‘You know what I hate most in the world? Hope, Faith, Love, and Luck.’

Played with BertKnot, through the remastered collection, to which the score applies.

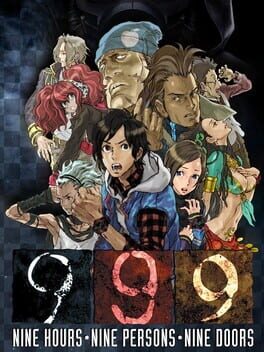

In 2009, Kotaro Uchikoshi presented a new idea, resulting in the Zero Escape series. Some of the themes were already present in his previous works, such as Ever17: The Out of Infinity (2003) or 12Riven: The ΨCliminal of Integral (2008). The concept of an enclosed environment serving as a setting for a mystery was already present, continuing a well-known convention of detective fiction. While these seminal titles were visual novels and offered only limited interaction, Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors interweaves novel sequences with gameplay-driven sections in the form of escape rooms. The most obvious roots of this idea can be found in Myst (1993), which largely popularised the formula of a first-person game – especially browser games –, harkening back to the legacy of the traditional point-n-click games. Initially designed for the DS, Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors is one of the console's legendary titles, both for its unique nature and its clever and intuitive use of the hardware. In 2017, a compilation of all three games in the series was released, allowing players to experience the entire franchise on the latest platforms, with new modern visuals and quality of life options.

The player assumes the role of Junpei, who wakes up in a cabin closed by a strange mechanism, having been kidnapped by a mysterious masked figure. Immediately, the title introduces its escape room mechanics: the player must navigate between several fixed screens and interact with different objects, in order to find a way to open the door of the room. Puzzles punctuate these sequences, often codes to solve or small mathematical problems: they never represent a tremendous challenge, especially as they are often based on the same repeating themes, but they always provide a sense of satisfaction when they are solved. After leaving the cabin Junpei meets eight other characters who have also been captured by Zero. The latter makes contact with the group and explains that they will have to work together to escape; however, the story and the motivations of each character seem to be more complex than they appear. The game involves progressing through the different rooms, while solving the mysteries and murders that occur against the backdrop of these sordid games.

Whilst the remastered version may evoke the Danganronpa series, 999 is surprisingly humble in its direction. The escape rooms do not deviate from their gimmicks and a real emphasis is set on the puzzles, whose difficulty is calibrated to be accessible to the greatest number. It is during the visual novel sequences that the storyline becomes more intense and the plot thickens. In these sections, the player sometimes has to choose an option, such as the next door they want to go through. A playthrough takes the player past three different doors, leading to various endings. Three of them are considered bad outcomes, contrasting with the normal ending and the true one. Regardless of which branchings are selected, a specific door will always lead to the same room and the same puzzles, although new dialogues might also appear, depending on the choices previously made. This strict dichotomy between narrative and gameplay may come as a surprise, especially in the original version, in which the player was forced to redo a new route in its entirety, regardless of whether they had already solved a room in a previous playthrough.

The remaster introduced the Flow, a diagram that summarises the story's junctions and allows the player to skip parts of the game that have already been played. The pacing has thus been quickened and it is now possible to finish the title in half the time it took on the Nintendo DS. This added quality of life is certainly understandable by modern standards regarding visual novels, but it is difficult not to feel as if the game has lost part of its appeal. The transition to newer platforms has removed the DS's distinctive sprites for more traditional and standardised design. The 16:9 resolution makes some of the environments a little too wide and loses the spatial narrowness implied by the smaller screens. As for the Japanese dubbing, it features talented voice actors – Ace is voiced by the prestigious Takaya Hashi, while Snake and Lotus are dubbed by Takahiro Sakurai and Rie Tanaka, respectively – and, while it sheds the magic of the indistinct dialogue noises, it nevertheless suits the game's tone. The bleakest aspect of the remaster is certainly the closing hours of the game. They suffer sorely from not having the dual screens of Nintendo's console; worse still, the final puzzle has been replaced by a painfully hollow enigma, utterly shattering the tension of the finale.

Beyond the notion of conservation, it is tough not to consider the remaster as a downgraded version of the original title. Certainly, the addition of Flow saves time, but its implementation also lacks elegance and clarity to really deserve laurels and make up for the other choices. In 2009, Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors was a unique foray from the Japanese mystery fiction into the West, showcasing a part of the prolific Japanese production. The art direction, halfway between Japanese animation and Western cartoon, accompanied the subversion of the traditional conventions associated with the different characters, and offered a story that was quite unusual compared to the family-friendly releases that most Nintendo DS owners were used to. The gameplay of the puzzles was likewise tuned for touchscreen use and their remastering is hardly convincing: the occasional wheels that need to be turned are implemented in the most cumbersome way possible, relying on a button to start and stop turning them, whereas the DS version simply let the player use their stylus. It is very noticeable that the remaster was designed for home consoles, as even the PC version doesn't take advantage of the mouse cursor. The decision to discard what made the original version so unique – and at the same time, how could it be retained? – sadly puts the title among the plethora of recent visual novels based on macabre games.

Fortunately, the source material is great enough to compensate for these shortcomings. The story unfolds organically and offers a clever mystery, which very alert players will be able to anticipate, carried by a charming and never obnoxious cast: their interactions feel natural, as the characters are more than the trope they initially embody and have the merit of being mostly adults. Admittedly, the gender representation remains within the sexist clichés of Japanese anime, but there is some effort to bring more depth to the various figures. This makes their explanations of the numerous scientific experiments quite apropos and believeworthy – even when it comes to pseudo-sciences –, although one could be dubious when faced with someone knowledgeable about every single trivia regarding the sinking of the Titanic. By and large, the title avoids being too long-winded, except perhaps for the repetitions between the normal and the true endings – albeit diegetically warranted. The game never falls into gratuitous cruelty and shows respect for the individuality of each character, contrasting very favourably with Danganronpa.

It is tough to blame Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors, in its remastered version, for being a disappointment, as it is constrained by more recent systems, for whom the puzzles were not designed. Simultaneously, it is arduous not to consider this version as half-baked and lacking in identity. Some graphical assets have been destroyed by the upscale and the UI has a very unpleasant amateurish quality. In spite of that, 999 remains a title of rare quality, capable of surprising the player unaccustomed to the detective genre. The respect for its cast makes it an enjoyable experience from start to finish and establishes it as a classic for anyone interested in either mysteries or escape rooms. If the absence of the Flow system is not inconvenient, the DS version is still the one to recommend, so as to enjoy the game experience as imagined by Kotaro Uchikoshi.

Played with BertKnot, through the remastered collection, to which the score applies.

In 2009, Kotaro Uchikoshi presented a new idea, resulting in the Zero Escape series. Some of the themes were already present in his previous works, such as Ever17: The Out of Infinity (2003) or 12Riven: The ΨCliminal of Integral (2008). The concept of an enclosed environment serving as a setting for a mystery was already present, continuing a well-known convention of detective fiction. While these seminal titles were visual novels and offered only limited interaction, Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors interweaves novel sequences with gameplay-driven sections in the form of escape rooms. The most obvious roots of this idea can be found in Myst (1993), which largely popularised the formula of a first-person game – especially browser games –, harkening back to the legacy of the traditional point-n-click games. Initially designed for the DS, Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors is one of the console's legendary titles, both for its unique nature and its clever and intuitive use of the hardware. In 2017, a compilation of all three games in the series was released, allowing players to experience the entire franchise on the latest platforms, with new modern visuals and quality of life options.

The player assumes the role of Junpei, who wakes up in a cabin closed by a strange mechanism, having been kidnapped by a mysterious masked figure. Immediately, the title introduces its escape room mechanics: the player must navigate between several fixed screens and interact with different objects, in order to find a way to open the door of the room. Puzzles punctuate these sequences, often codes to solve or small mathematical problems: they never represent a tremendous challenge, especially as they are often based on the same repeating themes, but they always provide a sense of satisfaction when they are solved. After leaving the cabin Junpei meets eight other characters who have also been captured by Zero. The latter makes contact with the group and explains that they will have to work together to escape; however, the story and the motivations of each character seem to be more complex than they appear. The game involves progressing through the different rooms, while solving the mysteries and murders that occur against the backdrop of these sordid games.

Whilst the remastered version may evoke the Danganronpa series, 999 is surprisingly humble in its direction. The escape rooms do not deviate from their gimmicks and a real emphasis is set on the puzzles, whose difficulty is calibrated to be accessible to the greatest number. It is during the visual novel sequences that the storyline becomes more intense and the plot thickens. In these sections, the player sometimes has to choose an option, such as the next door they want to go through. A playthrough takes the player past three different doors, leading to various endings. Three of them are considered bad outcomes, contrasting with the normal ending and the true one. Regardless of which branchings are selected, a specific door will always lead to the same room and the same puzzles, although new dialogues might also appear, depending on the choices previously made. This strict dichotomy between narrative and gameplay may come as a surprise, especially in the original version, in which the player was forced to redo a new route in its entirety, regardless of whether they had already solved a room in a previous playthrough.

The remaster introduced the Flow, a diagram that summarises the story's junctions and allows the player to skip parts of the game that have already been played. The pacing has thus been quickened and it is now possible to finish the title in half the time it took on the Nintendo DS. This added quality of life is certainly understandable by modern standards regarding visual novels, but it is difficult not to feel as if the game has lost part of its appeal. The transition to newer platforms has removed the DS's distinctive sprites for more traditional and standardised design. The 16:9 resolution makes some of the environments a little too wide and loses the spatial narrowness implied by the smaller screens. As for the Japanese dubbing, it features talented voice actors – Ace is voiced by the prestigious Takaya Hashi, while Snake and Lotus are dubbed by Takahiro Sakurai and Rie Tanaka, respectively – and, while it sheds the magic of the indistinct dialogue noises, it nevertheless suits the game's tone. The bleakest aspect of the remaster is certainly the closing hours of the game. They suffer sorely from not having the dual screens of Nintendo's console; worse still, the final puzzle has been replaced by a painfully hollow enigma, utterly shattering the tension of the finale.

Beyond the notion of conservation, it is tough not to consider the remaster as a downgraded version of the original title. Certainly, the addition of Flow saves time, but its implementation also lacks elegance and clarity to really deserve laurels and make up for the other choices. In 2009, Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors was a unique foray from the Japanese mystery fiction into the West, showcasing a part of the prolific Japanese production. The art direction, halfway between Japanese animation and Western cartoon, accompanied the subversion of the traditional conventions associated with the different characters, and offered a story that was quite unusual compared to the family-friendly releases that most Nintendo DS owners were used to. The gameplay of the puzzles was likewise tuned for touchscreen use and their remastering is hardly convincing: the occasional wheels that need to be turned are implemented in the most cumbersome way possible, relying on a button to start and stop turning them, whereas the DS version simply let the player use their stylus. It is very noticeable that the remaster was designed for home consoles, as even the PC version doesn't take advantage of the mouse cursor. The decision to discard what made the original version so unique – and at the same time, how could it be retained? – sadly puts the title among the plethora of recent visual novels based on macabre games.

Fortunately, the source material is great enough to compensate for these shortcomings. The story unfolds organically and offers a clever mystery, which very alert players will be able to anticipate, carried by a charming and never obnoxious cast: their interactions feel natural, as the characters are more than the trope they initially embody and have the merit of being mostly adults. Admittedly, the gender representation remains within the sexist clichés of Japanese anime, but there is some effort to bring more depth to the various figures. This makes their explanations of the numerous scientific experiments quite apropos and believeworthy – even when it comes to pseudo-sciences –, although one could be dubious when faced with someone knowledgeable about every single trivia regarding the sinking of the Titanic. By and large, the title avoids being too long-winded, except perhaps for the repetitions between the normal and the true endings – albeit diegetically warranted. The game never falls into gratuitous cruelty and shows respect for the individuality of each character, contrasting very favourably with Danganronpa.

It is tough to blame Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors, in its remastered version, for being a disappointment, as it is constrained by more recent systems, for whom the puzzles were not designed. Simultaneously, it is arduous not to consider this version as half-baked and lacking in identity. Some graphical assets have been destroyed by the upscale and the UI has a very unpleasant amateurish quality. In spite of that, 999 remains a title of rare quality, capable of surprising the player unaccustomed to the detective genre. The respect for its cast makes it an enjoyable experience from start to finish and establishes it as a classic for anyone interested in either mysteries or escape rooms. If the absence of the Flow system is not inconvenient, the DS version is still the one to recommend, so as to enjoy the game experience as imagined by Kotaro Uchikoshi.

Lucca202

1 year ago