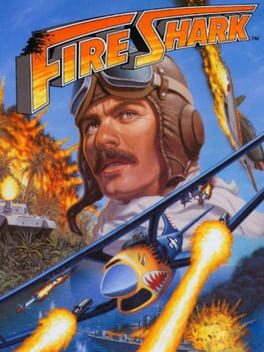

An expanded game of Same! Same! Same!

In the arcade version, one summer night in 1991, an enemy fleet known as the Strange Fleet approached a small island of the Mediterranean Sea. When it arrived, very few saw the Strange Fleet. Two years later, while the Stranger Fleet expanded itself, it created a world war. It is unknown by everyone around the world who noticed the attacks of the Strange Fleet. As the Strange Fleet continues their assault, many against them cried "Fire Shark! Fire Shark! It's time to take off!! Beat them for our sake. Go! Go! Fire Shark!"

Reviews View More

So, fun fact, at one point at the beggining of the 2020s I stopped playing videogames. My friend from Spain was telling me all about these more modern games that were masterclasses at artistic expression and brought something of phillosphical and personal use for the player and I was there, thinking gameplay was the only thing that mattered. I didn't have a good PC to play more modern titles, I only had a phone which filled up with memory pretty quickly so I couldn't play native games on it (and I still won't) because deleting them to have space for everyday life meant deleting its save files.

That's why since I had a phone with android, I always used emulators, playing games from the 16 bit generation (and the GBA) and below as that was the most I could run. If anything happened, I would just move the save files to PC and then back, I could transfer them between devices and still have a record of my memories with the games.

So I ended up building a criteria as an excuse to playing these games, now I don't think a game should neccesarily be "fun" as art can communicate things in other media like film without serving as a way of escapism, but back then I only had Youtube channels like Game Sack or the AVGN or the stupid Console Wars to build up ways to analyze games. My go to review channel was Implant Games, I still have respect for him, as he went into extreme detail in the games he covered showing the inner workings of level design.

"Oh... So that's where games can be like art!" I thought, "if the games I played can't reach the elegance of a Bergman film or the depht of a Dostoievski novel, then it's like architechture, there has to be a very well planned construction for it to be great, and not only that, it's not held back by the physics of the real world!", since few games I had played up to that point tried to handle story or themes and my memory of having played the beautiful expression that was the Mother trilogy, which didn't mind having a boring section where you were a factory worker just to portray how boring it was in real life, was becoming ever more distant, as an exception to the rule.

But then I played more games, all retro, and then more games, all retro, and then more games, all retro. Eventually I bought the phone I'm writing this in and my brother bought a better computer. And then while my friend from Spain started seeing games as art, depending on expression and telling me about modern indie titles, I came up with Toaplan's shooter games.

"Something is missing" I thought. They were fun to play with, they were competently designed, but why were they getting progressively more uninteresting as I played them from the older to the newer if I was experiencing how the design became progressively better at being "more fun"? Why wasn't I having fun? Why did I feel I was wasting my time? "This can be good level design, but I feel I have seen this done before in other games. It's just copying a formula to have fun with, but what makes this stand out from the other things I've played?"

That's when I realized, if I removed all the aesthetics and only played a game with the graphics of a Magnavox Oddyssey, I would see that good gameplay, the only pillar I thought that could be the support for the entire medium, would leave me with something that didn't automatically make something stand out, something that communicated anything.

"But then what makes architechture be considered art?" I asked myself, trying to go to the roots of the problem. And then I realized, in architechture, you could either have something as expressive as Antonio Gaudi's buildings, which wasn't just the infrastructure, it was also how he stylized the buildings, what he put inside, what mattered and expressed something, or else you could end up having just a dumb office building, which don't express anything but do have a practical use.

So videogames if looked like I looked at them weren't trying to achieve Gaudi, what were them? I thought they were made for fun, so I tried to find anything to give them the prestige that rivaled other forms of art just through game design alone. But then it came to mind, they are like those amusement parks. They weren't expressing anything through gameplay alone, they wouldn't contribute anything to a person other than a more elaborated form of escapism just to have a momentary thrill. A game only focused on gameplay to have fun was no more expressive than a roller coaster with the most varied and amusing tracks at best and a simple duck shooting game to win prizes at worst.

And then it hit me, I didn't have anything worthwile to talk about with my friend from Spain. I had been mostly on amusement park rides my whole videogame life, playing only retro games with very few things I could bring about which could be beneficial for self improvement or just to talk about greater scope topics. I only had Earthbound to offer, and that's why it's still my favourite game just like 2001 is my favourite movie even if they are not objectively the best, it's what introduced me into a greater scope.

I finished playing Toaplan's Twin Hawk, one of the most generic games I've ever played, and since I realized videogames wouldn't contribute anything more the way I experienced them, I just took a break for a few months. In a way I should be thankful to that boring ass game, since it allowed me to change my paradigm at how I approach gaming. Talking with my friend from Spain about the potential for exploring something more made me look for interesting and in-deep ways games could be used to communicate things (like how "That Dragon, Cancer" uses the interactive medium itself to present a fun time so that the latter exploration on the characters' suffering to share how one goes through a tough situation can be more arresting), or even if they didn't and were made just to have fun just like a summer blockbuster, to see what personality it conveyed (today I can think of Cuphead which I recently played: even if it grabbed from other things for its aesthetic, some of the bosses had backstories which could be infered just by the way they move and the attacks they use, by incorporating techniques from the animated medium). And then I came back, enjoying videogames more than ever, seeing both their potential and intriguing depht; and a more colorful and inventive look to their escapist side, a rollercoaster which wasn't just for fun but also had something only portrayed by its own identity.

-----

The Toaplan vertical scrolling shooters I've played until now had very little of that personality, and that's what made me realize gameplay by itself wasn't enough. They are just a bunch of planes fighting other planes with none of Compile's more cinematic camera movements to at least convey more adrenaline. Fire Shark is like that, though at least it shows a tiny thing that makes it a bit less generic than Twin Hawk. At the start of every level there are a bunch of soldiers who are doing funny background events. And yeah, that's it.

That's why since I had a phone with android, I always used emulators, playing games from the 16 bit generation (and the GBA) and below as that was the most I could run. If anything happened, I would just move the save files to PC and then back, I could transfer them between devices and still have a record of my memories with the games.

So I ended up building a criteria as an excuse to playing these games, now I don't think a game should neccesarily be "fun" as art can communicate things in other media like film without serving as a way of escapism, but back then I only had Youtube channels like Game Sack or the AVGN or the stupid Console Wars to build up ways to analyze games. My go to review channel was Implant Games, I still have respect for him, as he went into extreme detail in the games he covered showing the inner workings of level design.

"Oh... So that's where games can be like art!" I thought, "if the games I played can't reach the elegance of a Bergman film or the depht of a Dostoievski novel, then it's like architechture, there has to be a very well planned construction for it to be great, and not only that, it's not held back by the physics of the real world!", since few games I had played up to that point tried to handle story or themes and my memory of having played the beautiful expression that was the Mother trilogy, which didn't mind having a boring section where you were a factory worker just to portray how boring it was in real life, was becoming ever more distant, as an exception to the rule.

But then I played more games, all retro, and then more games, all retro, and then more games, all retro. Eventually I bought the phone I'm writing this in and my brother bought a better computer. And then while my friend from Spain started seeing games as art, depending on expression and telling me about modern indie titles, I came up with Toaplan's shooter games.

"Something is missing" I thought. They were fun to play with, they were competently designed, but why were they getting progressively more uninteresting as I played them from the older to the newer if I was experiencing how the design became progressively better at being "more fun"? Why wasn't I having fun? Why did I feel I was wasting my time? "This can be good level design, but I feel I have seen this done before in other games. It's just copying a formula to have fun with, but what makes this stand out from the other things I've played?"

That's when I realized, if I removed all the aesthetics and only played a game with the graphics of a Magnavox Oddyssey, I would see that good gameplay, the only pillar I thought that could be the support for the entire medium, would leave me with something that didn't automatically make something stand out, something that communicated anything.

"But then what makes architechture be considered art?" I asked myself, trying to go to the roots of the problem. And then I realized, in architechture, you could either have something as expressive as Antonio Gaudi's buildings, which wasn't just the infrastructure, it was also how he stylized the buildings, what he put inside, what mattered and expressed something, or else you could end up having just a dumb office building, which don't express anything but do have a practical use.

So videogames if looked like I looked at them weren't trying to achieve Gaudi, what were them? I thought they were made for fun, so I tried to find anything to give them the prestige that rivaled other forms of art just through game design alone. But then it came to mind, they are like those amusement parks. They weren't expressing anything through gameplay alone, they wouldn't contribute anything to a person other than a more elaborated form of escapism just to have a momentary thrill. A game only focused on gameplay to have fun was no more expressive than a roller coaster with the most varied and amusing tracks at best and a simple duck shooting game to win prizes at worst.

And then it hit me, I didn't have anything worthwile to talk about with my friend from Spain. I had been mostly on amusement park rides my whole videogame life, playing only retro games with very few things I could bring about which could be beneficial for self improvement or just to talk about greater scope topics. I only had Earthbound to offer, and that's why it's still my favourite game just like 2001 is my favourite movie even if they are not objectively the best, it's what introduced me into a greater scope.

I finished playing Toaplan's Twin Hawk, one of the most generic games I've ever played, and since I realized videogames wouldn't contribute anything more the way I experienced them, I just took a break for a few months. In a way I should be thankful to that boring ass game, since it allowed me to change my paradigm at how I approach gaming. Talking with my friend from Spain about the potential for exploring something more made me look for interesting and in-deep ways games could be used to communicate things (like how "That Dragon, Cancer" uses the interactive medium itself to present a fun time so that the latter exploration on the characters' suffering to share how one goes through a tough situation can be more arresting), or even if they didn't and were made just to have fun just like a summer blockbuster, to see what personality it conveyed (today I can think of Cuphead which I recently played: even if it grabbed from other things for its aesthetic, some of the bosses had backstories which could be infered just by the way they move and the attacks they use, by incorporating techniques from the animated medium). And then I came back, enjoying videogames more than ever, seeing both their potential and intriguing depht; and a more colorful and inventive look to their escapist side, a rollercoaster which wasn't just for fun but also had something only portrayed by its own identity.

-----

The Toaplan vertical scrolling shooters I've played until now had very little of that personality, and that's what made me realize gameplay by itself wasn't enough. They are just a bunch of planes fighting other planes with none of Compile's more cinematic camera movements to at least convey more adrenaline. Fire Shark is like that, though at least it shows a tiny thing that makes it a bit less generic than Twin Hawk. At the start of every level there are a bunch of soldiers who are doing funny background events. And yeah, that's it.

This would've been a great game if it wasn't so horribly balanced. Got the red item fully powered up? Spam the button and everything goes away effortlessly. Get clipped more than halfway through the game? Prepare to continue feed. It would be fine if you simply lost your power ups upon death, but Fire Shark commits the sin of having to up your speed gradius style. Did I mention these power ups actively avoid you and bounce towards the top of the screen to assure you'll probably die trying to snag it?

Most of these issues weren't a big deal in stages 1 to 5, but beyond that, its pretty much impossible to play the game properly if you die at all. I'm not sure how anyone would do it without simply bomb spamming from checkpoint to checkpoint.

Definitely won't be playing again after beating it on this games idea of "normal". There are just far too many other great games on the console.

Most of these issues weren't a big deal in stages 1 to 5, but beyond that, its pretty much impossible to play the game properly if you die at all. I'm not sure how anyone would do it without simply bomb spamming from checkpoint to checkpoint.

Definitely won't be playing again after beating it on this games idea of "normal". There are just far too many other great games on the console.

Very solid, I think it might be Toaplan's best shooter on Genesis, and the usual quirks innate to this team's work are more lighthearted and endearing this time around. Little flourishes like planes that fail their takeoffs and enemy soldiers running out of their tanks after they blow up, cute stuff.

Nunca pensei que ia dar uma nota tão baixa para um jogo da Toaplan, mas né, aqui estamos...

O jogo na verdade não é ruim nem nada. É um shmup bem tradicional, baseado em 1942 da Capcom, com poucos powerups para te confundir (basicamente speed, power que evolui de 3 em 3 coletados, e 3 tiros de cores diferentes) e 10 estágios antes de reiniciar o loop. Pouca variação de inimigos e poucos padrões dentro desses poucos inimigos. Padrão.

O problema é mais na execução do que no conceito em si. Ainda mais quando o maior causador de mortes do jogo é o fato dos powerups de tiro ficarem por longos segundos (eu chuto cerca de 30 segundos) na tela, te fazendo desviar deles com mais cuidado que tu desvia dos proprios tiros inimigos, e a consequência disso é que tu acaba morrendo de bobeira por causa disso. Principalmente pelo fato de que o powerup vermelho é claramente o mais forte, quase trivializando o jogo em alguns momentos. Esse problema de game design fica bem evidente nos estágios finais, onde tu tem um absurdo de 3 a 4 powerups de uma mesma cor na tela te fazendo desviar enquanto já está desviando dos inimigos em um numero bem relevante.

Fora isso, Fire Shark não tem nada que realmente chame a atenção visualmente. As músicas também não são nada de mais. Vindo da Toaplan, isso é decepcionante.

Não é ruim, porem, também não é bom. As vezes, era o que a gente tinha em mãos nos anos 90.

O jogo na verdade não é ruim nem nada. É um shmup bem tradicional, baseado em 1942 da Capcom, com poucos powerups para te confundir (basicamente speed, power que evolui de 3 em 3 coletados, e 3 tiros de cores diferentes) e 10 estágios antes de reiniciar o loop. Pouca variação de inimigos e poucos padrões dentro desses poucos inimigos. Padrão.

O problema é mais na execução do que no conceito em si. Ainda mais quando o maior causador de mortes do jogo é o fato dos powerups de tiro ficarem por longos segundos (eu chuto cerca de 30 segundos) na tela, te fazendo desviar deles com mais cuidado que tu desvia dos proprios tiros inimigos, e a consequência disso é que tu acaba morrendo de bobeira por causa disso. Principalmente pelo fato de que o powerup vermelho é claramente o mais forte, quase trivializando o jogo em alguns momentos. Esse problema de game design fica bem evidente nos estágios finais, onde tu tem um absurdo de 3 a 4 powerups de uma mesma cor na tela te fazendo desviar enquanto já está desviando dos inimigos em um numero bem relevante.

Fora isso, Fire Shark não tem nada que realmente chame a atenção visualmente. As músicas também não são nada de mais. Vindo da Toaplan, isso é decepcionante.

Não é ruim, porem, também não é bom. As vezes, era o que a gente tinha em mãos nos anos 90.

This game is honestly greatly crafted by looking at how they designed each stage to make great use of each of the different power levels of your main shot and how to make smart use of its angles for the most efficient coverage. Too bad you only get to use 1 of 3 cuz green and red power ups are almost useless, this is the first shmup I have played that makes me want to avoid almost all of its power ups (and they probably knew too cuz the worse weapons stay on screen for longer, did they want it to act like non-lethal obstacles?). I want to say the green power up was made as a hidrance the player needs to avoid so it's probably excusable, but all the promo art makes it seem like they wanted you to use the Flameworther but it's so not worth it close to 100% of the time.

The game isn't nearly as brutal as the original JP release but it's a memo game through and through, at least for the first loop. The hitbox of your plane being on its wings instead on the center is one of those "Realistically unfun" mechanics, makes it very desorienting to play after other shmups, but at least it's unique.

The melodies in this game are good but the sound chip make it sound super bad on the original machine (on the Mega Drive it sounds better at least). The presentation for 1989 it's pretty good for what it's worth, very chunky sprites, but it's a bit same-y on the eyes, and the bullets have some severe visibility problems in some stages.

I probably won't chase for the 1-All, not in the foreseeable future at least. It's a cool game that's weighted down by some weird choices (I don't wanna say they are necessarily bad). Hostile power ups may probably be the most interesting mechanic I have seen from a game of this era, but to me it's completely annoying.

Give it a go, see if it is for you.

The game isn't nearly as brutal as the original JP release but it's a memo game through and through, at least for the first loop. The hitbox of your plane being on its wings instead on the center is one of those "Realistically unfun" mechanics, makes it very desorienting to play after other shmups, but at least it's unique.

The melodies in this game are good but the sound chip make it sound super bad on the original machine (on the Mega Drive it sounds better at least). The presentation for 1989 it's pretty good for what it's worth, very chunky sprites, but it's a bit same-y on the eyes, and the bullets have some severe visibility problems in some stages.

I probably won't chase for the 1-All, not in the foreseeable future at least. It's a cool game that's weighted down by some weird choices (I don't wanna say they are necessarily bad). Hostile power ups may probably be the most interesting mechanic I have seen from a game of this era, but to me it's completely annoying.

Give it a go, see if it is for you.