31 Reviews liked by Baxter

Pokémon Blue Version

1996

This game is such an interesting abstraction of the Japanese cityscape and countryside: I would say it feels most not like a central-Tokyo but like it was designed by someone who lived in one of the major cities an hour or two from central Tokyo. You get the occasional dense area with a skyscraper or two (Saffron City), dense collections of single family homes (Celadon City), but there's still the countryside running through mountains and forests, farming towns here and there.

That is easily Pokemon Blue's most interesting trait: it's a world based on reality, but not in the direction of an Earthbound that's more focused on constantly parodying America or people. Pokemon Blue is a game more interested in the idea of adding a layer of mystery (world of pokemon) and exaggeration (everyone catches pokemon!) to the mundane normal everyday life. I imagine this (and the affordances of the Game Boy and the 151 pokemon, and the marketing efforts of Nintendo) is what helped to capture the minds of the initial millions of players! I'm not sure how much of that exists today, where the series feels a bit more phoned in and calculated.

It's honestly quite disturbing the extent that Satoshi Tajiri's artistic idea become full-on media-mix/anime-ified - most symbolic of this is how sprites underwent slight revisions between the original JP red/green to US red/blue to yellow to bring things 'more in line with the anime' - a direction which, I think, informs the series direction today: something that's more interested in doing only what's necessary to keep the brand going, rather than an interest in the kind of design fundamentals Tajiri/team had that allowed them to conceive of Pokemon Blue in the first place.

The story in Blue is most interestingly not at all much of an anime story. Nobody is really fleshed out except potentially Giovanni, the game feels like a series of vignettes where the sport-like Pokemon battling at times briefly overlaps with the reality of our world. Lt. Surge fought with pokemon in a war, Mew is from South America, the moon landing happened in 1969, people are addicted to gambling, there's a crime syndicate, pokemon can die and become ghosts. There's a lot of room for your imagination to think about.

I loved the underground walkways that feel like the long, underground train station walkways in Japan, or even arguably underground shoutengai (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sh%C5%8Dtengai). How the Celadon "Mansion" is a mistranslation of the Japanese Manshon (often a 5-10 story apartment or mixed use building), how it has the Game Freak devs. The department store inspired by big Japan department stores.

I think the first 2/3 of this game (through Silph Tower) is really well paced, I love how you go between countryside exploration and weird little dungeons in urban settings or caves. The last 1/3 of the game feels a bit more out of place - the 'science' angle, while interesting, kind of starts and ends with Cinnabar island. Seafoam Island and Victory Road are fine, but they feel less connected to the whole game's sense of place compared to e.g. the rocket base or mt. moon. I don't think this detracts from the strength of the game, but the game did feel like it was dragging by that point - the fact it began doing block puzzles might be symbolic of that. (Ha ha)

An aside: The core of the "trainers are multiple pokemon, random encounters are one pokemon" is a brilliant design choice - they can express trainer personality through this, they can characterize spaces like dungeons or caves based on who is there. I actually wanted to see more of the Viridian Forest-type dungeon - where not everything is a random encounter tile.

--

After playing, it does feel like the game is at a bit of a crossroads. I think Tajiri definitely had more he wanted to do with his vision, but they may not have been in-line with the more obvious routes to 'improving' the game.

The more obvious routes, to me, neither of which interest me personally, are:

- Increasing the traditional storytelling: clear villain characters, more cutscenes, more regularly paced villain-related levels. This could help attract an audience put off by the way Pokemon Blue feels like falling into a story at times (which I personally prefer, haha). It would also increase franchise tie-in and business synergies!

- Making the battle system 'better' and not a pushover. Make the game more technical, increase training options, create harder battles or challenges - as this would be the only way to 'balance' the game from becoming too easy. This lays a lot of weird traps though, and I think pokemon's devs fell into most of them: stark divides between the 'true combat postgame', many compulsive traps around perfecting stats/builds (rather than letting you teambuild freely), etc.

Personally I would have liked it if the game went harder on the weird influences and level layouts, maybe experimenting with a smaller level range or different methods of training other than bland 'QoL' features to help even leveling... but hey! I'm not the billionaire company here...

That is easily Pokemon Blue's most interesting trait: it's a world based on reality, but not in the direction of an Earthbound that's more focused on constantly parodying America or people. Pokemon Blue is a game more interested in the idea of adding a layer of mystery (world of pokemon) and exaggeration (everyone catches pokemon!) to the mundane normal everyday life. I imagine this (and the affordances of the Game Boy and the 151 pokemon, and the marketing efforts of Nintendo) is what helped to capture the minds of the initial millions of players! I'm not sure how much of that exists today, where the series feels a bit more phoned in and calculated.

It's honestly quite disturbing the extent that Satoshi Tajiri's artistic idea become full-on media-mix/anime-ified - most symbolic of this is how sprites underwent slight revisions between the original JP red/green to US red/blue to yellow to bring things 'more in line with the anime' - a direction which, I think, informs the series direction today: something that's more interested in doing only what's necessary to keep the brand going, rather than an interest in the kind of design fundamentals Tajiri/team had that allowed them to conceive of Pokemon Blue in the first place.

The story in Blue is most interestingly not at all much of an anime story. Nobody is really fleshed out except potentially Giovanni, the game feels like a series of vignettes where the sport-like Pokemon battling at times briefly overlaps with the reality of our world. Lt. Surge fought with pokemon in a war, Mew is from South America, the moon landing happened in 1969, people are addicted to gambling, there's a crime syndicate, pokemon can die and become ghosts. There's a lot of room for your imagination to think about.

I loved the underground walkways that feel like the long, underground train station walkways in Japan, or even arguably underground shoutengai (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sh%C5%8Dtengai). How the Celadon "Mansion" is a mistranslation of the Japanese Manshon (often a 5-10 story apartment or mixed use building), how it has the Game Freak devs. The department store inspired by big Japan department stores.

I think the first 2/3 of this game (through Silph Tower) is really well paced, I love how you go between countryside exploration and weird little dungeons in urban settings or caves. The last 1/3 of the game feels a bit more out of place - the 'science' angle, while interesting, kind of starts and ends with Cinnabar island. Seafoam Island and Victory Road are fine, but they feel less connected to the whole game's sense of place compared to e.g. the rocket base or mt. moon. I don't think this detracts from the strength of the game, but the game did feel like it was dragging by that point - the fact it began doing block puzzles might be symbolic of that. (Ha ha)

An aside: The core of the "trainers are multiple pokemon, random encounters are one pokemon" is a brilliant design choice - they can express trainer personality through this, they can characterize spaces like dungeons or caves based on who is there. I actually wanted to see more of the Viridian Forest-type dungeon - where not everything is a random encounter tile.

--

After playing, it does feel like the game is at a bit of a crossroads. I think Tajiri definitely had more he wanted to do with his vision, but they may not have been in-line with the more obvious routes to 'improving' the game.

The more obvious routes, to me, neither of which interest me personally, are:

- Increasing the traditional storytelling: clear villain characters, more cutscenes, more regularly paced villain-related levels. This could help attract an audience put off by the way Pokemon Blue feels like falling into a story at times (which I personally prefer, haha). It would also increase franchise tie-in and business synergies!

- Making the battle system 'better' and not a pushover. Make the game more technical, increase training options, create harder battles or challenges - as this would be the only way to 'balance' the game from becoming too easy. This lays a lot of weird traps though, and I think pokemon's devs fell into most of them: stark divides between the 'true combat postgame', many compulsive traps around perfecting stats/builds (rather than letting you teambuild freely), etc.

Personally I would have liked it if the game went harder on the weird influences and level layouts, maybe experimenting with a smaller level range or different methods of training other than bland 'QoL' features to help even leveling... but hey! I'm not the billionaire company here...

THE MAZE...reminded me of yu-no's later amazing 'labyrinth' (in the metaphorical sense)

To give more details... it's a meta take on the mystery/detective genre? Of course by the 80s mystery had likely played with twists around point of view / narrator a lot, I wonder if this was the devs' stab at adapting those ideas to a game format. As an experiment, I'm not sure it entirely works fully - in hindsight you can read Yasu's actions as disobeying you, twisting the truth, but in the moment it feels like the game is just kind of buggy or missing info - even if this feeling is likely intentional. Whereas in a book..you can read the book. You could get 'stuck' in a book but not in the same way you get stuck in a game.

That's not to say that the game is pretty funny at times, playing with the command-input format (different texts playing for repeated interactions, gags, etc). I like that it's very aware of the affordances the commands give - building tension through the labyrinth, Yasu's constant stare in some spots.

I kind of wonder how you were to deduce this yourself. I ended up using a guide halfway through so I wasn't sure if you could ask Yasu about the IOU or diaryy to get hints that he was the culprit... oh well!

Other than the feelings of 'we're never going to figure this out' and the tension of Yasu's always wanting things to be done with I think the main characters don't get quite enough screentime for the payoff/reveals to feel super justified.

But overall hey! Pretty interesting still. And the use of that maze at the end is such a great subtle horror moment. We think of old games as being archaic but really they seem happy to shift registers at will...

To give more details... it's a meta take on the mystery/detective genre? Of course by the 80s mystery had likely played with twists around point of view / narrator a lot, I wonder if this was the devs' stab at adapting those ideas to a game format. As an experiment, I'm not sure it entirely works fully - in hindsight you can read Yasu's actions as disobeying you, twisting the truth, but in the moment it feels like the game is just kind of buggy or missing info - even if this feeling is likely intentional. Whereas in a book..you can read the book. You could get 'stuck' in a book but not in the same way you get stuck in a game.

That's not to say that the game is pretty funny at times, playing with the command-input format (different texts playing for repeated interactions, gags, etc). I like that it's very aware of the affordances the commands give - building tension through the labyrinth, Yasu's constant stare in some spots.

I kind of wonder how you were to deduce this yourself. I ended up using a guide halfway through so I wasn't sure if you could ask Yasu about the IOU or diaryy to get hints that he was the culprit... oh well!

Other than the feelings of 'we're never going to figure this out' and the tension of Yasu's always wanting things to be done with I think the main characters don't get quite enough screentime for the payoff/reveals to feel super justified.

But overall hey! Pretty interesting still. And the use of that maze at the end is such a great subtle horror moment. We think of old games as being archaic but really they seem happy to shift registers at will...

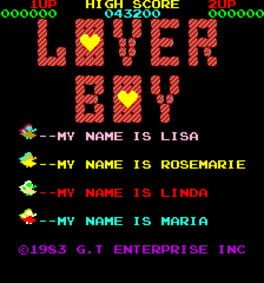

Yakyuuken

1979

I Uncovered the First Eroge Ever and it’s THIS?? (LOST MEDIA!!!) 😱

(Available on Bump Combat with photo accompaniment)

(Also on Gaming Alexandria)

One year ago, after weeks of intensive research, I put together a culmination of available knowledge on dB-Soft’s notorious, under-documented 177. My intent was for this to be the first of many projects detailing the cultural role and history of key eroge works. My research into 177 bore fruit for seemingly countless historical forays into the likes of Lover Boy, Lolita Syndrome, Night Life, and Emmy. Information on these titles was somewhat scant to be sure, but there was enough to construct a narrative. Lover Boy was knocked out in a couple days, and in revisiting my list of potential topics I was intrigued by a title I’d popped on there without much thought:

Yakyūken (Hudson Soft, n.d.)

Supposedly this predated Koei’s Night Life and even On-Line Systems’ Softporn Adventure by quite some margin, though the specific date was up for debate if not entirely lost. If I were to talk about PSK’s Lolita: Yakyūken at some point, surely it would make more sense to tackle its progenitor first. This presented a few problems. First, there is not exactly a plethora of information about this primitive eroge. Second, it seems to have left no impact. Third, there was no way to play it. For all I knew, Yakyūken did not even exist in the first place, and if it had, nobody had bothered to back it up. VGDensetsu had collated some basic information and screenshots,[1] and BEEP had acquired a copy in 2015,[2] but these only served to tease me, increasing my appetite for forbidden fruit. The type-in version printed in MZ-700 Joyful Pack only had one page of the code documented online, and a search of previous Yahoo! Auctions listings for either cassette came up empty. But MZ-700 Joyful Pack seemed to turn up frequently, that seemed the best course of action.

Unwilling to wait for it to be listed on Yahoo! Auctions again, I turned to Kosho, Japan’s secondhand bookstore search engine. Finding one listing, without a picture, I took a gamble on a copy of what appeared to be the right issue of MZ-700 Joyful Pack, and patiently waited. A month later, it arrived at my door, and while it looked different from the one I had seen online, I excitedly opened it up, flipping through each page for my treasure. Were I looking into computerised Shogi, Go, and Mahjong, I would have found it. Every type-in was a trainer, solver, or some other supplementary program for these three Japanese board games. The trail turned ice cold. Distraught, I resigned myself to searching Yahoo! Auctions weekly for the correct MZ-700 Joyful Pack or a Yakyūken cassette. After another month, the same tape I had seen on BEEP popped up; HuPack #2 for Sharp MZ-700.

Forty years old. Dirty. Discoloured. Untested. I set up my bid in a panic, shaking with anticipation for the next four days, pleading nobody would top my already high bid. I won, it reached my proxy after a week, it was on its way. Quaking as a leaf in a stiff wind, it arrived. Quickly it dawned on me my tape deck had been broken for years, but some kind folks at Gaming Alexandria thankfully offered to dump and scan it on my behalf.[3] After many months of searching, this seemingly lost progenitor to the entirety of erotic gaming was available again. Nobody particularly cared, but I had the first piece of the puzzle I needed. Tape back in hand, I imported a copy of Miyamoto Naoya’s seminal Introduction to Cultural Studies: Adult Games, the first edition of Bishōjo Game Maniax, Sansai Books’ 35 Years of Bishōjo Game History, and Maeda Hiroshi’s Our Bishōjo Game Chronicle, the only books I could source that made mention of Yakyūken.

Only problem was, what exactly is Yakyūken. Why are we stripping while playing rock paper scissors in the first place?

On the Origins of Rock Paper Scissors

Though now effectively ubiquitous across a multitude of cultures, rock paper scissors type hand games (ken) have enjoyed an astounding popularity in Japan since the eighteenth century. Brought to Japan from China sometime before 1743, the original form of Japanese ken is referred to today as kazu-ken, Nagasaki-ken, and hon-ken (“original ken”). Players sat opposite one another, showed any number of fingers on their right hand, and called out a guess as to what the sum of the fingers would be. The left hand counted one’s wins, and the loser of a set was made to drink a cup of sake. With its specific hand movements, Chinese mode of calling numbers, and embedded rules of drinking, kazu-ken flourished in the red-light district of Yoshiwara.[4] Its exoticism in the time of sakoku and Japanese Sinophilia no doubt contributed to its proliferation. However, the theatrics and, as Japanologist Sepp Linhart argues, ritualistic rules made the game difficult to penetrate for those not in the know, a far cry from the rock paper scissors we know today.[5]

Subsequent iterations of ken remedied the complications through the familiar sansukumi-ken (“ken of the three which cower one before the other”) format.[6] A wins over B, B over C, C over A. In its first iteration, mushi-ken, the frog (represented by the thumb) defeated the slug (the pinkie) which won over the snake (index finger). Itself another cultural import from China, mushi-ken gradually acquired a reputation as a game explicitly for children[7], but what won over it culturally was kitsune-ken, later Touhachi-ken. The kitsune trumps the head of the village which wins over the hunter which kills the kitsune. This two-handed ken was more popular among adults in and out of districts like Yoshiwara, particularly as the basis for libations or stripping.[8] The accompanying song, dance, and act of playing kitsune-ken as a strip-game were known as chonkina, the loser doffing an article of clothing until one was bare. Clearly intended for adult entertainment, chonkina nonetheless made itself known to children in time, as recalled in Shibuzawa Seika’s Asakusakko:

"Two children, standing opposite to each other, after having put together the palms of their hands right and left as well as alternately, finally make one of the postures of fox, hunter or village headman to decide a winner. The loser has to put off a piece of what he is wearing every time, until one of them is stark naked. To see the little children on cold winter days trembling, because one after another piece of cloth was stripped them off is a strange scene which can no longer be seen today."[9]

As the nation opened to foreigners again, chonkina became well known among foreigners, and due to the bad reputation it was bestowing to Japan, it was outlawed from September 1894 onward.[10]

Children’s mushi-ken would go on to evolve into jan-ken, the rock paper scissors with which we are familiar, but the specifics of when and how are unclear and unimportant for our purposes. Jan-ken was the preeminent ken by the end of the Meiji period, and ken on the whole was relegated to the realm of children. However, as a game intimately familiar to nearly all Japanese beyond childhood, the simple, fast-paced trichotomy of jan-ken, alongside its association with punishment systems like drink and stripping afforded jan-ken staying power beyond childhood.[11] It is a game which effectively boils down to luck, allowing for decision-making that, if nothing else, is understood to be fair.

Putting the Yakyū in Yakyūken

It’s October, 1924 in Takamatsu. To break in the new ground at Yashima, nearby industrial companies and technical schools are holding a baseball tournament. In a crushing defeat of 0-8, the team from Iyo Railway (later Iyotetsu) was humiliated by the Kosho Club, composed of students from Kagawa Prefectural Takamatsu Commercial School (now Kagawa Prefectural Takamatsu Commercial High School). [12] Later that night, the teams held a get-together at a nearby ryokan, putting on enkai-gei (“party tricks”). Manager of the Iyotetsu team and senryū poet, Goken Maeda, devised an arrangement and choreography of the 1878 nagauta piece “Genroku Hanami Odori.” The Iyotetsu team danced to shamisen in their uniforms to the delight of those in attendance. This first iteration of what would become Yakyūken (literally “baseball fist”) was based on the Japanese rock paper scissors variant kitsune-ken, but by 1947 it came to reflect now common variant jan-ken.[13] The Yakyūken performance was repeated at a consolation party in Iyotetsu’s hometown of Matsuyama, quickly gaining popularity therein and throughout Japan as the team performed it while on tour.[14]

The camaraderie instilled in audiences by the Iyotetsu team’s dance, and its spread as enkai-gei, led to many localised instances of this new form of jan-ken being performed.[15] The specifics of how prevalent it became are impossible to discern, but what is known is that Yakyūken, as with the earlier kazu-ken and kitsune-ken, became another diversion used as an excuse to imbibe and to disrobe.

野球するならこういう具合にしやしゃんせ ~ソラ しやしゃんせ~

投げたら こう打って 打ったなら こう受けて

ランナーになったらエッサッサ ~アウト・セーフヨヨイノヨイ~

It’s 1954. Contemporary Ryūkōka artists Ichiro Wakahara and Terukiku of King Records,[16] Yukie Satoshi and Kubo Takakura of Nippon Columbia,[17] and Harumi Aoki of Victor Japan[18] have all released 78 rpm singles with their own takes on Yakyūken. This musical multiple discovery of a still relatively local song brought into question where it had actually originated, with a photograph of the Matsuyama consolation party cementing Goken Maeda as its creator.[19] With this, Maeda’s original, non-chonkina song and dance came to be understood as honke Yakyūken, the orthodox iteration, the way it was meant to be. As the dance spread, alcohol flowed and clothes were shed. In an attempt to preserve the sanctity of Maeda’s phenomenon, fellow poet Tomita Tanuki established an iemoto system for honke Yakyūken around 1966, formalising its lyrical structure and attempting to preserve Yakyūken as a way, not unlike sumo. As iemoto, Tanuki in effect declared himself to be the highest authority on honke Yakyūken — it did not and would not matter how Yakyūken was actually enjoyed colloquially, only what the iemoto approved of constituted the real thing. At the same time, the city of Matsuyama introduced a new taiko performance — the Iyo-no-Matsuyama Tsuzumi Odori — for that year’s Matsuyama Odori festival. While it was popular, it lacked regionalism, and so in 1970, it was replaced with Yakyūken Odori.[20] It wasn’t just local flavour, however, as the year prior Yakyūken became a national phenomenon for more unsavoury reasons.

Birth of a Sensation: Yakyūken Breaks Into the Mainstream, or Tits Out for TV

Just as in the United States, the 1960s in Japan were marked by an increase in individuals’ buying power and the proliferation of television. Whereas the prior decade relegated television sets to the homes of the wealthy or in street-side display windows, by 1970, 90% of Japanese households owned at least one television set.[21] The penetration of the entertainment sphere into the domestic realm led to a berth of variety and comedy shows, all emphasising the joys of laughter. This proliferation rose concerns among cultural critics in the 1960s, with fears that the often lowbrow, thoughtless humour which frequently lampooned violence and sexuality were unsuited to the home, particularly where children might be watching.[22] Furthermore, such programming was becoming increasingly rote and prescriptive in its approach, thereby lessening its effect with each broadcast, making this new mode of entertainment lascivious and boring. In breaking free of an ever rigid mould, Japanese television’s saviour came in the form of Hagimoto Kinichi and Sakagami Jirō’s comedy duo Konto 55-gō. Pronounced as “konto go-jyuu go gō,” the name’s syllabic tempo, evocation of go-go dancing, and abstruse referencing of baseball player Oh Sadaharu’s 55th homerun of the 1964 season all brought about a rapidity and contemporary sensibility fitting of the pair’s comedic stylings.[23]

From their television debut in 1967, Konto 55-gō demonstrated a dynamic physicality in stark contrast to similar acts, often moving so fast that cameras could not keep up with them, the laughter of the audience sometimes being the only indicator of a punchline’s delivery.[24] While a breath of fresh air, cultural critics lambasted this seeming over-correction as yet again inappropriate for home audiences. On the other hand, audiences adored the duo’s comedy, with renowned Buddhist nun, translator of Genji Monogatari into modern Japanese, and self-described Konto 55-gō fan Jakucho Setouchi (then known as Harumi Setouchi) saying Kinichi and Jirō made her “laugh so much that [her] stomach ached."[25]

This focus on unpredictability, shattering of expectations and conventions, and need to perpetually one-up themselves, Konto 55-gō chased and reinforced the proliferation of what Allan Kaprow described as ‘Happening.’ Originally coined in 1959 in reference to art-related events in which the artist took on theatrical directions and modes of expression, Happenings flourished throughout the United States through the 1950s and 1960s, spreading globally but predominantly in Germany and Japan.[26] In the context of the Japanese television industry, ‘Happening’ was co-opted to refer to anything unscripted — quite the opposite from its intent as a label for deliberate performance — after the early 1968 program Kijima Norio Happuningu Sho (“Kijima Norio’s Happening Show”).[27] To be clear, Happenings in this context were still partially staged just as art Happenings were, but the intent from producers was that Happenings would go off the rails by virtue of a lack of scripting and the co-operation and involvement of audience participants. As other shows and producers chased this spontaneity and carried in the wake of Konto 55-gō’s pioneering transgressions, the stakes became higher and content needed to become more compelling, more novel, more edgy, more risque.

The most critical apex of Happening for our purposes came in 1969 on Konto 55-gō no Urabangumi o Buttobase (“Konto 55-gō Blow away the competition”). It was here that Yakyūken was introduced as a segment of the program, with Kinichi and Jirō facing off against numerous women, each stripping an article of clothing upon a loss. Removed articles were then auctioned to raise funds for children orphaned by traffic accidents.[28] The segment was an enormous hit among adults and children, some critics praising this nakedness as incredibly real, the pinnacle of the Happening.[29] At the same time, just as with all of Konto 55-gō’s antics, many loathed this primetime strip tease wholly inappropriate for children to view, some citing it as a siege against one of the sole bulwarks left against Japan’s growing moral decline, the home.[30] Scorn came not only from without, however, but within as well. Kinichi would later go on to say Konto 55-gō no Urabangumi o Buttobase was his most disliked programme he ever worked on, in no small part due to the Yakyūken segment which brought viewers in not for the comedy of the duo, but for the titillation and obscenity of the Yakyūken act itself.[31] Furthermore, in 2005, Kinichi visited Matsuyama to apologise personally to fourth honke Yakyūken iemoto Tsuyoshitoshi Sawada for misrepresenting Yakyūken. Despite this resentment from Kinichi and some critics, Yakyūken reinvigorated jan-ken into a game with stakes, with merriment, with rules everyone was already familiar with, with a catchy song and dance, that brought the Happening into the real world.

Through Konto 55-gō’s work, Yakyūken presented the same problem that chonkina had in the previous century — a breaking of the boundaries between adult entertainment and the recreation of children. This was no longer bound to the district of Asakusa, but the whole of Japan. Further still, the growing popularity of Yakyūken and its association with Konto 55-gō spread the popular conception of the dance originating as a strip performance, rendering the attempts of Tanuki’s iemoto system to preserve the sanctity of Maeda’s original work increasingly ineffective. The iemoto system only had merit when the associated act could be considered a tradition worth preserving such as tea ceremony or calligraphy. With Yakyūken compromising the cultural zeitgeist as a strip game, it became difficult to consider it a valuable cultural commodity. While it is possible this was the greater underlying reason for Matsuyama’s introduction of Yakyūken Odori to the Matsuyama Odori festival in 1970, it cannot be stated as certainty. What was certain was that Yakyūken was here to stay as a television staple, at least for a moment.

Yakyūken remained a part of Konto 55-gō no Urabangumi o Buttobase through to the end of 1969, afterwards being spun-off into its own program Konto 55-gō no Yakyūken!! From November 26, 1969, thirty minutes of strip rock-paper-scissors littered the airwaves every Wednesday at 9PM until the program was discontinued in April 1970.[32] Yakyūken would not be broadcast on Nippon TV for another two decades, returning on New Year’s Eve, 1993 as part of Supa Denpa Bazaru Toshikoshi Janbo Dosokai (“Super Radio Bazaar New Year’s Jumbo Alumni Reunion”). Though no longer televised in the interim, Yakyūken remained in the cultural zeitgeist as a strip game. While impossible to discern at what point Yakyūken became a mainstay of Japanese pornographic production, it has become ubiquitous — a cursory search of Japanese pornographic clip site eroterest.net gives over 34,000 results for Yakyūken. What is certain is that Yakyūken similarly became not just a mainstay of Japanese erotic video games, but the foundation of the entire industry.

In Which I Finally Tell You About the Video Game Yakyūken by Hudson Soft

With 500,000 yen in starting capital, brothers Yūji and Hiroshi Kudō founded Hudson Co., Ltd. in Toyohira-ku, Sapporo on May 18, 1973. Named after the duo’s favourite class of train, the 4-6-4 Hudson, Yūji and Hiroshi sold fine art photographs of locomotives. In September, the brothers opened a dedicated amateur radio shop, CQ Hudson, which stood at 3-7-26, Hiragishi, Toyohira-ku into the new millennium.[33] After travelling to the US shortly thereafter to market their wares, Yūji saw personal computers on general sale for the first time, inspiring him to bring home a PolyMorphic Systems Poly-88 to Japan and learn to program, taking on two million yen in credit card debt to finance the purchase.[34] Well before the personal computer revolution hit Japan, The Kudō brothers were pioneers. The shops of Akihabara bore no fruit for them, necessitating the Poly-88 import. By 1975, the Kudōs had fully branched out into personal computer products, turning type-in programs into pre-packaged cassette tape releases for the sake of convenience, and becoming early adopters of NEC’s 1976 TK-80 and Sharp’s MZ-80 line of computers.[35] The Kudō brothers also began to start writing their own programs around this time under the development team name Miso Ramen Group.

Hudson released at least thirty-seven games for the MZ-80 line, available occasionally as type-ins in magazines like Micom or in books like MZ-80B活用研究. There was a little bit of everything in Miso Ramen Group’s offerings, from the Maze War-esque Ramen Maze 3D to Othello to Operation Escape, wherein the player had to sneak out of class not unlike Konami’s 1984 Beatles-laden Mikie.[36] In the summer of 1979, Hudson was approached by a computer manufacturer with a proposal to sell their software by mail order with an advertisement in Micom for July 1979.[37] The ads were a success, with the Kudōs recounting later that deposits at the bank took upwards of thirty minutes because tellers thought they might be criminals.[38] Yakyūken’s existence in this initial advertisement makes it plain that the game was developed prior to mid-1979, and the ad was laid bare in a 1996 television documentary special by NHK. Yet Yakyūken’s status as the first commercial erotic game seems to have fallen to the wayside.

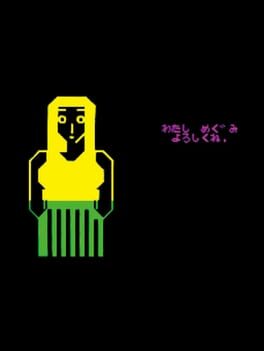

The game is incredibly simple, as one might expect from a preliminary type-in program from the late 1970s.[39] The player decides how many articles of clothing they wish themselves to have, not dissimilar from a lives system, and is then introduced to their opponent, Megumi.

わたしめぐみよろしくね。(“I’m Megumi, nice to meet you.”)

A few bars of the Yakyūken song beep languidly from the piezoelectric speaker with a bold OUT!! SAFE!! ヨヨイノヨイ covering the screen. The player chooses グ (rock), チョキ (scissors), or パ (paper). In the event of a tie, the process repeats. Should the player lose, an article of clothing is theoretically removed with no visual indication. Should they win, Megumi is declared ‘out’ and her avatar removes an article of clothing. Shirt, skirt, bra, panties. An eyebrow is cocked when her outer attire comes off, the other joining in twain when her bra comes loose. When she loses her panties, Megumi covers her crotch and shrieks "キャー!!はやくあっちへいって!!" (“Kyaa! Quickly, get out!!”) Game end. The original MZ-80 release was monochromatic, but the later MZ-700 versions were in colour, used to minimal effect. It really is as simple as that.

Who’s on first?

Koei’s first entry in their Strawberry Porno series, Night Life, dominates much of the historical record as the earliest erotic game, particularly in the West. Hardcore Gaming 101, Matthew T. Jones, Wikipedia, and MobyGames (among others) authoritatively claim it to be the first, and on occasion one might see PSK’s Lolita Yakyūken cited in its place, but both works released in 1982, the same year as Custer’s Revenge.[40] ASCII Corporation’s history of the NEC PC-8801 show similar family trees wherein Night Life is the root of all Japanese eroge, its own ancestor being On-Line Systems’ 1981 Softporn Adventure.[41] So too does Pasokon Super Special PC Game 80s Chronicle.[42] When Yakyūken is mentioned by these sources, it is as a possibility, something which might be true but lacks veracity, yet the evidence is plain.

Perhaps Yakyūken was simply too early, releasing before heavy-hitter platforms like the NEC PC-88 or Fujitsu FM-7. The MZ-80 line’s flagship was the MZ-80K, released in 1978. It was available only as an assembly kit, which, coupled with its high retail price of ¥198,000, left it in the realm of the enthusiast and academic (particularly engineering students).[43] While games were blatantly possible on the platform, they were far from the focus, limiting the audience for Hudson’s games, particularly Yakyūken, dramatically. Further still, it was sold primarily through mail order, advertised in niche magazines without pictures. Hudson got paid, and quite well at that, but orders came for a litany of their products. Without knowing this was an explicit game, the prospect of playing digital jan-ken must have paled in comparison to Othello or Hudson’s more arcade-style offerings. By the time it came to the next generation on 1982’s MZ-700, the floodgates had already been opened, and platforms capable of graphics dominated the eroge space.

Perhaps Night Life and Lolita Yakyūken take the historiographical spotlight because they lack the primitiveness of Yakyūken. There is no denying that Yakyūken lacks the graphical fidelity of its descendants. Bound by the 80 column by 50 row display of the MZ-80K, space is limited, colour an impossibility, and everything is comprised of text characters as the hardware could not display graphics. The Japanese character ROM bears no curvilinear shapes apart from circles.[44] The hand signs are malformed, and though your opponent, doesn’t look bad per se, her rectangular body’s attempt at an hourglass figure is not exactly stunning. As games writer Yoshiki Osawa described it in the 2000 book Bisyoujyo Game Maniax, [sic] the visuals lack gender specificity, and exhibit a crudeness that cannot even be called ASCII art.[45] Compared to the full colour illustrations of PSK’s Lolita Yakyūken or even the silhouettes of Night Life, Yakyūken comes up short.

Perhaps Yakyūken was too outdated to catch on without some additional gimmick such as lolicon artwork. The original dance craze had occurred a quarter-century earlier, and it had been barred from television for nearly a decade. By the admission of MZ-700 Joyful Pack, Yakyūken was unlikely to resonate with those who did not grow up in the postwar period. A craze to be sure, but a craze for a generation past, one which had little interest in computing. The type-in’s accompanying text even had to make explicit that Yakyūken had virtually nothing to do with baseball, despite its name, as well as the fact this was a game of chonkina.

What these comparisons ignore is that stunning the world was not necessarily Yakyūken’s purpose. Though sold commercially, projects in its vein from Hudson were as much at home on cassette as they were printed as type-ins. By having their code laid entirely bare, type-ins meant hobbyists dabbling in a brand new technology could visually see and alter the program. The type-in’s purpose was to demonstrate what a computer could do. A user could change Megumi-chan into a man, increase her bust size, style her hair. Perhaps they could do away with jan-ken and replace its symbols with those from Touhachi-ken. Why not increase the number of options available for some digital Rock Paper Scissors Lizard Spock? Just as type-ins are used to teach today, so were they then — deliberately open ecosystems in which to learn. Night Life and Lolita Yakyūken were as walled gardens, the magic unable to be discerned.

In Which I Admit This is All Pedantry and Ultimately Does Not Matter

The fact of the matter is that this is all pedantry and ultimately it does not matter. While monumental firsts are readily recorded, the more niche the subject matter, the more abstruse the truth of a first becomes. Any history student can tell you this after a course on historiography and the historical method. The fact of the matter is that what comes first is arbitrary, determined by fallible, biased humans trying to further an argument.

The search for historical firsts has overtaken much of contemporary historical scholarship, and the problem with this is that there is invariably always an earlier example, and the argument of something as coming earlier is increasingly valueless. Certainly there will always come a true first, but how can we know it is certain with an always imperfect historical record? Does it matter if something came first if it was too ahead of its time? Would we be better off as historians focusing more on moments of critical mass as others in adjacent fields do, such as Marek Zvelebil did in his research on agricultural innovations in the archaeological record?[46] Who is to say. What I can say for sure is that I sincerely hope Yakyūken is not the first commercial erotic game. I hope to be disproved at some point in the future. I hope that in trying to set the record straight in this one instance, it can be set straight in another. I hope the drive for better histories never ends, and that at some point we can dwell less on firsts, and more on more critical narratives in games history, cultural history, human history.

__________________________

[1] Video Games Densetsu, “Yakyūken / 野球拳, Probably the First Erotic Video Game Ever Released.,” Tumblr, November 18, 2016, https://videogamesdensetsu.tumblr.com/post/153336334460/yaky%C5%ABken-%E9%87%8E%E7%90%83%E6%8B%B3-probably-the-first-erotic-video.

[2] “【宅配買取】MZ-700用野球拳(ハドソン)を宮城県仙台市のお客様よりお譲りいただきました|BEEP,” BEEP, April 16, 2019, http://www.beep-shop.com/blog/5921/.

[3] “Hudson Soft - HuPack #2 (Featuring Rowdy-Ball and Yakyūken)(Scans + GameRip) : Hudson Soft,” Internet Archive, July 1, 2023, https://archive.org/details/Hudson-soft-hupack-2.

[4] Sepp Linhart, From Kendô to Jan-Ken: The Deterioration of a Game from Exoticism into Ordinariness (SUNY Press, 1998), 322-323.

[5] Sepp Linhart, “Rituality in the Ken Game,” Ceremony and Ritual in Japan, (2013): 39. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203429549-10.

[6] Linhart, “Rituality in the Ken Game,” 39.

[7] Kitamura Nobuyo. 1933. Kiyu shoran. 2 vols. Tokyo: Seikokan shoten, quoted in Linhart, From Kendô to Jan-Ken, 325.

[8] Stewart Culin, Korean Games with Notes on the Corresponding Games of China and Japan (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1895), 46-47.

[9] Shibuzawa Seika. 1966. Asakusakko. Tokyo: Zoukeisha, quoted in Linhart, From Kendô to Jan-Ken, 334-335.

[10] Hironori Takahashi, “Japanese fist games” (in Japanese): Osaka University of Commerce Amusement Industry Research Institute (2014): 203.

[11] Thomas Crump, Japanese Numbers Game (London: Routledge, 1992). 146.

[12] “本当は脱がない「野球拳」 松山発祥、90年の歴史,” 日本経済新聞, June 29, 2014, https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXNASFG230DO_V20C14A6BC8000/. Accounts seem to differ on the final score, with some sources claiming it was a 0-6 defeat, others 0-8. As 0-8 is cited by the fourth Iemoto of Yakyūken, that is the number I have decided to use.

[13] Takakashi, “Japanese fist games,” 204-205.

[14] Takakashi, “Japanese fist games,” 204-205.

[15] Takao Ohashi, “A Trademark Registration for ‘野球拳おどり’ (Yakyu-Ken Dance ) - パークス法律事務所,” パークス法律事務所 -, December 9, 2021, https://pax.law/topics/blog/1242/.

[16] 野球けん 若原一郎・照菊, YouTube (YouTube, 2023), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H58uhkoQrbo.

[17] 久保幸江・高倉敏 野球拳, YouTube (YouTube, 2015), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Xdfh4dBWeM.

[18] 靑木 はるみ ♪野球けん♪ 1954年 78rpm Record. Columbia Model No G ー 241 Phonograph, YouTube (YouTube, 2022), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ycCAK69hc7w.

[19] “本家 野球拳,” GMOとくとくBB|運営実績20年以上のおトクなプロバイダー, accessed October 2, 2023, http://shikoku.me/iyo-matsuri/raijin/honkeyakyuuken/history/index.html.

[20] “松山野球拳おどりのあゆみ,” 松山野球拳おどり 公式ホームページ, accessed October 2, 2023, https://baseball-dance.com/about/story/.

[21] David Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday: Konto 55-gō and the Teleivision Comedy of the Late 60s” Japan Studies Association Journal 15, no. 1 (2017): 24.

[22] Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday,” 24.

[23] Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday,” 28.

[24] Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday,” 28-30.

[25] Harumi Setouchi, “Tondari hanetari… Konto 55-gō no gei to sugao,” Oh! (August 1968): 176-177, quoted in Humphrey: “Shattering the Everyday,” 30.

[26] Allan Kaprow, “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock (1958),” in Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 1-9.

[27] Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday,” 32.

[28] “欽ちゃん「もっとも嫌いな番組だった」 2人の芸風の違いが浮き彫りになった「裏番組をぶっとばせ!」,” イザ!, September 4, 2018, https://www.iza.ne.jp/article/20180904-HGNF6BYZ5VLH5CV54ZLQFEC2MA/.

[29] Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday,” 36-37.

[30] Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday,” 37.

[31] イザ!, “欽ちゃん”

[32] マスコミ市民 : ジャーナリストと市民を結ぶ情報誌 (36)

[33] “Company Information,” Hudson Soft, December 11, 2000, Internet Archive, https://web.archive.org/web/20001211040400/http://www.hudson.co.jp:80/coinfo/history.html; Brian Eddy, “Video Game History 101: Hudson Soft,” New Retro Wave, January 30, 2017, https://newretrowave.com/2017/01/30/video-game-history-101-hudson-soft/.

[34] Damien McFerran, “Hudson Profile — Part 1,” Retro Gamer Magazine 66, (2009): 68; スペシャル 新・電子立国 第4回 「ビデオゲーム」 ~巨富の攻防~ (NHK, 1996), streaming video, 40:16, Internet Archive. There are conflicting accounts on why Yūji went to the United States and what his first computer was. The information cited here comes from an interview with Yūji himself. Doug Carlston claims that his first computer was actually a SBC80, followed by an IMSAI, but I have not found further evidence to support this claim. See Doug Carlston, Software People: Inside the Computer Business (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985), 253-257.

[35] The specifics of the timeline become unclear around this time; Japanese microcomputers weren’t commercially available for consumers until mid-1976, yet Hudson’s own company history has them pegged as making PC cassettes and equipment in September 1975.

[36] スペシャル 新・電子立国 第4回, 45:10; “エスケープ大作戦 ,” Animaka.sakura.ne.jp, accessed October 2, 2023, http://animaka.sakura.ne.jp/MZ2000/escape_daisakusen.html; Naoki Miyamoto, Erogē Bunka Kenkyū Gairon (Tōkyō: Sōgō Kagaku Shuppan, 2017), 18-19.

[37] マイコン, July 1979, 11.

[38] スペシャル 新・電子立国 第4回, 45:41.

[39] A full playthrough of the MZ-700 HuPack #2 version is available here: https://youtu.be/M6Emyk5_-jY

[40] “Eroge / Hentai Games,” MobyGames, accessed October 2, 2023, https://www.mobygames.com/group/2508/eroge-hentai-games/; “Eroge,” Wikipedia, September 27, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eroge; Matthew T. Jones, “The Impact of Telepresence on Cultural Transmission through Bishoujo Games,” PsychNology Journal 3 (2005): 295; “Retro Japanese Computers: Gaming’s Final Frontier,” Hardcore Gaming 101, accessed October 2, 2023, http://www.hardcoregaming101.net/JPNcomputers/Japanesecomputers2.htm.

[41] 蘇るPC-8801伝説 永久保存版 (Tōkyō: ASCII, 2006), 212.

[42] Mesgamer, “日本最古のエ□ゲー!ハドソンの野球拳を語るの!,” 顔面ソニーレイなの!, accessed October 2, 2023, https://mesgamer.hatenablog.com/entry/2022/02/21/173437.

[43] Sharp, Sharp 100-Year History, (2012), 6-08.

[44] “80k Download - Roms,” MZ, accessed October 2, 2023, https://original.sharpmz.org/mz-80k/dldrom.htm.

[45] 美少女ゲームマニアックス (Tōkyō: Kirutaimukomyunikēshon, 2001), 66.

[46] See Marek Zvelebil, “Transition to Farming in Norther Europe: A Hunter-Gatherer Perspective,” Norwegian Archaeological Review 17 (1984), 104-127.

(Available on Bump Combat with photo accompaniment)

(Also on Gaming Alexandria)

One year ago, after weeks of intensive research, I put together a culmination of available knowledge on dB-Soft’s notorious, under-documented 177. My intent was for this to be the first of many projects detailing the cultural role and history of key eroge works. My research into 177 bore fruit for seemingly countless historical forays into the likes of Lover Boy, Lolita Syndrome, Night Life, and Emmy. Information on these titles was somewhat scant to be sure, but there was enough to construct a narrative. Lover Boy was knocked out in a couple days, and in revisiting my list of potential topics I was intrigued by a title I’d popped on there without much thought:

Yakyūken (Hudson Soft, n.d.)

Supposedly this predated Koei’s Night Life and even On-Line Systems’ Softporn Adventure by quite some margin, though the specific date was up for debate if not entirely lost. If I were to talk about PSK’s Lolita: Yakyūken at some point, surely it would make more sense to tackle its progenitor first. This presented a few problems. First, there is not exactly a plethora of information about this primitive eroge. Second, it seems to have left no impact. Third, there was no way to play it. For all I knew, Yakyūken did not even exist in the first place, and if it had, nobody had bothered to back it up. VGDensetsu had collated some basic information and screenshots,[1] and BEEP had acquired a copy in 2015,[2] but these only served to tease me, increasing my appetite for forbidden fruit. The type-in version printed in MZ-700 Joyful Pack only had one page of the code documented online, and a search of previous Yahoo! Auctions listings for either cassette came up empty. But MZ-700 Joyful Pack seemed to turn up frequently, that seemed the best course of action.

Unwilling to wait for it to be listed on Yahoo! Auctions again, I turned to Kosho, Japan’s secondhand bookstore search engine. Finding one listing, without a picture, I took a gamble on a copy of what appeared to be the right issue of MZ-700 Joyful Pack, and patiently waited. A month later, it arrived at my door, and while it looked different from the one I had seen online, I excitedly opened it up, flipping through each page for my treasure. Were I looking into computerised Shogi, Go, and Mahjong, I would have found it. Every type-in was a trainer, solver, or some other supplementary program for these three Japanese board games. The trail turned ice cold. Distraught, I resigned myself to searching Yahoo! Auctions weekly for the correct MZ-700 Joyful Pack or a Yakyūken cassette. After another month, the same tape I had seen on BEEP popped up; HuPack #2 for Sharp MZ-700.

Forty years old. Dirty. Discoloured. Untested. I set up my bid in a panic, shaking with anticipation for the next four days, pleading nobody would top my already high bid. I won, it reached my proxy after a week, it was on its way. Quaking as a leaf in a stiff wind, it arrived. Quickly it dawned on me my tape deck had been broken for years, but some kind folks at Gaming Alexandria thankfully offered to dump and scan it on my behalf.[3] After many months of searching, this seemingly lost progenitor to the entirety of erotic gaming was available again. Nobody particularly cared, but I had the first piece of the puzzle I needed. Tape back in hand, I imported a copy of Miyamoto Naoya’s seminal Introduction to Cultural Studies: Adult Games, the first edition of Bishōjo Game Maniax, Sansai Books’ 35 Years of Bishōjo Game History, and Maeda Hiroshi’s Our Bishōjo Game Chronicle, the only books I could source that made mention of Yakyūken.

Only problem was, what exactly is Yakyūken. Why are we stripping while playing rock paper scissors in the first place?

On the Origins of Rock Paper Scissors

Though now effectively ubiquitous across a multitude of cultures, rock paper scissors type hand games (ken) have enjoyed an astounding popularity in Japan since the eighteenth century. Brought to Japan from China sometime before 1743, the original form of Japanese ken is referred to today as kazu-ken, Nagasaki-ken, and hon-ken (“original ken”). Players sat opposite one another, showed any number of fingers on their right hand, and called out a guess as to what the sum of the fingers would be. The left hand counted one’s wins, and the loser of a set was made to drink a cup of sake. With its specific hand movements, Chinese mode of calling numbers, and embedded rules of drinking, kazu-ken flourished in the red-light district of Yoshiwara.[4] Its exoticism in the time of sakoku and Japanese Sinophilia no doubt contributed to its proliferation. However, the theatrics and, as Japanologist Sepp Linhart argues, ritualistic rules made the game difficult to penetrate for those not in the know, a far cry from the rock paper scissors we know today.[5]

Subsequent iterations of ken remedied the complications through the familiar sansukumi-ken (“ken of the three which cower one before the other”) format.[6] A wins over B, B over C, C over A. In its first iteration, mushi-ken, the frog (represented by the thumb) defeated the slug (the pinkie) which won over the snake (index finger). Itself another cultural import from China, mushi-ken gradually acquired a reputation as a game explicitly for children[7], but what won over it culturally was kitsune-ken, later Touhachi-ken. The kitsune trumps the head of the village which wins over the hunter which kills the kitsune. This two-handed ken was more popular among adults in and out of districts like Yoshiwara, particularly as the basis for libations or stripping.[8] The accompanying song, dance, and act of playing kitsune-ken as a strip-game were known as chonkina, the loser doffing an article of clothing until one was bare. Clearly intended for adult entertainment, chonkina nonetheless made itself known to children in time, as recalled in Shibuzawa Seika’s Asakusakko:

"Two children, standing opposite to each other, after having put together the palms of their hands right and left as well as alternately, finally make one of the postures of fox, hunter or village headman to decide a winner. The loser has to put off a piece of what he is wearing every time, until one of them is stark naked. To see the little children on cold winter days trembling, because one after another piece of cloth was stripped them off is a strange scene which can no longer be seen today."[9]

As the nation opened to foreigners again, chonkina became well known among foreigners, and due to the bad reputation it was bestowing to Japan, it was outlawed from September 1894 onward.[10]

Children’s mushi-ken would go on to evolve into jan-ken, the rock paper scissors with which we are familiar, but the specifics of when and how are unclear and unimportant for our purposes. Jan-ken was the preeminent ken by the end of the Meiji period, and ken on the whole was relegated to the realm of children. However, as a game intimately familiar to nearly all Japanese beyond childhood, the simple, fast-paced trichotomy of jan-ken, alongside its association with punishment systems like drink and stripping afforded jan-ken staying power beyond childhood.[11] It is a game which effectively boils down to luck, allowing for decision-making that, if nothing else, is understood to be fair.

Putting the Yakyū in Yakyūken

It’s October, 1924 in Takamatsu. To break in the new ground at Yashima, nearby industrial companies and technical schools are holding a baseball tournament. In a crushing defeat of 0-8, the team from Iyo Railway (later Iyotetsu) was humiliated by the Kosho Club, composed of students from Kagawa Prefectural Takamatsu Commercial School (now Kagawa Prefectural Takamatsu Commercial High School). [12] Later that night, the teams held a get-together at a nearby ryokan, putting on enkai-gei (“party tricks”). Manager of the Iyotetsu team and senryū poet, Goken Maeda, devised an arrangement and choreography of the 1878 nagauta piece “Genroku Hanami Odori.” The Iyotetsu team danced to shamisen in their uniforms to the delight of those in attendance. This first iteration of what would become Yakyūken (literally “baseball fist”) was based on the Japanese rock paper scissors variant kitsune-ken, but by 1947 it came to reflect now common variant jan-ken.[13] The Yakyūken performance was repeated at a consolation party in Iyotetsu’s hometown of Matsuyama, quickly gaining popularity therein and throughout Japan as the team performed it while on tour.[14]

The camaraderie instilled in audiences by the Iyotetsu team’s dance, and its spread as enkai-gei, led to many localised instances of this new form of jan-ken being performed.[15] The specifics of how prevalent it became are impossible to discern, but what is known is that Yakyūken, as with the earlier kazu-ken and kitsune-ken, became another diversion used as an excuse to imbibe and to disrobe.

野球するならこういう具合にしやしゃんせ ~ソラ しやしゃんせ~

投げたら こう打って 打ったなら こう受けて

ランナーになったらエッサッサ ~アウト・セーフヨヨイノヨイ~

It’s 1954. Contemporary Ryūkōka artists Ichiro Wakahara and Terukiku of King Records,[16] Yukie Satoshi and Kubo Takakura of Nippon Columbia,[17] and Harumi Aoki of Victor Japan[18] have all released 78 rpm singles with their own takes on Yakyūken. This musical multiple discovery of a still relatively local song brought into question where it had actually originated, with a photograph of the Matsuyama consolation party cementing Goken Maeda as its creator.[19] With this, Maeda’s original, non-chonkina song and dance came to be understood as honke Yakyūken, the orthodox iteration, the way it was meant to be. As the dance spread, alcohol flowed and clothes were shed. In an attempt to preserve the sanctity of Maeda’s phenomenon, fellow poet Tomita Tanuki established an iemoto system for honke Yakyūken around 1966, formalising its lyrical structure and attempting to preserve Yakyūken as a way, not unlike sumo. As iemoto, Tanuki in effect declared himself to be the highest authority on honke Yakyūken — it did not and would not matter how Yakyūken was actually enjoyed colloquially, only what the iemoto approved of constituted the real thing. At the same time, the city of Matsuyama introduced a new taiko performance — the Iyo-no-Matsuyama Tsuzumi Odori — for that year’s Matsuyama Odori festival. While it was popular, it lacked regionalism, and so in 1970, it was replaced with Yakyūken Odori.[20] It wasn’t just local flavour, however, as the year prior Yakyūken became a national phenomenon for more unsavoury reasons.

Birth of a Sensation: Yakyūken Breaks Into the Mainstream, or Tits Out for TV

Just as in the United States, the 1960s in Japan were marked by an increase in individuals’ buying power and the proliferation of television. Whereas the prior decade relegated television sets to the homes of the wealthy or in street-side display windows, by 1970, 90% of Japanese households owned at least one television set.[21] The penetration of the entertainment sphere into the domestic realm led to a berth of variety and comedy shows, all emphasising the joys of laughter. This proliferation rose concerns among cultural critics in the 1960s, with fears that the often lowbrow, thoughtless humour which frequently lampooned violence and sexuality were unsuited to the home, particularly where children might be watching.[22] Furthermore, such programming was becoming increasingly rote and prescriptive in its approach, thereby lessening its effect with each broadcast, making this new mode of entertainment lascivious and boring. In breaking free of an ever rigid mould, Japanese television’s saviour came in the form of Hagimoto Kinichi and Sakagami Jirō’s comedy duo Konto 55-gō. Pronounced as “konto go-jyuu go gō,” the name’s syllabic tempo, evocation of go-go dancing, and abstruse referencing of baseball player Oh Sadaharu’s 55th homerun of the 1964 season all brought about a rapidity and contemporary sensibility fitting of the pair’s comedic stylings.[23]

From their television debut in 1967, Konto 55-gō demonstrated a dynamic physicality in stark contrast to similar acts, often moving so fast that cameras could not keep up with them, the laughter of the audience sometimes being the only indicator of a punchline’s delivery.[24] While a breath of fresh air, cultural critics lambasted this seeming over-correction as yet again inappropriate for home audiences. On the other hand, audiences adored the duo’s comedy, with renowned Buddhist nun, translator of Genji Monogatari into modern Japanese, and self-described Konto 55-gō fan Jakucho Setouchi (then known as Harumi Setouchi) saying Kinichi and Jirō made her “laugh so much that [her] stomach ached."[25]

This focus on unpredictability, shattering of expectations and conventions, and need to perpetually one-up themselves, Konto 55-gō chased and reinforced the proliferation of what Allan Kaprow described as ‘Happening.’ Originally coined in 1959 in reference to art-related events in which the artist took on theatrical directions and modes of expression, Happenings flourished throughout the United States through the 1950s and 1960s, spreading globally but predominantly in Germany and Japan.[26] In the context of the Japanese television industry, ‘Happening’ was co-opted to refer to anything unscripted — quite the opposite from its intent as a label for deliberate performance — after the early 1968 program Kijima Norio Happuningu Sho (“Kijima Norio’s Happening Show”).[27] To be clear, Happenings in this context were still partially staged just as art Happenings were, but the intent from producers was that Happenings would go off the rails by virtue of a lack of scripting and the co-operation and involvement of audience participants. As other shows and producers chased this spontaneity and carried in the wake of Konto 55-gō’s pioneering transgressions, the stakes became higher and content needed to become more compelling, more novel, more edgy, more risque.

The most critical apex of Happening for our purposes came in 1969 on Konto 55-gō no Urabangumi o Buttobase (“Konto 55-gō Blow away the competition”). It was here that Yakyūken was introduced as a segment of the program, with Kinichi and Jirō facing off against numerous women, each stripping an article of clothing upon a loss. Removed articles were then auctioned to raise funds for children orphaned by traffic accidents.[28] The segment was an enormous hit among adults and children, some critics praising this nakedness as incredibly real, the pinnacle of the Happening.[29] At the same time, just as with all of Konto 55-gō’s antics, many loathed this primetime strip tease wholly inappropriate for children to view, some citing it as a siege against one of the sole bulwarks left against Japan’s growing moral decline, the home.[30] Scorn came not only from without, however, but within as well. Kinichi would later go on to say Konto 55-gō no Urabangumi o Buttobase was his most disliked programme he ever worked on, in no small part due to the Yakyūken segment which brought viewers in not for the comedy of the duo, but for the titillation and obscenity of the Yakyūken act itself.[31] Furthermore, in 2005, Kinichi visited Matsuyama to apologise personally to fourth honke Yakyūken iemoto Tsuyoshitoshi Sawada for misrepresenting Yakyūken. Despite this resentment from Kinichi and some critics, Yakyūken reinvigorated jan-ken into a game with stakes, with merriment, with rules everyone was already familiar with, with a catchy song and dance, that brought the Happening into the real world.

Through Konto 55-gō’s work, Yakyūken presented the same problem that chonkina had in the previous century — a breaking of the boundaries between adult entertainment and the recreation of children. This was no longer bound to the district of Asakusa, but the whole of Japan. Further still, the growing popularity of Yakyūken and its association with Konto 55-gō spread the popular conception of the dance originating as a strip performance, rendering the attempts of Tanuki’s iemoto system to preserve the sanctity of Maeda’s original work increasingly ineffective. The iemoto system only had merit when the associated act could be considered a tradition worth preserving such as tea ceremony or calligraphy. With Yakyūken compromising the cultural zeitgeist as a strip game, it became difficult to consider it a valuable cultural commodity. While it is possible this was the greater underlying reason for Matsuyama’s introduction of Yakyūken Odori to the Matsuyama Odori festival in 1970, it cannot be stated as certainty. What was certain was that Yakyūken was here to stay as a television staple, at least for a moment.

Yakyūken remained a part of Konto 55-gō no Urabangumi o Buttobase through to the end of 1969, afterwards being spun-off into its own program Konto 55-gō no Yakyūken!! From November 26, 1969, thirty minutes of strip rock-paper-scissors littered the airwaves every Wednesday at 9PM until the program was discontinued in April 1970.[32] Yakyūken would not be broadcast on Nippon TV for another two decades, returning on New Year’s Eve, 1993 as part of Supa Denpa Bazaru Toshikoshi Janbo Dosokai (“Super Radio Bazaar New Year’s Jumbo Alumni Reunion”). Though no longer televised in the interim, Yakyūken remained in the cultural zeitgeist as a strip game. While impossible to discern at what point Yakyūken became a mainstay of Japanese pornographic production, it has become ubiquitous — a cursory search of Japanese pornographic clip site eroterest.net gives over 34,000 results for Yakyūken. What is certain is that Yakyūken similarly became not just a mainstay of Japanese erotic video games, but the foundation of the entire industry.

In Which I Finally Tell You About the Video Game Yakyūken by Hudson Soft

With 500,000 yen in starting capital, brothers Yūji and Hiroshi Kudō founded Hudson Co., Ltd. in Toyohira-ku, Sapporo on May 18, 1973. Named after the duo’s favourite class of train, the 4-6-4 Hudson, Yūji and Hiroshi sold fine art photographs of locomotives. In September, the brothers opened a dedicated amateur radio shop, CQ Hudson, which stood at 3-7-26, Hiragishi, Toyohira-ku into the new millennium.[33] After travelling to the US shortly thereafter to market their wares, Yūji saw personal computers on general sale for the first time, inspiring him to bring home a PolyMorphic Systems Poly-88 to Japan and learn to program, taking on two million yen in credit card debt to finance the purchase.[34] Well before the personal computer revolution hit Japan, The Kudō brothers were pioneers. The shops of Akihabara bore no fruit for them, necessitating the Poly-88 import. By 1975, the Kudōs had fully branched out into personal computer products, turning type-in programs into pre-packaged cassette tape releases for the sake of convenience, and becoming early adopters of NEC’s 1976 TK-80 and Sharp’s MZ-80 line of computers.[35] The Kudō brothers also began to start writing their own programs around this time under the development team name Miso Ramen Group.

Hudson released at least thirty-seven games for the MZ-80 line, available occasionally as type-ins in magazines like Micom or in books like MZ-80B活用研究. There was a little bit of everything in Miso Ramen Group’s offerings, from the Maze War-esque Ramen Maze 3D to Othello to Operation Escape, wherein the player had to sneak out of class not unlike Konami’s 1984 Beatles-laden Mikie.[36] In the summer of 1979, Hudson was approached by a computer manufacturer with a proposal to sell their software by mail order with an advertisement in Micom for July 1979.[37] The ads were a success, with the Kudōs recounting later that deposits at the bank took upwards of thirty minutes because tellers thought they might be criminals.[38] Yakyūken’s existence in this initial advertisement makes it plain that the game was developed prior to mid-1979, and the ad was laid bare in a 1996 television documentary special by NHK. Yet Yakyūken’s status as the first commercial erotic game seems to have fallen to the wayside.

The game is incredibly simple, as one might expect from a preliminary type-in program from the late 1970s.[39] The player decides how many articles of clothing they wish themselves to have, not dissimilar from a lives system, and is then introduced to their opponent, Megumi.

わたしめぐみよろしくね。(“I’m Megumi, nice to meet you.”)

A few bars of the Yakyūken song beep languidly from the piezoelectric speaker with a bold OUT!! SAFE!! ヨヨイノヨイ covering the screen. The player chooses グ (rock), チョキ (scissors), or パ (paper). In the event of a tie, the process repeats. Should the player lose, an article of clothing is theoretically removed with no visual indication. Should they win, Megumi is declared ‘out’ and her avatar removes an article of clothing. Shirt, skirt, bra, panties. An eyebrow is cocked when her outer attire comes off, the other joining in twain when her bra comes loose. When she loses her panties, Megumi covers her crotch and shrieks "キャー!!はやくあっちへいって!!" (“Kyaa! Quickly, get out!!”) Game end. The original MZ-80 release was monochromatic, but the later MZ-700 versions were in colour, used to minimal effect. It really is as simple as that.

Who’s on first?

Koei’s first entry in their Strawberry Porno series, Night Life, dominates much of the historical record as the earliest erotic game, particularly in the West. Hardcore Gaming 101, Matthew T. Jones, Wikipedia, and MobyGames (among others) authoritatively claim it to be the first, and on occasion one might see PSK’s Lolita Yakyūken cited in its place, but both works released in 1982, the same year as Custer’s Revenge.[40] ASCII Corporation’s history of the NEC PC-8801 show similar family trees wherein Night Life is the root of all Japanese eroge, its own ancestor being On-Line Systems’ 1981 Softporn Adventure.[41] So too does Pasokon Super Special PC Game 80s Chronicle.[42] When Yakyūken is mentioned by these sources, it is as a possibility, something which might be true but lacks veracity, yet the evidence is plain.

Perhaps Yakyūken was simply too early, releasing before heavy-hitter platforms like the NEC PC-88 or Fujitsu FM-7. The MZ-80 line’s flagship was the MZ-80K, released in 1978. It was available only as an assembly kit, which, coupled with its high retail price of ¥198,000, left it in the realm of the enthusiast and academic (particularly engineering students).[43] While games were blatantly possible on the platform, they were far from the focus, limiting the audience for Hudson’s games, particularly Yakyūken, dramatically. Further still, it was sold primarily through mail order, advertised in niche magazines without pictures. Hudson got paid, and quite well at that, but orders came for a litany of their products. Without knowing this was an explicit game, the prospect of playing digital jan-ken must have paled in comparison to Othello or Hudson’s more arcade-style offerings. By the time it came to the next generation on 1982’s MZ-700, the floodgates had already been opened, and platforms capable of graphics dominated the eroge space.

Perhaps Night Life and Lolita Yakyūken take the historiographical spotlight because they lack the primitiveness of Yakyūken. There is no denying that Yakyūken lacks the graphical fidelity of its descendants. Bound by the 80 column by 50 row display of the MZ-80K, space is limited, colour an impossibility, and everything is comprised of text characters as the hardware could not display graphics. The Japanese character ROM bears no curvilinear shapes apart from circles.[44] The hand signs are malformed, and though your opponent, doesn’t look bad per se, her rectangular body’s attempt at an hourglass figure is not exactly stunning. As games writer Yoshiki Osawa described it in the 2000 book Bisyoujyo Game Maniax, [sic] the visuals lack gender specificity, and exhibit a crudeness that cannot even be called ASCII art.[45] Compared to the full colour illustrations of PSK’s Lolita Yakyūken or even the silhouettes of Night Life, Yakyūken comes up short.

Perhaps Yakyūken was too outdated to catch on without some additional gimmick such as lolicon artwork. The original dance craze had occurred a quarter-century earlier, and it had been barred from television for nearly a decade. By the admission of MZ-700 Joyful Pack, Yakyūken was unlikely to resonate with those who did not grow up in the postwar period. A craze to be sure, but a craze for a generation past, one which had little interest in computing. The type-in’s accompanying text even had to make explicit that Yakyūken had virtually nothing to do with baseball, despite its name, as well as the fact this was a game of chonkina.

What these comparisons ignore is that stunning the world was not necessarily Yakyūken’s purpose. Though sold commercially, projects in its vein from Hudson were as much at home on cassette as they were printed as type-ins. By having their code laid entirely bare, type-ins meant hobbyists dabbling in a brand new technology could visually see and alter the program. The type-in’s purpose was to demonstrate what a computer could do. A user could change Megumi-chan into a man, increase her bust size, style her hair. Perhaps they could do away with jan-ken and replace its symbols with those from Touhachi-ken. Why not increase the number of options available for some digital Rock Paper Scissors Lizard Spock? Just as type-ins are used to teach today, so were they then — deliberately open ecosystems in which to learn. Night Life and Lolita Yakyūken were as walled gardens, the magic unable to be discerned.

In Which I Admit This is All Pedantry and Ultimately Does Not Matter

The fact of the matter is that this is all pedantry and ultimately it does not matter. While monumental firsts are readily recorded, the more niche the subject matter, the more abstruse the truth of a first becomes. Any history student can tell you this after a course on historiography and the historical method. The fact of the matter is that what comes first is arbitrary, determined by fallible, biased humans trying to further an argument.

The search for historical firsts has overtaken much of contemporary historical scholarship, and the problem with this is that there is invariably always an earlier example, and the argument of something as coming earlier is increasingly valueless. Certainly there will always come a true first, but how can we know it is certain with an always imperfect historical record? Does it matter if something came first if it was too ahead of its time? Would we be better off as historians focusing more on moments of critical mass as others in adjacent fields do, such as Marek Zvelebil did in his research on agricultural innovations in the archaeological record?[46] Who is to say. What I can say for sure is that I sincerely hope Yakyūken is not the first commercial erotic game. I hope to be disproved at some point in the future. I hope that in trying to set the record straight in this one instance, it can be set straight in another. I hope the drive for better histories never ends, and that at some point we can dwell less on firsts, and more on more critical narratives in games history, cultural history, human history.

__________________________

[1] Video Games Densetsu, “Yakyūken / 野球拳, Probably the First Erotic Video Game Ever Released.,” Tumblr, November 18, 2016, https://videogamesdensetsu.tumblr.com/post/153336334460/yaky%C5%ABken-%E9%87%8E%E7%90%83%E6%8B%B3-probably-the-first-erotic-video.

[2] “【宅配買取】MZ-700用野球拳(ハドソン)を宮城県仙台市のお客様よりお譲りいただきました|BEEP,” BEEP, April 16, 2019, http://www.beep-shop.com/blog/5921/.

[3] “Hudson Soft - HuPack #2 (Featuring Rowdy-Ball and Yakyūken)(Scans + GameRip) : Hudson Soft,” Internet Archive, July 1, 2023, https://archive.org/details/Hudson-soft-hupack-2.

[4] Sepp Linhart, From Kendô to Jan-Ken: The Deterioration of a Game from Exoticism into Ordinariness (SUNY Press, 1998), 322-323.

[5] Sepp Linhart, “Rituality in the Ken Game,” Ceremony and Ritual in Japan, (2013): 39. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203429549-10.

[6] Linhart, “Rituality in the Ken Game,” 39.

[7] Kitamura Nobuyo. 1933. Kiyu shoran. 2 vols. Tokyo: Seikokan shoten, quoted in Linhart, From Kendô to Jan-Ken, 325.

[8] Stewart Culin, Korean Games with Notes on the Corresponding Games of China and Japan (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1895), 46-47.

[9] Shibuzawa Seika. 1966. Asakusakko. Tokyo: Zoukeisha, quoted in Linhart, From Kendô to Jan-Ken, 334-335.

[10] Hironori Takahashi, “Japanese fist games” (in Japanese): Osaka University of Commerce Amusement Industry Research Institute (2014): 203.

[11] Thomas Crump, Japanese Numbers Game (London: Routledge, 1992). 146.

[12] “本当は脱がない「野球拳」 松山発祥、90年の歴史,” 日本経済新聞, June 29, 2014, https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXNASFG230DO_V20C14A6BC8000/. Accounts seem to differ on the final score, with some sources claiming it was a 0-6 defeat, others 0-8. As 0-8 is cited by the fourth Iemoto of Yakyūken, that is the number I have decided to use.

[13] Takakashi, “Japanese fist games,” 204-205.

[14] Takakashi, “Japanese fist games,” 204-205.

[15] Takao Ohashi, “A Trademark Registration for ‘野球拳おどり’ (Yakyu-Ken Dance ) - パークス法律事務所,” パークス法律事務所 -, December 9, 2021, https://pax.law/topics/blog/1242/.

[16] 野球けん 若原一郎・照菊, YouTube (YouTube, 2023), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H58uhkoQrbo.

[17] 久保幸江・高倉敏 野球拳, YouTube (YouTube, 2015), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Xdfh4dBWeM.

[18] 靑木 はるみ ♪野球けん♪ 1954年 78rpm Record. Columbia Model No G ー 241 Phonograph, YouTube (YouTube, 2022), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ycCAK69hc7w.

[19] “本家 野球拳,” GMOとくとくBB|運営実績20年以上のおトクなプロバイダー, accessed October 2, 2023, http://shikoku.me/iyo-matsuri/raijin/honkeyakyuuken/history/index.html.

[20] “松山野球拳おどりのあゆみ,” 松山野球拳おどり 公式ホームページ, accessed October 2, 2023, https://baseball-dance.com/about/story/.

[21] David Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday: Konto 55-gō and the Teleivision Comedy of the Late 60s” Japan Studies Association Journal 15, no. 1 (2017): 24.

[22] Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday,” 24.

[23] Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday,” 28.

[24] Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday,” 28-30.

[25] Harumi Setouchi, “Tondari hanetari… Konto 55-gō no gei to sugao,” Oh! (August 1968): 176-177, quoted in Humphrey: “Shattering the Everyday,” 30.

[26] Allan Kaprow, “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock (1958),” in Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 1-9.

[27] Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday,” 32.

[28] “欽ちゃん「もっとも嫌いな番組だった」 2人の芸風の違いが浮き彫りになった「裏番組をぶっとばせ!」,” イザ!, September 4, 2018, https://www.iza.ne.jp/article/20180904-HGNF6BYZ5VLH5CV54ZLQFEC2MA/.

[29] Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday,” 36-37.

[30] Humphrey, “Shattering the Everyday,” 37.

[31] イザ!, “欽ちゃん”

[32] マスコミ市民 : ジャーナリストと市民を結ぶ情報誌 (36)

[33] “Company Information,” Hudson Soft, December 11, 2000, Internet Archive, https://web.archive.org/web/20001211040400/http://www.hudson.co.jp:80/coinfo/history.html; Brian Eddy, “Video Game History 101: Hudson Soft,” New Retro Wave, January 30, 2017, https://newretrowave.com/2017/01/30/video-game-history-101-hudson-soft/.

[34] Damien McFerran, “Hudson Profile — Part 1,” Retro Gamer Magazine 66, (2009): 68; スペシャル 新・電子立国 第4回 「ビデオゲーム」 ~巨富の攻防~ (NHK, 1996), streaming video, 40:16, Internet Archive. There are conflicting accounts on why Yūji went to the United States and what his first computer was. The information cited here comes from an interview with Yūji himself. Doug Carlston claims that his first computer was actually a SBC80, followed by an IMSAI, but I have not found further evidence to support this claim. See Doug Carlston, Software People: Inside the Computer Business (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985), 253-257.

[35] The specifics of the timeline become unclear around this time; Japanese microcomputers weren’t commercially available for consumers until mid-1976, yet Hudson’s own company history has them pegged as making PC cassettes and equipment in September 1975.