Games began as a wholly altruistic medium. Early games are characterized by their hobbling together of primitive technologies with the singular goal to entertain. Playing any given arcade game or Atari 2600 game, all the way to systems like the N64 - arguably even persisting until the 2000s and 2010s - you can surmise very little about a game's author from the content of the game. But in the 2000s, something changed. With the advent of the home computer and the move from enterprise SDKs to downloadable game engines, games could be made by singular people, and could more accurately confront singular interests as literature had over a hundred ago as typewriters began industrial production, and as music had in the 1980s with the cassette revolution.

Even typing this flowery and faux-academic intro out, I feel a bit dirty. He Fucked the Girl Out of Me is real, a true recounting of events. Analyzing it as a piece of fiction is a horrible practice. This game, and media like it that confronts very real and horrible things experienced by real people who just happen to use a certain medium to express those feelings (see: Skeleton Tree, A Crow Looked At Me) live in an odd limbo of perception. I both feel like an interloper observing them - and am filled with the weirdest feeling seeing this game on a rating aggregation site with a 3.5 avergae - but also acknowledge that a game published by an author with other titles was definitely published in a way that is conducive to it being perceived by some kind of public. With that being said, Taylor McCue - the creator of this game - has shown positive reactions to reactions to the game so I have to assume that something like this would be an expected or even appreciated result of airing a subject like this out through a game.

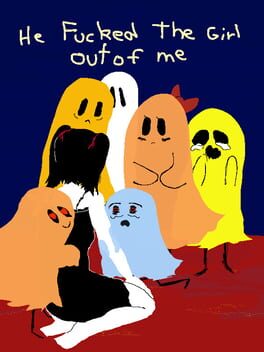

He Fucked the Girl Out of Me, from start to end, is an utterly paralyzing experience. As you walk throughout these simulacra of real places and people, you can feeling the horror and tension in everything. There are no rises or falls, no closure, you merely dredge around these environments and read the dialogue in extremely tight 10-word clusters. Taylor, for the majority of the game, depicts herself as a ghost with a bow - the sole gender connotation for this apperance - in a world of humans. It feels like you're not even living these experiences so much as recounting something that has happened years ago. Even at its most visceral moments this wall is there, yet it never effects the emotions here in any way.

One thing I particularly took notice of going through this game was the (and, spoilers if you want to see it for yourself) singular sound in the entire game. As I started the game, walked through the prologue area and began the story, I just sort of accepted there was no sound. But, when I heard the ding of the phone around the midpoint of that game, that one moment had such a pull to it it feels like the center of the game to me. From then on the silence is a tool the game uses, constantly building pressure from the contrast from this one singular ding.

This might be the most in-depth game I've seen about a singular topic and its effects on its cast, and it is devastating and beautifully rendered the whole way through. I wouldn't dare try to relate myself to this - that would be monstrous - but some of the moments in this game express such a raw pathos I've hardly seen in a game to date.

All in all, I'm just glad she could get it out there.

Even typing this flowery and faux-academic intro out, I feel a bit dirty. He Fucked the Girl Out of Me is real, a true recounting of events. Analyzing it as a piece of fiction is a horrible practice. This game, and media like it that confronts very real and horrible things experienced by real people who just happen to use a certain medium to express those feelings (see: Skeleton Tree, A Crow Looked At Me) live in an odd limbo of perception. I both feel like an interloper observing them - and am filled with the weirdest feeling seeing this game on a rating aggregation site with a 3.5 avergae - but also acknowledge that a game published by an author with other titles was definitely published in a way that is conducive to it being perceived by some kind of public. With that being said, Taylor McCue - the creator of this game - has shown positive reactions to reactions to the game so I have to assume that something like this would be an expected or even appreciated result of airing a subject like this out through a game.

He Fucked the Girl Out of Me, from start to end, is an utterly paralyzing experience. As you walk throughout these simulacra of real places and people, you can feeling the horror and tension in everything. There are no rises or falls, no closure, you merely dredge around these environments and read the dialogue in extremely tight 10-word clusters. Taylor, for the majority of the game, depicts herself as a ghost with a bow - the sole gender connotation for this apperance - in a world of humans. It feels like you're not even living these experiences so much as recounting something that has happened years ago. Even at its most visceral moments this wall is there, yet it never effects the emotions here in any way.

One thing I particularly took notice of going through this game was the (and, spoilers if you want to see it for yourself) singular sound in the entire game. As I started the game, walked through the prologue area and began the story, I just sort of accepted there was no sound. But, when I heard the ding of the phone around the midpoint of that game, that one moment had such a pull to it it feels like the center of the game to me. From then on the silence is a tool the game uses, constantly building pressure from the contrast from this one singular ding.

This might be the most in-depth game I've seen about a singular topic and its effects on its cast, and it is devastating and beautifully rendered the whole way through. I wouldn't dare try to relate myself to this - that would be monstrous - but some of the moments in this game express such a raw pathos I've hardly seen in a game to date.

All in all, I'm just glad she could get it out there.