I'm constantly fascinated by the transition from 2D to 3D. How designers approached this with, literally, an entirely new dimension to consider. The sacrifices they made in doing that. The contrast between A Link to the Past and Ocarina of Time is held up as one of the clearest examples of a team iterating on ideas they introduced in 2D and attempting to flesh them out in 3D, but Metal Gear Solid had its own 2D predecessor that was possibly even more influential to its design. It's just not a game that nearly so many people have played. A lot of Metal Gear Solid and Hideo Kojima's specific eccentricities are a direct result of where they came from. I think if you really want to understand the series, it's quite helpful to have played the originals.

I don't want to make Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake sound like an early prototype, or a demo recording of what would go on to become a classic song. It's an elaborate technical achievement in its own right. While other teams were struggling to draw multiple moving sprites on the fairly rudimentary MSX2 hardware, Kojima's team were creating a dense military base with distinct locations and patrolling enemies actively swarming off-screen. This was still 1990, and if Konami wanted a complicated action game, they'd ask their arcade or Famicom teams. The MSX was more associated with visual novel-style adventure games and conversions of early 80s arcade hits. They were underdogs, attempting the impossible. Metal Gear 2 on the MSX2 is like if they'd made Super Metroid on the Commodore 64 (and back with the schedules and budget constraints of the time, not some endless homebrew project).

I think I ought to talk about Metal Gear 1 a little. That was the result of a lot of compromises and inexperience. Hideo Kojima went into the games industry, excited to find a job that would allow him to express his own ideas and thoughts about the world around him. He was hired by Konami and dumped into the undesirable role of "planner". After some success working on Penguin Adventure, Kojima was tasked with designing a war game for the MSX. Kojima hated war, and it was a challenge to do intense action on the hardware. He decided to subvert the task he'd been given. Inspired by The Great Escape, he came up with a game where you try to avoid conflict and prevent the war from starting. Metal Gear was rushed and crude, coming from an inexperienced team. It controlled like an old Falcom RPG, and the stealth mechanics didn't go much further than having enemies who would fight you if you stood in front of them. There were some really great ideas in it, though. The cardboard boxes and remote-control missiles immediately became hallmarks of the series, though the sequels would make much better use of them.

Kojima went on to create Snatcher, which better allowed him to indulge in his passions of worldbuilding, science fiction, and tales of corporate deceit (a theme that has bitterly mirrored his own career). It also brought him closer to the home computer adventure games he was playing himself, like Yuji Horii's Portopia Serial Murder Case. He was able to explore human drama and complex, multi-layered conspiracy. He put more of himself into it, and each game he directed from that point on would carry a much stronger sense of its creator's voice. It was public demand that pushed him to revisit the Metal Gear concept, and it greatly benefitted from his newfound confidence and insight.

Much of Metal Gear 2's tone and logic is straight out of those 80s adventure games, only with a unique political bent. The age of nuclear deterrence has ended, but Zanzibar Land, a rogue state in Central Asia has been attacking international disposal facilities and amassing the unused warheads. Global oil shortages have caused an energy crisis, and the Czech biologist, Dr Kio Marv has developed a microbe capable of synthesizing petroleum to solve the problem. Dr Marv is kidnapped by Zanzibar Land soldiers, hoping to become the dominant nation in this era of peace. FOX-HOUND sends their top agent, Solid Snake, to recover the scientist and prevent the terrorists from launching a strike.

Metal Gear 2 is equal parts pet-project sincere and blurping moonman whimsy. It can often feel like someone bulked up their Warhammer army with GI Joes. You trick a guard into thinking it's nighttime by hatching an owl from an egg and making it hoot. In a sombre moment, Snake comforts a woman in her dying moments with ludicrous ice skating puns. Snake taunts a horde of poisonous hamsters with cheese rations, and shoots them all dead so he can recover an MSX cartridge from a mousehole. This is the game for those who thought Metal Gear Solid's scented handkerchief and diarrhoea guard didn't go quite far enough.

I think a lot of the reason that this is one of the least played entries in the series is how close it plays to the sequels, while falling short of a lot of the stuff their fans take for granted. Despite all the 45 degree angles and how closely you perch yourself behind each corner, there's no wall-hugging here. You can call for advice on your radio, but your contacts' messages are very rarely relevant to your situation, and most of them barely ever answer your calls. So many of MGS1's big setpieces are ripped straight from this game, from fighting a former comrade in a Cyborg Ninja suit, to the HIND-D battle, to the stairway chase and elevator siege. It's all far more rudimentary in this, though, and not as justified by the surrounding scenario. I can see why many people would skip this and just go to the time they got these ideas right, but there's far more to the game than what MGS copied, and there's an appeal to seeing it all attempted on such early hardware.

As much as I love MGS1, a lot of the ideas that it iterated on fit better within MG2's structure. MGS is focused on keeping right on top of the narrative drive, and it tries its best to avoid backtracking, despite how much the surrounding design seems to suggest it. In MG2, you do have to keep track of armouries and ration locations. You'll probably have to come back to them to stock up before a boss. In MGS, the spawns are generous enough, and the combat is flexible enough that you can likely brute force your way through any encounter with enough ingenuity. MG2's approach is more tedious, but more consistent. The knowledge of the work associated with reacquiring health and ammo plays into the tension of avoiding detection. MG2 is a more bitter game, but an acquired taste appreciates that about it.

You know what? I kind of like backtracking. Maybe it's something I appreciate more in old games, when the new ones are busy forcing you through a bunch of single-purpose environments that their designers and artists broke their backs to give us, but I do enjoy feeling like I'm "in a place". Becoming familiar with the layout and the safe routes. It's part of what I like about the old Resident Evil games. Metal Gear 2 is an embarrassment of riches for backtracking fans. MGS1's structure is largely modelled on MG2, with its three main buildings, connecting bridge that gets blown up, and delivery vans to fasttravel between each of them. You don't really have much use for that ability in MGS, though. You never have any reason to go back from Sniper Wolf's snowfield outside the final building. I suspect the game's original plan was a little closer to Metal Gear 2, in that respect. Here, the first building is littered with locked doors you won't have access to until the very end of the game. There's no way to tell what level of key card you'll need to open them, but trial and error will get you there, eventually. The PAL Card heating/cooling bit is straight out of MG2, except it's far more brutal here. You have to traverse the entire map for it. It's divisive, and this may be Stockholm syndrome talking, but there's something I enjoy about it. I like reflecting on how far I've come, and finally accessing those mysterious rooms I've been held out of for so long.

Story and characters are much less of a draw in the first two games. There's moments, but few and far between. You get Gray Fox and Big Boss, but their motivations and backgrounds are far less well-developed than the following games would have you believe. Anyone who thought Snake and Meryl's relationship was rushed, adolescent, and perhaps even a little sexist, are not prepared for Holly White's dialogue. Look - It's the height of life-or-death instinct. These people don't know if they'll see tomorrow. They're incredibly horny. Cut them some slack.

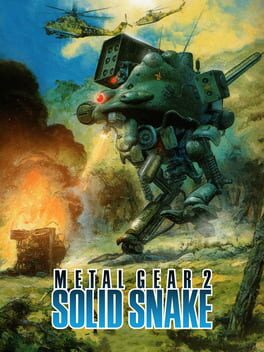

There's iconography in the game that's still unique to it. Metal Gear D's design came from kitbashing Kotobukiya military vehicle sets and drawing the resulting experiment as an in-game sprite afterwards. The game's cover art was drawn by model kit illustrator, Yoshiyuki Takani, and that 80s helicopter otaku vibe is all over the game. It's an entirely different vision of near-future war than the one KCEJ would explore little over a decade later. There's a style to the HUD and in-game tech that reminds me of the fanciful, far-out depictions of military tech in 80s films I grew up with on home-recorded VHS, like Commando and Short Circuit. Even just seeing Solid Snake in green combat fatigues is a little interesting, given the high-tech Sneaking Suits and Octocamo he's become associated with since then. As much of a Yoji Shinkawa stan as I've become, I still feel a little ennui from seeing his sprites in newer releases of the game, replacing the blatant Sean Connery and Albert Einstein portraits from the original. There's less visual consistency, with the rust and exposed wiring of the 1990 game. Metal Gear 2 is a very different idea of what this kind of top secret mission should look like, and it resonates with me more than the slick, semi-organic nanotech of the more futuristic titles.

The atmosphere in Metal Gear 2 is so rich, and that's largely owed to the soundtrack. The music is consistently brilliant, and researching this iteration of the Konami Kukeiha Club helps paint a picture of how much talent was in the team. Composers who went on to score games as diverse as Demon's Souls, Kirby's Epic Yarn, GuitarFreaks and Jikkyou Oshaberi Parodius, though it's likely Snatcher and Policenauts composer, Masahiro Ikariko, whose style is easiest to pick out. Kojima got a lot of shit on MGSV for abandoning David Hayter in favour of Hollywood talent, but I'd suggest the precedent was set when he sacrificed Konami's legendary in-house composers to butter up Harry Gregson-Williams on MGS2. That Escape from New York influence didn't stop at Snake Plisskin. The soundtrack is dripping with John Carpenter pulsing, electronic dread. I don't know if there are many people who Metal Gear 2 is an easy recommend for, but if you love MGS1 and Snatcher, I'd really encourage you to give the game an earnest effort.

The aesthetic isn't mere window dressing. It affects your attitude. Your acceptance of the task at hand. Slotting your rigid body in the enemies' blindspots, and entering undecorated boxy room after room of ammo pick-ups. It feels right, and it's the tone and atmosphere that convince you of that. You really want to play Metal Gear 2? Try it on an MSX with inch-high keys that give you carpal tunnel before the first boss.

I accept all of Metal Gear 2's flaws and readily present them at face value. I get a little anxious if I hear someone else is going to try playing the game. I doubt that anybody could see this awkward, ramshackle collection of ideas the same way I do. I can't deny my affection for it, though. It's the game that made me an MSX2 owner. To give it anything less than a perfect score would be disingenuous on my part. I first played it in the early 2000s, and I couldn't stop thinking about it as I started each new sequel, vibrating with glee if they ever did anything that so much as resembled something from this early entry. There's outposts and road markings in The Phantom Pain that mean the world to me. Back when in my early internet days, I used to frequent fansites from MSX-era Metal Gear fans, who would cover MGS as well. Somewhat reluctantly. Those guys were my heroes, and I still think of them as the authority on this stuff.

I can't shake my personal history with Metal Gear 2. I'm forever biased towards it. It's clear whenever I touch it that its effect on me hasn't diminished. It's still pretty much the definition of what I think of as a "real game". No polish, no concessions, just running around big square rooms and looking for stupid items. There's an elemental purity to it. Stick the cartridge in the slot and press the power button. This is The Game, and I fully expect you'll find it very boring.

I don't want to make Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake sound like an early prototype, or a demo recording of what would go on to become a classic song. It's an elaborate technical achievement in its own right. While other teams were struggling to draw multiple moving sprites on the fairly rudimentary MSX2 hardware, Kojima's team were creating a dense military base with distinct locations and patrolling enemies actively swarming off-screen. This was still 1990, and if Konami wanted a complicated action game, they'd ask their arcade or Famicom teams. The MSX was more associated with visual novel-style adventure games and conversions of early 80s arcade hits. They were underdogs, attempting the impossible. Metal Gear 2 on the MSX2 is like if they'd made Super Metroid on the Commodore 64 (and back with the schedules and budget constraints of the time, not some endless homebrew project).

I think I ought to talk about Metal Gear 1 a little. That was the result of a lot of compromises and inexperience. Hideo Kojima went into the games industry, excited to find a job that would allow him to express his own ideas and thoughts about the world around him. He was hired by Konami and dumped into the undesirable role of "planner". After some success working on Penguin Adventure, Kojima was tasked with designing a war game for the MSX. Kojima hated war, and it was a challenge to do intense action on the hardware. He decided to subvert the task he'd been given. Inspired by The Great Escape, he came up with a game where you try to avoid conflict and prevent the war from starting. Metal Gear was rushed and crude, coming from an inexperienced team. It controlled like an old Falcom RPG, and the stealth mechanics didn't go much further than having enemies who would fight you if you stood in front of them. There were some really great ideas in it, though. The cardboard boxes and remote-control missiles immediately became hallmarks of the series, though the sequels would make much better use of them.

Kojima went on to create Snatcher, which better allowed him to indulge in his passions of worldbuilding, science fiction, and tales of corporate deceit (a theme that has bitterly mirrored his own career). It also brought him closer to the home computer adventure games he was playing himself, like Yuji Horii's Portopia Serial Murder Case. He was able to explore human drama and complex, multi-layered conspiracy. He put more of himself into it, and each game he directed from that point on would carry a much stronger sense of its creator's voice. It was public demand that pushed him to revisit the Metal Gear concept, and it greatly benefitted from his newfound confidence and insight.

Much of Metal Gear 2's tone and logic is straight out of those 80s adventure games, only with a unique political bent. The age of nuclear deterrence has ended, but Zanzibar Land, a rogue state in Central Asia has been attacking international disposal facilities and amassing the unused warheads. Global oil shortages have caused an energy crisis, and the Czech biologist, Dr Kio Marv has developed a microbe capable of synthesizing petroleum to solve the problem. Dr Marv is kidnapped by Zanzibar Land soldiers, hoping to become the dominant nation in this era of peace. FOX-HOUND sends their top agent, Solid Snake, to recover the scientist and prevent the terrorists from launching a strike.

Metal Gear 2 is equal parts pet-project sincere and blurping moonman whimsy. It can often feel like someone bulked up their Warhammer army with GI Joes. You trick a guard into thinking it's nighttime by hatching an owl from an egg and making it hoot. In a sombre moment, Snake comforts a woman in her dying moments with ludicrous ice skating puns. Snake taunts a horde of poisonous hamsters with cheese rations, and shoots them all dead so he can recover an MSX cartridge from a mousehole. This is the game for those who thought Metal Gear Solid's scented handkerchief and diarrhoea guard didn't go quite far enough.

I think a lot of the reason that this is one of the least played entries in the series is how close it plays to the sequels, while falling short of a lot of the stuff their fans take for granted. Despite all the 45 degree angles and how closely you perch yourself behind each corner, there's no wall-hugging here. You can call for advice on your radio, but your contacts' messages are very rarely relevant to your situation, and most of them barely ever answer your calls. So many of MGS1's big setpieces are ripped straight from this game, from fighting a former comrade in a Cyborg Ninja suit, to the HIND-D battle, to the stairway chase and elevator siege. It's all far more rudimentary in this, though, and not as justified by the surrounding scenario. I can see why many people would skip this and just go to the time they got these ideas right, but there's far more to the game than what MGS copied, and there's an appeal to seeing it all attempted on such early hardware.

As much as I love MGS1, a lot of the ideas that it iterated on fit better within MG2's structure. MGS is focused on keeping right on top of the narrative drive, and it tries its best to avoid backtracking, despite how much the surrounding design seems to suggest it. In MG2, you do have to keep track of armouries and ration locations. You'll probably have to come back to them to stock up before a boss. In MGS, the spawns are generous enough, and the combat is flexible enough that you can likely brute force your way through any encounter with enough ingenuity. MG2's approach is more tedious, but more consistent. The knowledge of the work associated with reacquiring health and ammo plays into the tension of avoiding detection. MG2 is a more bitter game, but an acquired taste appreciates that about it.

You know what? I kind of like backtracking. Maybe it's something I appreciate more in old games, when the new ones are busy forcing you through a bunch of single-purpose environments that their designers and artists broke their backs to give us, but I do enjoy feeling like I'm "in a place". Becoming familiar with the layout and the safe routes. It's part of what I like about the old Resident Evil games. Metal Gear 2 is an embarrassment of riches for backtracking fans. MGS1's structure is largely modelled on MG2, with its three main buildings, connecting bridge that gets blown up, and delivery vans to fasttravel between each of them. You don't really have much use for that ability in MGS, though. You never have any reason to go back from Sniper Wolf's snowfield outside the final building. I suspect the game's original plan was a little closer to Metal Gear 2, in that respect. Here, the first building is littered with locked doors you won't have access to until the very end of the game. There's no way to tell what level of key card you'll need to open them, but trial and error will get you there, eventually. The PAL Card heating/cooling bit is straight out of MG2, except it's far more brutal here. You have to traverse the entire map for it. It's divisive, and this may be Stockholm syndrome talking, but there's something I enjoy about it. I like reflecting on how far I've come, and finally accessing those mysterious rooms I've been held out of for so long.

Story and characters are much less of a draw in the first two games. There's moments, but few and far between. You get Gray Fox and Big Boss, but their motivations and backgrounds are far less well-developed than the following games would have you believe. Anyone who thought Snake and Meryl's relationship was rushed, adolescent, and perhaps even a little sexist, are not prepared for Holly White's dialogue. Look - It's the height of life-or-death instinct. These people don't know if they'll see tomorrow. They're incredibly horny. Cut them some slack.

There's iconography in the game that's still unique to it. Metal Gear D's design came from kitbashing Kotobukiya military vehicle sets and drawing the resulting experiment as an in-game sprite afterwards. The game's cover art was drawn by model kit illustrator, Yoshiyuki Takani, and that 80s helicopter otaku vibe is all over the game. It's an entirely different vision of near-future war than the one KCEJ would explore little over a decade later. There's a style to the HUD and in-game tech that reminds me of the fanciful, far-out depictions of military tech in 80s films I grew up with on home-recorded VHS, like Commando and Short Circuit. Even just seeing Solid Snake in green combat fatigues is a little interesting, given the high-tech Sneaking Suits and Octocamo he's become associated with since then. As much of a Yoji Shinkawa stan as I've become, I still feel a little ennui from seeing his sprites in newer releases of the game, replacing the blatant Sean Connery and Albert Einstein portraits from the original. There's less visual consistency, with the rust and exposed wiring of the 1990 game. Metal Gear 2 is a very different idea of what this kind of top secret mission should look like, and it resonates with me more than the slick, semi-organic nanotech of the more futuristic titles.

The atmosphere in Metal Gear 2 is so rich, and that's largely owed to the soundtrack. The music is consistently brilliant, and researching this iteration of the Konami Kukeiha Club helps paint a picture of how much talent was in the team. Composers who went on to score games as diverse as Demon's Souls, Kirby's Epic Yarn, GuitarFreaks and Jikkyou Oshaberi Parodius, though it's likely Snatcher and Policenauts composer, Masahiro Ikariko, whose style is easiest to pick out. Kojima got a lot of shit on MGSV for abandoning David Hayter in favour of Hollywood talent, but I'd suggest the precedent was set when he sacrificed Konami's legendary in-house composers to butter up Harry Gregson-Williams on MGS2. That Escape from New York influence didn't stop at Snake Plisskin. The soundtrack is dripping with John Carpenter pulsing, electronic dread. I don't know if there are many people who Metal Gear 2 is an easy recommend for, but if you love MGS1 and Snatcher, I'd really encourage you to give the game an earnest effort.

The aesthetic isn't mere window dressing. It affects your attitude. Your acceptance of the task at hand. Slotting your rigid body in the enemies' blindspots, and entering undecorated boxy room after room of ammo pick-ups. It feels right, and it's the tone and atmosphere that convince you of that. You really want to play Metal Gear 2? Try it on an MSX with inch-high keys that give you carpal tunnel before the first boss.

I accept all of Metal Gear 2's flaws and readily present them at face value. I get a little anxious if I hear someone else is going to try playing the game. I doubt that anybody could see this awkward, ramshackle collection of ideas the same way I do. I can't deny my affection for it, though. It's the game that made me an MSX2 owner. To give it anything less than a perfect score would be disingenuous on my part. I first played it in the early 2000s, and I couldn't stop thinking about it as I started each new sequel, vibrating with glee if they ever did anything that so much as resembled something from this early entry. There's outposts and road markings in The Phantom Pain that mean the world to me. Back when in my early internet days, I used to frequent fansites from MSX-era Metal Gear fans, who would cover MGS as well. Somewhat reluctantly. Those guys were my heroes, and I still think of them as the authority on this stuff.

I can't shake my personal history with Metal Gear 2. I'm forever biased towards it. It's clear whenever I touch it that its effect on me hasn't diminished. It's still pretty much the definition of what I think of as a "real game". No polish, no concessions, just running around big square rooms and looking for stupid items. There's an elemental purity to it. Stick the cartridge in the slot and press the power button. This is The Game, and I fully expect you'll find it very boring.

2 Comments

@JimTheSchoolGirl Thanks very much. I think it requires a lot of tolerance and empathy for what the team were trying to achieve, and what they working with, but there's a bunch of cool, unique and amusing stuff to appreciate the game. I totally get it if it rubs folk cold.

JimTheSchoolGirl

6 months ago