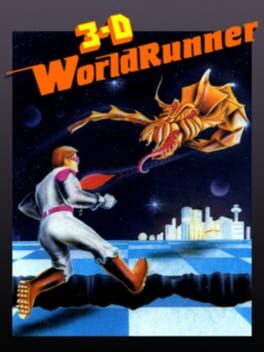

In 1986, Square was still in its infancy – the revelation of Final Fantasy (1987) had not yet taken place. Sakaguchi and Uematsu were not the key figures that the public knows so well today. This was not the case for Nasir Gebelli, who enjoyed a special aura at the time, thanks to the games he had published before the video game crash. Released on the Apple II, his titles were generally commercially successful, although some of them received a cooler reception. In any case, Gebelli had proven himself to be an ingenious programmer, capable of many technical feats. In particular, it is his use of 3D that impresses. This was implemented in Horizon V (1982) and especially Zenith (1982). For various reasons, economic and personal, Gebelli went to Japan, after the collapse of the video game industry. There he met Masafumi Miyamoto, the founder of Square, who recruited him. To mark the transition from microcomputers to the NES, he was asked to put forward his skills in stereoscopic 3D. The first game he programmed for Square was thus Tobidase Daisakusen.

The title is a kind of auto-runner with a camera behind the avatar. It puts us in the shoes of a soldier who has to stop an alien invasion. The game is not strictly speaking a rail shooter, as the protagonist cannot shoot for most of the game. Indeed, the gameplay focuses on jumping and dodging, which can be modulated with the D-pad to correct our speed. Only by retrieving a missile can we shoot – once – to get rid of an annoying enemy. In reality, the game's high speed and the very precise jumps that are sometimes required – for example, several successive bounces on fire pillars – invite the player to focus more on their movements, especially since the majority of enemies can be dodged without too much difficulty. The traps come from other elements. Firstly, the timer is sometimes quite cruel, requiring aggressive execution and punishing slow gameplay. Secondly, the Hand Men can block all movement on a section of the plane, forcing rather abrupt lateral movements, which can easily deceive the player. Finally, the visibility on the chasms is not exceptional, so it is easy to misjudge their length: it is common to make a jump that is too short or too long. This would be immediately be punished, since there is no possibility to slow down once in the air.

In terms of game design, the title is thus rather formal and sometimes a little too cruel for its own good. Jumping on the pillars is trivial, once you've bounced off the top of one, but getting there is another story. The game sometimes changes the running speed, which fools muscle memory. Some of the collisions are quite strange and having to bump into pillars to find possible tiems is a clunky system. On the other hand, the stereoscopic 3D is rather successful and the game exploits it well during boss fights, where the title turns into a shooter. The character evolves exclusively on a frontal plane and it is a matter of bombarding the snake with missiles, knowing that it is moving in a 3D environment. It oscillates between the background and the space behind the player, so it essential to anticipate its position, in order to maximize the damage done. In this context, stereoscopic 3D is a good addition, because it makes it really easy to determine whether the boss is in front or behind you. Beyond these sequences, the 3D is marginally useful. In the running sections, the size of the sprites is enough to indicate distances and the 3D, although immersive, seems superfluous. 3-D WorldRunner was never successful, but it was more of a technical showcase, intended to test Gebelli's programming skills. In this respect, the game has achieved its purpose.

The title is a kind of auto-runner with a camera behind the avatar. It puts us in the shoes of a soldier who has to stop an alien invasion. The game is not strictly speaking a rail shooter, as the protagonist cannot shoot for most of the game. Indeed, the gameplay focuses on jumping and dodging, which can be modulated with the D-pad to correct our speed. Only by retrieving a missile can we shoot – once – to get rid of an annoying enemy. In reality, the game's high speed and the very precise jumps that are sometimes required – for example, several successive bounces on fire pillars – invite the player to focus more on their movements, especially since the majority of enemies can be dodged without too much difficulty. The traps come from other elements. Firstly, the timer is sometimes quite cruel, requiring aggressive execution and punishing slow gameplay. Secondly, the Hand Men can block all movement on a section of the plane, forcing rather abrupt lateral movements, which can easily deceive the player. Finally, the visibility on the chasms is not exceptional, so it is easy to misjudge their length: it is common to make a jump that is too short or too long. This would be immediately be punished, since there is no possibility to slow down once in the air.

In terms of game design, the title is thus rather formal and sometimes a little too cruel for its own good. Jumping on the pillars is trivial, once you've bounced off the top of one, but getting there is another story. The game sometimes changes the running speed, which fools muscle memory. Some of the collisions are quite strange and having to bump into pillars to find possible tiems is a clunky system. On the other hand, the stereoscopic 3D is rather successful and the game exploits it well during boss fights, where the title turns into a shooter. The character evolves exclusively on a frontal plane and it is a matter of bombarding the snake with missiles, knowing that it is moving in a 3D environment. It oscillates between the background and the space behind the player, so it essential to anticipate its position, in order to maximize the damage done. In this context, stereoscopic 3D is a good addition, because it makes it really easy to determine whether the boss is in front or behind you. Beyond these sequences, the 3D is marginally useful. In the running sections, the size of the sprites is enough to indicate distances and the 3D, although immersive, seems superfluous. 3-D WorldRunner was never successful, but it was more of a technical showcase, intended to test Gebelli's programming skills. In this respect, the game has achieved its purpose.