‘Shame on the night, for places I've been and what I've seen.’

– Dio, 'Shame on the Night', 1983.

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (Feb. 21 – Feb. 27, 2023).

Dio was formed under the difficult auspices of the Black Sabbath break-up. The band's aesthetic came from the American counterculture, fuelled by opposition to the Vietnam War and support for hot summers. 1967 saw the explosion of the hippie movement after the Summer of Love. Black Sabbath's albums went in the opposite direction, emphasising a very dark and hopeless aesthetic. The 1970s was a desert without salvation, which the band explored in their albums. Stagflation and the 1973 oil crisis made the middle class feel that they had been crushed by the economic situation: this rather white demographic saw people of colour as an ideal scapegoat, reinforcing the racial tensions of the previous decade. There was also a growing distrust of the political establishment, crystallised by the figure of Nixon and the scandals surrounding his administration.

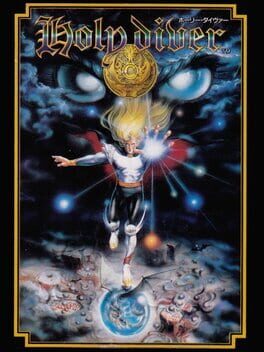

Conflicts over the Live Evil album (1983) led to Dio and Appice leaving Black Sabbath in 1982 to form their own band, Dio. Holy Diver (1983) marked a departure from the themes of Black Sabbath, with a simplified universe. The references to medieval and Christian material are still present, but the album has a much more heroic and fantastical flavour. This thematic streamlining worked very well and Holy Diver became a hard rock staple. When Irem decided to use the album as the basis for an eponymous platformer in 1989, the result was a strange melting pot that mostly just piled references in every direction, from King Crimson to Randy Rhoads.

The player is Randy, who had to flee to a parallel dimension to escape the Black Slayer's assault on the Crimson Kingdom. Now grown up, he embarks on an adventure across six different worlds to destroy this evil. The title is largely inspired by Konami's action platformers, with Castlevania (1986) at the top of the list. Randy attacks by firing fireballs, which have a fairly short range. As in Adventure of Link (1987), he can use magic to help him progress: the Twin Fire doubles the number of projectiles fired and increases the range of attacks, while the Blizzard freezes lava and small enemies. With each level, the player gains a new spell to add to their grimoire. However, unlike Castlevania, where the use of secondary weapons was optional, Holy Diver requires the use of at least the Blizzard and Overdrive to progress through the platforming. This approach makes magic an important resource to conserve, even though it is an indispensable tool for clearing hordes of enemies.

Holy Diver is particularly sadistic in its enemy placement. Many commentators have pointed out the extremely high difficulty of the title, and BrTedford rightly noted that the title feels almost like a puzzle game. Each room requires the player to find an optimal path and play around with enemy spawn locations to get rid of them in an orderly fashion. While Overdrive is a solid defensive option, it is not perfect and requires caution. The game design pushes the player to make deliberate moves and manage their resources intelligently. This wouldn't be a bad concept if the title wasn't weighed down by the stiffness of its movements. Some precise jumps become an ordeal with Randy's airborne inertia; the character sometimes has a strange delay when turning or jumping, which proves critical when enemies are attacking from both sides.

Regrettably, the title never really reaches its full potential. The levels are all very similar, with a succession of long horizontal corridors or vertical shafts in the style of Metroid (1986). The lava mechanic is quickly worn out, and the game only subverts it once for a single secret passage. This lack of creativity is also evident in the bosses, where strategy often comes down to finding a safe spot rather than using spells creatively. Surprisingly, none of them make use of Blizzard. The sprite flickering, already problematic throughout the levels, often becomes unbearable during these boss fights, certainly the worse-designed parts. The Eye Column is morbidly boring despite a seemingly interesting concept, while Embodiment of Evil is so difficult that the developers probably had to add the alcoves on the sides of the arena to allow players to use the Overdrive from there.

The Holy Diver album carried the legacy of rock history and was an aesthetically new proposition from Dio. 'Don't Talk to Strangers' has a certain contemplative quality, while 'Shame on the Night' takes on a playful, teasing quality. The world of Dio's Holy Diver is a reimagining of the Christian epic with rich fantasy overtones. The game of the same name evokes none of its elements. The enemies are all generic and lazily borrowed from Castlevania, Deadly Towers (1986) or Wizards & Warriors (1997), and the environments are generally monochrome and devoid of any flair. Admittedly, this is only an unofficial adaptation, but why invoke Dio's album and the names of so many famous bands if not to make something of them? In the end, Holy Diver is a functional game, driven by an extremely sharp difficulty that it never manages to justify. There are a few ideas here and there, but they are always one-offs that are immediately forgotten. Jeff Wayne's The War of the Worlds (1998) managed to establish a unique atmosphere with its unusual soundtrack for a video game, creating a cohesive product that synthesised very different aesthetics and eras. Holy Diver is nothing like that.

– Dio, 'Shame on the Night', 1983.

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (Feb. 21 – Feb. 27, 2023).

Dio was formed under the difficult auspices of the Black Sabbath break-up. The band's aesthetic came from the American counterculture, fuelled by opposition to the Vietnam War and support for hot summers. 1967 saw the explosion of the hippie movement after the Summer of Love. Black Sabbath's albums went in the opposite direction, emphasising a very dark and hopeless aesthetic. The 1970s was a desert without salvation, which the band explored in their albums. Stagflation and the 1973 oil crisis made the middle class feel that they had been crushed by the economic situation: this rather white demographic saw people of colour as an ideal scapegoat, reinforcing the racial tensions of the previous decade. There was also a growing distrust of the political establishment, crystallised by the figure of Nixon and the scandals surrounding his administration.

Conflicts over the Live Evil album (1983) led to Dio and Appice leaving Black Sabbath in 1982 to form their own band, Dio. Holy Diver (1983) marked a departure from the themes of Black Sabbath, with a simplified universe. The references to medieval and Christian material are still present, but the album has a much more heroic and fantastical flavour. This thematic streamlining worked very well and Holy Diver became a hard rock staple. When Irem decided to use the album as the basis for an eponymous platformer in 1989, the result was a strange melting pot that mostly just piled references in every direction, from King Crimson to Randy Rhoads.

The player is Randy, who had to flee to a parallel dimension to escape the Black Slayer's assault on the Crimson Kingdom. Now grown up, he embarks on an adventure across six different worlds to destroy this evil. The title is largely inspired by Konami's action platformers, with Castlevania (1986) at the top of the list. Randy attacks by firing fireballs, which have a fairly short range. As in Adventure of Link (1987), he can use magic to help him progress: the Twin Fire doubles the number of projectiles fired and increases the range of attacks, while the Blizzard freezes lava and small enemies. With each level, the player gains a new spell to add to their grimoire. However, unlike Castlevania, where the use of secondary weapons was optional, Holy Diver requires the use of at least the Blizzard and Overdrive to progress through the platforming. This approach makes magic an important resource to conserve, even though it is an indispensable tool for clearing hordes of enemies.

Holy Diver is particularly sadistic in its enemy placement. Many commentators have pointed out the extremely high difficulty of the title, and BrTedford rightly noted that the title feels almost like a puzzle game. Each room requires the player to find an optimal path and play around with enemy spawn locations to get rid of them in an orderly fashion. While Overdrive is a solid defensive option, it is not perfect and requires caution. The game design pushes the player to make deliberate moves and manage their resources intelligently. This wouldn't be a bad concept if the title wasn't weighed down by the stiffness of its movements. Some precise jumps become an ordeal with Randy's airborne inertia; the character sometimes has a strange delay when turning or jumping, which proves critical when enemies are attacking from both sides.

Regrettably, the title never really reaches its full potential. The levels are all very similar, with a succession of long horizontal corridors or vertical shafts in the style of Metroid (1986). The lava mechanic is quickly worn out, and the game only subverts it once for a single secret passage. This lack of creativity is also evident in the bosses, where strategy often comes down to finding a safe spot rather than using spells creatively. Surprisingly, none of them make use of Blizzard. The sprite flickering, already problematic throughout the levels, often becomes unbearable during these boss fights, certainly the worse-designed parts. The Eye Column is morbidly boring despite a seemingly interesting concept, while Embodiment of Evil is so difficult that the developers probably had to add the alcoves on the sides of the arena to allow players to use the Overdrive from there.

The Holy Diver album carried the legacy of rock history and was an aesthetically new proposition from Dio. 'Don't Talk to Strangers' has a certain contemplative quality, while 'Shame on the Night' takes on a playful, teasing quality. The world of Dio's Holy Diver is a reimagining of the Christian epic with rich fantasy overtones. The game of the same name evokes none of its elements. The enemies are all generic and lazily borrowed from Castlevania, Deadly Towers (1986) or Wizards & Warriors (1997), and the environments are generally monochrome and devoid of any flair. Admittedly, this is only an unofficial adaptation, but why invoke Dio's album and the names of so many famous bands if not to make something of them? In the end, Holy Diver is a functional game, driven by an extremely sharp difficulty that it never manages to justify. There are a few ideas here and there, but they are always one-offs that are immediately forgotten. Jeff Wayne's The War of the Worlds (1998) managed to establish a unique atmosphere with its unusual soundtrack for a video game, creating a cohesive product that synthesised very different aesthetics and eras. Holy Diver is nothing like that.