Decoy_Octo

2 reviews liked by Decoy_Octo

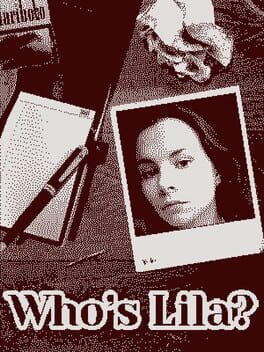

Who's Lila?

2022

Sometimes, not knowing is best.

Who's Lila is instantly recognizable to people who have seen even a screenshot of it due to its striking, 1-bit visuals combined with its emphasis on character faces that leads it to dedicate 40% of the screen to their portraits. For a reason, too: its main mechanic, aside from the standard point-and-click adventure toolkit, has the player manipulating the protagonist's face in order to imprint upon it an emotion to be perceived by other characters in the game.

See, William has a very hard time demonstrating emotions himself, but he tries to get by in his life. It just so happens that one of his friends, Tanya Kennedy, has disappeared, and the suspicion of foul play means that Will has a long day ahead of himself, with a lot of hard questions to answer. Multiple actors are at play, from Tanya's friends seeking her out, to the police digging around, a cult, conspiracies... and there are numerous endings to William's story depending on both the player's choices over the course of the day and their performance during conversations with others.

...and it all falls flat. As much as the face manipulation makes for a fascinating visual experience with its distorted, uncanny expressions, it's utilized somewhat poorly. This being a game with multiple endings, one would expect a focus on exploring different routes stemming from different NPC reactions, but that's not quite the case. There's few scenes in the game and even fewer occasions in which the outcome of the scene branches depending on the face William puts on, and when it does, it's almost always a matter of picking one of six correct emotions and passing the scene or not, with the game sometimes inelegantly telling the player to load the autosave because they messed up and are now stuck.

Add to that the face prompts unpredictably changing the line William is about to say, the facial expressions mechanic quickly turn into a gamified routine of trial-and-error, which only adds to the already large amount of friction inherent to playing Who's Lila. While the game's indieness is, at first, endearing, it quickly becomes irritating, with bugs, crashes and softlocks being a common sight, not to mention typos. Additionally, several questionable technical and creative decisions make it even harder to focus on the game instead of on its problems.

Who's Lila uses dithered visuals to render its scenes and presents them through fixed camera angles -- two techniques that look amazing in isolation but work against one another as they are used here. Dithering removes detail from an image (see note 1), reducing its clarity, which means it works best on high resolutions, where there's a surplus of detail, or when there's enough motion that more cues (shadows, the movement of objects relative to another) will allow a viewer to make out the picture.

As for fixed camera angles, they're not just about fixing the camera in a corner, like Who's Lila mostly does, but about employing cinematography to transmit feelings and establish a flow to the player's movement. So when using static cameras, in a scene made of low quality assets, whose game view occupies just over half the game window... well, there's a key for showing overlay icons on top of interactable objects around William, and suffice to say any player who doesn't want to object-hunt for several hours will be making extensive use of it.

Furthermore, there's an ARG element to the game. At certain points, the player is led to, on a real world browser, pore over a Twitter account, as well as visit websites from in-game URLs and download and opening PDFs that contain information needed to progress through the game. In itself, this is not terrible, since one can do all this on their phone without having to tap out of the game, but does come off as cheaply made and superfluous. What makes the ARG a pain is that part of the ARG involves installing a DLC for the game, the Daemon. That's a second executable that communicates with the main game's and triggers in-game events that wouldn't happen without it on.

It's a cute idea that ends up costing many players -- especially Steam Deck users, to which, by the way, Who's Lila is marked as Steam Deck Verified -- hours of tinkering for getting the executables to actually detect each other correctly (see note 2), and then forces playing in windowed mode so one can have both windows visible at the same time. There was no reason for it to be implemented this way other than the novelty factor, as one of the endings literally tells the player to download the Daemon, even showing the Steam Store link onscreen -- a moment in which it could have been introduced as an in-game mechanic and saved unlucky people the headache.

Mind you, this is not an optional component: a handful of endings, as well as the true ending, are impossible to achieve without the Daemon up and running. This also means that introducing the Daemon later would have also made onboarding new players much easier as they would not be immediately jumped by what, as they'll find out later, are alternate routes leading to some of the story's more obscure endings.

Friction is the keyword for Who's Lila, a game filled with interesting ideas but marred by a largely flawed execution that makes the experience as a whole harder to enjoy. In a sense, it's fitting that one of the main themes of a story is the obsession with unsolved mysteries and unknown quantities: Who's Lila seemed much more interesting from the small clips lying around the internet and the general vibes it gives off. All of that said, those ideas and vibes are here, and for those who'd like to check them out, by all means, there's far worse ways to spend money on Steam than handing it to a solo indie dev somewhere. Just be prepared for plenty of jank.

Note 1: Strictly speaking, it's not dithering that's removing detail, but the posterization step that precedes it and is required to achieve the sort of visuals seen here. In older hardware, which supported displaying less colors, dithering was employed to make it look like an image had more colors than it did -- nowadays, since computers support many more colors, to achieve that sort of retro visual, one must posterize the image first, then dither.

Note 2: A while after I finished the game, LoneEmissary and nicole.ham on the Steam Forums worked out a way to fix the game on Steam Deck (and probably any Arch-based distro) without having to mess with the system on a deeper level, so if you're an unlucky person who wishes to play Who's Lila on that platform, check their posts out.

Who's Lila is instantly recognizable to people who have seen even a screenshot of it due to its striking, 1-bit visuals combined with its emphasis on character faces that leads it to dedicate 40% of the screen to their portraits. For a reason, too: its main mechanic, aside from the standard point-and-click adventure toolkit, has the player manipulating the protagonist's face in order to imprint upon it an emotion to be perceived by other characters in the game.

See, William has a very hard time demonstrating emotions himself, but he tries to get by in his life. It just so happens that one of his friends, Tanya Kennedy, has disappeared, and the suspicion of foul play means that Will has a long day ahead of himself, with a lot of hard questions to answer. Multiple actors are at play, from Tanya's friends seeking her out, to the police digging around, a cult, conspiracies... and there are numerous endings to William's story depending on both the player's choices over the course of the day and their performance during conversations with others.

...and it all falls flat. As much as the face manipulation makes for a fascinating visual experience with its distorted, uncanny expressions, it's utilized somewhat poorly. This being a game with multiple endings, one would expect a focus on exploring different routes stemming from different NPC reactions, but that's not quite the case. There's few scenes in the game and even fewer occasions in which the outcome of the scene branches depending on the face William puts on, and when it does, it's almost always a matter of picking one of six correct emotions and passing the scene or not, with the game sometimes inelegantly telling the player to load the autosave because they messed up and are now stuck.

Add to that the face prompts unpredictably changing the line William is about to say, the facial expressions mechanic quickly turn into a gamified routine of trial-and-error, which only adds to the already large amount of friction inherent to playing Who's Lila. While the game's indieness is, at first, endearing, it quickly becomes irritating, with bugs, crashes and softlocks being a common sight, not to mention typos. Additionally, several questionable technical and creative decisions make it even harder to focus on the game instead of on its problems.

Who's Lila uses dithered visuals to render its scenes and presents them through fixed camera angles -- two techniques that look amazing in isolation but work against one another as they are used here. Dithering removes detail from an image (see note 1), reducing its clarity, which means it works best on high resolutions, where there's a surplus of detail, or when there's enough motion that more cues (shadows, the movement of objects relative to another) will allow a viewer to make out the picture.

As for fixed camera angles, they're not just about fixing the camera in a corner, like Who's Lila mostly does, but about employing cinematography to transmit feelings and establish a flow to the player's movement. So when using static cameras, in a scene made of low quality assets, whose game view occupies just over half the game window... well, there's a key for showing overlay icons on top of interactable objects around William, and suffice to say any player who doesn't want to object-hunt for several hours will be making extensive use of it.

Furthermore, there's an ARG element to the game. At certain points, the player is led to, on a real world browser, pore over a Twitter account, as well as visit websites from in-game URLs and download and opening PDFs that contain information needed to progress through the game. In itself, this is not terrible, since one can do all this on their phone without having to tap out of the game, but does come off as cheaply made and superfluous. What makes the ARG a pain is that part of the ARG involves installing a DLC for the game, the Daemon. That's a second executable that communicates with the main game's and triggers in-game events that wouldn't happen without it on.

It's a cute idea that ends up costing many players -- especially Steam Deck users, to which, by the way, Who's Lila is marked as Steam Deck Verified -- hours of tinkering for getting the executables to actually detect each other correctly (see note 2), and then forces playing in windowed mode so one can have both windows visible at the same time. There was no reason for it to be implemented this way other than the novelty factor, as one of the endings literally tells the player to download the Daemon, even showing the Steam Store link onscreen -- a moment in which it could have been introduced as an in-game mechanic and saved unlucky people the headache.

Mind you, this is not an optional component: a handful of endings, as well as the true ending, are impossible to achieve without the Daemon up and running. This also means that introducing the Daemon later would have also made onboarding new players much easier as they would not be immediately jumped by what, as they'll find out later, are alternate routes leading to some of the story's more obscure endings.

Friction is the keyword for Who's Lila, a game filled with interesting ideas but marred by a largely flawed execution that makes the experience as a whole harder to enjoy. In a sense, it's fitting that one of the main themes of a story is the obsession with unsolved mysteries and unknown quantities: Who's Lila seemed much more interesting from the small clips lying around the internet and the general vibes it gives off. All of that said, those ideas and vibes are here, and for those who'd like to check them out, by all means, there's far worse ways to spend money on Steam than handing it to a solo indie dev somewhere. Just be prepared for plenty of jank.

Note 1: Strictly speaking, it's not dithering that's removing detail, but the posterization step that precedes it and is required to achieve the sort of visuals seen here. In older hardware, which supported displaying less colors, dithering was employed to make it look like an image had more colors than it did -- nowadays, since computers support many more colors, to achieve that sort of retro visual, one must posterize the image first, then dither.

Note 2: A while after I finished the game, LoneEmissary and nicole.ham on the Steam Forums worked out a way to fix the game on Steam Deck (and probably any Arch-based distro) without having to mess with the system on a deeper level, so if you're an unlucky person who wishes to play Who's Lila on that platform, check their posts out.

Final Fantasy XVI

2023

I considered strongly putting together a long-form critique of this game, but the most damning statement I could possibly make about Final Fantasy XVI is that I truly don't think it's worth it. The ways in which I think this game is bad are not unique or interesting: it is bad in the same way the vast majority of these prestige Sony single-player exclusives are. Its failures are common, predictable, and depressingly endemic. It is bad because it hates women, it is bad because it treats it's subject matter with an aggressive lack of care or interest, it is bad because it's imagination is as narrow and constrained as it's level design. But more than anything else, it is bad because it only wants to be Good.

Oxymoronic a statement as it might appear, this is core to the game's failings to me. People who make games generally want to make good games, of course, but paired with that there is an intent, an interest, an idea that seeks to be communicated, that the eloquence with which it professes its aesthetic, thematic, or mechanical goals will produce the quality it seeks. Final Fantasy XVI may have such goals, but they are supplicant to its desire to be liked, and so, rather than plant a flag of its own, it stitches together one from fabric pillaged from the most immediate eikons of popularity and quality - A Song of Ice and Fire, God of War, Demon Slayer, Devil May Cry - desperately begging to be liked by cloaking itself in what many people already do, needing to be loved in the way those things are, without any of the work or vision of its influences, and without any charisma of its own. Much like the patch and DLC content for Final Fantasy XV, it's a reactionary and cloying work that contorts itself into a shape it thinks people will love, rather than finding a unique self to be.

From the aggressively self-serious tone that embraces wholeheartedly the aesthetics of Prestige Fantasy Television with all its fucks and shits and incest and Grim Darkness to let you know that This Isn't Your Daddy's Final Fantasy, without actually being anywhere near as genuinely Dark, sad, or depressing as something like XV, from combat that borrows the surface-level signifiers of Devil May Cry combat - stingers, devil bringers, enemy step - but without any actual opposition or reaction of that series' diverse and reactive enemy set and thoughtful level design, or the way there's a episode of television-worth of lectures from a character explaining troop movements and map markers that genuinely do not matter in any way in order to make you feel like you're experiencing a well thought-out and materially concerned political Serious Fantasy, Final Fantasy XVI is pure wafer-thin illusion; all the surface from it's myriad influences but none of the depth or nuance, a greatest hits album from a band with no voice to call their own, an algorithmically generated playlist of hits that tunelessly resound with nothing. It looks like Devil May Cry, but it isn't - Devil May Cry would ask more of you than dodging one attack at a time while you perform a particularly flashy MMO rotation. It looks like A Song of Ice and Fire, but it isn't - without Martin's careful historical eye and materialist concerns, the illusion that this comes even within striking distance of that flawed work shatters when you think about the setting for more than a moment.

In fairness, Final Fantasy XVI does bring more than just the surface level into its world: it also brings with it the nastiest and ugliest parts of those works into this one, replicated wholeheartedly as Aesthetic, bereft of whatever semblance of texture and critique may have once been there. Benedikta Harman might be the most disgustingly treated woman in a recent work of fiction, the seemingly uniform AAA Game misogyny of evil mothers and heroic, redeemable fathers is alive and well, 16's version of this now agonizingly tired cliche going farther even than games I've railed against for it in the past, which all culminates in a moment where three men tell the female lead to stay home while they go and fight (despite one of those men being a proven liability to himself and others when doing the same thing he is about to go and do again, while she is not), she immediately acquiesces, and dutifully remains in the proverbial kitchen. Something that thinks so little of women is self-evidently incapable of meaningfully tackling any real-world issue, something Final Fantasy XVI goes on to decisively prove, with its story of systemic evils defeated not with systemic criticism, but with Great, Powerful Men, a particularly tiresome kind of rugged bootstrap individualism that seeks to reduce real-world evils to shonen enemies for the Special Man with Special Powers to defeat on his lonesome. It's an attempt to discuss oppression and racism that would embarrass even the other shonen media it is clearly closer in spirit to than the dark fantasy political epic it wears the skin of. In a world where the power fantasy of the shonen superhero is sacrosanct over all other concerns, it leads to a conclusion as absurd and fundamentally unimaginative as shonen jump's weakest scripts: the only thing that can stop a Bad Guy with an Eikon is a Good Guy with an Eikon.

In borrowing the aesthetics of the dark fantasy - and Matsuno games - it seeks to emulate, but without the nuance, FF16 becomes a game where the perspective of the enslaved is almost completely absent (Clive's period as a slave might as well not have occurred for all it impacts his character), and the power of nobility is Good when it is wielded by Good Hands like Lord Rosfield, a slave owner who, despite owning the clearly abused character who serves as our introduction to the bearers, is eulogized completely uncritically by the script, until a final side quest has a character claim that he was planning to free the slaves all along...alongside a letter where Lord Rosfield discusses his desire to "put down the savages". I've never seen attempted slave owner apologia that didn't reveal its virulent underlying racism, and this is no exception. In fact, any time the game attempts to put on a facade of being about something other than The Shonen Hero battling other Kamen Riders for dominance, it crumbles nigh-immediately; when Final Fantasy 16 makes its overtures towards the Power of Friendship, it rings utterly false and hollow: Clive's friends are not his power. His power is his power.

The only part of the game that truly spoke to me was the widely-derided side-quests, which offer a peek into a more compelling story: the story of a man doing the work to build and maintain a community, contributing to both the material and emotional needs of a commune that attempts to exist outside the violence of society. As tedious as these sidequests are - and as agonizing as their pacing so often is - it's the only part of this game where it felt like I was engaging with an idea. But ultimately, even this is annihilated by the game's bootstrap nonsense - that being that the hideaway is funded and maintained by the wealthy and influential across the world, the direct beneficiaries and embodiments of the status quo funding what their involvement reveals to be an utterly illusionary attempt to escape it, rendering what could be an effective exploration of what building a new idea of a community practically looks like into something that could be good neighbors with Galt's Gulch.

In a series that is routinely deeply rewarding for me to consider, FF16 stands as perhaps its most shallow, underwritten, and vacuous entry in decades. All games are ultimately illusions, of course: we're all just moving data around spreadsheets, at the end of the day. But - as is the modern AAA mode de jour - 16 is the result of the careful subtraction of texture from the experience of a game, the removal of any potential frictions and frustrations, but further even than that, it is the removal of personality, of difference, it is the attempt to make make the smoothest, most likable affect possible to the widest number of people possible. And, just like with its AAA brethren, it has almost nothing to offer me. It is the affect of Devil May Cry without its texture, the affect of Game of Thrones without even its nuance, and the affect of Final Fantasy without its soul.

Final Fantasy XVI is ultimately a success. It sought out to be Good, in the way a PS5 game like this is Good, and succeeded. And in so doing, it closed off any possibility that it would ever reach me.

It doesn’t really surprise me that each positive sentiment I have seen on Final Fantasy XVI is followed by an exclamation of derision over the series’ recent past. Whether the point of betrayal and failure was in XV, or with XIII, or even as far back as VIII, the rhetorical move is well and truly that Final Fantasy has been Bad, and with XVI, it is good again. Unfortunately, as someone who thought Final Fantasy has Been Good, consistently, throughout essentially the entire span of it's existence, I find myself on the other side of this one.

Final Fantasy XV convinced me that I could still love video games when I thought, for a moment, that I might not. That it was still possible to make games on this scale that were idiosyncratic, personal, and deeply human, even in the awful place the video game industry is in.

Final Fantasy XVI convinced me that it isn't.

Oxymoronic a statement as it might appear, this is core to the game's failings to me. People who make games generally want to make good games, of course, but paired with that there is an intent, an interest, an idea that seeks to be communicated, that the eloquence with which it professes its aesthetic, thematic, or mechanical goals will produce the quality it seeks. Final Fantasy XVI may have such goals, but they are supplicant to its desire to be liked, and so, rather than plant a flag of its own, it stitches together one from fabric pillaged from the most immediate eikons of popularity and quality - A Song of Ice and Fire, God of War, Demon Slayer, Devil May Cry - desperately begging to be liked by cloaking itself in what many people already do, needing to be loved in the way those things are, without any of the work or vision of its influences, and without any charisma of its own. Much like the patch and DLC content for Final Fantasy XV, it's a reactionary and cloying work that contorts itself into a shape it thinks people will love, rather than finding a unique self to be.

From the aggressively self-serious tone that embraces wholeheartedly the aesthetics of Prestige Fantasy Television with all its fucks and shits and incest and Grim Darkness to let you know that This Isn't Your Daddy's Final Fantasy, without actually being anywhere near as genuinely Dark, sad, or depressing as something like XV, from combat that borrows the surface-level signifiers of Devil May Cry combat - stingers, devil bringers, enemy step - but without any actual opposition or reaction of that series' diverse and reactive enemy set and thoughtful level design, or the way there's a episode of television-worth of lectures from a character explaining troop movements and map markers that genuinely do not matter in any way in order to make you feel like you're experiencing a well thought-out and materially concerned political Serious Fantasy, Final Fantasy XVI is pure wafer-thin illusion; all the surface from it's myriad influences but none of the depth or nuance, a greatest hits album from a band with no voice to call their own, an algorithmically generated playlist of hits that tunelessly resound with nothing. It looks like Devil May Cry, but it isn't - Devil May Cry would ask more of you than dodging one attack at a time while you perform a particularly flashy MMO rotation. It looks like A Song of Ice and Fire, but it isn't - without Martin's careful historical eye and materialist concerns, the illusion that this comes even within striking distance of that flawed work shatters when you think about the setting for more than a moment.

In fairness, Final Fantasy XVI does bring more than just the surface level into its world: it also brings with it the nastiest and ugliest parts of those works into this one, replicated wholeheartedly as Aesthetic, bereft of whatever semblance of texture and critique may have once been there. Benedikta Harman might be the most disgustingly treated woman in a recent work of fiction, the seemingly uniform AAA Game misogyny of evil mothers and heroic, redeemable fathers is alive and well, 16's version of this now agonizingly tired cliche going farther even than games I've railed against for it in the past, which all culminates in a moment where three men tell the female lead to stay home while they go and fight (despite one of those men being a proven liability to himself and others when doing the same thing he is about to go and do again, while she is not), she immediately acquiesces, and dutifully remains in the proverbial kitchen. Something that thinks so little of women is self-evidently incapable of meaningfully tackling any real-world issue, something Final Fantasy XVI goes on to decisively prove, with its story of systemic evils defeated not with systemic criticism, but with Great, Powerful Men, a particularly tiresome kind of rugged bootstrap individualism that seeks to reduce real-world evils to shonen enemies for the Special Man with Special Powers to defeat on his lonesome. It's an attempt to discuss oppression and racism that would embarrass even the other shonen media it is clearly closer in spirit to than the dark fantasy political epic it wears the skin of. In a world where the power fantasy of the shonen superhero is sacrosanct over all other concerns, it leads to a conclusion as absurd and fundamentally unimaginative as shonen jump's weakest scripts: the only thing that can stop a Bad Guy with an Eikon is a Good Guy with an Eikon.

In borrowing the aesthetics of the dark fantasy - and Matsuno games - it seeks to emulate, but without the nuance, FF16 becomes a game where the perspective of the enslaved is almost completely absent (Clive's period as a slave might as well not have occurred for all it impacts his character), and the power of nobility is Good when it is wielded by Good Hands like Lord Rosfield, a slave owner who, despite owning the clearly abused character who serves as our introduction to the bearers, is eulogized completely uncritically by the script, until a final side quest has a character claim that he was planning to free the slaves all along...alongside a letter where Lord Rosfield discusses his desire to "put down the savages". I've never seen attempted slave owner apologia that didn't reveal its virulent underlying racism, and this is no exception. In fact, any time the game attempts to put on a facade of being about something other than The Shonen Hero battling other Kamen Riders for dominance, it crumbles nigh-immediately; when Final Fantasy 16 makes its overtures towards the Power of Friendship, it rings utterly false and hollow: Clive's friends are not his power. His power is his power.

The only part of the game that truly spoke to me was the widely-derided side-quests, which offer a peek into a more compelling story: the story of a man doing the work to build and maintain a community, contributing to both the material and emotional needs of a commune that attempts to exist outside the violence of society. As tedious as these sidequests are - and as agonizing as their pacing so often is - it's the only part of this game where it felt like I was engaging with an idea. But ultimately, even this is annihilated by the game's bootstrap nonsense - that being that the hideaway is funded and maintained by the wealthy and influential across the world, the direct beneficiaries and embodiments of the status quo funding what their involvement reveals to be an utterly illusionary attempt to escape it, rendering what could be an effective exploration of what building a new idea of a community practically looks like into something that could be good neighbors with Galt's Gulch.

In a series that is routinely deeply rewarding for me to consider, FF16 stands as perhaps its most shallow, underwritten, and vacuous entry in decades. All games are ultimately illusions, of course: we're all just moving data around spreadsheets, at the end of the day. But - as is the modern AAA mode de jour - 16 is the result of the careful subtraction of texture from the experience of a game, the removal of any potential frictions and frustrations, but further even than that, it is the removal of personality, of difference, it is the attempt to make make the smoothest, most likable affect possible to the widest number of people possible. And, just like with its AAA brethren, it has almost nothing to offer me. It is the affect of Devil May Cry without its texture, the affect of Game of Thrones without even its nuance, and the affect of Final Fantasy without its soul.

Final Fantasy XVI is ultimately a success. It sought out to be Good, in the way a PS5 game like this is Good, and succeeded. And in so doing, it closed off any possibility that it would ever reach me.

It doesn’t really surprise me that each positive sentiment I have seen on Final Fantasy XVI is followed by an exclamation of derision over the series’ recent past. Whether the point of betrayal and failure was in XV, or with XIII, or even as far back as VIII, the rhetorical move is well and truly that Final Fantasy has been Bad, and with XVI, it is good again. Unfortunately, as someone who thought Final Fantasy has Been Good, consistently, throughout essentially the entire span of it's existence, I find myself on the other side of this one.

Final Fantasy XV convinced me that I could still love video games when I thought, for a moment, that I might not. That it was still possible to make games on this scale that were idiosyncratic, personal, and deeply human, even in the awful place the video game industry is in.

Final Fantasy XVI convinced me that it isn't.