'There was an old Man of the Hague, whose ideas were excessively vague; he built a balloon, to examine the moon, that deluded Old Man of the Hague.'

– Edward Lear, A Book of Nonsense, 1846.

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (22nd Aug. – 28th Aug., 2023).

After his cycles of paintings on family and parties, dedicated to the study of interpersonal relationships, Michael Andrew spent several years developing a very refined meditation on the theme of air. He called this series 'Lights', which consists of a series of landscapes over which a hot air balloon flies. It hovers over the English countryside, over a river, through a city lit by the glow of the night, and so many other places before finally arriving at the sea. Lights VII: A Shadow (1974) is an ecstatic, dizzying work. The composition is divided between the sand, the sea and the sky, while the green shadow of the balloon stretches across the lower part of the canvas. Andrew's use of acrylics renders this landscape seemingly abstract, making it look sunburnt, like an old photograph.

For Andrew, the balloon represents the ego, and each painting is a way of pursuing inner meditation through exposure to the sensory world: 'the balloon was a metaphor for the self as it dispenses with the ego, gradually attaining spiritual enlightenment in the process. The balloon is thus present in the first three paintings in the cycle but absent from the next three. In the seventh and last painting only its shadow is represented' [1]. Andrew's contemplation is rooted in his singular relationship with the world, steeped in Zen philosophy and fascinated by the scientific advances of the twentieth century. To some extent, his 'Lights' series retains some of the realist features of his formative years.

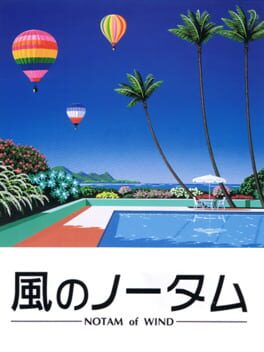

Detchibe has explored the ways in which Hiroshi Nagai's work shapes a situated perception of the 1980s: it is necessary to correlate these ideas with the declinist discourse that haunted the Lost Decades following the collapse of the Japanese economic bubble at the end of the 1980s. Gradually, the positive valence attached to companies and work was eroded by at least three factors perceived by Japanese society and highlighted by the media: a relaxation of labour laws that allowed companies to employ part-time workers, leading to a sense of 'unemployment within the company' (shanai shitsugyo); critical difficulties for young people to enter the labour market; and the collapse of the myth of social equality with the disappearance of the middle class of office workers [2]. This frustration was clearly expressed by Artdink with the release of Aquanaut no Kyūjitsu (1995), which follows a burnt-out oceanographer who tries to reconnect with the environment by exploring the sea with a deliberately meditative approach.

Kaze no NOTAM also suggests a return to a certain serenity, but with a focus on contemplation rather than exploration. The player is invited to fly over different environments at different times of day, accompanied by a soundtrack that echoes the city-pop aesthetic that was in decline at the time. Kaze no NOTAM recontextualises inactivity, turning it into an opportunity for introspection, as the balloon is subject to the uncertainties of air currents, without the possibility of changing its course in detail. For workers, the unemployed or young people at a loss for meaning, the title suggests taking the time to question the reasons for existence and the value of time, conjuring up an optimistic view of a golden age recently lost: the only thing that counts is the present. Among the most striking moments in Kaze no NOTAM are some breathtaking vistas. Flying over a canopy bathed in the rays of the sinking sun has a special magic, as does seeing the northern lights overhanging the long skyscrapers in the glittering city heavens.

Like Andrew's 'Lights' series, the game offers semi-abstract scenes thanks to the sharp PS1 edges of the topography: the title leaves it to the player's imagination to fill in the picture. The variety of environments also allows for a real progression in the meditation exercise. It is surprising, however, that Kaze no NOTAM places such a strong emphasis on objectives; while Aquanaut no Kyūjitsu involved building a coral reef, finding artefacts was an underlying product of the organic exploration of the seabed. In Kaze no NOTAM, the mere selection of an objective in the main menu distorts the idea of an unfettered meditation, especially when certain modes impose a time limit. The player can, of course, ignore these targets – after all, the point is simply to fly. As Andrew, eternal dreamer of another world, noted when he borrowed a Rosalie Sorrels song for a tentative title of his paintings, Up Is A Nice Place To Be (1967), 'the best' even [3].

__________

[1] Richard Calvocoressi, 'Michael Andrews: Air', in Gagosian Quaterly, Spring 2017.

[2] Andrew Gordon, 'Making sense of the lost decades: Workplaces and schools, men and women, young and old, rich and poor', in Yoichi Funabashi, Barak Kushner (ed.), Examining Japan's Lost Decades, Routledge, London, 2015, pp. 77-100.

[3] Richard Calvocoressi, op. cit.

– Edward Lear, A Book of Nonsense, 1846.

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (22nd Aug. – 28th Aug., 2023).

After his cycles of paintings on family and parties, dedicated to the study of interpersonal relationships, Michael Andrew spent several years developing a very refined meditation on the theme of air. He called this series 'Lights', which consists of a series of landscapes over which a hot air balloon flies. It hovers over the English countryside, over a river, through a city lit by the glow of the night, and so many other places before finally arriving at the sea. Lights VII: A Shadow (1974) is an ecstatic, dizzying work. The composition is divided between the sand, the sea and the sky, while the green shadow of the balloon stretches across the lower part of the canvas. Andrew's use of acrylics renders this landscape seemingly abstract, making it look sunburnt, like an old photograph.

For Andrew, the balloon represents the ego, and each painting is a way of pursuing inner meditation through exposure to the sensory world: 'the balloon was a metaphor for the self as it dispenses with the ego, gradually attaining spiritual enlightenment in the process. The balloon is thus present in the first three paintings in the cycle but absent from the next three. In the seventh and last painting only its shadow is represented' [1]. Andrew's contemplation is rooted in his singular relationship with the world, steeped in Zen philosophy and fascinated by the scientific advances of the twentieth century. To some extent, his 'Lights' series retains some of the realist features of his formative years.

Detchibe has explored the ways in which Hiroshi Nagai's work shapes a situated perception of the 1980s: it is necessary to correlate these ideas with the declinist discourse that haunted the Lost Decades following the collapse of the Japanese economic bubble at the end of the 1980s. Gradually, the positive valence attached to companies and work was eroded by at least three factors perceived by Japanese society and highlighted by the media: a relaxation of labour laws that allowed companies to employ part-time workers, leading to a sense of 'unemployment within the company' (shanai shitsugyo); critical difficulties for young people to enter the labour market; and the collapse of the myth of social equality with the disappearance of the middle class of office workers [2]. This frustration was clearly expressed by Artdink with the release of Aquanaut no Kyūjitsu (1995), which follows a burnt-out oceanographer who tries to reconnect with the environment by exploring the sea with a deliberately meditative approach.

Kaze no NOTAM also suggests a return to a certain serenity, but with a focus on contemplation rather than exploration. The player is invited to fly over different environments at different times of day, accompanied by a soundtrack that echoes the city-pop aesthetic that was in decline at the time. Kaze no NOTAM recontextualises inactivity, turning it into an opportunity for introspection, as the balloon is subject to the uncertainties of air currents, without the possibility of changing its course in detail. For workers, the unemployed or young people at a loss for meaning, the title suggests taking the time to question the reasons for existence and the value of time, conjuring up an optimistic view of a golden age recently lost: the only thing that counts is the present. Among the most striking moments in Kaze no NOTAM are some breathtaking vistas. Flying over a canopy bathed in the rays of the sinking sun has a special magic, as does seeing the northern lights overhanging the long skyscrapers in the glittering city heavens.

Like Andrew's 'Lights' series, the game offers semi-abstract scenes thanks to the sharp PS1 edges of the topography: the title leaves it to the player's imagination to fill in the picture. The variety of environments also allows for a real progression in the meditation exercise. It is surprising, however, that Kaze no NOTAM places such a strong emphasis on objectives; while Aquanaut no Kyūjitsu involved building a coral reef, finding artefacts was an underlying product of the organic exploration of the seabed. In Kaze no NOTAM, the mere selection of an objective in the main menu distorts the idea of an unfettered meditation, especially when certain modes impose a time limit. The player can, of course, ignore these targets – after all, the point is simply to fly. As Andrew, eternal dreamer of another world, noted when he borrowed a Rosalie Sorrels song for a tentative title of his paintings, Up Is A Nice Place To Be (1967), 'the best' even [3].

__________

[1] Richard Calvocoressi, 'Michael Andrews: Air', in Gagosian Quaterly, Spring 2017.

[2] Andrew Gordon, 'Making sense of the lost decades: Workplaces and schools, men and women, young and old, rich and poor', in Yoichi Funabashi, Barak Kushner (ed.), Examining Japan's Lost Decades, Routledge, London, 2015, pp. 77-100.

[3] Richard Calvocoressi, op. cit.