psychbomb

BACKER

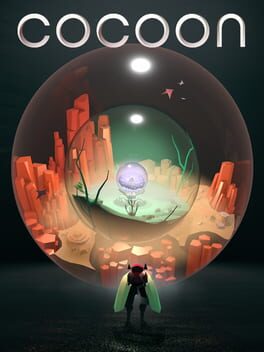

Cocoon 2023

Log Status

Completed

Playing

Backlog

Wishlist

Rating

Time Played

--

Days in Journal

1 day

Last played

October 12, 2023

Platforms Played

Not yet a butterfly.

A while back, I wrote a review for Resident Evil 2’s remake, and I gave it five stars. Part of the justification I gave at the time was that I couldn’t think of “anything that I disliked about it”, and I’m beginning to suspect that may have been the wrong way of looking at it. Not only does it frame the praise in a pretty backhanded way, but it’s not wholly accurate to why it got the score that it did, either. To be fair to myself, I knew at the time that it was an oversimplification that I wrote down purely for the sake of having something snappy to say about the game, but it’s games like Cocoon that make me rethink taking that position. Like Resident Evil 2, I can’t think of anything I disliked about Cocoon. Why, then, does the former get five stars, and the latter get three?

Unrealized potential.

There are a lot of pieces of art and a lot of places and a lot of people out there in the world which aren’t unlikable, but they aren’t especially likeable, either. It’s not enough to not have anything that’s unlikable about you. You need to have something more that draws people in and keeps them there. For some, I imagine the art direction of Cocoon alone is going to be enough to fill in the gaps of the weak puzzle design and a premature ending — it almost was, for me — and that’s good. But I’m left wanting for more in a way that didn’t satisfy me, because Cocoon's got a lot of promise that it can't quite deliver on.

The core gimmick of hopping between universes has been done dozens of times before, but Cocoon stands out in how seamless the transitions are. There’s a very, very lengthy pre-load when you first boot the game up as it assembles all of the assets, and this allows you to completely avoid loading screens; whatever loading is going on after you start the game is completely unnoticeable, which is a definite achievement for something that looks this visually impressive. The game has an immensely strong identity, with all of its insect-like machines and swelling synth arpeggios; equally impressive is the paring down of the control scheme to a single analog stick and one button. You would expect your verbs to be fairly limited when you've only got a single button for interacting with the world, but it allows you to carry orbs, drag objects, run through motion sensors, activate platforms, teleport to different worlds, control grub-like drones, and shoot energy blasts. There are a lot of moving parts to keep track of, and that suggests there's going to be some very in-depth puzzle design.

What’s unfortunate, then, is how all of these actions being contextual means that you’ll very rarely be using them in tandem with one another to solve problems. Most of the puzzles are little more than identifying which orb you need to be carrying at a given time, carrying that orb until the puzzle is solved, and then swapping out for a different orb as needed until you can progress to the next area. The dimension-hopping aspect itself actually ends up taking something of a backseat as you move further and further through the game; progressing through each of the orb’s sub-worlds will eventually place you in a spot that you can’t get out of, locking you to a single screen within that orb. The red orb that you start the game with, for example, will leave you stuck in about thirty square feet of space you can walk around in for the last hour of the game, meaning that it devolves into only being usable as a sort of backpack to store other orbs inside of. The white orb’s world similarly gets pared down to purely being a place to store the red orb inside of, and the purple orb’s world might actually just be one or two screens. Even the final puzzle of the game that requires you to nest all of the orbs inside one another in a specific order is painfully easy due to how linear of a solution it is, reflecting a lot of the other puzzles in the game; the hardest part of most of these is when you know what you need to do, but it’ll take you a couple minutes to walk around setting it all up.

I've struggled with the rest of this review because I walked away from writing for a few days, and now that I'm back at it, I barely remember anything about Cocoon. There are these vague vignette flashes, where I can recall a setpiece or two — the tennis match against the big orb guardian, the drone puzzles — but the rest of these color-coded worlds bleed into one another as a brown-grey muck. What I definitely didn't expect out of Cocoon was for as much of it to be as forgettable as it ultimately feels, but I doubt I'll be able to recall much of anything about it by this time next week. With the puzzles being as linear as they are, the game relies heavily on being a sightseeing tour, and it feels sort of like I drove straight through it. It's the type of game that I want to like a lot more than I actually do. What's here could have been a lot more impressive than it is, but it isn't, and that makes it hurt worse than if it had no potential at all.

You can't only do nothing wrong.

A while back, I wrote a review for Resident Evil 2’s remake, and I gave it five stars. Part of the justification I gave at the time was that I couldn’t think of “anything that I disliked about it”, and I’m beginning to suspect that may have been the wrong way of looking at it. Not only does it frame the praise in a pretty backhanded way, but it’s not wholly accurate to why it got the score that it did, either. To be fair to myself, I knew at the time that it was an oversimplification that I wrote down purely for the sake of having something snappy to say about the game, but it’s games like Cocoon that make me rethink taking that position. Like Resident Evil 2, I can’t think of anything I disliked about Cocoon. Why, then, does the former get five stars, and the latter get three?

Unrealized potential.

There are a lot of pieces of art and a lot of places and a lot of people out there in the world which aren’t unlikable, but they aren’t especially likeable, either. It’s not enough to not have anything that’s unlikable about you. You need to have something more that draws people in and keeps them there. For some, I imagine the art direction of Cocoon alone is going to be enough to fill in the gaps of the weak puzzle design and a premature ending — it almost was, for me — and that’s good. But I’m left wanting for more in a way that didn’t satisfy me, because Cocoon's got a lot of promise that it can't quite deliver on.

The core gimmick of hopping between universes has been done dozens of times before, but Cocoon stands out in how seamless the transitions are. There’s a very, very lengthy pre-load when you first boot the game up as it assembles all of the assets, and this allows you to completely avoid loading screens; whatever loading is going on after you start the game is completely unnoticeable, which is a definite achievement for something that looks this visually impressive. The game has an immensely strong identity, with all of its insect-like machines and swelling synth arpeggios; equally impressive is the paring down of the control scheme to a single analog stick and one button. You would expect your verbs to be fairly limited when you've only got a single button for interacting with the world, but it allows you to carry orbs, drag objects, run through motion sensors, activate platforms, teleport to different worlds, control grub-like drones, and shoot energy blasts. There are a lot of moving parts to keep track of, and that suggests there's going to be some very in-depth puzzle design.

What’s unfortunate, then, is how all of these actions being contextual means that you’ll very rarely be using them in tandem with one another to solve problems. Most of the puzzles are little more than identifying which orb you need to be carrying at a given time, carrying that orb until the puzzle is solved, and then swapping out for a different orb as needed until you can progress to the next area. The dimension-hopping aspect itself actually ends up taking something of a backseat as you move further and further through the game; progressing through each of the orb’s sub-worlds will eventually place you in a spot that you can’t get out of, locking you to a single screen within that orb. The red orb that you start the game with, for example, will leave you stuck in about thirty square feet of space you can walk around in for the last hour of the game, meaning that it devolves into only being usable as a sort of backpack to store other orbs inside of. The white orb’s world similarly gets pared down to purely being a place to store the red orb inside of, and the purple orb’s world might actually just be one or two screens. Even the final puzzle of the game that requires you to nest all of the orbs inside one another in a specific order is painfully easy due to how linear of a solution it is, reflecting a lot of the other puzzles in the game; the hardest part of most of these is when you know what you need to do, but it’ll take you a couple minutes to walk around setting it all up.

I've struggled with the rest of this review because I walked away from writing for a few days, and now that I'm back at it, I barely remember anything about Cocoon. There are these vague vignette flashes, where I can recall a setpiece or two — the tennis match against the big orb guardian, the drone puzzles — but the rest of these color-coded worlds bleed into one another as a brown-grey muck. What I definitely didn't expect out of Cocoon was for as much of it to be as forgettable as it ultimately feels, but I doubt I'll be able to recall much of anything about it by this time next week. With the puzzles being as linear as they are, the game relies heavily on being a sightseeing tour, and it feels sort of like I drove straight through it. It's the type of game that I want to like a lot more than I actually do. What's here could have been a lot more impressive than it is, but it isn't, and that makes it hurt worse than if it had no potential at all.

You can't only do nothing wrong.