts) as intelligent games, which is why they don't shy away from including escape rooms, puzzles and frequent scientific or philosophical references with explicitly cheeky quotes. But they are not smart games.

The deficiency in creating good riddles contained in the escape rooms is more severe, although more concealed, in the main plot. One expects the revelations to show the connections hidden under our noses all this time, but it isn’t like that, particularly in Virtue's Last Reward. Ideas simply succeed one another, none of them particularly imaginative, surprising or interesting on their own or in their cohesion and evidently discrepant when the biggest surprises are revealed, even trying to exemplify them by clarifying small forgettable enigmas without being able to avoid raising at least two major contradictions on the core plot in the process. As you understand more, you also wonder if all this is going to go anywhere. If the component of intrigue, of tension, of intelligence, of emotion, of surprise, if all this and more, has been lost, what is left?

The first installment ended with an ending that, although it came too late and too clumsy, at least achieved something, literalizing a scientific hypothesis into something convincing for its fiction. It made you want to see what more was there to say about it, what could be explored once this hypothesis had materialized, how far could it go.

In Virtue's Last Reward, it is made clear that there was nothing more to say. It tells what is already known and the little that is not, or was less obvious, such as to what extent future actions can have unexpected repercussions on this intricate temporal system, is again greatly reduced in comparison to everything else that gets in the way. Even its worsened structure is surprising. This one, at first appearance more accurate, stating when the story branches and when it reaches different places, loses completely in tension.

Some mystery was preserved in the first game when deciding which teams would go where and how they would be formed, even more so when, being a first entry, anything could still happen. There was no guarantee that a fortuitous decision could not lead to a bad end, and in fact that was often the case in the long run. The structure of Virtue's Last Reward clarifies that it's not so much about choosing as it is about exploring, yet it still feels distracted. The door decision system is both more confusing and more boring, but the final straw comes in the voting ramifications. Something that should be a total psychological confrontation is actually revealed very quickly as a simple formality, the weight that deciding one option or another may have, no matter how much it tries to insist on the supposed human burden carried, comes to nothing.

The last ace up the sleeve to justify the mediocrities that cannot stand their own weight is that the purpose of everything was to expand knowledge horizontally, hence the tree that branches more even if it was with less interesting motives and implications. However, from such an extensive tree of knowledge, ironically, once finished exploring, you come to learn nothing.

2024

Uncomfortable at first for its unique and daring control without abandoning the arcade spirit. Having to control two avatars at once makes the task already complex, but the various restrictions and synergies are the blossoming factor. It is not simply that the flower has to be kept in the defense and the wasp must look for the offense, both beings deplete their health and have to join together to mutually recover, along other essential offensive actions that require the ability to coordinate both creatures' positions. On top of that, the avatars cannot even go completely free, there is a limit on the separation length that makes it a constant to maneuver both bodies. All this is also supported by enemies that, taking advantage of the circular arena, tend to chase the flower, making each screen a kind of constant multiple double tag game.

The gratification of getting to control the two avatars to the point of being able to face an arcade that does not hold back its frenzy ends up reminiscing something. It is a similar feeling to picking up a guitar for the first time, having to look down as your clumsy fingers slowly place themselves on each fret, and end up making the instrument another part of your body like the vocal cords themselves.

The gratification of getting to control the two avatars to the point of being able to face an arcade that does not hold back its frenzy ends up reminiscing something. It is a similar feeling to picking up a guitar for the first time, having to look down as your clumsy fingers slowly place themselves on each fret, and end up making the instrument another part of your body like the vocal cords themselves.

It is an obvious game about connections, with the stories of the various protagonists being interwoven through diverse means. These connections are also a victory of good faith against evil. While the evil plan in the shadows is responsible for causing havoc always one step ahead of all of Shibuya, the player's power to guide everyone into the best course always prevails.

It is not even a subtle push on the characters as they step into dilemmas, it is a force so powerful that it is capable of making arbitrary decisions that can save the day. This is why the game allows itself to indulge constantly in its comedic tone. Including the bad endings. It is not afraid to paint a catastrophe as a mere joke because it knows the situation can be saved, they are a mere pastime of a daydream, or perhaps a nightmare, that could but never will be.

These connections are also implicit in the plot itself. As the climax is reached, all interpersonal conflicts are eventually ironed out to form a cohesive whole. The game, in the midst of these impossible to avoid threads that take place in Shibuya, allows itself to include a plot with a character isolated, both from the physical outside and from his family, and help him reconnect with his loved ones and the world through gestures as simple as an anonymous message on an online pop singer fan forum or a bodyguard (a buffoon in actual fact) put on assignment who nevertheless genuinely cares about his objective, his friend, beyond duty.

It is strange, but each session felt thoroughly pleasant, watching faces intermingle between stories and laughing, somewhat cruelly but harmlessly at heart, at the crossovers as they did not even suspect the weight that their encounters carried. On occasion, the protagonists are ignorant of why or how a decision or a connection would end one way or the other. Using the shield of humor, what really hides behind is a faith in that the schemes of evil cannot overcome an unexplainable and unstoppable goodness.

It is not even a subtle push on the characters as they step into dilemmas, it is a force so powerful that it is capable of making arbitrary decisions that can save the day. This is why the game allows itself to indulge constantly in its comedic tone. Including the bad endings. It is not afraid to paint a catastrophe as a mere joke because it knows the situation can be saved, they are a mere pastime of a daydream, or perhaps a nightmare, that could but never will be.

These connections are also implicit in the plot itself. As the climax is reached, all interpersonal conflicts are eventually ironed out to form a cohesive whole. The game, in the midst of these impossible to avoid threads that take place in Shibuya, allows itself to include a plot with a character isolated, both from the physical outside and from his family, and help him reconnect with his loved ones and the world through gestures as simple as an anonymous message on an online pop singer fan forum or a bodyguard (a buffoon in actual fact) put on assignment who nevertheless genuinely cares about his objective, his friend, beyond duty.

It is strange, but each session felt thoroughly pleasant, watching faces intermingle between stories and laughing, somewhat cruelly but harmlessly at heart, at the crossovers as they did not even suspect the weight that their encounters carried. On occasion, the protagonists are ignorant of why or how a decision or a connection would end one way or the other. Using the shield of humor, what really hides behind is a faith in that the schemes of evil cannot overcome an unexplainable and unstoppable goodness.

2023

That the most oppressive dungeons to memory barely have any enemies is already surprising, that the fear is tangible even when not a single monster is encountered is exceptional. It is not just the great atmosphere designed to overwhelm (the darkness, the narrow corridors, the labyrinths, the ambiguous noises) but the craving for which, originally, any dungeon calls for adventure. Search for treasures (or scrap…) and try to control the craving for that one more bit as the time limit approaches, the monsters multiply and the risk of losing absolutely everything looms around the corners. A necessary craving, because money is needed to keep playing, and encouraged, because the more you get, the more you can buy to have easier incursions. With the variety of threats to encounter, the behaviors and ways of dealing with each monster being notably different, and the randomness of each round, there is no safe plan.

To finally find the lost sense that the dungeon originally had, the incursion is carried out by four people in first person view, not a single entity capable of controlling four bodies. The proximity chat helps to confuse more than to coordinate, also to frighten, it will be common to be scared of the scare of the scare from someone who wrongly jumped because of a strange harmless silhouette. Even monitoring on the ship, an assignment that carries quite some strategy behind, is by no means a menial, minor or boring task. The tension of those in the dungeon is translated and transmitted through the viewing of the red dots of undefined danger, the communications through walkie working with the expected quality (none) and the possibility of a dynamic role where you can always take all your bravery and ruin a game by trying to be the rescuing hero of the party.

Nowadays, to think of dungeons is to think of playing roulette while devastating everything in the path with the aim of conquering. At some point, the dungeon overwhelmed the explorer’s desire, the act of making a profit being only a loan from the infinite terror that the darkness hides. That is the dungeon and the adventure of Lethal Company.

To finally find the lost sense that the dungeon originally had, the incursion is carried out by four people in first person view, not a single entity capable of controlling four bodies. The proximity chat helps to confuse more than to coordinate, also to frighten, it will be common to be scared of the scare of the scare from someone who wrongly jumped because of a strange harmless silhouette. Even monitoring on the ship, an assignment that carries quite some strategy behind, is by no means a menial, minor or boring task. The tension of those in the dungeon is translated and transmitted through the viewing of the red dots of undefined danger, the communications through walkie working with the expected quality (none) and the possibility of a dynamic role where you can always take all your bravery and ruin a game by trying to be the rescuing hero of the party.

Nowadays, to think of dungeons is to think of playing roulette while devastating everything in the path with the aim of conquering. At some point, the dungeon overwhelmed the explorer’s desire, the act of making a profit being only a loan from the infinite terror that the darkness hides. That is the dungeon and the adventure of Lethal Company.

2008

It is nice that there is a store management component and that you have to adapt to your clients to force yourself into seeing fashion with other eyes, out of your comfort zone and adding charisma to the different customers along the way. After all, if it was more of a toy where you simply dress your custom character as desired since the very beginning, in the hopes of fulfilling a sort of dressing freedom, it would struggle to compete against the at the time already plentiful online dress up games and, specially considering children as the target audience in mind, simply drawing characters and their looks with literal boundless possibilities and references to borrow inspiration from.

The management of the shop is also thought less as a strategy game and more about having a bit of everything in reserve to please everyone. To please not because of clients being walking cash bags (the monetary aspect is so irrelevant that the game will give you funds for free if you somehow get close to being broke) but because of an honest intent to see them as characters, mostly defined by their stylistic preferences. They have their little backgrounds and will even ask you to hang out when enough confidence is built, it is a communication exercise by understanding them through fashion.

Having said that, there is something missing around there. Serving your customers becomes tedious, even when the requests try to be varied, and these same people that the game wanted you to care about individually become a certain mass of tasks to complete to get to the next shop ranking to get to the next fashion contest to eventually get the credits rolling. A disheartening, although perhaps accurate, depiction of the job and the career, a subconscious design output never addressed nonetheless.

My view may be wrong, since the game will continue living on long after you win whatever you want to win, yet somehow it seems trapped between two extremes. One can just wonder if it could have been better by compromising either with being a relaxed game to check once in a while without pressure, just out of sheer interest, or a more mechanically asking game, perhaps even taking more fantastic approaches to present an active challenge while making you care about fashion.

Or maybe I am resentful and envious that women have better style possibilities.

The management of the shop is also thought less as a strategy game and more about having a bit of everything in reserve to please everyone. To please not because of clients being walking cash bags (the monetary aspect is so irrelevant that the game will give you funds for free if you somehow get close to being broke) but because of an honest intent to see them as characters, mostly defined by their stylistic preferences. They have their little backgrounds and will even ask you to hang out when enough confidence is built, it is a communication exercise by understanding them through fashion.

Having said that, there is something missing around there. Serving your customers becomes tedious, even when the requests try to be varied, and these same people that the game wanted you to care about individually become a certain mass of tasks to complete to get to the next shop ranking to get to the next fashion contest to eventually get the credits rolling. A disheartening, although perhaps accurate, depiction of the job and the career, a subconscious design output never addressed nonetheless.

My view may be wrong, since the game will continue living on long after you win whatever you want to win, yet somehow it seems trapped between two extremes. One can just wonder if it could have been better by compromising either with being a relaxed game to check once in a while without pressure, just out of sheer interest, or a more mechanically asking game, perhaps even taking more fantastic approaches to present an active challenge while making you care about fashion.

Or maybe I am resentful and envious that women have better style possibilities.

Games usually work best at acknowledging that less is more. Making a simple dialogue box with a scarce message will leave abstraction to fill the blanks better than the common poor staging of having a high detail 3D character lip syncing its dialogue, resulting in the usual videogame ugliness of trying to look genuine. And in games where, like Dragon’s Dogma, resources didn't seem to be plentiful, it only looks worse.

It isn't that bad that every character is the worst cosplayer of a medieval human from the robot world, everything is an excuse to go on an adventure after all. Even the initial premise, create a character, see how their heart is taken by a dragon, see the character survive, kill the dragon, is somehow totally lost before you step out in the field, not knowing the amount of hours that such a direct premise will take to move to its next obvious point.

The combat is sometimes there. In the more open areas, it can be easily ignored, no group of enemies will ever figure out what to do if you run in a straight line away from them. Perhaps the never knowing, though thankfully always teleporting, companions may get caught in their urge to kill anything on their view. Supposedly, traps are prepared on the way to catch you off guard. Realistically, these traps, already inoffensive when first encountered, are turned on their heads when noticing that the game obviously respawns the same enemy placement every time. You are the one expecting them. This is why escaping is so intentionally easy, repeating the same fights is tedious, and from a certain point they will not be worth to repeat because of any loot, experience, gold, quests or, impossible to imagine, joy for action.

Dungeons are better received since their close and tight spaces, sometimes even interesting to navigate, don't allow for such easy escapes. Instead, you can contemplate how most attacks provoke the same physical response as punching a wall and will reach to the conclusion of what Dragon's Dogma is really about. There is no force in the action, no world to adventure, no companions to unmute, no real characters freed from being quest giving robots, there are only levels to up, money to gain, equipment to upgrade and quests to complete. Just a number check to advance. Even the premise of the adventure driven by greed gets lost in the constant recollection of worthless nonsense. Finding gold is finding a treasure. Finding a pile of trash that may or may not contain gold that you don’t even know what to use for anymore is just finding a pile of trash.

The same as our main character, a moving body without a heart, just because. It is Dragon Quest 1 but longer and with the sporadic bits of charm lost. And that one was already bad.

It isn't that bad that every character is the worst cosplayer of a medieval human from the robot world, everything is an excuse to go on an adventure after all. Even the initial premise, create a character, see how their heart is taken by a dragon, see the character survive, kill the dragon, is somehow totally lost before you step out in the field, not knowing the amount of hours that such a direct premise will take to move to its next obvious point.

The combat is sometimes there. In the more open areas, it can be easily ignored, no group of enemies will ever figure out what to do if you run in a straight line away from them. Perhaps the never knowing, though thankfully always teleporting, companions may get caught in their urge to kill anything on their view. Supposedly, traps are prepared on the way to catch you off guard. Realistically, these traps, already inoffensive when first encountered, are turned on their heads when noticing that the game obviously respawns the same enemy placement every time. You are the one expecting them. This is why escaping is so intentionally easy, repeating the same fights is tedious, and from a certain point they will not be worth to repeat because of any loot, experience, gold, quests or, impossible to imagine, joy for action.

Dungeons are better received since their close and tight spaces, sometimes even interesting to navigate, don't allow for such easy escapes. Instead, you can contemplate how most attacks provoke the same physical response as punching a wall and will reach to the conclusion of what Dragon's Dogma is really about. There is no force in the action, no world to adventure, no companions to unmute, no real characters freed from being quest giving robots, there are only levels to up, money to gain, equipment to upgrade and quests to complete. Just a number check to advance. Even the premise of the adventure driven by greed gets lost in the constant recollection of worthless nonsense. Finding gold is finding a treasure. Finding a pile of trash that may or may not contain gold that you don’t even know what to use for anymore is just finding a pile of trash.

The same as our main character, a moving body without a heart, just because. It is Dragon Quest 1 but longer and with the sporadic bits of charm lost. And that one was already bad.

2018

Finishing Lumines is making it through an all night dance. Its board, wider than tall, is less inviting to ordering, like usual on the genre, and more to finding comfortable spots. Some like to place on the sides, some more at the center, some like populated spaces, some prefer to start on quiet corners.

The pieces of Lumines don’t disappear, they go out to take a smoke after finding someone to talk to for a while, and then come back. Those pieces start dancing on their own, they are naturally attracted to form groups, the bigger the better, and sometimes some magician out of nowhere will grab everyone by the arm forming a chain. Raindrops on a windshield. Surviving through the night is hard. It is not because it is not fun, some songs you may not care about, others you may dislike, but once you are in, there are no enemies, it is impossible to escape. As the night goes on that empty board gets lively, sometimes it is hard to hold on and you need to quit early. You will try again another night.

Somehow, you know the perfect night should not exist. Mathematically, anything should go wrong at any time, the variables cannot escape chance. Somehow, that ideal night eventually comes, the last song is announced, the celebration of the celebration is done, the sun rises and everyone goes home. Nothing happened during that time, time just flew by, and somehow something unforgettable to look back forever on in the years to come had been forged.

This is what heaven looks like:

https://youtu.be/U6xNSg8rFPE?si=T2sZ98gGiZ0YSnCO&t=1763

The pieces of Lumines don’t disappear, they go out to take a smoke after finding someone to talk to for a while, and then come back. Those pieces start dancing on their own, they are naturally attracted to form groups, the bigger the better, and sometimes some magician out of nowhere will grab everyone by the arm forming a chain. Raindrops on a windshield. Surviving through the night is hard. It is not because it is not fun, some songs you may not care about, others you may dislike, but once you are in, there are no enemies, it is impossible to escape. As the night goes on that empty board gets lively, sometimes it is hard to hold on and you need to quit early. You will try again another night.

Somehow, you know the perfect night should not exist. Mathematically, anything should go wrong at any time, the variables cannot escape chance. Somehow, that ideal night eventually comes, the last song is announced, the celebration of the celebration is done, the sun rises and everyone goes home. Nothing happened during that time, time just flew by, and somehow something unforgettable to look back forever on in the years to come had been forged.

This is what heaven looks like:

https://youtu.be/U6xNSg8rFPE?si=T2sZ98gGiZ0YSnCO&t=1763

2021

Easy to see as an absolute opposite of Tetris (and descendants) by design. The usual squared and stiff pieces here are rounded fruits that will never stop moving, not only after you drop them but as long as anything is moving along on the board. The same can be said about how both types of games manage time. The ever increasing urge to make decisions in Tetris is not explicitly here, you can take all the time in the world to decide every single move, and yet it is a game where time is fundamental. Instead of dropping pieces of fruit fast because the system forces you to, you make the drops fast (or not) because the board can and will go out of control thanks to the living chain reaction of every collision.

It could be argued that by not taking the, by now quite trite, increasing speed pressure, Suika Game isn’t that good at building tension as the game goes on. Yet, the compromise on a spatial and physical game that can never be erased, only temporarily reduced, is enough to make every cherry count until the very end. There is the notable exception of being able to mix together two watermelons consistently, though humanity is still not there to behold such a level of refinement, addiction or both.

It could be argued that by not taking the, by now quite trite, increasing speed pressure, Suika Game isn’t that good at building tension as the game goes on. Yet, the compromise on a spatial and physical game that can never be erased, only temporarily reduced, is enough to make every cherry count until the very end. There is the notable exception of being able to mix together two watermelons consistently, though humanity is still not there to behold such a level of refinement, addiction or both.

2018

Manages to make a dungeon of just a few small areas feel immense by knowing its own language. Reduce the visible area, put enemies that, even if scarce, always pose a game ending risk if approached without care, make the environment interactive in unpredictable ways by always randomizing the looting results and do not even take for granted that saving the game is a safe action. Each incursion from each load (or from the very beginning) feels like an expedition, similar to something like the first Dragon Quest or the first Resident Evil. Voyages where, even if ending up in death, discovery is enough reason to push a little further in.

Even knowing that the game has become known because of its harsh aspects, perhaps what lacks the most is a more unforgiving commitment to punishment (later in added higher difficulties seem to approve). Fear & Hunger asks you to use everything to your advantage, and finding exploits fits as another piece of the game. But, while a really robust game will make the exploits’ exploration look like another foreseen step of the process, some of the shortcuts to ease your travels through this dungeon are more akin to permanent uninteresting rewards for finally figuring out, or exploring enough, to break a layer on the asphyxiating design. The decision to have saved games at all also incentives to push your unlimited chances like playing roulette in certain situations, betraying some of the most interesting elements of the proposal, like the threatening unknown atmosphere and the idea of improvising against upcoming surprises. Risks should stay risks instead of retries of luck.

Even if I wish the game could press harder, or smarter, its initial hours of discovery and commitment to an open mysterious exploration are more than enough to construct a dungeon with enough presence of its own. And it also may be the game with the highest amount of handmade d

Even knowing that the game has become known because of its harsh aspects, perhaps what lacks the most is a more unforgiving commitment to punishment (later in added higher difficulties seem to approve). Fear & Hunger asks you to use everything to your advantage, and finding exploits fits as another piece of the game. But, while a really robust game will make the exploits’ exploration look like another foreseen step of the process, some of the shortcuts to ease your travels through this dungeon are more akin to permanent uninteresting rewards for finally figuring out, or exploring enough, to break a layer on the asphyxiating design. The decision to have saved games at all also incentives to push your unlimited chances like playing roulette in certain situations, betraying some of the most interesting elements of the proposal, like the threatening unknown atmosphere and the idea of improvising against upcoming surprises. Risks should stay risks instead of retries of luck.

Even if I wish the game could press harder, or smarter, its initial hours of discovery and commitment to an open mysterious exploration are more than enough to construct a dungeon with enough presence of its own. And it also may be the game with the highest amount of handmade d

2005

The ultimate game about shooting, a genre often overwhelmed by getting shot. You shoot to kill, shoot to stun, shoot to stop projectiles, shoot to blow explosives, shoot to deactivate traps, you even shoot to be able to not shoot for a bit. You are a microdose sniper, not just because of the need to find the spot, stand still, aim and take the shot, compensating constantly for pulse and breath, but also keeping the laser spot, no matter if the weapon is a shotgun, with one of the comical exceptions being the sniper rifle itself.

Arguably, the main character should be the Merchant, a literal manifestation of gun Doraemon, yet again, this is not a game about weapons. You control Leon because, apart from being hot, he is the shooter.

Arguably, the main character should be the Merchant, a literal manifestation of gun Doraemon, yet again, this is not a game about weapons. You control Leon because, apart from being hot, he is the shooter.

2012

On the surface, Jet Set Radio may seem like an explicit expression of the urban teenage outrage from something like Tony Hawk games, you do graffiti around town, the police and even the army pursue you, you help an underground illegal radio, everyone is dancing all the time, the visual style is a colorful explosive display of liveliness. On the inside, this is nothing more than the envelope of an identity crisis lie.

What this really is, compared to Tony Hawk, is a simplified version where about two action buttons carry all the movement. The complex techniques of the older game are now automated, which may sound like an improvement in the flow of movement, yet ends up backfiring, as this automation also means that it is much harder to predict what the character is even going to do. In consequence, penalties are also relieved, falling down, even after impossible falls, is a rare sight, grinding rails no longer requires keeping any balance at all. These watered down decisions exist also because of a more careless attention to detail on movement, where something essential as jumps often becomes unexpected leaps of faith. This lack of attention is to be expected.

Tony Hawk games totally committed to translating skating into videogame through an exaggerated arcade abstraction. Where impossible jumps were possible, still an essence was maintained regardless of the surrealism. You had two minutes, a song, and a place where to find your own style to be turned into your combo tricks playground. Jet Set Radio arcade capacities are but a mere curiosity. Perhaps in recognition of not being able to find a game where moving around was satisfactory enough, perhaps in disbelief of the power of arcade, Jet Set Radio is nothing but a game of following steps and getting interrupted.

No longer is the city there as your canvas, the graffiti spots to paint here are clearly marked with red arrows. Those missions at least still leave up to you the routes to get to the different marked points whereas the duels, in Tony Hawk an even more concentrated and heavily penalized one minute jam, are now the epitome of identity robbery. To show your value to others, you copy their exact movements.

The two minute arcade do what you want without additives is now an infinitely generous timed mission full of stops. Start the mission and get a cutscene. Trigger the police, reinforcements, whatever, get another cutscene, even in midair. Pause and open up your map to locate your missing objectives. Search for health refills if you get too many hits. Perform an incredible stunt, like grinding a rail without pressing a button, and get a replay highlight. Paint a graffiti, halt your movement completely regardless of acceleration and complete a quick time event standing still for seconds.

Tony Hawk games, if cynically seen, may look like a messy license mashup in an attempt to grab attention wherever it could, but, above everything, contained a clear idea on what the urban movement on top of a skate meant in its own arcade terms. Jet Set Radio has clear ideas on the aesthetic it wants to reach, but at its heart is, at best, just a confused teenager that prefers to watch the style from afar, afraid of taking the wheels and falling down.

What this really is, compared to Tony Hawk, is a simplified version where about two action buttons carry all the movement. The complex techniques of the older game are now automated, which may sound like an improvement in the flow of movement, yet ends up backfiring, as this automation also means that it is much harder to predict what the character is even going to do. In consequence, penalties are also relieved, falling down, even after impossible falls, is a rare sight, grinding rails no longer requires keeping any balance at all. These watered down decisions exist also because of a more careless attention to detail on movement, where something essential as jumps often becomes unexpected leaps of faith. This lack of attention is to be expected.

Tony Hawk games totally committed to translating skating into videogame through an exaggerated arcade abstraction. Where impossible jumps were possible, still an essence was maintained regardless of the surrealism. You had two minutes, a song, and a place where to find your own style to be turned into your combo tricks playground. Jet Set Radio arcade capacities are but a mere curiosity. Perhaps in recognition of not being able to find a game where moving around was satisfactory enough, perhaps in disbelief of the power of arcade, Jet Set Radio is nothing but a game of following steps and getting interrupted.

No longer is the city there as your canvas, the graffiti spots to paint here are clearly marked with red arrows. Those missions at least still leave up to you the routes to get to the different marked points whereas the duels, in Tony Hawk an even more concentrated and heavily penalized one minute jam, are now the epitome of identity robbery. To show your value to others, you copy their exact movements.

The two minute arcade do what you want without additives is now an infinitely generous timed mission full of stops. Start the mission and get a cutscene. Trigger the police, reinforcements, whatever, get another cutscene, even in midair. Pause and open up your map to locate your missing objectives. Search for health refills if you get too many hits. Perform an incredible stunt, like grinding a rail without pressing a button, and get a replay highlight. Paint a graffiti, halt your movement completely regardless of acceleration and complete a quick time event standing still for seconds.

Tony Hawk games, if cynically seen, may look like a messy license mashup in an attempt to grab attention wherever it could, but, above everything, contained a clear idea on what the urban movement on top of a skate meant in its own arcade terms. Jet Set Radio has clear ideas on the aesthetic it wants to reach, but at its heart is, at best, just a confused teenager that prefers to watch the style from afar, afraid of taking the wheels and falling down.

2023

While a direct translation to 3D of a game that just with the title “Colossal Cave Adventure” is an evident good idea, the too literally attached attempt to homage the original weighs down the experience.

As expected, the huge cave is wonderfully modeled, just as the hazy original text suggested, to maintain an overwhelming first impression. In the lack of confidence of pure exploration, also known as pure adventure, the original ended up being turned into a long term strategy game where to plan out your movements according to illogical trial and error procedures discovered in previous playthroughs. An abandonment of genuine geographical/magical discovery for a more bland, gamey repetition exercise.

This remake not only maintains the exact same problem, but adds a couple of its own when the senseless non-geographical elements need to be translated. Moments that still felt genuine in the original like the pirate or the dwarves appearing out of nowhere didn't need an explanation because of the turn based text narration abstraction itself. This, now in a literal 3D representation, means that these same characters appear and disappear out of magical smoke as you get paralyzed waiting for them to mess with you. This also applies to some of the puzzles. It happens in the puzzles that retained some sense, like being unable to carry the gold nugget to an upper floor, here being contradicted by the floors being separated explicitly with samey stairs in which some arbitrarily allow you to carry the gold and some others not. And it happens in the puzzles that didn’t make that much sense, the spatially impossible labyrinths may get a pass because of the inevitable omissions of text narration nature, but here it is just an unacceptable same looking room where the obvious loading screens magic trick just comes off as cheap.

Since there are obvious downsides to the literal transformation of the blandest parts in the original game, it would be nice to embrace the spatial twists and its own 3D geographical nature in all its glory without additives. What a coincidence that the “adventure” part was dropped from the title.

As expected, the huge cave is wonderfully modeled, just as the hazy original text suggested, to maintain an overwhelming first impression. In the lack of confidence of pure exploration, also known as pure adventure, the original ended up being turned into a long term strategy game where to plan out your movements according to illogical trial and error procedures discovered in previous playthroughs. An abandonment of genuine geographical/magical discovery for a more bland, gamey repetition exercise.

This remake not only maintains the exact same problem, but adds a couple of its own when the senseless non-geographical elements need to be translated. Moments that still felt genuine in the original like the pirate or the dwarves appearing out of nowhere didn't need an explanation because of the turn based text narration abstraction itself. This, now in a literal 3D representation, means that these same characters appear and disappear out of magical smoke as you get paralyzed waiting for them to mess with you. This also applies to some of the puzzles. It happens in the puzzles that retained some sense, like being unable to carry the gold nugget to an upper floor, here being contradicted by the floors being separated explicitly with samey stairs in which some arbitrarily allow you to carry the gold and some others not. And it happens in the puzzles that didn’t make that much sense, the spatially impossible labyrinths may get a pass because of the inevitable omissions of text narration nature, but here it is just an unacceptable same looking room where the obvious loading screens magic trick just comes off as cheap.

Since there are obvious downsides to the literal transformation of the blandest parts in the original game, it would be nice to embrace the spatial twists and its own 3D geographical nature in all its glory without additives. What a coincidence that the “adventure” part was dropped from the title.

2023

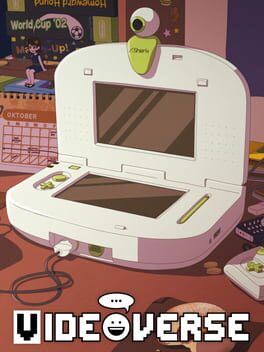

A conglomeration of impossible nostalgias: Nintendo DS tactile device, messenger chats, barely functional webcams, two colored pixelated games and UI, fan art forums, 2000s trends posters… Videoverse basically takes whatever is convenient from each place while giving a kind of immortal internet nostalgia, where seeing the face of someone from another country in a laggy exchange is a kind of magical event, both in its unimaginable existence just a few decades ago and in its low fidelity technological mystique. This blurry yet distinct mass also carries a meaning of both the degree of precision at recalling our memories and how videogames work better with few charismatic gestures, scarce and giant pixels changing the face expression to tell absolutely everything.

In this virtual reality, completely opening yourself is both the only possible and most risky place to do so. Everything is volatile, logging off is erasing your existence and the servers shutting down is the end of the world on top of your desk. As messy as it may be, Videoverse is undeniably a home. The more times you log in, the more those nicknames become your neighbors. For a teenager still figuring out the world, it is as easy to assimilate as reality.

In this place where it is technically impossible to tell apart true from false, love is still the biggest unexplainable truth.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wcKsxHURj24

In this virtual reality, completely opening yourself is both the only possible and most risky place to do so. Everything is volatile, logging off is erasing your existence and the servers shutting down is the end of the world on top of your desk. As messy as it may be, Videoverse is undeniably a home. The more times you log in, the more those nicknames become your neighbors. For a teenager still figuring out the world, it is as easy to assimilate as reality.

In this place where it is technically impossible to tell apart true from false, love is still the biggest unexplainable truth.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wcKsxHURj24