"When you're pushed, killing's as easy as breathing."

Video games are violent.

Shocker, I know. Stunned silence across the board, I'm sure. The conversation around violence in games is one that is as old as the medium itself, and is maybe the most misguided and exhausting of the conversations around the medium, in the mainstream at least. Largely, I think this is because the counter-response to the, indeed, worthy-of-critique ubiquity of games were you hurt and kill others, is so routinely embarrassing.

If you google "non-violent video games", one of the first games that crops up is Cities: Skylines. While it is true that you do not personally murder anyone with a sword in Cities: Skylines, and setting aside the fact that you can use disasters to commit absolute genocide of your largely invisible population, to describe Cities: Skylines as a non-violent game is mind-bogglingly ridiculous to me. The ideology that drives this game - indeed, one that drives the entire genre - is that of growth - growth upon growth, nothing but growth in this blasted land, the incarnation of Reaganomics, the management of the human mind through the construction of the space around them to ensure efficiency.

Sure, Cities: Skylines is slightly less toxic than it's overbearing predecessor SimCity, the breakout title from Will Wright, who's game development portfolio consists almost entirely of adaptations of neo-conservative texts he consumed completely uncritically. It has a huge emphasis on public transport, and the gameplay loop of that title is defined by your attempt to stem the tide of traffic clogging the arteries of your city with the kind of Smart, Walkable, Mixed-Use Urbanism that is Illegal To Build In Most American Cities...as long as it still fits within the image of the American megalopolis super-city. Everything about Cities: Skylines pushes you to grow, small cosy towns at one with nature are not considered a valid end goal but an implicit failure to follow the path of perpetual growth, of endless explosive population and income increase, to make a city of towering skyscrapers, booming industry, bustling streets, to the point that the game will constrain your creative powers until you meet certain thresholds of population and size.

One need only look at London, New York, Los Angeles, Dublin, hell, even my own home city of Belfast, tiny as it is in comparison to these others, to see the consequences of this ideology. Their impact on the world ecologically, their impact on how we live our lives, their impact on our mental state...this is all violence, real violence, but violence that is abstracted, violence where you can't see the knife and the throat it cuts into, until you really look, until you see all those curved benches around town that hurt to lie on, that no longer have backrests or are dotted with little "armrests" for what they really are.

By any reasonable metric that understands how the world works and how systems and laws can cause harm to others, Cities: Skylines is a violent video game. Even a player that is conscious of the environment, that takes the time to produce robust public transport solutions, you're almost certainly going to commit more violence to the little abstract people of Spunkburg or whatever than Solid Snake could manage over the course of his mission to Shadow Moses. But it doesn't feel that way, because the violence is abstracted, hidden behind spreadsheets and charts and corporate focus-tested interface design, all rounded edges and pastel colors. The violence is abstract, over there.

Now, I'm far from the first person to say this, and there is plenty of conversation about violent video games that takes an actual understanding of what material violence actually is into account. But most of that conversation is relegated to either actual academic spaces or occasionally, in alternative academic works on YouTube or, indeed, Backloggd. Rarely does it percolate into the mainstream discourse enough to change the conception of what a violent video game actually is. The kind of mainstream critique of violent video games - one that can be seen most strongly in the Wholesome Games movement - does not seem to me an actual objection to Violence, but a discomfort with it's presentation, with the fact that the violence of tearing open an Imp's head in Doom Eternal is impossible to ignore as anything other than the violent act that it is. It is not an actual concern about the depiction or normalization of violence in video games, it is principally, an objection to the viscera of it's presentation. It is, if you will pardon my French, a bourgeois indulgence.

I don't think it's impossible to make truly non-violent video games, nor do I think that the ubiquity of games where the primary/sole modes of interaction it facilitates is killing is unworthy of critique. But I do think that the nature of what violence actually is makes that far more difficult than one might initially think.

Let me explain by talking about something that I think Backloggd would do well to consider more often: Board Games. If one was so inclined, one could categorize most any board game into one of two camps: abstract games, and thematic games. A thematic board game is one that would use an aesthetic, narrative, or other kind of theming in order to place the mechanics of the game into a context in order to facilitate the intentions of the game. For example, Monopoly is a game where each player plays the role of a real-estate/business mogul who is travelling around London/New York/The Fortnite Island buying up properties in order to eventually win the game by being the player with the most money at the end. As a game where the explicit goal is to bankrupt every other player, Monopoly is plainly a Violent Board Game, even if at no point does your little top hat take out a gun and shoot the thimble in the head. But what about Abstract games? Chess is probably the most famous abstract game in the world, it's mechanics and rules are offered no real justification or contextualization by a theme - castles, in real life, contrary to Chess' bizarre worldview, can actually move diagonally. And yet, despite this, the violence of the real world creeps into Chess. It's pieces are named according to the hierarchy of the feudal system, with higher pieces being ever more powerful and capable, up to the King, who is functionally invincible in a way the other pieces aren't.

What about Go? This Chinese abstract game that is at least 2500 years old, predating most of the concepts that have been mentioned in this review, doesn't even have named spaces or concepts - players simply take turns placing colored pieces and whoever has the most points at the end wins. But even though Go doesn't have anything resembling a traditional theme, it remains a game of violence - most obviously through the way an opponents pieces can be captured, but also through how scores are tallied, through how big the territory you control is. Even though there are no soldiers, even though there is none of the formal mechanisms of violence, conversations about Go refer to it's movements and situations as battles in a war because the mechanics are derived from violent social constructions about the capture and ownership of territory and individuals.

The dichotomy between theme and abstract is not as present in video games, but there does remain a sliding scale between games that attempt some form of verisimilitude in it's visuals and play, and those that preference kinesthetic interaction far more than caring to contextualize that. Which brings me, at last, to Libble Rabble.

Libble Rabble is the game that I thought about the most while playing Quantum Bummer Blues. This arcade classic from the designer of Pac-Man is far from the traditional image of "violent video game" that that phrase conjures. It is a (mostly) abstract game where the player controls two cursors at once, drawling lines around pegs in the game space to capture space inside them. There is no real context for who the player is or why they are doing this, and yet, much like Chess or Go, the violence of our society is inherent in these mechanics. Encircling land on the map changes it's hue, marking your territory like an explorer planting a flag of plain colors, and if you happen to capture objects or creatures in that territory, they vanish, and in their place, offer points. The encirclement and capture of living creatures is core to the loop of Libble Rabble.

I don't say this to condemn Libble Rabble - I have no actual ethical concerns about it whatsoever - nor to make a statement along the lines of "Pac-Man is actually a guy taking a load of drugs at a rave". Instead, I hope all of this has convincingly demonstrated that violence, as a concept, exists on so many levels beyond the act of hurting virtual dolls (incidentally, please read Vehmently's incredible piece on that particular aesthetic subject ) and that "non-violent games" are instead merely games that successfully abstract out their violence so that we can be comforted by the illusion of it's non-presence, and that the fetishization of that illusion leads us to uncomfortable places.

Violence is not inescapable in play, but games are violent, and they are violent because we are violent, because they are made, produced, and played by a culture where violence is ubiquitous. Not because human beings are a kind of hobbesian construct of pure violence and that Link slashing a bokoblin in some way taps into a fundamental human instinct towards harming others, but because we live in a violent and flammable world that snaps and twists and folds our limbs into origami shapes that fold our mind into thoughts and places where violence is normal. We probably aren't going to juggle-combo an opponent in the King of Iron First Tournament in our everyday lives, but violence is all around us, it is inherent to the structures and systems that entomb us, it's only hidden from view, abstracted and blurred by those same systems, and it is only when the abstraction is removed and the image is in focus do we acknowledge it for what it is.

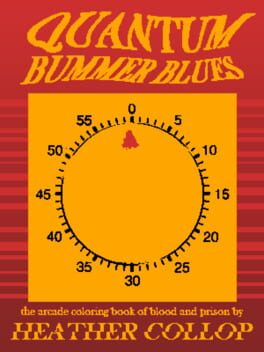

It is this that is so remarkable about Quantum Bummer Blues. In play, it bears remarkable similarity to abstract games, and Libble Rabble in particular, feels to me like a clear ancestor of this game's design. But unlike all these other games, QBB marks it's body deep with the violence of our world, never allowing anything you do to be comfortably abstracted. Any potential implication of the premise of it's play is fully incorporated - what could be a simple contextless line is a trail of blood leaning away from a murdered corpse, and each action is contextualized by the game's compelling stream-of-consciousness writing. Self-harm is a mechanic in this game, a delicate balance that was the only way I got as far as I did, and the game faces this head-on. And the abstract maze that you bleed through is a prison tucked far out of earth's sight, where human minds and bodies are bent and broken and twisted into shapes that are comforting to our bourgeois bounds of acceptability and comfort. More than a game that deconstructs assumptions of video game mechanics, more than one that exposes a dark truth about the world narratively, QBB, by violently jamming traditionally abstract arcade-style mechanics into an aesthetic and narrative framework that absolutely refuses to fade into the background and let itself be blurred out, articulates with astonishing clarity just how violent our society and the things it creates is.

In a space that so often dodges the full implications of it's mechanics, where the more serious the themes, the more abstractions are removed, Quantum Bummer Blues is a blast of summer wind, a game that is brutally, angrily honest, about itself, about games, and how these things fit into a burning world. An act not of condemnation, but excoriation.

This is the world. How do you stand it?

It's as easy as breathing.

Video games are violent.

Shocker, I know. Stunned silence across the board, I'm sure. The conversation around violence in games is one that is as old as the medium itself, and is maybe the most misguided and exhausting of the conversations around the medium, in the mainstream at least. Largely, I think this is because the counter-response to the, indeed, worthy-of-critique ubiquity of games were you hurt and kill others, is so routinely embarrassing.

If you google "non-violent video games", one of the first games that crops up is Cities: Skylines. While it is true that you do not personally murder anyone with a sword in Cities: Skylines, and setting aside the fact that you can use disasters to commit absolute genocide of your largely invisible population, to describe Cities: Skylines as a non-violent game is mind-bogglingly ridiculous to me. The ideology that drives this game - indeed, one that drives the entire genre - is that of growth - growth upon growth, nothing but growth in this blasted land, the incarnation of Reaganomics, the management of the human mind through the construction of the space around them to ensure efficiency.

Sure, Cities: Skylines is slightly less toxic than it's overbearing predecessor SimCity, the breakout title from Will Wright, who's game development portfolio consists almost entirely of adaptations of neo-conservative texts he consumed completely uncritically. It has a huge emphasis on public transport, and the gameplay loop of that title is defined by your attempt to stem the tide of traffic clogging the arteries of your city with the kind of Smart, Walkable, Mixed-Use Urbanism that is Illegal To Build In Most American Cities...as long as it still fits within the image of the American megalopolis super-city. Everything about Cities: Skylines pushes you to grow, small cosy towns at one with nature are not considered a valid end goal but an implicit failure to follow the path of perpetual growth, of endless explosive population and income increase, to make a city of towering skyscrapers, booming industry, bustling streets, to the point that the game will constrain your creative powers until you meet certain thresholds of population and size.

One need only look at London, New York, Los Angeles, Dublin, hell, even my own home city of Belfast, tiny as it is in comparison to these others, to see the consequences of this ideology. Their impact on the world ecologically, their impact on how we live our lives, their impact on our mental state...this is all violence, real violence, but violence that is abstracted, violence where you can't see the knife and the throat it cuts into, until you really look, until you see all those curved benches around town that hurt to lie on, that no longer have backrests or are dotted with little "armrests" for what they really are.

By any reasonable metric that understands how the world works and how systems and laws can cause harm to others, Cities: Skylines is a violent video game. Even a player that is conscious of the environment, that takes the time to produce robust public transport solutions, you're almost certainly going to commit more violence to the little abstract people of Spunkburg or whatever than Solid Snake could manage over the course of his mission to Shadow Moses. But it doesn't feel that way, because the violence is abstracted, hidden behind spreadsheets and charts and corporate focus-tested interface design, all rounded edges and pastel colors. The violence is abstract, over there.

Now, I'm far from the first person to say this, and there is plenty of conversation about violent video games that takes an actual understanding of what material violence actually is into account. But most of that conversation is relegated to either actual academic spaces or occasionally, in alternative academic works on YouTube or, indeed, Backloggd. Rarely does it percolate into the mainstream discourse enough to change the conception of what a violent video game actually is. The kind of mainstream critique of violent video games - one that can be seen most strongly in the Wholesome Games movement - does not seem to me an actual objection to Violence, but a discomfort with it's presentation, with the fact that the violence of tearing open an Imp's head in Doom Eternal is impossible to ignore as anything other than the violent act that it is. It is not an actual concern about the depiction or normalization of violence in video games, it is principally, an objection to the viscera of it's presentation. It is, if you will pardon my French, a bourgeois indulgence.

I don't think it's impossible to make truly non-violent video games, nor do I think that the ubiquity of games where the primary/sole modes of interaction it facilitates is killing is unworthy of critique. But I do think that the nature of what violence actually is makes that far more difficult than one might initially think.

Let me explain by talking about something that I think Backloggd would do well to consider more often: Board Games. If one was so inclined, one could categorize most any board game into one of two camps: abstract games, and thematic games. A thematic board game is one that would use an aesthetic, narrative, or other kind of theming in order to place the mechanics of the game into a context in order to facilitate the intentions of the game. For example, Monopoly is a game where each player plays the role of a real-estate/business mogul who is travelling around London/New York/The Fortnite Island buying up properties in order to eventually win the game by being the player with the most money at the end. As a game where the explicit goal is to bankrupt every other player, Monopoly is plainly a Violent Board Game, even if at no point does your little top hat take out a gun and shoot the thimble in the head. But what about Abstract games? Chess is probably the most famous abstract game in the world, it's mechanics and rules are offered no real justification or contextualization by a theme - castles, in real life, contrary to Chess' bizarre worldview, can actually move diagonally. And yet, despite this, the violence of the real world creeps into Chess. It's pieces are named according to the hierarchy of the feudal system, with higher pieces being ever more powerful and capable, up to the King, who is functionally invincible in a way the other pieces aren't.

What about Go? This Chinese abstract game that is at least 2500 years old, predating most of the concepts that have been mentioned in this review, doesn't even have named spaces or concepts - players simply take turns placing colored pieces and whoever has the most points at the end wins. But even though Go doesn't have anything resembling a traditional theme, it remains a game of violence - most obviously through the way an opponents pieces can be captured, but also through how scores are tallied, through how big the territory you control is. Even though there are no soldiers, even though there is none of the formal mechanisms of violence, conversations about Go refer to it's movements and situations as battles in a war because the mechanics are derived from violent social constructions about the capture and ownership of territory and individuals.

The dichotomy between theme and abstract is not as present in video games, but there does remain a sliding scale between games that attempt some form of verisimilitude in it's visuals and play, and those that preference kinesthetic interaction far more than caring to contextualize that. Which brings me, at last, to Libble Rabble.

Libble Rabble is the game that I thought about the most while playing Quantum Bummer Blues. This arcade classic from the designer of Pac-Man is far from the traditional image of "violent video game" that that phrase conjures. It is a (mostly) abstract game where the player controls two cursors at once, drawling lines around pegs in the game space to capture space inside them. There is no real context for who the player is or why they are doing this, and yet, much like Chess or Go, the violence of our society is inherent in these mechanics. Encircling land on the map changes it's hue, marking your territory like an explorer planting a flag of plain colors, and if you happen to capture objects or creatures in that territory, they vanish, and in their place, offer points. The encirclement and capture of living creatures is core to the loop of Libble Rabble.

I don't say this to condemn Libble Rabble - I have no actual ethical concerns about it whatsoever - nor to make a statement along the lines of "Pac-Man is actually a guy taking a load of drugs at a rave". Instead, I hope all of this has convincingly demonstrated that violence, as a concept, exists on so many levels beyond the act of hurting virtual dolls (incidentally, please read Vehmently's incredible piece on that particular aesthetic subject ) and that "non-violent games" are instead merely games that successfully abstract out their violence so that we can be comforted by the illusion of it's non-presence, and that the fetishization of that illusion leads us to uncomfortable places.

Violence is not inescapable in play, but games are violent, and they are violent because we are violent, because they are made, produced, and played by a culture where violence is ubiquitous. Not because human beings are a kind of hobbesian construct of pure violence and that Link slashing a bokoblin in some way taps into a fundamental human instinct towards harming others, but because we live in a violent and flammable world that snaps and twists and folds our limbs into origami shapes that fold our mind into thoughts and places where violence is normal. We probably aren't going to juggle-combo an opponent in the King of Iron First Tournament in our everyday lives, but violence is all around us, it is inherent to the structures and systems that entomb us, it's only hidden from view, abstracted and blurred by those same systems, and it is only when the abstraction is removed and the image is in focus do we acknowledge it for what it is.

It is this that is so remarkable about Quantum Bummer Blues. In play, it bears remarkable similarity to abstract games, and Libble Rabble in particular, feels to me like a clear ancestor of this game's design. But unlike all these other games, QBB marks it's body deep with the violence of our world, never allowing anything you do to be comfortably abstracted. Any potential implication of the premise of it's play is fully incorporated - what could be a simple contextless line is a trail of blood leaning away from a murdered corpse, and each action is contextualized by the game's compelling stream-of-consciousness writing. Self-harm is a mechanic in this game, a delicate balance that was the only way I got as far as I did, and the game faces this head-on. And the abstract maze that you bleed through is a prison tucked far out of earth's sight, where human minds and bodies are bent and broken and twisted into shapes that are comforting to our bourgeois bounds of acceptability and comfort. More than a game that deconstructs assumptions of video game mechanics, more than one that exposes a dark truth about the world narratively, QBB, by violently jamming traditionally abstract arcade-style mechanics into an aesthetic and narrative framework that absolutely refuses to fade into the background and let itself be blurred out, articulates with astonishing clarity just how violent our society and the things it creates is.

In a space that so often dodges the full implications of it's mechanics, where the more serious the themes, the more abstractions are removed, Quantum Bummer Blues is a blast of summer wind, a game that is brutally, angrily honest, about itself, about games, and how these things fit into a burning world. An act not of condemnation, but excoriation.

This is the world. How do you stand it?

It's as easy as breathing.

MalditoMur

1 year ago