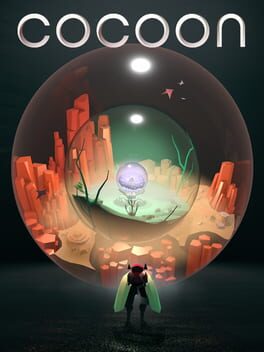

Cocoon operates with two opposite paradigms at the same time. Aesthetically, it is one of the most deliberately alien experiences in recent memory, stripped almost entirely from the usual layers of anthropomorphism that structure the vast majority of video games. While there may be parts of Cocoon’s worlds that were inspired by earthly shapes and figures, their assemblage escapes every attempt of categorization. You’ll traverse natural landscapes like desolated canyons or boundless swamps that are honeycombed by artificial geometric forms. Futuristic artifacts are scattered across these wastelands like remnants of long-lost civilizations, without showing any signs of decay. Instead, the most advanced technologies are often seamlessly integrated into their surroundings, appearing as nothing more than a natural expansion of the domestic life-forms. Most of the alien creatures seem to be modeled after various types of insects, albeit with fluid boundaries to synthetic life on one side and inorganic matter on the other. No words are spoken throughout the entire game to try to explain those beings, though I doubt that the categories familiar to our language would be sufficient to adequately describe them.

To give just one example: There are these tiny, pyramid-shaped flying things that temporarily accompany you throughout the game and are used to open certain barriers, thus resembling a sort of remote control. But the same robotic assistants are created out of some amorphic floating liquid that shapes into an amber-like crystal before being shattered to give “birth” to them like a fossilized insect. And at some point, other floating things appear that can trap your little companions with a sticky substance, as if they are carnivorous plants that act as natural enemies, even though they can themselves be remotely controlled on predetermined paths by the player character. Cocoon constantly undermines any effort to adequately organize its sights and sounds, most notably with its central feature of traveling between worlds within worlds, a mechanic that literally forces you to inverse your previous sense of proportions and causation on a routine basis.

Mechanically, however, Cocoon is translucently unambiguous. As confusing as the jump into and out of the different worlds may be visually, it rarely leaves you stranded about what to do next. Progression is completely linear, with only the occasional branching path that leads to a dead end after a few steps. Every new problem is presented in a way that makes it immediately obvious what you need to achieve, just as all the tools and obstacles on your way are distinctly highlighted. Consider again your little pyramid-shaped companions. A beam of light shines from the tip of the pyramid which automatically points you to your next objective. Once they reach their corresponding obstacle, a little animation is triggered which makes the obstacle glow as well before it starts moving. The same beam starts to flicker when they get close to their enemy. Finally, they disappear again as soon as their purpose is fulfilled. Although it is never explained what this thing is or why it works the way it does, the question how it works never really arises.

The same is true for every single element in the game: Buttons open doors or move platforms, pressure plates need a weight on them to stay activated, pipes are used to transport orbs etc. And since there is only one action button, you are never in doubt about how to interact with the various objects as well. Even the bosses reliably follow a pre-established rulebook. Every boss first introduces itself in a scripted sequence, before challenging you at the end of its respective segment where it takes every precaution to telegraph its attacks and reveal its weak spot as clearly as possible during the fight. I never got hit on my first try in any of these encounters, which pretty much never happened to me before. In short, you have any prior experience with puzzles from other games, there are almost no surprises here. The game isn’t even all that difficult. Puzzles might technically get very complex and abstract towards the end, but they are always structured in a way that splits the challenges up into multiple smaller segments with only a handful of variables to work with. For most of the playtime, the solution presents itself almost as naturally as all the other elements.

By all accounts, these two contradictory approaches to aesthetics and gameplay should all but negate each other. Instead, the unique quality of Cocoon arises from the tension between them. It captures an experience of immense uncertainty about the fundamental conditions of the world – what things are and why they exist –, but at the same time gives you an almost instinctive understanding of how to work with them. Crucially, most puzzles play out less stimulating than arduous. This is by no means meant as a criticism. It simply describes the basic condition of the character, who is constantly working by carrying around these orbs more than twice their size on their back, taking part in a process where the next step is always logical enough to take it almost automatically, while both the originating cause and ultimate goal of your actions are infinitely removed from your grasp – along with all the curiosity and excitement as well as uneasiness and distress this process implies. The only thing that was somewhat clear to me throughout the adventure was that my actions were somehow driving forward some kind of evolutionary process. But whose evolution I was contributing to or to what ends is left almost completely open to speculation. Your role is just to bear witness to a gradual accumulation of energy and power, which progressively involves everything from the tiniest insects to the most elemental forces of the universe.

__________________

More puzzle game reviews

Chants of Sennaar

Hitman GO

Mole Mania

To give just one example: There are these tiny, pyramid-shaped flying things that temporarily accompany you throughout the game and are used to open certain barriers, thus resembling a sort of remote control. But the same robotic assistants are created out of some amorphic floating liquid that shapes into an amber-like crystal before being shattered to give “birth” to them like a fossilized insect. And at some point, other floating things appear that can trap your little companions with a sticky substance, as if they are carnivorous plants that act as natural enemies, even though they can themselves be remotely controlled on predetermined paths by the player character. Cocoon constantly undermines any effort to adequately organize its sights and sounds, most notably with its central feature of traveling between worlds within worlds, a mechanic that literally forces you to inverse your previous sense of proportions and causation on a routine basis.

Mechanically, however, Cocoon is translucently unambiguous. As confusing as the jump into and out of the different worlds may be visually, it rarely leaves you stranded about what to do next. Progression is completely linear, with only the occasional branching path that leads to a dead end after a few steps. Every new problem is presented in a way that makes it immediately obvious what you need to achieve, just as all the tools and obstacles on your way are distinctly highlighted. Consider again your little pyramid-shaped companions. A beam of light shines from the tip of the pyramid which automatically points you to your next objective. Once they reach their corresponding obstacle, a little animation is triggered which makes the obstacle glow as well before it starts moving. The same beam starts to flicker when they get close to their enemy. Finally, they disappear again as soon as their purpose is fulfilled. Although it is never explained what this thing is or why it works the way it does, the question how it works never really arises.

The same is true for every single element in the game: Buttons open doors or move platforms, pressure plates need a weight on them to stay activated, pipes are used to transport orbs etc. And since there is only one action button, you are never in doubt about how to interact with the various objects as well. Even the bosses reliably follow a pre-established rulebook. Every boss first introduces itself in a scripted sequence, before challenging you at the end of its respective segment where it takes every precaution to telegraph its attacks and reveal its weak spot as clearly as possible during the fight. I never got hit on my first try in any of these encounters, which pretty much never happened to me before. In short, you have any prior experience with puzzles from other games, there are almost no surprises here. The game isn’t even all that difficult. Puzzles might technically get very complex and abstract towards the end, but they are always structured in a way that splits the challenges up into multiple smaller segments with only a handful of variables to work with. For most of the playtime, the solution presents itself almost as naturally as all the other elements.

By all accounts, these two contradictory approaches to aesthetics and gameplay should all but negate each other. Instead, the unique quality of Cocoon arises from the tension between them. It captures an experience of immense uncertainty about the fundamental conditions of the world – what things are and why they exist –, but at the same time gives you an almost instinctive understanding of how to work with them. Crucially, most puzzles play out less stimulating than arduous. This is by no means meant as a criticism. It simply describes the basic condition of the character, who is constantly working by carrying around these orbs more than twice their size on their back, taking part in a process where the next step is always logical enough to take it almost automatically, while both the originating cause and ultimate goal of your actions are infinitely removed from your grasp – along with all the curiosity and excitement as well as uneasiness and distress this process implies. The only thing that was somewhat clear to me throughout the adventure was that my actions were somehow driving forward some kind of evolutionary process. But whose evolution I was contributing to or to what ends is left almost completely open to speculation. Your role is just to bear witness to a gradual accumulation of energy and power, which progressively involves everything from the tiniest insects to the most elemental forces of the universe.

__________________

More puzzle game reviews

Chants of Sennaar

Hitman GO

Mole Mania