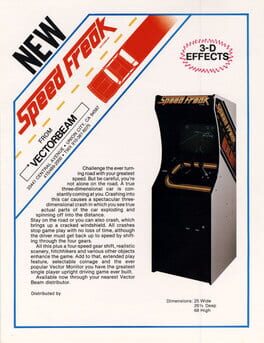

Speed Freak is a monochrome vector arcade game created by Vectorbeam in 1979. It is a behind-the-wheel driving simulation where the driver speeds down the computer generated road past other cars, hitchikers, trees, cows and cacti. Occasionally a plane will fly overhead towards the screen. One must avoid crashing into these objects and complete the race in the alloted time. The player can crash as many times as he wants before the time runs out and players were treated to two different crash animations. The first was a simple cracked windshield effect, the second was a crash where the car explodes into car parts that fly through the air.

Reviews View More

Very similar to “Night Driver”, but with much better graphics and with interactions of the scenario directly in the gameplay, besides some details and objects that give life to the small world of the game. Regarding the gameplay, it keeps the same base of other games only with differences in the scenario.

The very first "realistic" arcade racing video games started off simplistic and barely evocative of what they promised players, but Speed Freak, the first example using vector graphics, does the night-racer concept best out of them all. It must have seemed like a huge leap forward upon release in 1979, three years after Atari engineer Dave Shepperd and his team used Reiner Forest's Nurburgring-1 as the basis for Night Driver (and then Midway's close competitor, 280 Zzzap). Representing the road with just scaling road markers zooming by, in and out of the vanishing point, was impressive enough in the late-'70s, yet Vectorbeam saw the potential for this concept if brought into wireframe 3D. Without changing the simple and immediate goal of driving as fast, far, and crash-less as possible, the company made what I'd tentatively call the best commercial driving sim of the decade, albeit without the fancy skeuomorphic cabinets of something like Fire Truck.

One coin nets players two minutes total of driving, dodging, shifting, and hopefully some high scorin'. Like its stylistic predecessors, the cabinet features a wheel and gated stick shift, giving you something tactile to steer and manage speed with other than the pedals. And that vector display! This expensive but awe-inspiring video tech debuted in arcade format back in '77 when Larry Rosenthal from MIT debuted a fast yet affordable Spacewar! recreation using these new screen drawing methods. Whereas Dr. Forest's early '76 German racing sim drew a basic road surface and lit up bulbs placed towards the glass to fake road edges, Atari and Midway used very early microprocessors and video ROM chips to render rasterized equivalents. Here, though, vivid scanlines of light emanated from the screen at a human-readable refresh rate, with far more on-road and off-road detail than before. Clever scaling of wiry objects on screen gives the impression of 3D perspective, and crashing leads to a broken windshield effect! All these features would have made this feel more comprehensive and immersive for arcade-goers than its peers, even compared to the most luxurious of electromechanical racing installations.

Speed Freak itself, though, isn't a big leap in complexity and depth of play, nor does it use the extended-time mechanic found in 280 Zzzap. You just have to reach and maintain max speed without crashing either off the course or into oncoming objects, like other cars or signposts. It's all about speeding down the darkness with reckless abandon, nabbing those top scores over drivers who keep bailing within this strict time limit. Momentum's a little funky at first, but no more unlifelike or difficult to work with than in Night Driver and its direct precursor. The game does let you know if you're in danger of an accident by sounding a tire squeal, among other small details that build an illusion of world-building here. I wish there was not just a way to extend play, but also see recommended cornering speeds for upcoming turns, rather than having to guess at a glance how far to brake and/or shift. That's one aspect 280 Zzzap has over this and the Atari game, for what it's worth.

Vector-based 3D driving faire like this had a brief heyday in '79 and the following year, but it wouldn't be long until both SEGA and Namco fought back. Their jaw-dropping third-person racers Turbo and Pole Position proved that colorful, "super-scaling" raster graphics were just as much a match for the relatively spartan but flexible vector stuff. In fact, more players cottoned on to these Japanese competitors, both for the added skill ceiling and game loop variety which developers at neither Cinematronic nor Vectorbeam could match. Still, despite how much more I love those Golden Age 2D and pseudo-3D skidfests from the industry titans, I think there was a lot of potential explored in Speed Freak, something more akin to military simulators but for the masses. Affordable home computers and their game creators wouldn't touch this genre for years to come, and the closest you could get on VCS and competing any-game consoles never stood a chance at reproducing this experience. Rosenthal's brief stint running Vectorbeam, a bright light of innovation and visual achievement in the industry, ended the same year this came out, all because Barrer bombed and its manufacturing costs fatally wounded the company. If they had found more market success and iterated on vector tech as fast as he'd introduced it, who knows if the Vectrex and similar projects might have fared better?

Today you can only play Speed Freak on a properly maintained real-life board or, thankfully, through MAME. It's a guilty pleasure of mine, easy to rebind for controllers and a neat subject for screenshots. Maybe the likes of Digital Eclipse, Night Dive, or another prestigious studio could figure out the licensing situation for these formative vector games and get all the experts in one room to make an Atari 50-caliber collection one day. Or maybe that window's passed, given how many industry people from the time have passed on or simply become unavailable. Give this a try regardless! It's simultaneously the start and end of an era, hiding in plain sight among its own kind.

One coin nets players two minutes total of driving, dodging, shifting, and hopefully some high scorin'. Like its stylistic predecessors, the cabinet features a wheel and gated stick shift, giving you something tactile to steer and manage speed with other than the pedals. And that vector display! This expensive but awe-inspiring video tech debuted in arcade format back in '77 when Larry Rosenthal from MIT debuted a fast yet affordable Spacewar! recreation using these new screen drawing methods. Whereas Dr. Forest's early '76 German racing sim drew a basic road surface and lit up bulbs placed towards the glass to fake road edges, Atari and Midway used very early microprocessors and video ROM chips to render rasterized equivalents. Here, though, vivid scanlines of light emanated from the screen at a human-readable refresh rate, with far more on-road and off-road detail than before. Clever scaling of wiry objects on screen gives the impression of 3D perspective, and crashing leads to a broken windshield effect! All these features would have made this feel more comprehensive and immersive for arcade-goers than its peers, even compared to the most luxurious of electromechanical racing installations.

Speed Freak itself, though, isn't a big leap in complexity and depth of play, nor does it use the extended-time mechanic found in 280 Zzzap. You just have to reach and maintain max speed without crashing either off the course or into oncoming objects, like other cars or signposts. It's all about speeding down the darkness with reckless abandon, nabbing those top scores over drivers who keep bailing within this strict time limit. Momentum's a little funky at first, but no more unlifelike or difficult to work with than in Night Driver and its direct precursor. The game does let you know if you're in danger of an accident by sounding a tire squeal, among other small details that build an illusion of world-building here. I wish there was not just a way to extend play, but also see recommended cornering speeds for upcoming turns, rather than having to guess at a glance how far to brake and/or shift. That's one aspect 280 Zzzap has over this and the Atari game, for what it's worth.

Vector-based 3D driving faire like this had a brief heyday in '79 and the following year, but it wouldn't be long until both SEGA and Namco fought back. Their jaw-dropping third-person racers Turbo and Pole Position proved that colorful, "super-scaling" raster graphics were just as much a match for the relatively spartan but flexible vector stuff. In fact, more players cottoned on to these Japanese competitors, both for the added skill ceiling and game loop variety which developers at neither Cinematronic nor Vectorbeam could match. Still, despite how much more I love those Golden Age 2D and pseudo-3D skidfests from the industry titans, I think there was a lot of potential explored in Speed Freak, something more akin to military simulators but for the masses. Affordable home computers and their game creators wouldn't touch this genre for years to come, and the closest you could get on VCS and competing any-game consoles never stood a chance at reproducing this experience. Rosenthal's brief stint running Vectorbeam, a bright light of innovation and visual achievement in the industry, ended the same year this came out, all because Barrer bombed and its manufacturing costs fatally wounded the company. If they had found more market success and iterated on vector tech as fast as he'd introduced it, who knows if the Vectrex and similar projects might have fared better?

Today you can only play Speed Freak on a properly maintained real-life board or, thankfully, through MAME. It's a guilty pleasure of mine, easy to rebind for controllers and a neat subject for screenshots. Maybe the likes of Digital Eclipse, Night Dive, or another prestigious studio could figure out the licensing situation for these formative vector games and get all the experts in one room to make an Atari 50-caliber collection one day. Or maybe that window's passed, given how many industry people from the time have passed on or simply become unavailable. Give this a try regardless! It's simultaneously the start and end of an era, hiding in plain sight among its own kind.