text by tim rogers

★★★★

“HANDS-DOWN THE BEST 'JAPANESE RPG' OF ALL-TIME.”

In 1986, Enix’s Yuji Horii made Dragon Quest; in 1987, Squaresoft’s Hironobu Sakaguchi made Final Fantasy. Sakaguchi claimed to not have been inspired by Dragon Quest. The reason his game had turned out very similarly to Dragon Quest was because both Sakaguchi and Horii were mainly influenced by at-the-time unheard-of (in Japan) obsessions with the Ultima series of PC role-playing games and the Dungeons and Dragons tabletop, basement-bottom imagination-requiring adventures. Dragon Quest was to Ultima what Pac-Man was to Missile Command — a slimming reinterpretation that somehow managed to be both more mysterious and less vague. Final Fantasy was to Ultima as Super Mario Bros. was to Centipede — it’s more fun, more straightforward.

The two series grew up side-by-side, Final Fantasy continuing to dazzle and entertain (the sequel included a half-dozen vehicles for the player to ride, including big ostrich-like birds called Chocobos, a canoe, a boat, an ice-boat, and an airship), and Dragon Quest striving to perfect its original aims. At the outset of the 16-bit-era, Final Fantasy games had evolved to tell stories that involved hovercrafts, giant robots, and a trip to the moon; Dragon Quest, meanwhile, was all about telling simple little stories with simple, palm-sized gimmicks. The Super Famicom saw the two producers (and their talented teams) at the top of their games: Dragon Quest V, a casual, lighthearted yet affecting roman-fleuve, and Final Fantasy VI, a thrilling, operatic story spanning two eras of history and starring fourteen main characters. When it was announced that, for whatever miraculous reason, the two teams would work together on a game called Chrono Trigger, everyone who touched the issue of Weekly Famitsu carrying the exclusive preview literally and figuratively exploded.

This was in 1995, when just about anyone’s big brother or sister was reading Interview with a Vampire and writing in their diary about how they thought it would be so cool to be a vampire, too. Those of us who cared about videogames couldn’t have witnessed a more amazing alignment of the stars: the makers of the two hottest Japanese game series were teaming up (back then, that they would someday unite to form one super-corporation was kind of unthinkable) to produce the kind of game they were each individually good at, and it would be about time travel.

The Wikipedia article on Chrono Trigger can fill you in with all the details on the production of Chrono Trigger. Yuji Horii wrote the majority of the scenario before the production of the game began. The theme was to be “time travel”, which was simultaneously a simple, childish game concept, like something a six-year-old Catholic boy would include at the end of his nightly prayers (“Please God, let them make a videogame about time-travel”) and something infinitely more ambitious than anyone had previously ever attempted in RPG stories. Horii has admitted openly to being inspired by the story of an old American science-fiction TV series called “Time Tunnel”, though there’s an almost-certain hint of “Doctor Who” in the way the story flows from casual episodes to world-threatening chaos and back again. The tale begins when a young boy runs into a young girl (literally) at a fair; there’s a spark of friendship between them, and just when they’re getting to know one another, the boy’s machine-loving tomboy friend uses the girl in a demonstration of her teleporting device, which malfunctions and sends the girl into a mysterious vortex. The boy follows her unthinkingly, and finds her four hundred years in the past, where she’s been mistaken for the missing queen of the very kingdom that was celebrating its one-thousandth year in the boy and girl’s home time period. The boy ends up rescuing the missing queen, and subsequently the girl, though once he gets her back to the future, he’s arrested for having absconded with her.

There’s a virtuoso sequence here, involving a court trial and imprisonment of the main character. The game has ingeniously recorded the actions of the player at the fair, where you had an opportunity to steal and eat a man’s lunch or even make a kid cry. If you were nice, you can find a girl’s missing cat and score positive points with the jury. How well you do doesn’t matter in the end, though — you’re gonna get jailed. In a breathtaking use of fast zooms and side-angle shots, with an amazing swell of music, Chrono Trigger impresses the player with a feeling of dread: the main character is being led across a bridge, under an ominous moon, hands and legs shackled, by an evil man. Here, all of the tools of the “Japanese RPG” developer’s idea kit are being used simultaneously, transforming the game at once to the 1990s videogame equivalent of “Gone with the Wind”. The crucial pieces are all in place, both physically and emotionally — and though the player might have just endured the more subdued colors of an older world, and a boss battle in a possessed church, the terror of being wrongly accused and imprisoned, awaiting the death penalty, in one’s own time period really hammers something home. Of course, your friends are on hand to break you out of prison, and in the thrilling escape from the prison, your brainy friend notices a time gate, and uses a handy device she created to pop open the gate and escape into an unknown time period — which happens to be the barren, destroyed world of the year 2300 AD, where the last surviving humans huddle, starving, in dilapidated domed cities, kept alive only by a machine that rejuvenates their bodies while leaving their stomachs empty. A little bit of spelunking into the mutant-infested outskirts of a dead future city brings the party to a computer that, when activated, shows them the last record of the prosperous human civilization of 1999 AD: the day when a giant demonic alien parasite named Lavos burst out of the crust of the earth and rained napalm over all civilization. Having witnessed this catastrophe, the three friends swear to unlock the secrets of time travel and prevent the destruction of the world.

The one-two-three emotional punch of Chrono Trigger opening stages lays everything on the line. We have pleasant chumming and character-development at the Millennial Fair, we have quirky medieval time-traveling hijinks in 600 AD, we have the trial and conviction in the present, and then the revelation of the premature end of the world. The rest of the story sees the characters spanning seven crucial eras of world history, jumping all the way back to the year 65,000,000 BC to find a stone to repair the legendary sword Masamune, which must be wielded by a hero (now turned into a humanoid frog) to defeat an evil wizard named Magus, who they suspect is attempting to summon Lavos from the ether in the year 600. It turns out to all just be a wild goose chase — Magus isn’t really a bad guy; he’s summoning Lavos because he wants to kill the monster, to set right some tragedy that occurred in the past, and we realize we’ve just spent the past dozen hours of gameplay messing up his whole righteous plan.

The tale splits in wild directions from this point. It’s like a hit television series striding into its second season — new characters are introduced, old characters change, major overarching plot details rise slowly from the ashes. The wildest, most imaginative fragments of the game’s tale take place in the year 12,000 BC, at the height of an enlightened civilization, where a mysterious prophet intones warnings of armageddon to a vain queen set on building an enormous palace beneath the ocean — which will draw all of its electrical power from the sleeping parasite nested in the earth’s core. These script for these sequences was written by Masato Kato, the man who had been responsible for the invention of in-game cinematics in Tecmo’s Ninja Gaiden.

The developmental theme of Chrono Trigger, then, was “talent”. Something tells me it was all Yuji Horii’s idea — get talented people together under a unified purpose, let everyone do what they excel at, and then bundle the results up into a highly polished package. Masato Kato, for example, would go on to pen stories for Xenogears and Chrono Trigger‘s prodigal (as in, one day it will return to us, and we will see about actually loving it) sequel Chrono Cross, and he’d mostly pump out noisy nonsense, though in moderation — in Chrono Trigger — his talents sparkle.

Whether you like him or not, even Akira Toriyama shines in Chrono Trigger, and mostly by doing exactly what’s expected of him. The main character, Crono, is a reworking of his spiky-haired Son Goku stereotype, now given a samurai sword and a headband; the girl, Marle, is a cleaning-up of Bulma from Dragon Ball, now dressed in white; Lucca, with her big glasses and boyish haircut, is clearly a teenaged rebirthing of Arare-chan, the heroine of the manga that put Toriyama on the map, Doctor Slump. Frog is the typical Toriyama beastman oddity, vaguely familiar yet unlike anything he’s drawn before or since, and Frog’s nemesis Magus is a vampire-like, scythe-wielding, caped man with a widow’s peak and a chalky complexion. He might remind you of what Vegeta would look like if Dragon Ball had been influenced by Lord of the Rings instead of Journey to the West. Robo the robot (from the future) exhibits Toriyama’s thoughtful talent for making technology look like high fashion, and Ayla the cavewoman is, well, the token breasty blonde. It’s a hell of a mish-mashed collection of characters and caricatures, though Toriyama pulls it all of with exceptional grace.

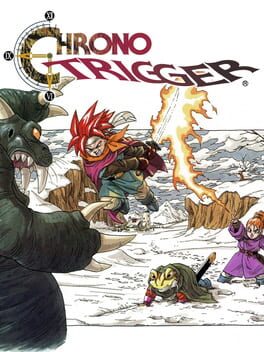

Chrono Trigger‘s art design is quite remarkable from a modern perspective, in this day and age where every Tales of… game that Namco cranks out opens with a fully animated cut-scene under music by a hot Japanese pop act: the Tales of… openings are always at least halfway lifeless, with the “camera” panning in front of stationary characters who change pose just as the pop song reaches a drum fill and the pan ends. Meanwhile, many years ago, Chrono Trigger was able to drop jaws and inspire daydreams with only poster-sized stationary images that are actually not featured anywhere in the game. Akira Toriyama’s massive talent — again, whether you like him or not — is scarcely more visible than in the promotional paintings he did of Chrono Trigger‘s characters in various dangerous situations. The sweep of the clouds, the etched lines of the landscapes, the throwaway details — everything good about Toriyama’s decades-long Dragon Ball series is captured in his Chrono Trigger scenes: a battle against Magus outside his castle in 600 AD, a scene with Lucca repairing Robo’s innards at her home in 1000 AD, the time machine Epoch soaring through the skies of 1999 AD, a battle in a mysterious coliseum, an epic battle of Crono, Marle, and Frog against a giant snow beast (which amazingly graced the American release’s cover art, even in the anime-fearing 1990s, when game publishers were usually inclined to commission some airbrushed Dungeons and Dragons stuff), and a virtuoso scene of the characters asleep around a campfire while curious monsters peek in from the trees. These out-game scenes, leaked into pop-culture through Japanese magazines, did more to establish the tone and wonder of the game than any in-game cut-scene or animated theme-song intro has ever done.

Yes, Chrono Trigger might just be the best-produced Japanese videogame of all time, where the word “produced” is taken at face value. Just two years after Chrono Trigger, we’d see Final Fantasy VII, and more than immediately (that is, well before the game was even released), the old guard was announced prematurely dead, and the world as we knew it grew obsessed with simplistic, manufactured angst, canned armageddon, fierce mathematics masquerading as “character customization”, and increasingly less blocky computer-animated full-motion video. Around this point, Hironobu Sakaguchi, no doubt shell-shocked from his wonderful experience helming Chrono Trigger, retreated from the world of videogames, and saw about directing a major motion picture.

Ten years have passed, and now Sakaguchi is back. And, perhaps ironically, his current vision has a lot in common with the conception of Chrono Trigger. Remembering that day and age when he and a team of talented, respected men assembled and instantly sold 2.3 million copies of a brand-new videogame franchise based on their names alone, Sakaguchi has sounded the call, and begun working on new legends — Blue Dragon and Lost Odyssey, both with characters by white-hot artists (Blue Dragon sees Toriyama reprising and dialing down his Chrono Trigger vibe; Lost Odyssey sees masterpiece-maker Takehiko Inoue’s original videogame debut), and one of them with a story by Kiyoshi Shigematsu, modern Japan’s equivalent of Gabriel Garcia-Marquez.

When one speaks of Chrono Trigger, the first names to crop up usually belong to artist Akira Toriyama, scenario-writer Yuji Horii, and music composer Yasunori Mitsuda. Though it was Sakaguchi’s gumption that made a videogame out of this glob of brain-ambrosia. High off of the — dare we say it — conscientious artistic success of Final Fantasy VI, Sakaguchi must have seen Chrono Trigger as the perfect opportunity to sharpen his pen. Final Fantasy VI‘s major stylistic achievement had occurred in virtuoso segments like the “Opera House”, where things are happening in the story — the beautiful female general Celes is impersonating an opera diva who a notorious gambler is slated to kidnap during the climax of her big performance, because the adventurers want to commandeer the gambler’s flying ship; meanwhile, a rogue octopus who hates our heroes for selfish reasons decides to sabotage Celes’ opera performance. As the unenthusiastic Celes, the player has to learn the lines of the opera, so as to sing convincingly; as the daring Locke, the player has to make his way around backstage, flipping the right switches to gain access to the rafters and take down the octopus so that the performance can go on. There’s a neat little twist ending to the whole fiasco. In the end, nearly every participating player was wowed. The “Opera House” scene, however, had just been an experiment, and one that required literally gallons of precious creative juices, so the rest of Final Fantasy VI (though not without its gems) was a tiny bit thin in comparison. In Chrono Trigger, few scenes stand out like the “Opera House” did in Final Fantasy VI, though we dare say that there’s not a single storyline event that isn’t more thrilling than anything event that’s occurred in any other RPG since. The raid on Magus’s castle in 600 AD is particularly amazing — though you barely do any more than walk down straight corridors, the planning is miraculous: mini-bosses pop out at just the right moments, and speak just enough dialogue before the fights to endear themselves as rounded characters. There’s a side-scrolling trek across parapets, an ominous descent down a dark, long staircase, during which the satanic chanting music builds in volume and intensity. Enter the door at the bottom of the stairs, and the chanting stops at once: silence. It’s not just an RPG dungeon — you’re not plunging into a crypt to dig up some magic mirror or something, you’re raiding a castle with the purpose of killing a guy, and the flawless presentation keeps you believing all the way up to the thrilling showdown and the cliffhanging revelation.

Future RPGs would tackle Chrono Trigger from the wrong angle — the game was, for better or for worse, the death knell of fantastic RPG dungeons. It birthed a tendency to keep everything straightforward and clean, with bosses popping up when needed. Xenosaga and Final Fantasy X pull the player forward through lifeless corridors laced with random battles and occasional boss battles prefaced by cute little dialogues. These games, however, are bloodless corpses when stood up beside Chrono Trigger, a miracle born of its creators’ attention and love, and of its tremendously tight, personality-fueled writing. (Note: if you’ve only played the English version, I assure you that the writing in the Japanese version is magnitudes smarter.)

Reviewers of the age praised Chrono Trigger for a multitude of reasons, including its fantastic plot, its multiple endings, and its great graphics. Electronic Gaming Monthly was sure, also, to praise the fact that its cartridge was 32 megabytes in size. Many critics semi-wrongly pumped their fists at the game’s method of presenting battles. Previous RPGs had faded to black occasionally and changed to a “battle screen” for each battle; Chrono Trigger, however, keeps all three characters visible on the screen at all times, and at specific points in dungeons (perhaps more accurately called “traveling sequences”), when enemies jump in from the sidelines, menus simply slide onto the screen and the characters draw their weapons; the battles then progress just as any pseudo-realtime battle in a Final Fantasy, now with a semi-pointless distance variable thrown into the mix. This wasn’t the “death” of the “random battle”, as many reviewers seemed to believe — it was just a conscientious workaround, a placeholder for something awesome — which would continue to elude RPG producers for the better half of a decade. For one thing, almost every battle in the game is unavoidable. Random battles, then, are most insulting because you can’t see the enemies before the battle begins — which I guess makes sense. Though hey, the typical RPG uses higher-quality character models during battle scenes than they use during field screens, meaning that the battles are deemed more important than the plot events by a majority of the games’ staffs. Really, has an RPG (not counting Dragon Quest, where your party members are usually invisible) ever had in-battle character models of lower graphical quality than the field models? I’m going to say no — maybe that’s the chief symptom of the RPG malaise: the developers find battling more important than adventuring, and it’s a weeping pity that, nine times out of ten, the battle systems in RPGs are just plain not exciting.

I might possibly review this game again someday, several times. It might even be useful to review it every time a new big RPG comes out. Maybe I’ll play that big new RPG, be thoroughly disappointed by it, and then replay Chrono Trigger, and review Chrono Trigger again, based on what the new game did wrong. One might say that this review is a counterpoint to my Blue Dragon review, where I score the game pretty highly; after playing Blue Dragon, I played Chrono Trigger again, and Blue Dragon is actually quite bland in comparison — though not as bland as, say, Final Fantasy X. All Blue Dragon lacks, when compared to Chrono Trigger, is smoother battle transitions and a rock-solid, palm-sized story gimmick. (Like, say, time travel–no, that’s been taken.) Compared to Chrono Trigger, Dragon Quest Swords lacks dramatic weight in its action stages as well as the rock-solid, compelling story gimmick and exceptional writing.

Most pointedly, replaying Chrono Trigger again for the purposes of this review made me remember Hironobu Sakaguchi’s recent declaration of love for Epic Games’ shooter Gears of War. In Gears of War‘s campaign mode, I couldn’t help remembering Chrono Trigger when, around every shattered city block, enemy gunfire rained from the sky and my men swore aloud, shouted orders, and scattered to find cover. What’s that, if not a RPG battle transition? Are we not “playing” a “role” in Gears of War, anyway? Sakaguchi is a man of love, life, and details, and Chrono Trigger is the best project he’s ever been involved with. (It’s the best project that anyone involved with it has ever been involved with, in fact.) Surely, the battle presentation was a revolution waiting to happen; what if they would have thought a little harder, though? What if they would have incorporated a Secret of Mana-style action-packed, button-jabbing battle system? I’m sure Sakaguchi didn’t do it because Secret of Mana felt too thin. What about a crispy, poppy, 16-bit Zelda-like battle system, with simple, pleasant guarding and item management? No, he’d wanted each battle to have a kind of dramatic weight — a Zelda flow would have made the game feel too loose in comparison to an actual Zelda title, and there wasn’t enough staff to bring everything up to speed. Over a decade later, Gears of War must have been a tremendous revelation: maybe it’s possible, now, to stage intriguing, cinema-worthy battles of spectacle during straightforward trudges through fascinating surroundings. That Gears of War recycles and reuses the same three play mechanics (take cover, fire guns, throw grenades into emergence holes) a million times without ever feeling old should be a wonder to anyone who’s ever slogged through a Tales of… game.

I always ask, these days — what if someone were to take the Gundam story that has fascinated generations of Japanese manboys and give it a full, loving RPG treatment, complete with towns and atmosphere, customization, animated cut-scenes and an enthralling, action-packed battle system? I know this won’t happen because game companies don’t want to set the bar higher than they’re willing to jump. Why haven’t any Neon Genesis Evangelion games — ever — allowed the player to control a giant robot? Why are they all alternate-universe high school love stories, or detective murder mysteries, or sequels to alternate-universe high school love stories, or pachinko-slot-machine simulators? In the late 1990s, Neon Genesis Evangelion and Final Fantasy VII gangbanged the Japanese RPG format from opposite, grisly angles, and the developers have been auto-erotic asphyxiating themselves with ropes made of money ever since.

It’s amazing, in this light, that Chrono Trigger ever got made. The amount of creativity and balls that went into its production is just about unthinkable in the present climate. The story is as lovingly presented and conceived as an entire four-season sci-fi television series, the characters are as endearing as anything ever put into a classic Japanese animated series, the ingenious multiple endings and “New Game +” mode keep the fan-service close to the game’s heart, and the music of Yasunori Mitsuda is studded with innumerable gems as evocative of Ryuichi Sakamoto as of Rick Astley (see here), all equal parts three-minute-pop-song, new-age experiment, and classic videogame BGM. Future games would try to disassemble Chrono Trigger‘s winning formula and sell it piece by piece, which makes a lot of sense when one considers that yes, videogames are a commodity. Though it really is kind of sad, when you go back and play Chrono Trigger again, and witness how obscenely together it is, and wonder why no one ever summoned the conscience required to tighten up its noble ambitions. Here’s to Dragon Quest X, then, and to whatever Sakaguchi’s planning for after Lost Odyssey, and to White Knight Story. The kid deep inside us, who grew up in the 1980s watching reruns of 1970s Japanese animations about plucky boys somehow outsmarting grave fates will live again — we look forward to how.

★★★★

“HANDS-DOWN THE BEST 'JAPANESE RPG' OF ALL-TIME.”

In 1986, Enix’s Yuji Horii made Dragon Quest; in 1987, Squaresoft’s Hironobu Sakaguchi made Final Fantasy. Sakaguchi claimed to not have been inspired by Dragon Quest. The reason his game had turned out very similarly to Dragon Quest was because both Sakaguchi and Horii were mainly influenced by at-the-time unheard-of (in Japan) obsessions with the Ultima series of PC role-playing games and the Dungeons and Dragons tabletop, basement-bottom imagination-requiring adventures. Dragon Quest was to Ultima what Pac-Man was to Missile Command — a slimming reinterpretation that somehow managed to be both more mysterious and less vague. Final Fantasy was to Ultima as Super Mario Bros. was to Centipede — it’s more fun, more straightforward.

The two series grew up side-by-side, Final Fantasy continuing to dazzle and entertain (the sequel included a half-dozen vehicles for the player to ride, including big ostrich-like birds called Chocobos, a canoe, a boat, an ice-boat, and an airship), and Dragon Quest striving to perfect its original aims. At the outset of the 16-bit-era, Final Fantasy games had evolved to tell stories that involved hovercrafts, giant robots, and a trip to the moon; Dragon Quest, meanwhile, was all about telling simple little stories with simple, palm-sized gimmicks. The Super Famicom saw the two producers (and their talented teams) at the top of their games: Dragon Quest V, a casual, lighthearted yet affecting roman-fleuve, and Final Fantasy VI, a thrilling, operatic story spanning two eras of history and starring fourteen main characters. When it was announced that, for whatever miraculous reason, the two teams would work together on a game called Chrono Trigger, everyone who touched the issue of Weekly Famitsu carrying the exclusive preview literally and figuratively exploded.

This was in 1995, when just about anyone’s big brother or sister was reading Interview with a Vampire and writing in their diary about how they thought it would be so cool to be a vampire, too. Those of us who cared about videogames couldn’t have witnessed a more amazing alignment of the stars: the makers of the two hottest Japanese game series were teaming up (back then, that they would someday unite to form one super-corporation was kind of unthinkable) to produce the kind of game they were each individually good at, and it would be about time travel.

The Wikipedia article on Chrono Trigger can fill you in with all the details on the production of Chrono Trigger. Yuji Horii wrote the majority of the scenario before the production of the game began. The theme was to be “time travel”, which was simultaneously a simple, childish game concept, like something a six-year-old Catholic boy would include at the end of his nightly prayers (“Please God, let them make a videogame about time-travel”) and something infinitely more ambitious than anyone had previously ever attempted in RPG stories. Horii has admitted openly to being inspired by the story of an old American science-fiction TV series called “Time Tunnel”, though there’s an almost-certain hint of “Doctor Who” in the way the story flows from casual episodes to world-threatening chaos and back again. The tale begins when a young boy runs into a young girl (literally) at a fair; there’s a spark of friendship between them, and just when they’re getting to know one another, the boy’s machine-loving tomboy friend uses the girl in a demonstration of her teleporting device, which malfunctions and sends the girl into a mysterious vortex. The boy follows her unthinkingly, and finds her four hundred years in the past, where she’s been mistaken for the missing queen of the very kingdom that was celebrating its one-thousandth year in the boy and girl’s home time period. The boy ends up rescuing the missing queen, and subsequently the girl, though once he gets her back to the future, he’s arrested for having absconded with her.

There’s a virtuoso sequence here, involving a court trial and imprisonment of the main character. The game has ingeniously recorded the actions of the player at the fair, where you had an opportunity to steal and eat a man’s lunch or even make a kid cry. If you were nice, you can find a girl’s missing cat and score positive points with the jury. How well you do doesn’t matter in the end, though — you’re gonna get jailed. In a breathtaking use of fast zooms and side-angle shots, with an amazing swell of music, Chrono Trigger impresses the player with a feeling of dread: the main character is being led across a bridge, under an ominous moon, hands and legs shackled, by an evil man. Here, all of the tools of the “Japanese RPG” developer’s idea kit are being used simultaneously, transforming the game at once to the 1990s videogame equivalent of “Gone with the Wind”. The crucial pieces are all in place, both physically and emotionally — and though the player might have just endured the more subdued colors of an older world, and a boss battle in a possessed church, the terror of being wrongly accused and imprisoned, awaiting the death penalty, in one’s own time period really hammers something home. Of course, your friends are on hand to break you out of prison, and in the thrilling escape from the prison, your brainy friend notices a time gate, and uses a handy device she created to pop open the gate and escape into an unknown time period — which happens to be the barren, destroyed world of the year 2300 AD, where the last surviving humans huddle, starving, in dilapidated domed cities, kept alive only by a machine that rejuvenates their bodies while leaving their stomachs empty. A little bit of spelunking into the mutant-infested outskirts of a dead future city brings the party to a computer that, when activated, shows them the last record of the prosperous human civilization of 1999 AD: the day when a giant demonic alien parasite named Lavos burst out of the crust of the earth and rained napalm over all civilization. Having witnessed this catastrophe, the three friends swear to unlock the secrets of time travel and prevent the destruction of the world.

The one-two-three emotional punch of Chrono Trigger opening stages lays everything on the line. We have pleasant chumming and character-development at the Millennial Fair, we have quirky medieval time-traveling hijinks in 600 AD, we have the trial and conviction in the present, and then the revelation of the premature end of the world. The rest of the story sees the characters spanning seven crucial eras of world history, jumping all the way back to the year 65,000,000 BC to find a stone to repair the legendary sword Masamune, which must be wielded by a hero (now turned into a humanoid frog) to defeat an evil wizard named Magus, who they suspect is attempting to summon Lavos from the ether in the year 600. It turns out to all just be a wild goose chase — Magus isn’t really a bad guy; he’s summoning Lavos because he wants to kill the monster, to set right some tragedy that occurred in the past, and we realize we’ve just spent the past dozen hours of gameplay messing up his whole righteous plan.

The tale splits in wild directions from this point. It’s like a hit television series striding into its second season — new characters are introduced, old characters change, major overarching plot details rise slowly from the ashes. The wildest, most imaginative fragments of the game’s tale take place in the year 12,000 BC, at the height of an enlightened civilization, where a mysterious prophet intones warnings of armageddon to a vain queen set on building an enormous palace beneath the ocean — which will draw all of its electrical power from the sleeping parasite nested in the earth’s core. These script for these sequences was written by Masato Kato, the man who had been responsible for the invention of in-game cinematics in Tecmo’s Ninja Gaiden.

The developmental theme of Chrono Trigger, then, was “talent”. Something tells me it was all Yuji Horii’s idea — get talented people together under a unified purpose, let everyone do what they excel at, and then bundle the results up into a highly polished package. Masato Kato, for example, would go on to pen stories for Xenogears and Chrono Trigger‘s prodigal (as in, one day it will return to us, and we will see about actually loving it) sequel Chrono Cross, and he’d mostly pump out noisy nonsense, though in moderation — in Chrono Trigger — his talents sparkle.

Whether you like him or not, even Akira Toriyama shines in Chrono Trigger, and mostly by doing exactly what’s expected of him. The main character, Crono, is a reworking of his spiky-haired Son Goku stereotype, now given a samurai sword and a headband; the girl, Marle, is a cleaning-up of Bulma from Dragon Ball, now dressed in white; Lucca, with her big glasses and boyish haircut, is clearly a teenaged rebirthing of Arare-chan, the heroine of the manga that put Toriyama on the map, Doctor Slump. Frog is the typical Toriyama beastman oddity, vaguely familiar yet unlike anything he’s drawn before or since, and Frog’s nemesis Magus is a vampire-like, scythe-wielding, caped man with a widow’s peak and a chalky complexion. He might remind you of what Vegeta would look like if Dragon Ball had been influenced by Lord of the Rings instead of Journey to the West. Robo the robot (from the future) exhibits Toriyama’s thoughtful talent for making technology look like high fashion, and Ayla the cavewoman is, well, the token breasty blonde. It’s a hell of a mish-mashed collection of characters and caricatures, though Toriyama pulls it all of with exceptional grace.

Chrono Trigger‘s art design is quite remarkable from a modern perspective, in this day and age where every Tales of… game that Namco cranks out opens with a fully animated cut-scene under music by a hot Japanese pop act: the Tales of… openings are always at least halfway lifeless, with the “camera” panning in front of stationary characters who change pose just as the pop song reaches a drum fill and the pan ends. Meanwhile, many years ago, Chrono Trigger was able to drop jaws and inspire daydreams with only poster-sized stationary images that are actually not featured anywhere in the game. Akira Toriyama’s massive talent — again, whether you like him or not — is scarcely more visible than in the promotional paintings he did of Chrono Trigger‘s characters in various dangerous situations. The sweep of the clouds, the etched lines of the landscapes, the throwaway details — everything good about Toriyama’s decades-long Dragon Ball series is captured in his Chrono Trigger scenes: a battle against Magus outside his castle in 600 AD, a scene with Lucca repairing Robo’s innards at her home in 1000 AD, the time machine Epoch soaring through the skies of 1999 AD, a battle in a mysterious coliseum, an epic battle of Crono, Marle, and Frog against a giant snow beast (which amazingly graced the American release’s cover art, even in the anime-fearing 1990s, when game publishers were usually inclined to commission some airbrushed Dungeons and Dragons stuff), and a virtuoso scene of the characters asleep around a campfire while curious monsters peek in from the trees. These out-game scenes, leaked into pop-culture through Japanese magazines, did more to establish the tone and wonder of the game than any in-game cut-scene or animated theme-song intro has ever done.

Yes, Chrono Trigger might just be the best-produced Japanese videogame of all time, where the word “produced” is taken at face value. Just two years after Chrono Trigger, we’d see Final Fantasy VII, and more than immediately (that is, well before the game was even released), the old guard was announced prematurely dead, and the world as we knew it grew obsessed with simplistic, manufactured angst, canned armageddon, fierce mathematics masquerading as “character customization”, and increasingly less blocky computer-animated full-motion video. Around this point, Hironobu Sakaguchi, no doubt shell-shocked from his wonderful experience helming Chrono Trigger, retreated from the world of videogames, and saw about directing a major motion picture.

Ten years have passed, and now Sakaguchi is back. And, perhaps ironically, his current vision has a lot in common with the conception of Chrono Trigger. Remembering that day and age when he and a team of talented, respected men assembled and instantly sold 2.3 million copies of a brand-new videogame franchise based on their names alone, Sakaguchi has sounded the call, and begun working on new legends — Blue Dragon and Lost Odyssey, both with characters by white-hot artists (Blue Dragon sees Toriyama reprising and dialing down his Chrono Trigger vibe; Lost Odyssey sees masterpiece-maker Takehiko Inoue’s original videogame debut), and one of them with a story by Kiyoshi Shigematsu, modern Japan’s equivalent of Gabriel Garcia-Marquez.

When one speaks of Chrono Trigger, the first names to crop up usually belong to artist Akira Toriyama, scenario-writer Yuji Horii, and music composer Yasunori Mitsuda. Though it was Sakaguchi’s gumption that made a videogame out of this glob of brain-ambrosia. High off of the — dare we say it — conscientious artistic success of Final Fantasy VI, Sakaguchi must have seen Chrono Trigger as the perfect opportunity to sharpen his pen. Final Fantasy VI‘s major stylistic achievement had occurred in virtuoso segments like the “Opera House”, where things are happening in the story — the beautiful female general Celes is impersonating an opera diva who a notorious gambler is slated to kidnap during the climax of her big performance, because the adventurers want to commandeer the gambler’s flying ship; meanwhile, a rogue octopus who hates our heroes for selfish reasons decides to sabotage Celes’ opera performance. As the unenthusiastic Celes, the player has to learn the lines of the opera, so as to sing convincingly; as the daring Locke, the player has to make his way around backstage, flipping the right switches to gain access to the rafters and take down the octopus so that the performance can go on. There’s a neat little twist ending to the whole fiasco. In the end, nearly every participating player was wowed. The “Opera House” scene, however, had just been an experiment, and one that required literally gallons of precious creative juices, so the rest of Final Fantasy VI (though not without its gems) was a tiny bit thin in comparison. In Chrono Trigger, few scenes stand out like the “Opera House” did in Final Fantasy VI, though we dare say that there’s not a single storyline event that isn’t more thrilling than anything event that’s occurred in any other RPG since. The raid on Magus’s castle in 600 AD is particularly amazing — though you barely do any more than walk down straight corridors, the planning is miraculous: mini-bosses pop out at just the right moments, and speak just enough dialogue before the fights to endear themselves as rounded characters. There’s a side-scrolling trek across parapets, an ominous descent down a dark, long staircase, during which the satanic chanting music builds in volume and intensity. Enter the door at the bottom of the stairs, and the chanting stops at once: silence. It’s not just an RPG dungeon — you’re not plunging into a crypt to dig up some magic mirror or something, you’re raiding a castle with the purpose of killing a guy, and the flawless presentation keeps you believing all the way up to the thrilling showdown and the cliffhanging revelation.

Future RPGs would tackle Chrono Trigger from the wrong angle — the game was, for better or for worse, the death knell of fantastic RPG dungeons. It birthed a tendency to keep everything straightforward and clean, with bosses popping up when needed. Xenosaga and Final Fantasy X pull the player forward through lifeless corridors laced with random battles and occasional boss battles prefaced by cute little dialogues. These games, however, are bloodless corpses when stood up beside Chrono Trigger, a miracle born of its creators’ attention and love, and of its tremendously tight, personality-fueled writing. (Note: if you’ve only played the English version, I assure you that the writing in the Japanese version is magnitudes smarter.)

Reviewers of the age praised Chrono Trigger for a multitude of reasons, including its fantastic plot, its multiple endings, and its great graphics. Electronic Gaming Monthly was sure, also, to praise the fact that its cartridge was 32 megabytes in size. Many critics semi-wrongly pumped their fists at the game’s method of presenting battles. Previous RPGs had faded to black occasionally and changed to a “battle screen” for each battle; Chrono Trigger, however, keeps all three characters visible on the screen at all times, and at specific points in dungeons (perhaps more accurately called “traveling sequences”), when enemies jump in from the sidelines, menus simply slide onto the screen and the characters draw their weapons; the battles then progress just as any pseudo-realtime battle in a Final Fantasy, now with a semi-pointless distance variable thrown into the mix. This wasn’t the “death” of the “random battle”, as many reviewers seemed to believe — it was just a conscientious workaround, a placeholder for something awesome — which would continue to elude RPG producers for the better half of a decade. For one thing, almost every battle in the game is unavoidable. Random battles, then, are most insulting because you can’t see the enemies before the battle begins — which I guess makes sense. Though hey, the typical RPG uses higher-quality character models during battle scenes than they use during field screens, meaning that the battles are deemed more important than the plot events by a majority of the games’ staffs. Really, has an RPG (not counting Dragon Quest, where your party members are usually invisible) ever had in-battle character models of lower graphical quality than the field models? I’m going to say no — maybe that’s the chief symptom of the RPG malaise: the developers find battling more important than adventuring, and it’s a weeping pity that, nine times out of ten, the battle systems in RPGs are just plain not exciting.

I might possibly review this game again someday, several times. It might even be useful to review it every time a new big RPG comes out. Maybe I’ll play that big new RPG, be thoroughly disappointed by it, and then replay Chrono Trigger, and review Chrono Trigger again, based on what the new game did wrong. One might say that this review is a counterpoint to my Blue Dragon review, where I score the game pretty highly; after playing Blue Dragon, I played Chrono Trigger again, and Blue Dragon is actually quite bland in comparison — though not as bland as, say, Final Fantasy X. All Blue Dragon lacks, when compared to Chrono Trigger, is smoother battle transitions and a rock-solid, palm-sized story gimmick. (Like, say, time travel–no, that’s been taken.) Compared to Chrono Trigger, Dragon Quest Swords lacks dramatic weight in its action stages as well as the rock-solid, compelling story gimmick and exceptional writing.

Most pointedly, replaying Chrono Trigger again for the purposes of this review made me remember Hironobu Sakaguchi’s recent declaration of love for Epic Games’ shooter Gears of War. In Gears of War‘s campaign mode, I couldn’t help remembering Chrono Trigger when, around every shattered city block, enemy gunfire rained from the sky and my men swore aloud, shouted orders, and scattered to find cover. What’s that, if not a RPG battle transition? Are we not “playing” a “role” in Gears of War, anyway? Sakaguchi is a man of love, life, and details, and Chrono Trigger is the best project he’s ever been involved with. (It’s the best project that anyone involved with it has ever been involved with, in fact.) Surely, the battle presentation was a revolution waiting to happen; what if they would have thought a little harder, though? What if they would have incorporated a Secret of Mana-style action-packed, button-jabbing battle system? I’m sure Sakaguchi didn’t do it because Secret of Mana felt too thin. What about a crispy, poppy, 16-bit Zelda-like battle system, with simple, pleasant guarding and item management? No, he’d wanted each battle to have a kind of dramatic weight — a Zelda flow would have made the game feel too loose in comparison to an actual Zelda title, and there wasn’t enough staff to bring everything up to speed. Over a decade later, Gears of War must have been a tremendous revelation: maybe it’s possible, now, to stage intriguing, cinema-worthy battles of spectacle during straightforward trudges through fascinating surroundings. That Gears of War recycles and reuses the same three play mechanics (take cover, fire guns, throw grenades into emergence holes) a million times without ever feeling old should be a wonder to anyone who’s ever slogged through a Tales of… game.

I always ask, these days — what if someone were to take the Gundam story that has fascinated generations of Japanese manboys and give it a full, loving RPG treatment, complete with towns and atmosphere, customization, animated cut-scenes and an enthralling, action-packed battle system? I know this won’t happen because game companies don’t want to set the bar higher than they’re willing to jump. Why haven’t any Neon Genesis Evangelion games — ever — allowed the player to control a giant robot? Why are they all alternate-universe high school love stories, or detective murder mysteries, or sequels to alternate-universe high school love stories, or pachinko-slot-machine simulators? In the late 1990s, Neon Genesis Evangelion and Final Fantasy VII gangbanged the Japanese RPG format from opposite, grisly angles, and the developers have been auto-erotic asphyxiating themselves with ropes made of money ever since.

It’s amazing, in this light, that Chrono Trigger ever got made. The amount of creativity and balls that went into its production is just about unthinkable in the present climate. The story is as lovingly presented and conceived as an entire four-season sci-fi television series, the characters are as endearing as anything ever put into a classic Japanese animated series, the ingenious multiple endings and “New Game +” mode keep the fan-service close to the game’s heart, and the music of Yasunori Mitsuda is studded with innumerable gems as evocative of Ryuichi Sakamoto as of Rick Astley (see here), all equal parts three-minute-pop-song, new-age experiment, and classic videogame BGM. Future games would try to disassemble Chrono Trigger‘s winning formula and sell it piece by piece, which makes a lot of sense when one considers that yes, videogames are a commodity. Though it really is kind of sad, when you go back and play Chrono Trigger again, and witness how obscenely together it is, and wonder why no one ever summoned the conscience required to tighten up its noble ambitions. Here’s to Dragon Quest X, then, and to whatever Sakaguchi’s planning for after Lost Odyssey, and to White Knight Story. The kid deep inside us, who grew up in the 1980s watching reruns of 1970s Japanese animations about plucky boys somehow outsmarting grave fates will live again — we look forward to how.