Detchibe

BACKER

1990

Pretty good erotic pixel art under a tissue paper-thin veil of gameplay that is outclassed by nearly the entire X68000 library. You walk forward in a straight line, enemies spawn in abundance in front of and behind you, you punch or kick them, repeat until you get to a boss. The grotesque disfigurements of these putty women in the core game belie the print materials and slideshow rewards for beating a stage. Though ostensibly these are lesbian displays of lewdness, they cater to the male gaze with laser precision with both parties taking on stances of submission and presentation towards the camera.

Not that this a-phallic focus is of any surprise. Published under the Technopolis Soft label, a software imprint of Tokuma Shoten's Technopolis magazine, this material reflects the contents of this and other Japanese PC enthusiast magazines of the 80s and 90s. Whether it's Technopolis, POPCOM, LOGiN, these magazines and their ilk catered to an overwhelmingly male readership. Entire sections of these and other magazines were devoted to eroge, gravure photoshoots, and erotic manga. In Guerrière Lyewärd, as in Technopolis itself, lesbian imagery is not on display as a means of some liberation for repressed women loving women in Japan, but a fetishistic object for heterosexual consumption. These women are crazed nymphomaniacs in need of a satiation which never comes.

Pornography aside, this is one of the shallowest eroge I've ever played, both in terms of erotic content and the gameplay itself. I thought maybe it was a type-in game, or a pack-in from a Technopolis appendix. No! It physically released! It cost 6800円! That's around $110USD today! That's like $5 for every 'lewd' image, goddamn!!!

Not that this a-phallic focus is of any surprise. Published under the Technopolis Soft label, a software imprint of Tokuma Shoten's Technopolis magazine, this material reflects the contents of this and other Japanese PC enthusiast magazines of the 80s and 90s. Whether it's Technopolis, POPCOM, LOGiN, these magazines and their ilk catered to an overwhelmingly male readership. Entire sections of these and other magazines were devoted to eroge, gravure photoshoots, and erotic manga. In Guerrière Lyewärd, as in Technopolis itself, lesbian imagery is not on display as a means of some liberation for repressed women loving women in Japan, but a fetishistic object for heterosexual consumption. These women are crazed nymphomaniacs in need of a satiation which never comes.

Pornography aside, this is one of the shallowest eroge I've ever played, both in terms of erotic content and the gameplay itself. I thought maybe it was a type-in game, or a pack-in from a Technopolis appendix. No! It physically released! It cost 6800円! That's around $110USD today! That's like $5 for every 'lewd' image, goddamn!!!

While Cook, Serve, Delicious! was already one of my favourite games, small things about it left me wanting more. The food options were very limited, there was little variation between days, and progression boiled down to how many days you completed rather than your skill. Despite that, CSD! is so unique that it's hard to find other games like it.

I was incredibly hyped for Cook, Serve, Delicious! 2!! prior to release, but was put off by the changes to the formula. Recipes couldn't be carried out rapid-fire if you remembered the keys, you had to press a key to go to the next page of steps. The menus and level select were obtuse to the point where I had to click blindly to navigate. The preset menus of the restaurants were brilliant as scripted level sequences, but made it difficult to justify working in my own restaurant when that contract work felt like the 'real game'. Unlocking new foods felt incredibly slow. Serving more customers faster than ever was problematised by the need to still hit specific keys to start and serve orders, and that speed made slip ups way more common. The continuation of chores didn't mesh with the new rapidity. Customising the restaurant was cool but I was also inundated with cosmetic unlocks I didn't feel like using because, again, I didn't feel compelled to work in my own restaurant. I return to CSD frequently, but CSD2 felt like experiencing Icarus flying too close to the sun.

When I saw Cook, Serve, Delicious! 3?! was in Early Access I was delighted but hesitant to give it a shot having been disappointed before, but it has surpassed both CSD2 and CSD in terms of quality. The story is not on the same level as the likes of LISA or Disco Elysium, though it is serviceable and interesting (I definitely did some Wiki deepdiving to find out about The Blue War and what happened to Japan). The voice acting is cute and I still love the hums the customers make. I was surprised to find that the soundtrack was composed by the same artist as the previous games since the step up in production and general quality is incredible. CSD and CSD2 had good soundtracks to be sure, but CSD3 has bops that are stuck in my head and occupy my Spotify playlists.

The design of CSD3's gameplay is virtually without flaw, retaining the best aspects of the previous instalments with its own important and unique additions.

Chores are completely gone (unless you count clearing your service stations due to rot or the level ending - gotta hear that satisfying ka-chunk) meaning my cooking rhythm isn't interrupted by mashing the arrow keys while patience rapidly ticks down.

The new Auto Serve key allows the breakneck speed of CSD2 without the heartbreak of accidentally pushing the key for something you just started cooking. You're saved from the potential hearing damage that everything going off at once would cause since it quickly 'scrolls' through the available dishes for an intensely satisfying series of chimes. And it doesn't save you from having to complete a dish, it simply helps push out things that would normally require a simple key press. It's small in theory but it goes a long way towards maintaining the 'flow' of CSD. Making some of the more complicated dishes was hard enough without having to hunt down dishes ready to go.

One still has to navigate through pages of ingredients as in CSD2, but the removal of side dish juggling and addition of Auto Serve makes this is less stressful. You can also change the colors of the page indicators!

Delicious ratings are less of a hassle to collect as they simply replace your Great ratings once you hit a certain combo of perfect dishes - no more worrying about having side dishes prepped in your incredibly important Holding Stations.

Chill mode still makes you feel incredible for doing well and serves as a good set of low-shame training wheels while you learn the game or try out new recipes. For the first few regions of the game I stayed on Chill and didn't feel like I was 'wussing out' of the 'real' experience at all. Not getting Gold Medals (you're locked to Silver if you play on Chill) does mean some levels can't be accessed without playing on Standard at least a bit, but the plethora of levels means you can still progress through the story and the vast majority of the levels. Those tied behind Gold Medals are usually some of the hardest challenges in the game. The 'choose your own difficulty' manner of the CSD series' menu configurations means you could probably replicate similar circumstances on another level if you really wanted - I can't speak for how missing out on this small subset of content in an official capacity might feel for those unable to access it.

Unlike CSD and CSD2, it's not difficult to earn the game's currency, which means it's easy to unlock the foods you want, and it gets easier as you rack up more difficult and expensive foods. Decorations now serve as a sink for any remaining currency, though power players like myself barely have a dent put in our virtual wallets.

It's nice not having foods 'taken away' from you once you reach a certain point like in CSD, your access to food will remain. While each level presents certain menu categories, I assure you you'll be able to make Brownies again, whereas in CSD you will eventually make your last Corn Dog long before the game ends.

Upgrading your truck makes the game more manageable but also allows more difficult situations to be created through additional Holding/Prep Stations. For example, the upgrade which refreshes Holding Station freshness and gives you back some servings for finishing a stop lets you focus more on special orders but also incentivises more 'aggressive' play.

The food truck is absolutely genius when it comes to game pacing. In CSD you had slow periods, quite frankly, all the time, even with 100% buzz. The food truck has you constantly cooking. Special Orders come in a constant, steady stream between stops, and your Holding Stations always feel like they could be better optimised if you do have a gap between Special Orders. The routes (but not the days for the route) always have the same number of customers across all their days, and they share the number of stops and the distance. If you obsess over replaying the levels like I do, you'll start to remember how things will be spaced out so you can plan better.

The food truck attacks start as minor inconveniences but by mid-to-late game they provide exhilarating challenges. Losing a holding station or two is one thing, losing all the contents of them is another. Not seeing upcoming Holding Station orders isn't the end of the world, not seeing what any of your orders are ensures you have a good grasp of your menu. The endgame attack which removes your upgrades is brutal but incredibly fun.

The addition of the Iron Cook Speedway has cemented CSD3?!'s magnificence by eliminating my only real gripe with the game - the ease of complacency. As is inevitable for most games, one can easily fall back on dominant strategy, in CSD3?!'s case that being focusing on auto-served foods with high point to skill/time ratios (Calzones and Tamales exemplify this, they have no right to be 5-point dishes given how simple they are to execute). By the end of the game with a maxed-out food truck, attacks are a nonissue as you can simply disable them, and save for some scenarios where you can only do menus with no auto-served dishes, or niche challenge levels where you have to use foods you might not have memorised (looking at you King Potatoes), levels begin to bleed together.

The Iron Cook Speedway rectifies this by offering the CSD franchise's truest challenge yet by simply taking away the ability to nullify attacks, and by stacking those attacks on top of each other.

Making foods that are engraved in my memory is not as reliable as it once was because I'm now doing the recipes in addition to things like invisible cook timers AND shorter holding station freshness AND losing some of those holding stations. Where I could once kind of fumble through some recipes I now have to execute them quickly and perfectly. Furthermore, as is already seen in some of the later cities, you are given weirder and more narrow options for constructing your menus which means learning a wider variety of foods and getting into different rhythms.

The Iron Cook Speedway is effectively the Star World of CSD3?!, a place to demonstrate mastery. Chill mode remains an option as ever meaning it should be possible for anyone to get through the final chapter but it will only be the best of the best chefs who get all Gold.

Like Lasagne or Medoviks, at last we see what happens when layers upon layers of intricacies come together to make a perfect whole.

There are so many other little things that have me in love with CSD3. The food (carried over in part from CSD2) looks incredibly appetising yet still stylised. The accessibility options alleviate the concerns I had about the food truck moving causing motion sickness - you can have things be perfectly still. The sounds that accompany food prep are like little rushes of dopamine. While the writing is mostly farcical fiction, I've still learned so much about food I didn't even know existed. Adding on the little modifiers and challenges as well as mixing up the menu options really makes every level feel fresh. It's also possible to mute the police sirens and gunfire, a minor but important option given the zeitgeist of its release in mid-2020.

David Galindo hopefully hasn't peaked with this entry, but if he has it's a magnificent apex.

I was incredibly hyped for Cook, Serve, Delicious! 2!! prior to release, but was put off by the changes to the formula. Recipes couldn't be carried out rapid-fire if you remembered the keys, you had to press a key to go to the next page of steps. The menus and level select were obtuse to the point where I had to click blindly to navigate. The preset menus of the restaurants were brilliant as scripted level sequences, but made it difficult to justify working in my own restaurant when that contract work felt like the 'real game'. Unlocking new foods felt incredibly slow. Serving more customers faster than ever was problematised by the need to still hit specific keys to start and serve orders, and that speed made slip ups way more common. The continuation of chores didn't mesh with the new rapidity. Customising the restaurant was cool but I was also inundated with cosmetic unlocks I didn't feel like using because, again, I didn't feel compelled to work in my own restaurant. I return to CSD frequently, but CSD2 felt like experiencing Icarus flying too close to the sun.

When I saw Cook, Serve, Delicious! 3?! was in Early Access I was delighted but hesitant to give it a shot having been disappointed before, but it has surpassed both CSD2 and CSD in terms of quality. The story is not on the same level as the likes of LISA or Disco Elysium, though it is serviceable and interesting (I definitely did some Wiki deepdiving to find out about The Blue War and what happened to Japan). The voice acting is cute and I still love the hums the customers make. I was surprised to find that the soundtrack was composed by the same artist as the previous games since the step up in production and general quality is incredible. CSD and CSD2 had good soundtracks to be sure, but CSD3 has bops that are stuck in my head and occupy my Spotify playlists.

The design of CSD3's gameplay is virtually without flaw, retaining the best aspects of the previous instalments with its own important and unique additions.

Chores are completely gone (unless you count clearing your service stations due to rot or the level ending - gotta hear that satisfying ka-chunk) meaning my cooking rhythm isn't interrupted by mashing the arrow keys while patience rapidly ticks down.

The new Auto Serve key allows the breakneck speed of CSD2 without the heartbreak of accidentally pushing the key for something you just started cooking. You're saved from the potential hearing damage that everything going off at once would cause since it quickly 'scrolls' through the available dishes for an intensely satisfying series of chimes. And it doesn't save you from having to complete a dish, it simply helps push out things that would normally require a simple key press. It's small in theory but it goes a long way towards maintaining the 'flow' of CSD. Making some of the more complicated dishes was hard enough without having to hunt down dishes ready to go.

One still has to navigate through pages of ingredients as in CSD2, but the removal of side dish juggling and addition of Auto Serve makes this is less stressful. You can also change the colors of the page indicators!

Delicious ratings are less of a hassle to collect as they simply replace your Great ratings once you hit a certain combo of perfect dishes - no more worrying about having side dishes prepped in your incredibly important Holding Stations.

Chill mode still makes you feel incredible for doing well and serves as a good set of low-shame training wheels while you learn the game or try out new recipes. For the first few regions of the game I stayed on Chill and didn't feel like I was 'wussing out' of the 'real' experience at all. Not getting Gold Medals (you're locked to Silver if you play on Chill) does mean some levels can't be accessed without playing on Standard at least a bit, but the plethora of levels means you can still progress through the story and the vast majority of the levels. Those tied behind Gold Medals are usually some of the hardest challenges in the game. The 'choose your own difficulty' manner of the CSD series' menu configurations means you could probably replicate similar circumstances on another level if you really wanted - I can't speak for how missing out on this small subset of content in an official capacity might feel for those unable to access it.

Unlike CSD and CSD2, it's not difficult to earn the game's currency, which means it's easy to unlock the foods you want, and it gets easier as you rack up more difficult and expensive foods. Decorations now serve as a sink for any remaining currency, though power players like myself barely have a dent put in our virtual wallets.

It's nice not having foods 'taken away' from you once you reach a certain point like in CSD, your access to food will remain. While each level presents certain menu categories, I assure you you'll be able to make Brownies again, whereas in CSD you will eventually make your last Corn Dog long before the game ends.

Upgrading your truck makes the game more manageable but also allows more difficult situations to be created through additional Holding/Prep Stations. For example, the upgrade which refreshes Holding Station freshness and gives you back some servings for finishing a stop lets you focus more on special orders but also incentivises more 'aggressive' play.

The food truck is absolutely genius when it comes to game pacing. In CSD you had slow periods, quite frankly, all the time, even with 100% buzz. The food truck has you constantly cooking. Special Orders come in a constant, steady stream between stops, and your Holding Stations always feel like they could be better optimised if you do have a gap between Special Orders. The routes (but not the days for the route) always have the same number of customers across all their days, and they share the number of stops and the distance. If you obsess over replaying the levels like I do, you'll start to remember how things will be spaced out so you can plan better.

The food truck attacks start as minor inconveniences but by mid-to-late game they provide exhilarating challenges. Losing a holding station or two is one thing, losing all the contents of them is another. Not seeing upcoming Holding Station orders isn't the end of the world, not seeing what any of your orders are ensures you have a good grasp of your menu. The endgame attack which removes your upgrades is brutal but incredibly fun.

The addition of the Iron Cook Speedway has cemented CSD3?!'s magnificence by eliminating my only real gripe with the game - the ease of complacency. As is inevitable for most games, one can easily fall back on dominant strategy, in CSD3?!'s case that being focusing on auto-served foods with high point to skill/time ratios (Calzones and Tamales exemplify this, they have no right to be 5-point dishes given how simple they are to execute). By the end of the game with a maxed-out food truck, attacks are a nonissue as you can simply disable them, and save for some scenarios where you can only do menus with no auto-served dishes, or niche challenge levels where you have to use foods you might not have memorised (looking at you King Potatoes), levels begin to bleed together.

The Iron Cook Speedway rectifies this by offering the CSD franchise's truest challenge yet by simply taking away the ability to nullify attacks, and by stacking those attacks on top of each other.

Making foods that are engraved in my memory is not as reliable as it once was because I'm now doing the recipes in addition to things like invisible cook timers AND shorter holding station freshness AND losing some of those holding stations. Where I could once kind of fumble through some recipes I now have to execute them quickly and perfectly. Furthermore, as is already seen in some of the later cities, you are given weirder and more narrow options for constructing your menus which means learning a wider variety of foods and getting into different rhythms.

The Iron Cook Speedway is effectively the Star World of CSD3?!, a place to demonstrate mastery. Chill mode remains an option as ever meaning it should be possible for anyone to get through the final chapter but it will only be the best of the best chefs who get all Gold.

Like Lasagne or Medoviks, at last we see what happens when layers upon layers of intricacies come together to make a perfect whole.

There are so many other little things that have me in love with CSD3. The food (carried over in part from CSD2) looks incredibly appetising yet still stylised. The accessibility options alleviate the concerns I had about the food truck moving causing motion sickness - you can have things be perfectly still. The sounds that accompany food prep are like little rushes of dopamine. While the writing is mostly farcical fiction, I've still learned so much about food I didn't even know existed. Adding on the little modifiers and challenges as well as mixing up the menu options really makes every level feel fresh. It's also possible to mute the police sirens and gunfire, a minor but important option given the zeitgeist of its release in mid-2020.

David Galindo hopefully hasn't peaked with this entry, but if he has it's a magnificent apex.

With my teeth cut on the herculean likes of Castlevania: The Adventure and Geograph Seal, and without any deep-seated adoration for Super Mario Bros. it must come as little surprise I not only liked Super Mario Bros. Special, but outright loved it by the end. On a technical, graphical, audio, mechanical, and ludological level, SMBS is a whisper of a shadow of the Nintendo original. Despite the odds being stacked astronomically against them, however, the team at Hudson crafted something that becomes an earnest marvel. SMBS effectively parcels out the essence of SMB in single-screen microdoses of platforming not too dissimilar to Prince of Persia, N++, or Dizzy.

This limitation informed decision would fail utterly with the mechanics and physics of SMB, but SMBS' tweaks accommodate this well. With the exception of multi-screen jumps, each segment can stand on its own as a mini-level effectively disconnected from those surrounding it. In theory, this would be jarring and discordant. In practice, those self-contained bits and bobs ensure each challenge is approached from common ground under the assumption that the player might have zero momentum at the start. Both cautious and bold players benefit from this, the former is not punished for slowing down, the latter barely hindered by the transition between screens. With the peculiarities of the physics and controls, this seems outright necessary. Mario jumps like he's taking inspiration from Simon Belmont, his running stops if too many keyboard keys are pressed (ie. two), he has the inertia of a semi-truck loaded with tungsten. Getting a grip on this bizarro setup is an agony in itself, but a rewarding one when enormous chasms are eventually crossed without hesitation.

Also due to limitations is the inconsistent game speed. Playing at the default 4MHz clock speed of the Sharp X1, everything drips like pitch if Mario is Super and too many sprites are on screen (ie. two). If Mario is Small or absent from the screen, everything is entirely too fast, even by the standards of SMB. This drunken sway between two extremes is uncomfortable to listen too and uneven to play. However, it unintentionally presents the player a variety of ways with which to engage with the game. Should the player go Super or Fiery, the experience is slower but perhaps intended. Clearing enemies and obstacles makes the screens accelerate near their ends. If the player goes Super or Fiery and ensures they keep as many sprites on screen at once, the game slows further to allow greater precision in platforming on that screen. The safety net of not being Small Mario makes these two options the most lackadaisical. On the other hand, Small Mario makes the game run, if not fast, at least at a consistently higher speed. Jumps thereby become tighter, and Mario much more vulnerable. Clearing enemies and obstacles makes the screens accelerate near their ends, so a bold player can take their chances and double down on them to proceed as quickly as possible. On paper this is perhaps a meaningless choice, but in practice there arises a genuine balancing act of choosing whether or not to bother with power-ups, with clearing enemies, with going fast. By the end of my playthrough, I consistently stayed as Small Mario and threw caution to the wind, making for a tense but rewarding experience.

The (re-)introduction of enemies from Donkey Kong and Mario Bros. are icing on an absurd cake, their inclusion an anachronistic anomaly that presents just enough of a shift in player approach to be meaningful. Sidesteppers may serve an identical purpose to Spinies, but Fighterflies' hops, barrels' rolling, fireballs' outright immunity, and the imminent hazard of icicles all carve out niches of their own without being out of place.

Separately, every facet of Super Mario Bros. Special fails to cut the mustard. As a synthesis, it is remarkable. My victory genuinely felt like it had been hard won from some overwhelming force. The Geiger–Müller counter buzzing was a constant companion I grew fond of. The words of Princess Peach rang clear and true: "You cleared every world. You are the greatest player. Congraturations!" [sic]

I would never recommend anyone play Super Mario Bros. Special without the most open of minds, and even then I think most will get their fill by the time they clear World 1. Maybe I'm too sick in the head to interpret this as a 'bad' game. Maybe I'm to sick to see it as anything but amazing. Either way, its eight worlds sought to chew me up and spit me out. Instead, I prevailed.

This is not a Super Mario Bros. Special as the actual name suggests. The title screen and box make the true meaning subtly known. This is a Super Special Mario Bros. game.

This limitation informed decision would fail utterly with the mechanics and physics of SMB, but SMBS' tweaks accommodate this well. With the exception of multi-screen jumps, each segment can stand on its own as a mini-level effectively disconnected from those surrounding it. In theory, this would be jarring and discordant. In practice, those self-contained bits and bobs ensure each challenge is approached from common ground under the assumption that the player might have zero momentum at the start. Both cautious and bold players benefit from this, the former is not punished for slowing down, the latter barely hindered by the transition between screens. With the peculiarities of the physics and controls, this seems outright necessary. Mario jumps like he's taking inspiration from Simon Belmont, his running stops if too many keyboard keys are pressed (ie. two), he has the inertia of a semi-truck loaded with tungsten. Getting a grip on this bizarro setup is an agony in itself, but a rewarding one when enormous chasms are eventually crossed without hesitation.

Also due to limitations is the inconsistent game speed. Playing at the default 4MHz clock speed of the Sharp X1, everything drips like pitch if Mario is Super and too many sprites are on screen (ie. two). If Mario is Small or absent from the screen, everything is entirely too fast, even by the standards of SMB. This drunken sway between two extremes is uncomfortable to listen too and uneven to play. However, it unintentionally presents the player a variety of ways with which to engage with the game. Should the player go Super or Fiery, the experience is slower but perhaps intended. Clearing enemies and obstacles makes the screens accelerate near their ends. If the player goes Super or Fiery and ensures they keep as many sprites on screen at once, the game slows further to allow greater precision in platforming on that screen. The safety net of not being Small Mario makes these two options the most lackadaisical. On the other hand, Small Mario makes the game run, if not fast, at least at a consistently higher speed. Jumps thereby become tighter, and Mario much more vulnerable. Clearing enemies and obstacles makes the screens accelerate near their ends, so a bold player can take their chances and double down on them to proceed as quickly as possible. On paper this is perhaps a meaningless choice, but in practice there arises a genuine balancing act of choosing whether or not to bother with power-ups, with clearing enemies, with going fast. By the end of my playthrough, I consistently stayed as Small Mario and threw caution to the wind, making for a tense but rewarding experience.

The (re-)introduction of enemies from Donkey Kong and Mario Bros. are icing on an absurd cake, their inclusion an anachronistic anomaly that presents just enough of a shift in player approach to be meaningful. Sidesteppers may serve an identical purpose to Spinies, but Fighterflies' hops, barrels' rolling, fireballs' outright immunity, and the imminent hazard of icicles all carve out niches of their own without being out of place.

Separately, every facet of Super Mario Bros. Special fails to cut the mustard. As a synthesis, it is remarkable. My victory genuinely felt like it had been hard won from some overwhelming force. The Geiger–Müller counter buzzing was a constant companion I grew fond of. The words of Princess Peach rang clear and true: "You cleared every world. You are the greatest player. Congraturations!" [sic]

I would never recommend anyone play Super Mario Bros. Special without the most open of minds, and even then I think most will get their fill by the time they clear World 1. Maybe I'm too sick in the head to interpret this as a 'bad' game. Maybe I'm to sick to see it as anything but amazing. Either way, its eight worlds sought to chew me up and spit me out. Instead, I prevailed.

This is not a Super Mario Bros. Special as the actual name suggests. The title screen and box make the true meaning subtly known. This is a Super Special Mario Bros. game.

[April Fools' 2023]

Subject: RE: RE: RE: RE: Need another smut review for next month

Date: 2023-03-31T10:52:00

To: Detchibe <detchibe@backloggd.com>

_______________________________________________

Hey, sorry this ended up being so close to your deadline, but I've gone ahead and made some edits to make it harder for people to know you had someone who knows what AI can do cook this up for you in ChatGPT. btw, you should really start looking into tiktoks or something to figure out how to do this yourself but that's none of my business.

The edited copy is below, deletions are striked through, changes/additions are italicised. Sorry it all sounded so much like Tim Rogers, I guess when you tell ChatGPT to write something in the style of someone else, it leans really hard into it. Just make sure to DELETE THE MARKUP THIS TIME lol

_______________________________________________

HELLO! Furthermore,And welcome back to gaming video games!

Once upon a time, in a world where pixelsreigned supreme ruled and the scent smell of CRT monitors filled permeated the air, a game emerged was released that revelled gleefully celebrated its own irreverence self-referentiality and cheeky humor sly wit. That game, my friends, was none other than Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards was the game, my fellow gamers. To quote the inimitable Tim Rogers, "it's like a game that is so perfectly of its time, it's almost from the future." So, l Let me take you on a journey an excursion through this offbeat adventure as we explore into the world of Larry Laffer and his quest search for love in a game that is so wonderfully of its time, it's nearly from the future, as described by the inimitable Tim Rogers.

Developed by Al Lowe and published by Sierra On-Line in 1987, Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards is a point-and-click adventure game created by Al Lowe and released by Sierra On-Line in 1987 that revels takes great pride in its own naughtiness. You assume In this game, you play the role part of Larry Laffer, a balding, 40-year-old virgin, who is clad in a white polyester leisure suit, on a quest to lose his virginity in the seedy underbelly of the fictional city of Lost Wages, clad in a white polyester leisure suit.

The game's graphical interface, a product of its time, is a throwback to the era, with all chunky pixels and vibrant bright colo*urs , which somehow that manage to capture recreate the essence spirit of the late '80s with startling accuracy. uncanny precision. It's like a neon-soaked dream, the visual equivalent of an infectious synth-pop earworm tune that you can't help but dance to won't leave your head.

In my opinion, the best part of Leisure Suit Larry isT the writing , my dear friends, is where Leisure Suit Larry truly shines. Every aspect of the game is infused with Al Lowe's sardonic caustic wit and penchant love for double entendres permeate every corner of the game. The humor is unapologetically bawdy jokes are crude and obscene, like a digital vaudeville routine that leaves no innuendo unturned. It's as if the game is daring you to laugh, while simultaneously winking at its own absurdity knows how ridiculous it is and dares you to laugh at it.

Navigating Enjoyable blunders and unlikely triumphs await Larry as he makes his way through Lost Wages is a delightful exercise in fumbling through failures and improbable successes. There's a certain pleasure in guiding It's amusing to watch our hapless protagonist get put through a series of increasingly bizarre encounters more uncomfortable situations each more cringe-worthy than the last. It's a game that demands of patience and persistence, rewarding the player with a cascade of laughs and groans in equal measure providing equal parts laughter and frustration to its victor.

Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards is not without its flawsn't perfect. The game's notorious copy protection system, designed to thwart the efforts of would-be software pirates, is a cumbersome relic clumsy holdover from of a bygone era. Additionally, t The game's save system can also be unforgiving harsh, requiring frequent backtracking forcing players to repeatedly restart from earlier points in the face event of sudden and unexpected demise.

But d Despite these shortcomings its flaws, Leisure Suit Larry remains is nevertheless a singular experience, a testament to the potential of video games as a medium for humour and storytelling. It's a window glimpse back into a time the days when games were unafraid to take risks more daring, to push the boundaries of taste and propriety in the pursuit of laughter when creators weren't afraid to cross the line between funny and offensive.

A joyful, irreverent romp that invites the player to let go of inhibitions and embrace the absurd,To borrow a phrase from Tim Rogers, Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards is, in the words of Tim Rogers* "a game that is so wonderfully bad, it's absolutely good." It's a delightful, irreverent romp that beckons the player to abandon their inhibitions and embrace the absurd. If you can appreciate its cheeky charm and don't mind its dated mechanics, then Leisure Suit Larry is a journey worth taking.

Subject: RE: RE: RE: RE: Need another smut review for next month

Date: 2023-03-31T10:52:00

To: Detchibe <detchibe@backloggd.com>

_______________________________________________

Hey, sorry this ended up being so close to your deadline, but I've gone ahead and made some edits to make it harder for people to know you had someone who knows what AI can do cook this up for you in ChatGPT. btw, you should really start looking into tiktoks or something to figure out how to do this yourself but that's none of my business.

The edited copy is below, deletions are striked through, changes/additions are italicised. Sorry it all sounded so much like Tim Rogers, I guess when you tell ChatGPT to write something in the style of someone else, it leans really hard into it. Just make sure to DELETE THE MARKUP THIS TIME lol

_______________________________________________

HELLO! Furthermore,

Once upon a time, in a world where pixels

The game's graphical interface

In my opinion, the best part of Leisure Suit Larry is

Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards is

A joyful, irreverent romp that invites the player to let go of inhibitions and embrace the absurd,

I am not so ignorant as to sweep Blizzard's malpractices under the rug for the sake of my own enjoyment. Even ignoring the well-known laundry list of human-facing controversies in recent years, their products have dwindled in appeal to me for over a decade. As lamented in my retrospective on Wrath of the Lich King, much of the core identity of World of Warcraft has languished as it is torn apart at the seams by its players, and haphazardly sewn back together with every expansion. My favourite part of Overwatch was quickly dismantled in favour of supposed balance, a Sisyphean treadmill. Hearthstone crumbles under the weight of its power creep and enormity of knowledge required. Heroes of the Storm was left to wither on the vine. And Diablo III dropped from the heavens with a wet thud. So imagine my shock when Reaper of Souls rose from its ashes like a phoenix that hasn't gone out for over nine years now.

My love of World of Warcraft in particular was two-faced until the release of Shadowlands, the nail in the coffin for any fondness I still had for Azeroth. After completing the core expansion, I deleted Battle.net and never again felt the urge to revisit my account.

But Diablo III continued to call to me. And in a moment of weakness, finally bursting through my mental dam with the early access period for Diablo IV I caved, and felt and feel horrible for it. My scruples, irrelevant! Nothing has ever come close to the specific gameplay of Diablo III, and Diablo IV's beta suggests nothing ever will, not even Blizzard's own offerings.

What I adore about Diablo III is exactly what, arguably, makes it a bad ARPG. The combat is largely meaningless. Everything is item driven rather than character dependent. Builds are largely prescribed and difficult to tweak. There is next to no consequence outside of playing on Hardcore (which I have always exclusively done). Adventure Mode and its bounties are so linear it might as well occur in a hallway. Enemies might as well all be the same. Bosses have no interesting mechanics in end-game scenarios. Legendaries inundate the player to the point where you stop even picking them up. The grinding for Primal Ancients is absurd.

I love it all!

Diablo III is a constant that has been with me for over a decade, through good and bad. I have always known I could return to it for a few days or a week, click things, have them explode, and revel in its own chaos. My characters' deaths rarely bother me, if anything they instill in me a drive to do it all over again. Take bigger risks with my build to get back to speed. Try new gear sets with radically different modes of play (even if the end result is always one-shotting everything even on Torment XVI). In an era of games which try for balance above all else, Diablo III has leaned entirely into the fact that a game of its sort is unable to be balanced. Each Season amps up the absurdity of some small factor, showering the player in loot or damage numbers or some other quirk that widens my eyes. And this latest go around, Season 28, has taken this to what must be a maximal realisation. The new altar destroys any remaining shreds of balance and gets the player as close as possible to basically using a trainer.

I adore it, and I truly missed it. My time with the season is probably at an end, but I will likely return. If not for the next one, then some other season down the line. I'll shake my head the whole time then, just as I did now, so everyone knows I disagree.

My love of World of Warcraft in particular was two-faced until the release of Shadowlands, the nail in the coffin for any fondness I still had for Azeroth. After completing the core expansion, I deleted Battle.net and never again felt the urge to revisit my account.

But Diablo III continued to call to me. And in a moment of weakness, finally bursting through my mental dam with the early access period for Diablo IV I caved, and felt and feel horrible for it. My scruples, irrelevant! Nothing has ever come close to the specific gameplay of Diablo III, and Diablo IV's beta suggests nothing ever will, not even Blizzard's own offerings.

What I adore about Diablo III is exactly what, arguably, makes it a bad ARPG. The combat is largely meaningless. Everything is item driven rather than character dependent. Builds are largely prescribed and difficult to tweak. There is next to no consequence outside of playing on Hardcore (which I have always exclusively done). Adventure Mode and its bounties are so linear it might as well occur in a hallway. Enemies might as well all be the same. Bosses have no interesting mechanics in end-game scenarios. Legendaries inundate the player to the point where you stop even picking them up. The grinding for Primal Ancients is absurd.

I love it all!

Diablo III is a constant that has been with me for over a decade, through good and bad. I have always known I could return to it for a few days or a week, click things, have them explode, and revel in its own chaos. My characters' deaths rarely bother me, if anything they instill in me a drive to do it all over again. Take bigger risks with my build to get back to speed. Try new gear sets with radically different modes of play (even if the end result is always one-shotting everything even on Torment XVI). In an era of games which try for balance above all else, Diablo III has leaned entirely into the fact that a game of its sort is unable to be balanced. Each Season amps up the absurdity of some small factor, showering the player in loot or damage numbers or some other quirk that widens my eyes. And this latest go around, Season 28, has taken this to what must be a maximal realisation. The new altar destroys any remaining shreds of balance and gets the player as close as possible to basically using a trainer.

I adore it, and I truly missed it. My time with the season is probably at an end, but I will likely return. If not for the next one, then some other season down the line. I'll shake my head the whole time then, just as I did now, so everyone knows I disagree.

2022

If the last half-decade has demonstrated anything, it is that the terminally online rhetoric of post-ironic who-gives-a-shit is metastasising. Vine was a benign growth, TikTok a malignant tumour. The netizen-hive-mind-collective that 'solved' the Boston Bombing is directly responsible for the fashwave that is/has/does/will erode democracy. Your grandpa has FOMO and bought $GME to 💎🙌 to the moon and we're all gonna make it, gm, gn, and you're buying into my shitcoin so I can rugpull you because Blizzard nerfed Siphon Life during Obamna's first term. Video games and anime used to be so much better before this forced diversity bullshit ᴡʜᴀᴛ ᴛʜᴇ ꜰᴜᴄᴋ ᴀʀᴇ yᴏᴜ ꜱᴀyɪɴɢ ᴅᴏ yᴏᴜ ʜᴇᴀʀ ᴛʜᴇ ꜱʜɪᴛ ᴅʀɪʙʙʟɪɴɢ ᴏᴜᴛ ᴏꜰ yᴏᴜʀ ᴍᴏᴜᴛʜ yᴏᴜ ᴄʀᴇᴛɪɴ took away the possibility of me getting a tradwife with Abigail Shapiro's body and Marin Kitagawa's face while I [REDACTED] to Angela White after a month of semen retention and get those GAIN$$$$ because there's always a bigger fool and it sure as fuck isn't me and you just don't get this new meme and I'm being gangstalked and I haven't [As the owner of a LandNFT, you own your individual Metalverse patch and secure a permanently assigned place on the Met---

The Milennials are the new Boomers [GEN-X ERASURE] and even the Zoomers are coming of age and they've been inundated with information and bullshit bullshit bullshit so they're casting a mirror back at this fucked up world we've made for them in their own art but some people are trying to be cute and coy with it and you get a YIIK or a Neon Whitebut at least one of those was a good game even if it was still corpo-white-washed faux-sthetics. And your cute and coy attempts and being quirky fail to represent how angry you should be that you were born into this mess of a world because don't you know anger results in nothing? Why yes my favourite podcasts are My Brother, My Brother & Me, and The Adventure Zone, I love to choke down the fetid slurry that is the McElroys' toxic positivity of no bummers and horses and you're being force fed advertisements for fast food and you can't even open your eyes to realise it.

So when a game has the moxie to be viscerally angry, I have to take notice because that feels so genuine in the hyperrealistic world we inhabit. And Splatter is mad that the Internet has made us manipulative, lonely, nostalgic, deluded, greedy, and ultimately willing to harm others (or ourselves) for some gain, be it financial or spiritual or egotistical or chemical. This works where other games borne of the online mindset falter because this runs deep. Rat King Collective didn't disconnect to craft up some malformed half-simulacra that is outdated before it comes out. They never stopped being online, they didn't go for the here and now, they struck at the core of fourteen-year-old-me's identity. This isn't the cream of the crap, this is the dregs of a multitude of online cultures that you, yes, had to be there for. Or maybe you didn't. Does it matter? This goes deep enough that a missed referential quip refuses a reading of "oh this is one of those internet things I don't get," it simply recedes into the background, a cacophony of noise.

It isn't as if the gameplay is some marvel though. It's a spongy xoomer-shooter affair with hand guns and a Dark Souls Borne Ring dodge and commitment to the bit. A leaping enemy is gonna leap! Your dodge isn't going to give you i-frames but it'll get you out of the way and into a new harm's way. I'm not here for the gameplay anyways, it's a means to an end.

This is the video game equivalent of B.R. Yeager's Amygdalatropolis and I ravenously ate it up. Get mad. Wreck shit. Tear it all down. WORLD IS A FUCK

The Milennials are the new Boomers [GEN-X ERASURE] and even the Zoomers are coming of age and they've been inundated with information and bullshit bullshit bullshit so they're casting a mirror back at this fucked up world we've made for them in their own art but some people are trying to be cute and coy with it and you get a YIIK or a Neon White

So when a game has the moxie to be viscerally angry, I have to take notice because that feels so genuine in the hyperrealistic world we inhabit. And Splatter is mad that the Internet has made us manipulative, lonely, nostalgic, deluded, greedy, and ultimately willing to harm others (or ourselves) for some gain, be it financial or spiritual or egotistical or chemical. This works where other games borne of the online mindset falter because this runs deep. Rat King Collective didn't disconnect to craft up some malformed half-simulacra that is outdated before it comes out. They never stopped being online, they didn't go for the here and now, they struck at the core of fourteen-year-old-me's identity. This isn't the cream of the crap, this is the dregs of a multitude of online cultures that you, yes, had to be there for. Or maybe you didn't. Does it matter? This goes deep enough that a missed referential quip refuses a reading of "oh this is one of those internet things I don't get," it simply recedes into the background, a cacophony of noise.

It isn't as if the gameplay is some marvel though. It's a spongy xoomer-shooter affair with hand guns and a Dark Souls Borne Ring dodge and commitment to the bit. A leaping enemy is gonna leap! Your dodge isn't going to give you i-frames but it'll get you out of the way and into a new harm's way. I'm not here for the gameplay anyways, it's a means to an end.

This is the video game equivalent of B.R. Yeager's Amygdalatropolis and I ravenously ate it up. Get mad. Wreck shit. Tear it all down. WORLD IS A FUCK

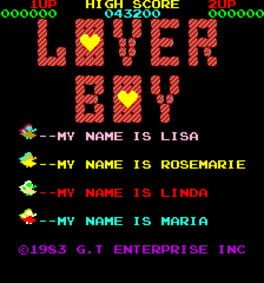

1983

This review is a sister piece to my review of 177. I recommend reading that first.

CW: Sexual assault. The four-letter ‘R-word’ is invoked repeatedly without censoring or obfuscation.

WHEN YOU CATCH A GIRL YOU MUST FIND RIGHT TIMING FOR MAXIMUM RESULT WHICH WILL BE SHOWN ON LOVE METER ACTION OF LOVE MAKING IS BY PUSH BUTTON. BEST TIMING WILL PRODUCE MOST ECSTATIC RESULTS ON FEMALE METER.

Lover Boy is functionally unremarkable, seemingly of as much import as Min Corp.’s Gumbo or Toaplan’s Pipi & Bibi’s. Unlike those games, however, Lover Boy is mired in obscurity, controversy, and a historiography that crumbles under scrutiny.

The gameplay is in line with other maze games of the early 1980s. The Lover Boy chases Lisa, Rosemarie, Linda, and Maria through a labyrinth while police officers and dogs track him. There are item pickups for points, and bottles of perfume which incense Lover Boy, boosting his speed dramatically. All the while, a rendition of the nursery rhyme しょうじょうじのたぬきばやし 「 Shoujouji no Tanukibayashi」 plays merrily. Getting near the girls causes them to run away while yelling HELP, touching them starts your digital assault. Like 177, the player tries to get their victim’s pleasure meter to top out before Lover Boy climaxes. Though 177 used directional inputs, Lover Boy simply has you tapping the button at a steady rhythm. Filling the LADY LOVE to the heart at the top has the women elate Oh~. Climaxing before she can has her yelling NO! and escaping, Lover Boy needing to chase her down again.

Though less explicitly stated in Lover Boy as compared to 177, we see the same rape myth being perpetuated, that of rape becoming a consensual sexual act should the victim reach orgasm. Since Lover Boy is an arcade game, designed to munch the yen of the aroused, there is no good ending to speak of here. The cycle continues in perpetuity until Lover Boy is put behind bars for good. This might suggest an inevitability to the rapist being caught and punished accordingly in due time, but the lives system inadvertently paints a picture wherein a sexual criminal is released and allowed to repeat their crimes with minimal repercussion. Lest we forget the harrowing injustice presented in 177’s manual, “even if he was prosecuted then, he would not be charged with a crime.” Capture is thus an inconvenience, nothing more.

In trying to find out more about Lover Boy, I came to find out it was cause for debate in the Deutscher Bundestag a year after its release. On March 26, 1984, parliamentary spokespersons for Die Grünen (The Greens) Marieluise Beck, Petra Kelly, and Otto Schily brought to the attention of the federal government the installation of light-gun games and Lover Boy in an arcade in Soest. Both were cited as potential violations of Section 131 of the Strafgesetzbuch (Criminal Code), stating therein the illegality of representations which glorified violence. Increasingly realistic depictions of humans as targets for violence, both physical and sexual, necessitated a re-evaluation of existing legislation which made no such effort to criminalise imagery which ‘violated human dignity.’

Sixteen days later, the Federal Government answered the concerns of Die Grünen. The government had come to understand Lover Boy was installed in locations besides Soest, with the understanding that the PCB had been presented by an Italian importer in 1983 at Internationalen Fachmesse für Unterhaltungs- und Warenautomaten (The International Trade Fair for Amusement and Vending Machines) in Frankfurt. The specific board in Soest which drew initial concerns was sourced from a distributor in Dortmund. A March 1984 arcade game trade journal advertised Lover Boy as suitable for children, and thirty-two machines ended up being sold in North Rhine-Westphalia alone, and it came to be understood that Automaten-Selbstkontrolle (ASK) had been presented with incomplete information by which to rate its content; the content was egregious enough to exclude Lover Boy from any rating, leading to the existing machines being purchased and destroyed. A draft law was proposed to the Bundestag, stipulating that games of a violent sort must be prohibited from public areas frequented by children, and postulating that perhaps violent games should be banned wholesale in Germany.

A year later, in April 1985, Section 131 of the Strafgeseztbuch was amended to prohibit representations of violence, rather than just those which glorified it. Additionally, depictions of the ‘violation of human dignity’ were criminalised as well. The ASK became a permanent institution, officially regulating an industry that had, up to that point, been self-regulated.

The ban in Germany is easy to trace, but time and again, it is stated in other reviews and retrospectives that Lover Boy was banned globally outside of Japan with zero evidence offered to support that claim. Searches for “Lover Boy” and “Global Corporation Tokyo” in the United States Congressional Record, Historical Debates of the Parliament of Canada, British Cabinet Papers, CommonLii, Italian Senate record, New York Times, Globe & Mail, all turned up nothing. The German Wikipedia page also makes no mention of Lover Boy being banned anywhere outside of Germany.

Outside of the Bundestag record, some of the only other concrete information about Lover Boy is that it was brought to market by the same company that made 1983’s JoinEm, a non-erotic maze game, released under the name Global Corporation. The pinout and DIP switch documentation included with the Lover Boy PCB had Lover Boy handwritten on them. Weirding the situation further, a seeming bootleg of Lover Boy was released in Spain under the name Triki Triki, changing the developer name to DDT Enterprise, editing the copyright date to 1993.-nicht-jugendfrei-und-nicht-in-Mame/page10) The trail ends there.

If I were to posit a guess, the majority of the inaccurate claims about Lover Boy stem from a single GameFAQs review by defunct user ‘TheSAMMIES’. They claim, erroneously, that Lover Boy:

- Deals with aspects of rape beyond the penetrative act

- Has been banned globally

- Has better gameplay than 177

- Is slang for a man who lures underage women into prostitution (the term is only used in that manner in Dutch)

- Depicts only underage women

- Displays female genitalia

- Has only one maze

- Is of dark comedic value

None of that is true whatsoever. Their spurious falsehoods are on display in their review of 177 as well, claiming falsely:

- 177 is the police code for rape (it is simply the section of the Japanese Criminal Code which criminalises rape)

- RapeLay tackles rape more tactfully

- 177’s rape scenes show plant life and the night sky (they actually occur in a black void)

- Has controls in its rape scenes for getting onto Kotoe, penetrating her, building up sexual stamina (you actually just gyrate, the graphics barely animating)

- That 177 received a remake called 171 wherein Hideo is replaced by a squid monster, Kotoe by a maid (I have found no evidence of such a game existing)

Whether these ideas are being born purely from their mind, some misinterpretation of the realities of history, or whatever else, this individual seems to have irreparably tarnished the known history of Lover Boy, leading to prolonged repetition of the same incorrect claims. If there were any evidence to back up those ideas, wouldn’t they have shown themselves? Does it matter? Nobody cares about this game, nobody knows about it, can we fault the few who have documented it for their inaccuracies?

Yes, because it makes determining the truth all the harder. Yes, because it puts the onus of honestly on those who come after the fact. Yes, because just as these games are harmful in their depictions, speaking of them falsely is just as much of a disservice to history.

CW: Sexual assault. The four-letter ‘R-word’ is invoked repeatedly without censoring or obfuscation.

WHEN YOU CATCH A GIRL YOU MUST FIND RIGHT TIMING FOR MAXIMUM RESULT WHICH WILL BE SHOWN ON LOVE METER ACTION OF LOVE MAKING IS BY PUSH BUTTON. BEST TIMING WILL PRODUCE MOST ECSTATIC RESULTS ON FEMALE METER.

Lover Boy is functionally unremarkable, seemingly of as much import as Min Corp.’s Gumbo or Toaplan’s Pipi & Bibi’s. Unlike those games, however, Lover Boy is mired in obscurity, controversy, and a historiography that crumbles under scrutiny.

The gameplay is in line with other maze games of the early 1980s. The Lover Boy chases Lisa, Rosemarie, Linda, and Maria through a labyrinth while police officers and dogs track him. There are item pickups for points, and bottles of perfume which incense Lover Boy, boosting his speed dramatically. All the while, a rendition of the nursery rhyme しょうじょうじのたぬきばやし 「 Shoujouji no Tanukibayashi」 plays merrily. Getting near the girls causes them to run away while yelling HELP, touching them starts your digital assault. Like 177, the player tries to get their victim’s pleasure meter to top out before Lover Boy climaxes. Though 177 used directional inputs, Lover Boy simply has you tapping the button at a steady rhythm. Filling the LADY LOVE to the heart at the top has the women elate Oh~. Climaxing before she can has her yelling NO! and escaping, Lover Boy needing to chase her down again.

Though less explicitly stated in Lover Boy as compared to 177, we see the same rape myth being perpetuated, that of rape becoming a consensual sexual act should the victim reach orgasm. Since Lover Boy is an arcade game, designed to munch the yen of the aroused, there is no good ending to speak of here. The cycle continues in perpetuity until Lover Boy is put behind bars for good. This might suggest an inevitability to the rapist being caught and punished accordingly in due time, but the lives system inadvertently paints a picture wherein a sexual criminal is released and allowed to repeat their crimes with minimal repercussion. Lest we forget the harrowing injustice presented in 177’s manual, “even if he was prosecuted then, he would not be charged with a crime.” Capture is thus an inconvenience, nothing more.

In trying to find out more about Lover Boy, I came to find out it was cause for debate in the Deutscher Bundestag a year after its release. On March 26, 1984, parliamentary spokespersons for Die Grünen (The Greens) Marieluise Beck, Petra Kelly, and Otto Schily brought to the attention of the federal government the installation of light-gun games and Lover Boy in an arcade in Soest. Both were cited as potential violations of Section 131 of the Strafgesetzbuch (Criminal Code), stating therein the illegality of representations which glorified violence. Increasingly realistic depictions of humans as targets for violence, both physical and sexual, necessitated a re-evaluation of existing legislation which made no such effort to criminalise imagery which ‘violated human dignity.’

Sixteen days later, the Federal Government answered the concerns of Die Grünen. The government had come to understand Lover Boy was installed in locations besides Soest, with the understanding that the PCB had been presented by an Italian importer in 1983 at Internationalen Fachmesse für Unterhaltungs- und Warenautomaten (The International Trade Fair for Amusement and Vending Machines) in Frankfurt. The specific board in Soest which drew initial concerns was sourced from a distributor in Dortmund. A March 1984 arcade game trade journal advertised Lover Boy as suitable for children, and thirty-two machines ended up being sold in North Rhine-Westphalia alone, and it came to be understood that Automaten-Selbstkontrolle (ASK) had been presented with incomplete information by which to rate its content; the content was egregious enough to exclude Lover Boy from any rating, leading to the existing machines being purchased and destroyed. A draft law was proposed to the Bundestag, stipulating that games of a violent sort must be prohibited from public areas frequented by children, and postulating that perhaps violent games should be banned wholesale in Germany.

A year later, in April 1985, Section 131 of the Strafgeseztbuch was amended to prohibit representations of violence, rather than just those which glorified it. Additionally, depictions of the ‘violation of human dignity’ were criminalised as well. The ASK became a permanent institution, officially regulating an industry that had, up to that point, been self-regulated.

The ban in Germany is easy to trace, but time and again, it is stated in other reviews and retrospectives that Lover Boy was banned globally outside of Japan with zero evidence offered to support that claim. Searches for “Lover Boy” and “Global Corporation Tokyo” in the United States Congressional Record, Historical Debates of the Parliament of Canada, British Cabinet Papers, CommonLii, Italian Senate record, New York Times, Globe & Mail, all turned up nothing. The German Wikipedia page also makes no mention of Lover Boy being banned anywhere outside of Germany.

Outside of the Bundestag record, some of the only other concrete information about Lover Boy is that it was brought to market by the same company that made 1983’s JoinEm, a non-erotic maze game, released under the name Global Corporation. The pinout and DIP switch documentation included with the Lover Boy PCB had Lover Boy handwritten on them. Weirding the situation further, a seeming bootleg of Lover Boy was released in Spain under the name Triki Triki, changing the developer name to DDT Enterprise, editing the copyright date to 1993.-nicht-jugendfrei-und-nicht-in-Mame/page10) The trail ends there.

If I were to posit a guess, the majority of the inaccurate claims about Lover Boy stem from a single GameFAQs review by defunct user ‘TheSAMMIES’. They claim, erroneously, that Lover Boy:

- Deals with aspects of rape beyond the penetrative act

- Has been banned globally

- Has better gameplay than 177

- Is slang for a man who lures underage women into prostitution (the term is only used in that manner in Dutch)

- Depicts only underage women

- Displays female genitalia

- Has only one maze

- Is of dark comedic value

None of that is true whatsoever. Their spurious falsehoods are on display in their review of 177 as well, claiming falsely:

- 177 is the police code for rape (it is simply the section of the Japanese Criminal Code which criminalises rape)

- RapeLay tackles rape more tactfully

- 177’s rape scenes show plant life and the night sky (they actually occur in a black void)

- Has controls in its rape scenes for getting onto Kotoe, penetrating her, building up sexual stamina (you actually just gyrate, the graphics barely animating)

- That 177 received a remake called 171 wherein Hideo is replaced by a squid monster, Kotoe by a maid (I have found no evidence of such a game existing)

Whether these ideas are being born purely from their mind, some misinterpretation of the realities of history, or whatever else, this individual seems to have irreparably tarnished the known history of Lover Boy, leading to prolonged repetition of the same incorrect claims. If there were any evidence to back up those ideas, wouldn’t they have shown themselves? Does it matter? Nobody cares about this game, nobody knows about it, can we fault the few who have documented it for their inaccuracies?

Yes, because it makes determining the truth all the harder. Yes, because it puts the onus of honestly on those who come after the fact. Yes, because just as these games are harmful in their depictions, speaking of them falsely is just as much of a disservice to history.

2023

Cute, short, and snap-snap-snappy with a utilisation of the crank that sets it apart from other crank-heavy titles like Crankin's Time Travel Adventure and A Balanced Brew. Whereas those games go for a one-to-oneness between physical movement and gameplay, Direct Drive brings momentum into the picture, leading to a looser style of play. This works stupendously in theory, but the low resistance of the crank, and relatively slow cranking involved, means what should feel like pedalling a bike or grinding coffee beans instead seems unresponsive at times. With generous room for error, however, that never becomes a problem prohibiting progress. Even the managers' requests and harsher timing penalties never make this frustrating or, frankly, challenging. I got three stars on every song on my first try, and only the singular diversion of calibrating the turntable gave me any difficulty.

But you know what? That's fine. I don't use my Playdate to feel frustrated, I use it as a short(er) diversion, a little amuse-bouche of what games can achieve. Purely as a game, Direct Drive could use improving. As a concept, it's great, and it put a smile on my face which is what I want from this little yellow doodad.

But you know what? That's fine. I don't use my Playdate to feel frustrated, I use it as a short(er) diversion, a little amuse-bouche of what games can achieve. Purely as a game, Direct Drive could use improving. As a concept, it's great, and it put a smile on my face which is what I want from this little yellow doodad.

Sweet as sugar.

Sweet as young love.

Sweet as can be.

Nostalgic and enraptured with youth as Norwegian Wood.

Magical and intertwined as Kafka on the Shore.

Two blurred lines proceeding apace in parallel as 1Q84.

Perfectly self contained within its own narrative.

Abound with the peculiarities of children.

Spare and sparse.

Father's guidance.

Mother's embrace.

One's own destiny.

Comfortable.

Joyful.

Warm.

Sweet as young love.

Sweet as can be.

Nostalgic and enraptured with youth as Norwegian Wood.

Magical and intertwined as Kafka on the Shore.

Two blurred lines proceeding apace in parallel as 1Q84.

Perfectly self contained within its own narrative.

Abound with the peculiarities of children.

Spare and sparse.

Father's guidance.

Mother's embrace.

One's own destiny.

Comfortable.

Joyful.

Warm.

2007

While a DS port of the PS2 original was certain to be a mixed bag, it's still amazing how much this version of the game drops the ball. Every obstacle is dealt with by Cookie stepping on a button, and Cream doing an action on the touch screen or via the microphone. This leads to prolonged periods of Cookie standing still and having an enemy come after him to steal your time. Segmenting the game in this way would be fine, but without anything for Cookie to reasonably do, the player is left pacing awkwardly with one hand, tapping away with the other.

Either due to hardware limitations or its nature as a portable or because of the touchscreen implementation, levels are also much shorter and less dense than on PS2. There are fewer enemies and obstacles meaning many levels end before arriving at their meatiest parts. The Adventures of Cookie & Cream wasn't some exemplar of kishoutenketsu design like a modern Mario title, but there was still room for mechanics to flourish and interact more meaningfully than they can here.

Cookie & Cream never feels like the synthesis that the title implies, its two halves becoming as disparate as a tub of chocolate ice cream and one of vanilla placed next to each other in the freezer. Sure, they're together, but they have no bearing on each other. Even if it would betray some of the DS's appeal to get rid of the touchscreen functionality, a system closer to the PS2's single-player would work wonders, the left controls moving Cookie, the right, Cream. They could even have them remain on separate screens, perhaps eschew the big orange buttons and bring back the tangible object interaction? Or maybe I'm barking up the wrong tree, complaining about the single-player in a game meant for pairs, and I should just eat my deconstructed Oreos with a forced smile.

Either due to hardware limitations or its nature as a portable or because of the touchscreen implementation, levels are also much shorter and less dense than on PS2. There are fewer enemies and obstacles meaning many levels end before arriving at their meatiest parts. The Adventures of Cookie & Cream wasn't some exemplar of kishoutenketsu design like a modern Mario title, but there was still room for mechanics to flourish and interact more meaningfully than they can here.

Cookie & Cream never feels like the synthesis that the title implies, its two halves becoming as disparate as a tub of chocolate ice cream and one of vanilla placed next to each other in the freezer. Sure, they're together, but they have no bearing on each other. Even if it would betray some of the DS's appeal to get rid of the touchscreen functionality, a system closer to the PS2's single-player would work wonders, the left controls moving Cookie, the right, Cream. They could even have them remain on separate screens, perhaps eschew the big orange buttons and bring back the tangible object interaction? Or maybe I'm barking up the wrong tree, complaining about the single-player in a game meant for pairs, and I should just eat my deconstructed Oreos with a forced smile.

2016

Unequivocally the best video game ever made, though that has to be cheating, right? After all, you wouldn’t say your Raspberry Pi loaded with ROMs is itself a video game. An official compilation already stretches the definition of a video game, much to the chagrin of any dweeb trying to weasel their way out of providing an actual list of their favourite games. Yet this unofficial potpourri does what a mere compilation cannot, what your ROM library fails at. Multibowl! puts these games on equal footing with one another, contextualises them, renders their objectives concrete, and synthesises them into a new, greater whole. It is the wet dream of the games historian, the archivist, the obscura-seeker, the high-score-chaser, the competitive gamer, the informed, the ignorant, and the creative.

Bennett Foddy and AP Thomson have unenviably plumbed the depths of numerous ROM sets to scrounge up treasures both noteworthy and forgotten, presenting them all as equals as games and micro-competitive arenas. Obvious mainstays of games history, Mario Bros., Gauntlet, Metal Slug, and NBA Jam operate as immediately recognisable artefacts with goals and control schema that are already familiar to many. However, they are just as likely to come up as titles which are not generally considered competitive and oppositional: Lemmings; Maze; Bonanza Bros. Though lacking internal mechanisms for confrontational gameplay, clever use of save states and memory analysis allow Multibowl! to check for some change in some variable to grant one player a point.

One of the greatest joys in Multibowl! is its deep cuts, its pulling up of games you have never heard of, the sort of title your eye skips over in your search for that SegaSonic Bros. ROM, titles bordering on the uncanny in their near-familiarity, games that make you quickly jot down their title out of befuddlement or glee. Games you would never reasonably play. In a vacuum of playing them on their own, those works might not hold your attention long enough to grasp their purpose or gameplay. Within the rapid pace of Multibowl!, within a framework of having no choice, they demand attention, dissection, and comprehension. The coercion for the players to stick with these titles for a mere thirty seconds acts as a microexposure to the realities of most of games history, namely the lack of anything else to do. When these games necessarily compete for your attention in backlogs and ROM sets with hundreds, if not thousands, of games, there is no reason for most players to approach an understanding of them. Why expose myself to the dregs of history when Pac-Man is right there?

A games historian, archivist, or obscura-seeker has some secondary goal for their play here, that of context and exposure. Someone like myself is not necessarily playing these for their worth as fun experiences, but to come away with a fuller understanding of games as a whole, games as a cultural expression, games as a reflection of a zeitgeist, games as escapism, games as political tools, games as violence, games as transgression, games as collaborative, games as competitive, games as more than just games. Games as a means, not an end.

Multibowl!’s real purpose is not as a game, at least not to me, but as some smörgåsbord of curatorial excellence, diversity, and inversion. It demonstrates how games have always been inventive and worthy of attention in some capacity, while still remaining semi-boundless in and of itself, conveying the unceasing work of history. Histories are forever rewritten for new contexts. The once irrelevant becomes critically important with changing tides. The once foundational becomes a historiographical assumption. With vast shifts in the goals of games histories, there will always be more to uncover, more to connect.

Here's to 1,000 more.

Bennett Foddy and AP Thomson have unenviably plumbed the depths of numerous ROM sets to scrounge up treasures both noteworthy and forgotten, presenting them all as equals as games and micro-competitive arenas. Obvious mainstays of games history, Mario Bros., Gauntlet, Metal Slug, and NBA Jam operate as immediately recognisable artefacts with goals and control schema that are already familiar to many. However, they are just as likely to come up as titles which are not generally considered competitive and oppositional: Lemmings; Maze; Bonanza Bros. Though lacking internal mechanisms for confrontational gameplay, clever use of save states and memory analysis allow Multibowl! to check for some change in some variable to grant one player a point.

One of the greatest joys in Multibowl! is its deep cuts, its pulling up of games you have never heard of, the sort of title your eye skips over in your search for that SegaSonic Bros. ROM, titles bordering on the uncanny in their near-familiarity, games that make you quickly jot down their title out of befuddlement or glee. Games you would never reasonably play. In a vacuum of playing them on their own, those works might not hold your attention long enough to grasp their purpose or gameplay. Within the rapid pace of Multibowl!, within a framework of having no choice, they demand attention, dissection, and comprehension. The coercion for the players to stick with these titles for a mere thirty seconds acts as a microexposure to the realities of most of games history, namely the lack of anything else to do. When these games necessarily compete for your attention in backlogs and ROM sets with hundreds, if not thousands, of games, there is no reason for most players to approach an understanding of them. Why expose myself to the dregs of history when Pac-Man is right there?

A games historian, archivist, or obscura-seeker has some secondary goal for their play here, that of context and exposure. Someone like myself is not necessarily playing these for their worth as fun experiences, but to come away with a fuller understanding of games as a whole, games as a cultural expression, games as a reflection of a zeitgeist, games as escapism, games as political tools, games as violence, games as transgression, games as collaborative, games as competitive, games as more than just games. Games as a means, not an end.

Multibowl!’s real purpose is not as a game, at least not to me, but as some smörgåsbord of curatorial excellence, diversity, and inversion. It demonstrates how games have always been inventive and worthy of attention in some capacity, while still remaining semi-boundless in and of itself, conveying the unceasing work of history. Histories are forever rewritten for new contexts. The once irrelevant becomes critically important with changing tides. The once foundational becomes a historiographical assumption. With vast shifts in the goals of games histories, there will always be more to uncover, more to connect.

Here's to 1,000 more.

1994

Speaking strictly on 'Around the World,' the game portion of 3D Atlas, this is horrifically weak. The information presented in its trivia questions can be gleaned from the main program's statistics and multimedia videos. For every vexillological vexation there comes a quandary about orchid imports for three periphery states. Be asked to identify a country from its capital, then identify another from a collage. It is altogether boring at best. Points are converted to miles, and every three questions you trade in your miles to select a destination in your quest to circumnavigate the globe. Efficient travel relies on deeper geographic knowledge, but outside multiplayer (which I didn't even know the 3DO supported) it hardly matters.

Where 3D Atlas shines is as an early multimedia font of encyclopedic knowledge. Physically manipulating the globe is not the topic of interest, but the supplementary videos, renders, and tools. Abound in 3D Atlas is Marshall McLuhan's notion of the global village, making the planet metaphorically smaller through easy access to international knowledge and peoples. Though this often presents itself here, as elsewhere, in the exacerbation of differences between the Western world and that of the Other, that global-mindedness was a reality throughout the 1990s. It is thereby unapologetic in its effective appropriation of signifiers of the Other, believing this uncritical presentation to be more egalitarian and human-focused. That is all to say, those depictions in 3D Atlas are, at best, anthropologically and ethnographically disingenuous, at worst, a reinforcement of prejudice. By way of example, Afghanistan's country profile speaks only of colonialism and the nation's global position as a centre of conflict. Panama's touches on Manuel Noriega, political turmoil, and the Panama Canal. Former Soviet states might have a sentence devoted to pre-modern histories, but would convince the unaware 'player' that Soviet history constitutes their totality. The image for each country is a postcard typically comprised of traditional garb, a natural feature, and a cultural construct.