You're a good person. I know you're a good person! A good person wouldn't do something like that...

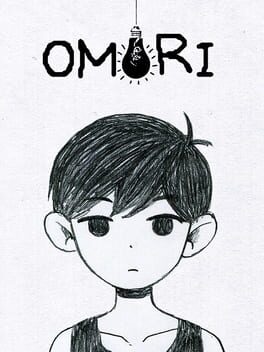

Omori is a game about anxiety, guilt, and moving on from the past to face the real world, and I highly recommend it. Even if it's not the first of its kind to explore the subject matter, it is one of the most interesting executions I've seen of the genre. Charming art, middling but acceptable gameplay, and a pervasive sense of unease and horror set the tone for this very traditional turn-based strategy, with writing and worldbuilding that all work for a payoff that sticks with you.

The rest of this review is going to be spoilers, since it's hard to talk about the game outside of trite cliches otherwise. If you like psychological horror, play it.

---

Omori gets horror. It understands that horror is supposed to be used in service of a central plot, that the creepy-crawlies are supposed to actually represent something, and that the monster in the dark is almost always scarier when you don't fully understand what it is.

We follow Omori, a child who lives in what is very clearly a fantasy world of his own creation populated by friends from his childhood, exploring Headspace and going on adventures to eventually save Basil, his best friend. As the game progresses, elements from his past slowly start to inject themselves into the world at large in ways that fundamentally go against the central light-hearted and shallow tone of the world, often in ways that go completely unacknowledged by Omori's friends. Slowly, we learn the truth of Omori's past and exactly what Sunny is repressing.

Little details of the world are deliberate in how they lead us to the conclusion that something is wrong and that this world is a fantasy, from the very early reveal that the world is called Headspace to how Mari, Omori's sister, is constantly appearing in random locations in the world on her picnic blanket, to how the world does not acknowledge Omori's fears, to how the eventual diversions from the quest to save Basil get more and more disconnected from reality as cohesive worldbuilding starts to fall apart as they reach the limits of imagination.

In a lot of ways, the happy and lighthearted tone of the game itself serves to accent the horror; elements of horror go unacknowledged in increasingly blatant ways, making the juxtaposition of the something that haunts Omori poison the sanctity of the world he has created for himself. Suddenly, every happy moment becomes tense as you pretend that you aren't breaking apart at the seams in both your dream world and reality, and it turns a game that is only about 15% horror into something deeply tense. It's an extremely accurate way to simulate anxiety and forcing yourself to interact with the world despite it. This is, in my mind, the strongest part of the game, and this tension is reason alone to play it.

The central gimmick of the combat system is a rock-paper-scissors element of happiness, anger, and sadness, with each beating the next in turn. As both allies and enemies experience greater and greater peaks of emotion, they get stronger and stronger while also growing more vulnerable, with proper play involving the control of not just your emotions, but the emotions of enemies to properly optimize your skills. It helps to serve the underlying theme of how repression fundamentally cannot help solve our problems, and that our emotions and connections form our strongest assets, and while I love the concept, the execution of combat in the moment is occasionally tedious and lasts much longer than it feels like it should.

As time goes on, we slowly learn exactly what we are repressing, and the game takes on its second major theme of forgiveness and how we deserve to move on from guilt. It's revealed that Sunny, Omori's real life counterpart, killed Mari in what is implied to be an accidental shove down a flight of stairs and, with Basil's assistance, staged her body to fake her suicide. The thing that has been haunting Sunny this entire time is the twisted form of Mari's hanging corpse, and the game turns (at least in one route) to one where Sunny is forced to both confront the truth of what he did and learn to forgive himself and move past his guilt. This, also, is executed extremely well, and depending on what you do with this information, the game ends with you either succeeding or failing to forgive yourself for your crimes.

I've struggled with a version of this kind of guilt for most of my life. While the true ending finishes with Sunny defeating their inner demons and hoping that his friends will come to forgive him, the neutral ending finishes with Sunny haunted by the ghost of his past, following him into the future forever. The game is very earnest about believing that forgiveness is always possible, even if it leaves a scar, even if it means that some part of you (say, your right eye) will always be left behind, even if it means that things won't ever truly be the same.

It is this last part that, in my mind, is the weakest part of the game; I'm sure that many will come away with the message that Sunny can fully move on, as though his crimes will not live with him forever, as though some mistakes that haunt you can just be accepted. In many ways, the game is explicit about how we all can be forgiven, often without consequence; even if we did a bad thing, the game says, we aren't necessarily bad people.

Sometimes, I wished I believed that.

Omori is a game about anxiety, guilt, and moving on from the past to face the real world, and I highly recommend it. Even if it's not the first of its kind to explore the subject matter, it is one of the most interesting executions I've seen of the genre. Charming art, middling but acceptable gameplay, and a pervasive sense of unease and horror set the tone for this very traditional turn-based strategy, with writing and worldbuilding that all work for a payoff that sticks with you.

The rest of this review is going to be spoilers, since it's hard to talk about the game outside of trite cliches otherwise. If you like psychological horror, play it.

---

Omori gets horror. It understands that horror is supposed to be used in service of a central plot, that the creepy-crawlies are supposed to actually represent something, and that the monster in the dark is almost always scarier when you don't fully understand what it is.

We follow Omori, a child who lives in what is very clearly a fantasy world of his own creation populated by friends from his childhood, exploring Headspace and going on adventures to eventually save Basil, his best friend. As the game progresses, elements from his past slowly start to inject themselves into the world at large in ways that fundamentally go against the central light-hearted and shallow tone of the world, often in ways that go completely unacknowledged by Omori's friends. Slowly, we learn the truth of Omori's past and exactly what Sunny is repressing.

Little details of the world are deliberate in how they lead us to the conclusion that something is wrong and that this world is a fantasy, from the very early reveal that the world is called Headspace to how Mari, Omori's sister, is constantly appearing in random locations in the world on her picnic blanket, to how the world does not acknowledge Omori's fears, to how the eventual diversions from the quest to save Basil get more and more disconnected from reality as cohesive worldbuilding starts to fall apart as they reach the limits of imagination.

In a lot of ways, the happy and lighthearted tone of the game itself serves to accent the horror; elements of horror go unacknowledged in increasingly blatant ways, making the juxtaposition of the something that haunts Omori poison the sanctity of the world he has created for himself. Suddenly, every happy moment becomes tense as you pretend that you aren't breaking apart at the seams in both your dream world and reality, and it turns a game that is only about 15% horror into something deeply tense. It's an extremely accurate way to simulate anxiety and forcing yourself to interact with the world despite it. This is, in my mind, the strongest part of the game, and this tension is reason alone to play it.

The central gimmick of the combat system is a rock-paper-scissors element of happiness, anger, and sadness, with each beating the next in turn. As both allies and enemies experience greater and greater peaks of emotion, they get stronger and stronger while also growing more vulnerable, with proper play involving the control of not just your emotions, but the emotions of enemies to properly optimize your skills. It helps to serve the underlying theme of how repression fundamentally cannot help solve our problems, and that our emotions and connections form our strongest assets, and while I love the concept, the execution of combat in the moment is occasionally tedious and lasts much longer than it feels like it should.

As time goes on, we slowly learn exactly what we are repressing, and the game takes on its second major theme of forgiveness and how we deserve to move on from guilt. It's revealed that Sunny, Omori's real life counterpart, killed Mari in what is implied to be an accidental shove down a flight of stairs and, with Basil's assistance, staged her body to fake her suicide. The thing that has been haunting Sunny this entire time is the twisted form of Mari's hanging corpse, and the game turns (at least in one route) to one where Sunny is forced to both confront the truth of what he did and learn to forgive himself and move past his guilt. This, also, is executed extremely well, and depending on what you do with this information, the game ends with you either succeeding or failing to forgive yourself for your crimes.

I've struggled with a version of this kind of guilt for most of my life. While the true ending finishes with Sunny defeating their inner demons and hoping that his friends will come to forgive him, the neutral ending finishes with Sunny haunted by the ghost of his past, following him into the future forever. The game is very earnest about believing that forgiveness is always possible, even if it leaves a scar, even if it means that some part of you (say, your right eye) will always be left behind, even if it means that things won't ever truly be the same.

It is this last part that, in my mind, is the weakest part of the game; I'm sure that many will come away with the message that Sunny can fully move on, as though his crimes will not live with him forever, as though some mistakes that haunt you can just be accepted. In many ways, the game is explicit about how we all can be forgiven, often without consequence; even if we did a bad thing, the game says, we aren't necessarily bad people.

Sometimes, I wished I believed that.