I have this good friend whose taste in games seems to be constantly crawling backwards in time. From the PlayStation 1 to old arcade cabinets, to the Atari 2600, and now to this primitive little text delight. Of course, I'm grateful - I don't exactly stay on the bleeding edge of the gaming scene but at the same time my feet are pretty firmly planted in the contemporary indie game community, itch.io and all that and it's nice to get some perspective from the past especially when I've on some level been yearning to really give it a chance.

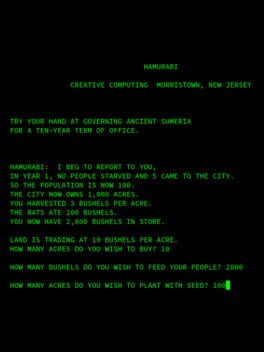

Hamurabi is a quaint little resource management game that despite its incredibly simple gameplay loop and primitive representation and programming manages to be an engaging bite-sized game the whole way through. In this game, you are Hamurabi, the ruler of some unknown land. Every year you are to divvy out the crops between being food for the people, being currency for acquiring and selling your land, and being planted for future harvests. The objective of the game is technically to have as much land as you can by the start of year 11, ignoring population and bushel count, but the consolidation of every single in-game transaction to heavily involve bushels in some way allows for every year of action to be a heavily considered and decisive move towards your goal. The short factor of the game helps this too, it's just long enough where you can really get the ball rolling but also short enough that if you are to catastrophically mess up it's no real skin off your back.

By year 5 of my first playthrough I had derived all of the non-random code that the game relies upon - it's all pretty simple math - but even when I had these things figured out and I had a calculator and notepad by my side jotting down random formulas and conversions, it was just as fun in this mode of play as it was kind of winging it. This takes the prize for the oldest game I've played, and manages to be surprisingly robust despite any apprehensions you might have about playing a game that was made before your parents were probably born.

Hamurabi is a quaint little resource management game that despite its incredibly simple gameplay loop and primitive representation and programming manages to be an engaging bite-sized game the whole way through. In this game, you are Hamurabi, the ruler of some unknown land. Every year you are to divvy out the crops between being food for the people, being currency for acquiring and selling your land, and being planted for future harvests. The objective of the game is technically to have as much land as you can by the start of year 11, ignoring population and bushel count, but the consolidation of every single in-game transaction to heavily involve bushels in some way allows for every year of action to be a heavily considered and decisive move towards your goal. The short factor of the game helps this too, it's just long enough where you can really get the ball rolling but also short enough that if you are to catastrophically mess up it's no real skin off your back.

By year 5 of my first playthrough I had derived all of the non-random code that the game relies upon - it's all pretty simple math - but even when I had these things figured out and I had a calculator and notepad by my side jotting down random formulas and conversions, it was just as fun in this mode of play as it was kind of winging it. This takes the prize for the oldest game I've played, and manages to be surprisingly robust despite any apprehensions you might have about playing a game that was made before your parents were probably born.

Hamurabi como conhecemos é o port caseiro e comercial de um jogo de mainframe criado por um hacker-acadêmico para demonstrar as capacidades do PDP8, que, por sua vez, é a versão simplificada de um jogo ainda mais antigo conhecido como The Sumerian Game, financiado por um projeto governamental e criado para ser usado como ferramenta didática em sala de aula. Em cada passo dessa transição, de um ambiente escolar para acadêmico para comercial, o jogo foi tendo não apenas parte de seu design original subtraída como também sua filosofia completamente modificada. Acho que vale a pena fazer uma pequena retrospectiva sobre esse processo.

O Sumerian Game é considerado um jogo perdido. Seu código não foi preservado de forma alguma, o projeto que o financiou se extinguiu em 1967 e as pessoas chave no desenvolvimento do game (a professora e game designer Mabel Addis e o programador William McKay) faleceram anos atrás. As únicas fontes de informação que temos sobre o game vêm de alguns escaneamentos digitais preservados pelo Strong Museum of Play e o relatório final do projeto que financiou o game, detalhando sua produção, uso e resultados. O relatório é uma fonte especialmente valiosa devido a quantidade de detalhes que tem sobre o funcionamento do game, servindo não-intencionalmente como uma mistura de Game Design Document e Post-Mortem.

Com a documentação que nos resta, é possível tirar algumas conclusões importantes sobre o caráter do Sumerian Game. Primeiro, antes de ser um game, ele era uma ferramenta pedagógica. Seu fator lúdico era um meio para um fim - neste caso, ensinar crianças do fundamental alguns princípios básicos de economia. Mas diferente de peças de edutainment de hoje em dia, o Sumerian Game não foi pensado como algo a ser usado fora da escola, para que crianças aprendessem enquanto brincavam sozinhas. O jogo foi feito para ser usado dentro de sala de aula, com o papel ativo dos professores no processo da educação não sendo deixado de lado, e sendo integrado com outras ferramentas de educação como slides e aulas gravadas. O fato da game designer ser uma professora experiente fica bem claro nisso.

Um segundo ponto a se tocar é que o Sumerian Game não carecia de recursos. Ele tinha acesso irrestrito a um dos hardwares mais poderosos de sua época, o IBM 1401, e o projeto foi financiado pelo próprio Department of Education dos EUA, angariando o equivalente a quase 1 milhão de dólares em dinheiros atuais segundo a Wikipédia.

Uma conclusão que se tem ao juntarmos esses dois pontos é que preocupações econômicas eram praticamente inexistentes a criação e desenvolvimento desse game, algo um tanto que peculiar na mídia ludoeletrônica. Apesar de eu não compartilhar da visão (um tanto cínica, imo) que o caráter comercial de 99% dos games os impede de atingir o estatuto de "arte de verdade", é inegável que as preocupações comerciais afetam sim a forma e conteúdo das obras de uma maneira ou outra - às vezes de forma catastrófica, vide microtransações e a Web 3.0. Não aqui: The Sumerian Game estava numa posição privilegiada que parece só ter existido nesse breve momento da pré-história gamer em que os jogos eram quase exclusivamente projetos governamentais ou acadêmicos.

Que fique claro, só porque o Sumerian Game não tinha a intenção (ou sequer a condição) de eventualmente se tornar um produto comercial não quer dizer que estava imune à estrutura capitalista subjacente da sociedade que o criou. Mas aqui essa superestrutura não se manifesta como um elemento da commoditização da arte, e sim de formas ao mesmo tempo mais sutis e mais profundas, ouso dizer que até mesmo filosóficas. Essas manifestações ficam dolorosamente explícitas se lermos o relatório final que linkei mais cedo. Apesar do jogo ser ambientado na antiga suméria e de um de seus objetivos declarados ser ensinar aos alunos o funcionamento daquela sociedade, todas as representações da economia antiga são reflexos de conceitos contemporâneos, especificamente liberais, da economia. Toda a dinâmica social é explicada em termos de Labor e Capital, dois conceitos completamente alheios às mentalidades das sociedades daquela época e lugar e completamente anacrônicos dentro desse contexto. De fato o Sumerian Game foi criado para ensinar princípios econômicos modernos, não história antiga, mas isso não dá ao game um passe livre para massacra a História: o relatório final deixa bem claro que a escolha dos sumérios foi para "protestar contra a crescente tendência em currículos escolares de ignorar civilizações pré-Gregas". Um sentimento do qual eu compartilho totalmente, mas que o jogo falhou em aproveitar em sua execução.

Dito isto, as realidades da "estrutura capitalista subjacente" deixariam de ter efeitos limitados à conceitualizações equivocadas e anacronismos acidentais quando a transição do Sumerian Game para Hamurabi terminasse. O primeiro passo desse processo foi a recriação do jogo original agora num ambiente empresarial-acadêmico, não mais escolar, inicialmente sob o nome The Summer Game. Doug Dymet, empregado da Digital Equipment Corporation, considerou o conceito do game apropriado e interessante o suficiente para demonstrar as capacidades da linguagem de programação FOCAL) e o poder do DEC PDP-8, os novo e lustrosos produtos de seus empregadores. The Summer Game, portanto, é uma tech-demo, uma demonstração do que um sistema PDP-8 mínimo era capaz de fazer. A preocupação não era mais ensinar economia ou história, e sim deslumbrar e impressionar os usuários - possivelmente, mesmo que não explicitamente, sob o pretexto de justificar um investimento na máquina.

Além de ter perdido sua função pedagógica, o Summer Game também perdeu parte de sua liberdade de recursos. O PDP-8 não era uma mainframe que ocupava uma sala inteira que nem o IBM 1401, nem Doug Dymet financiado pelo Department of Education para fazer o jogo. Então, por motivos técnicos e não-técnicos, o Summer Game simplificou muita coisa do Sumerian Game. Enquanto a versão original era dividida em três fases, com mecânicas de desenvolvimento tecnológico, rotas de comércio e guerras sendo adicionadas com o decorrer do tempo, o Summer Game se foca exclusivamente no que corresponde à primeira fase do Sumerian Game: distribua X alqueires de trigo para alimentar sua população e determine quantos acres de terra serão plantados.

Que o jogo fosse condensado e simplificado na transição de uma plataforma para a outra é compreensível. Não obstante, ao investigarmos o que foi simplificado ou ignorado e o que foi preservado ou adicionado. Por que Dymet escolheu reconstruir a primeira parte do game, focada no gerenciamento de recursos finitos, e não na segunda ou terceira partes, em que as relações com outras cidades-estado e outras dinâmicas sociais internas (desenvolvimentos tecnológicos, comércio) são postas em evidência? Se me permitem teorizar um pouquinho, a razão deve ter sido simplesmente porque Dymet considerou a primeira parte do game a mais interessante. Nela temos uma relação bem explícita entre as escolhas e consequências do jogador: alimente seu povo direito e ele crescerá e sua sociedade crescerá; faça decisões equivocadas e o povo morrerá.

Chegamos então ao último passo da transição, quando David H. Ahl portou o Summer Game da linguagem FOCAL para a muito mais popular e, criticamente, difundida BASIC. Foi então que o game assumiu de vez o nome Hamurabi. A tradução para o BASIC permitiu que o game fosse comercializado: em 1973 Ahl publicaria este e vários outros pequenos jogos na revista 101 BASIC Games, uma das primeiras revistas de computação a vender um milhão de cópias.

É importante notar aqui a forma essa forma particular de como Hamurabi enfim virou um produto comercial e atingisse um público muito mais amplo. Em vez de disquetes ou outro tipo de mídia de armazenamento digital, uma das formas mais comuns de distribuição de software dos 70 e início dos 80 era na forma de revistas e catálogos que vinham com o código de pequenos jogos e programas impressos em suas páginas para o usuário redigitar e rodar em casa. Em grande parte (exclusivamente?), esses programas estavam escritos em BASIC, que servia como uma espécie de língua franca entre os computadores da época e permitia rodar programas numa variedade gigantesca de hardware com poucas ou nenhuma modificação. Hamurabi e diversos outros games que foram criados em mainframes de ambientes empresariais e acadêmicos teriam ficados confinados a um pequeno grupinho de hackers e dificilmente teriam a influência que têm hoje não fosse a linguagem de programação BASIC e a distribuição de software em revistas e catálogos.

Uma consequência disso tudo é que para se experimentar Hamurabi de uma forma convincente, como ele foi experimentado pela maioria das pessoas dos 70 e 80, exige que o jogador pegue uma dessas revistas e redigite o código impresso linha por linha no computador, para então rodar num interpretador e rezar para não ter colocado algum vírgula ou sinal errado em algum lugar. Essa expectativa de que o usuário vai ler, redigitar, rodar e talvez debugar o código do jogo manualmente acaba criando algumas limitações, já que um jogo muito complexo ou com código muito grande seria inviável de se distribuir nesse modelo. Portanto, ao fim de várias transformações, a experiência de The Sumerian Game foi condensada, simplificada e destilada ao máximo, preservando apenas as partes que fossem consideradas chamativas o bastante, essenciais o suficiente, razoáveis de se replicar nos hardwares/linguagens alvo e minimamente commoditizáveis. Este é Hamurabi.

O Sumerian Game é considerado um jogo perdido. Seu código não foi preservado de forma alguma, o projeto que o financiou se extinguiu em 1967 e as pessoas chave no desenvolvimento do game (a professora e game designer Mabel Addis e o programador William McKay) faleceram anos atrás. As únicas fontes de informação que temos sobre o game vêm de alguns escaneamentos digitais preservados pelo Strong Museum of Play e o relatório final do projeto que financiou o game, detalhando sua produção, uso e resultados. O relatório é uma fonte especialmente valiosa devido a quantidade de detalhes que tem sobre o funcionamento do game, servindo não-intencionalmente como uma mistura de Game Design Document e Post-Mortem.

Com a documentação que nos resta, é possível tirar algumas conclusões importantes sobre o caráter do Sumerian Game. Primeiro, antes de ser um game, ele era uma ferramenta pedagógica. Seu fator lúdico era um meio para um fim - neste caso, ensinar crianças do fundamental alguns princípios básicos de economia. Mas diferente de peças de edutainment de hoje em dia, o Sumerian Game não foi pensado como algo a ser usado fora da escola, para que crianças aprendessem enquanto brincavam sozinhas. O jogo foi feito para ser usado dentro de sala de aula, com o papel ativo dos professores no processo da educação não sendo deixado de lado, e sendo integrado com outras ferramentas de educação como slides e aulas gravadas. O fato da game designer ser uma professora experiente fica bem claro nisso.

Um segundo ponto a se tocar é que o Sumerian Game não carecia de recursos. Ele tinha acesso irrestrito a um dos hardwares mais poderosos de sua época, o IBM 1401, e o projeto foi financiado pelo próprio Department of Education dos EUA, angariando o equivalente a quase 1 milhão de dólares em dinheiros atuais segundo a Wikipédia.

Uma conclusão que se tem ao juntarmos esses dois pontos é que preocupações econômicas eram praticamente inexistentes a criação e desenvolvimento desse game, algo um tanto que peculiar na mídia ludoeletrônica. Apesar de eu não compartilhar da visão (um tanto cínica, imo) que o caráter comercial de 99% dos games os impede de atingir o estatuto de "arte de verdade", é inegável que as preocupações comerciais afetam sim a forma e conteúdo das obras de uma maneira ou outra - às vezes de forma catastrófica, vide microtransações e a Web 3.0. Não aqui: The Sumerian Game estava numa posição privilegiada que parece só ter existido nesse breve momento da pré-história gamer em que os jogos eram quase exclusivamente projetos governamentais ou acadêmicos.

Que fique claro, só porque o Sumerian Game não tinha a intenção (ou sequer a condição) de eventualmente se tornar um produto comercial não quer dizer que estava imune à estrutura capitalista subjacente da sociedade que o criou. Mas aqui essa superestrutura não se manifesta como um elemento da commoditização da arte, e sim de formas ao mesmo tempo mais sutis e mais profundas, ouso dizer que até mesmo filosóficas. Essas manifestações ficam dolorosamente explícitas se lermos o relatório final que linkei mais cedo. Apesar do jogo ser ambientado na antiga suméria e de um de seus objetivos declarados ser ensinar aos alunos o funcionamento daquela sociedade, todas as representações da economia antiga são reflexos de conceitos contemporâneos, especificamente liberais, da economia. Toda a dinâmica social é explicada em termos de Labor e Capital, dois conceitos completamente alheios às mentalidades das sociedades daquela época e lugar e completamente anacrônicos dentro desse contexto. De fato o Sumerian Game foi criado para ensinar princípios econômicos modernos, não história antiga, mas isso não dá ao game um passe livre para massacra a História: o relatório final deixa bem claro que a escolha dos sumérios foi para "protestar contra a crescente tendência em currículos escolares de ignorar civilizações pré-Gregas". Um sentimento do qual eu compartilho totalmente, mas que o jogo falhou em aproveitar em sua execução.

Dito isto, as realidades da "estrutura capitalista subjacente" deixariam de ter efeitos limitados à conceitualizações equivocadas e anacronismos acidentais quando a transição do Sumerian Game para Hamurabi terminasse. O primeiro passo desse processo foi a recriação do jogo original agora num ambiente empresarial-acadêmico, não mais escolar, inicialmente sob o nome The Summer Game. Doug Dymet, empregado da Digital Equipment Corporation, considerou o conceito do game apropriado e interessante o suficiente para demonstrar as capacidades da linguagem de programação FOCAL) e o poder do DEC PDP-8, os novo e lustrosos produtos de seus empregadores. The Summer Game, portanto, é uma tech-demo, uma demonstração do que um sistema PDP-8 mínimo era capaz de fazer. A preocupação não era mais ensinar economia ou história, e sim deslumbrar e impressionar os usuários - possivelmente, mesmo que não explicitamente, sob o pretexto de justificar um investimento na máquina.

Além de ter perdido sua função pedagógica, o Summer Game também perdeu parte de sua liberdade de recursos. O PDP-8 não era uma mainframe que ocupava uma sala inteira que nem o IBM 1401, nem Doug Dymet financiado pelo Department of Education para fazer o jogo. Então, por motivos técnicos e não-técnicos, o Summer Game simplificou muita coisa do Sumerian Game. Enquanto a versão original era dividida em três fases, com mecânicas de desenvolvimento tecnológico, rotas de comércio e guerras sendo adicionadas com o decorrer do tempo, o Summer Game se foca exclusivamente no que corresponde à primeira fase do Sumerian Game: distribua X alqueires de trigo para alimentar sua população e determine quantos acres de terra serão plantados.

Que o jogo fosse condensado e simplificado na transição de uma plataforma para a outra é compreensível. Não obstante, ao investigarmos o que foi simplificado ou ignorado e o que foi preservado ou adicionado. Por que Dymet escolheu reconstruir a primeira parte do game, focada no gerenciamento de recursos finitos, e não na segunda ou terceira partes, em que as relações com outras cidades-estado e outras dinâmicas sociais internas (desenvolvimentos tecnológicos, comércio) são postas em evidência? Se me permitem teorizar um pouquinho, a razão deve ter sido simplesmente porque Dymet considerou a primeira parte do game a mais interessante. Nela temos uma relação bem explícita entre as escolhas e consequências do jogador: alimente seu povo direito e ele crescerá e sua sociedade crescerá; faça decisões equivocadas e o povo morrerá.

Chegamos então ao último passo da transição, quando David H. Ahl portou o Summer Game da linguagem FOCAL para a muito mais popular e, criticamente, difundida BASIC. Foi então que o game assumiu de vez o nome Hamurabi. A tradução para o BASIC permitiu que o game fosse comercializado: em 1973 Ahl publicaria este e vários outros pequenos jogos na revista 101 BASIC Games, uma das primeiras revistas de computação a vender um milhão de cópias.

É importante notar aqui a forma essa forma particular de como Hamurabi enfim virou um produto comercial e atingisse um público muito mais amplo. Em vez de disquetes ou outro tipo de mídia de armazenamento digital, uma das formas mais comuns de distribuição de software dos 70 e início dos 80 era na forma de revistas e catálogos que vinham com o código de pequenos jogos e programas impressos em suas páginas para o usuário redigitar e rodar em casa. Em grande parte (exclusivamente?), esses programas estavam escritos em BASIC, que servia como uma espécie de língua franca entre os computadores da época e permitia rodar programas numa variedade gigantesca de hardware com poucas ou nenhuma modificação. Hamurabi e diversos outros games que foram criados em mainframes de ambientes empresariais e acadêmicos teriam ficados confinados a um pequeno grupinho de hackers e dificilmente teriam a influência que têm hoje não fosse a linguagem de programação BASIC e a distribuição de software em revistas e catálogos.

Uma consequência disso tudo é que para se experimentar Hamurabi de uma forma convincente, como ele foi experimentado pela maioria das pessoas dos 70 e 80, exige que o jogador pegue uma dessas revistas e redigite o código impresso linha por linha no computador, para então rodar num interpretador e rezar para não ter colocado algum vírgula ou sinal errado em algum lugar. Essa expectativa de que o usuário vai ler, redigitar, rodar e talvez debugar o código do jogo manualmente acaba criando algumas limitações, já que um jogo muito complexo ou com código muito grande seria inviável de se distribuir nesse modelo. Portanto, ao fim de várias transformações, a experiência de The Sumerian Game foi condensada, simplificada e destilada ao máximo, preservando apenas as partes que fossem consideradas chamativas o bastante, essenciais o suficiente, razoáveis de se replicar nos hardwares/linguagens alvo e minimamente commoditizáveis. Este é Hamurabi.

Es muy interesante jugar esto y darte cuenta de que las nociones de esperar, anticipar y esperar resultados en videojuegos se estaban codificando en una computadora de algún campus de Estados Unidos. La versión que jugué procedía del Apple I y era muy difícil de pasar, principalmente porque los números subían y bajaban de forma bastante aleatoria. Pero me obsesioné tanto por conseguir la cantidad correcta de cultivos que acabé poniéndome nervioso tratando de impedir ningún gasto innecesario. Que un programa tan antiguo me pusiera ansioso dice algo sobre el poder que tiene esta cosilla.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

It's very interesting playing this and realizing that notions of waiting, anticipating and expecting things in-game were being codified in a giant computer on some USAn campus somewhere. The version I played came from the Apple I and it was very difficult to beat, mainly because numbers seemed to go up or down based on pure randomness. But I got so invested in getting the right amount of crops for each turn that I became nervous of any expenditure I made within the game. That a game this old made me anxious says something about the power of this little thing.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

It's very interesting playing this and realizing that notions of waiting, anticipating and expecting things in-game were being codified in a giant computer on some USAn campus somewhere. The version I played came from the Apple I and it was very difficult to beat, mainly because numbers seemed to go up or down based on pure randomness. But I got so invested in getting the right amount of crops for each turn that I became nervous of any expenditure I made within the game. That a game this old made me anxious says something about the power of this little thing.

(Content warning: Plague.)

The Sumerian Game [1964-1967]/Hamurabi [1968/1973] [sic], as that dating indicates, has a particularly convoluted and amorphous release history that I’m going to have to spend the first few paragraphs here just walking through. There were more or less three variations by different authors, although I could expand that all the way into the 1980s. The first variation is The Sumerian Game [1964-1967].

---- MUSICAL INTERMISSION: The Michael Yonkers Band – Puppeting [1968]. “Computers do no wrong.” ----

The Sumerian Game is really only comparable to The Oregon Trail [1971/75]. They’re both edutainment games made for a young child’s classroom history module on a mainframe printer-only computer with a rudimentary narrative. (You can see why I initially cut it for redundancy.) By all accounts I know of, The Sumerian Game was the first video game to ever have any explicit narrative scaffolding at all, thanks to female writer, designer, and schoolteacher Mabel Addis. The Sumerian Game wasn’t just its computer code, it was a whole three-act theatrical experience with a 20-minute slideshow that went along with a tape recording that the player would watch before touching the computer, staged only a few times for a few years for a few 9- and 10-year-olds. It wasn’t a product to be packaged, it was a fleeting moment. Today, naturally, it is lost and we can only hear its echoes. It’s another one of those games that survives only through documentation.

The ways that The Oregon Trail and The Sumerian Game survived into the following decades were down two very different routes. The Oregon Trail became a discrete plaything of an increasingly corporate world of video gaming. The Sumerian Game, though initially a collaboration between massive institutions, IBM funded by the US Department Of Education, became instead diffused as essentially public domain, adopted by the “anyone can code” crowd of utopian computer liberators.

That’s where Hamurabi comes in. The 1968 version, called The King Of Sumeria, was designed by Doug Dyment as a tech demo, this time for the programming language FOCAL and on a PDP-8 instead of a PDP-1. He did this entirely based off of having The Sumerian Game verbally described to him — I’m not being in the slightest metaphorical when I talk about games spreading like folk songs in this era. A man named David H. Ahl then ported this game from FOCAL to BASIC, added a couple things, and moreover popularized and distributed the game, from his position first as essentially a computer salesperson for DEC (creators of the PDP series of macrocomputers) then in the 1970s as a magazine-running personal computer evangelist, with two hit books full of BASIC games that you the consumer could type into your own machine to learn to code and have something to do with your new machine, which contained the version of Hamurabi played by most (including myself.)

To me, this whole convoluted chain seems emblematic of the entire pre-lapsarian era of computer gaming that came to a close around 1977 with the home computing boom, not just largely forgotten today but shrouded in the fog of forgetfulness even within itself. We will never see video games under a distribution model anything like this ever again. Most obviously, we are now long beyond the era when it was expected that to use a computer you ought to be able to program, with all the implications on the idea of a fixed product that implies. In the Mainframe Era, computers were often a solution looking for a problem and it was an open question what computer games were even for, and initially many were aimed at some higher utility, such as education, business simulation, military simulation, or simply demonstrating (and thereby selling) computers. Pong [1972] was the future, though: Games came to exist primarily to sell themselves to the consumer, as a discrete and portable unit, whether rented by the quarter or eventually owned outright. They were there to be profitable. And almost the entire idiom of video games, and its focus on entertainment and aesthetic values instead of some utility, evolved from this paradigm. Free games today and in a hypothetical post-capitalist future still exist in the shadow of this legacy, and are often conceptualized as competing in some variety of abstract market anyway.

All the more fascinating then that Hamurabi, a quintessential artifact of this pre-commercial games culture, is literally about projecting and naturalizing modern commercial relations all the way back to the dawn of civilization itself, Ancient Sumeria. The Fertile Crescent has been traditionally regarded as the birthplace of modern economics, with interstate trade to support logistically impressive infrastructure projects, and not just interest and debt but debt jubilees, and an urban class of artisan craftspeople, and careful accounting of stock and ownership with cuneiform. The Sumerian Game had a firmer concern as an educational game with representing actual history and a wider variety of commodities from which more complexity arose. While an alternative 1968 name for Hamurabi is King Of Sumeria and it carelessly slaps the most famous Sumerian in there irrelevant and misspelled, in The Sumerian Game you are a succession of temple priests in a specific city (Lagash) performing middle-management, representing the actual economic structure of Sumeria in finer detail.

The Sumerian Game makes a few noble and active efforts to de-financialize its economy. As the postmortem says twice, one of the key lessons is that “the real cost of anything is what we must sacrifice to get it,” and by this it means that costs are not money but labor and resources and even deaths. One of the key innovations in Ancient Sumeria was its use of silver as a universal unit of exchange, aka money, but silver itself was rarely actually used in transactions, instead it was chiefly for the convenience of bureaucratic accounting. This brought the society probably as close as any historical pre-coinage society to the mythical “barter system” dreamt up by Adam Smith, which is just a money system that inefficiently and inconveniently doesn’t have money but somehow does have some concept of universal quantifiable value and tidy, prompt tit-for-tat exchanges. But The Sumerian Game probably leans too far into barter, especially in the interstate trade phase, because as a computer game, built out of math, it simply cannot express an economy or indeed a world that at some point doesn’t reduce to universal quantifiable value. Hamurabi, conversely, simply does not care about such fine distinctions and dives right in — for its purposes, “bushel” is another word for dollar.

The Sumerian Game took as its model works such as The Carnegie Tech Management Game [1963] or the AMA Top Management Decision Simulator [1955], business simulations. Due mainly to technical limitations, these were themselves rudimentary compared to simulations where more complicated and involved mathematical operations could be performed with pencil, paper, and a person. The advantage it did present was a mimetic, theatrical aspect: presentations with fancy special equipment for a limited time only, an invitation for you the player to act a part that most likely is not available to you in real life, and the computer laundering an illusion of steely objectivity to the proceedings. Accentuating this aspect is probably from whence the narrative scaffolding came.

Hamurabi also has a narrative, one completely original to itself, which is one of its most compelling qualities and one that I’ve never actually seen remarked upon. A game like this, you would expect it to be random. The Sumerian Game is. The Oregon Trail is. But it isn’t. In Hamurabi, the same things happen in the same order every time you play. As in HUTSPIEL [1955], all of the player’s inputs have strictly-deterministic and easily-divined corresponding outputs, with the only variation in outputs coming along fixed and predetermined order. And the order in which these variations are deliberately laid out clearly constitute story beats, but to explain that I have to explain the basics of the gameplay, since it’s a story told with its gameplay.

Every turn, you get a status report on a few numbers: The year (turn number), the number of people who starved, the number of new citizens, the population, acreage, harvest rate, loss of bushels to rats, bushels in storage, and the current asking price of acres. Then, you get three questions: 1) How many acres you’ll buy? (And if none, how many to sell?) 2) How much to feed to the people? and 3) How many acres you’ll seed? All of these prices are expressed in bushels, even though you don’t seed an acre with processed bushels of the harvest. Maybe it’s just payment for labor.

The first part of the game is just figuring out the basic shape of the numbers it’s asking for by guessing. How many bushels does it take to feed one person for one turn? (20.) How many acres can you harvest? (10 times the population then subtract 1.) How many bushels to seed an acre? (1.) If you typed this game’s source code in, you may have just been able to know this going in, but me I can’t read code. If you’re just playing, you repeat the first turn or two turns over and over again to hone in on these figures. This, like The Oregon Trail, is essentially a survival game, where you have resources to manage optimally and if you do poorly, you die. Except instead of dying to the elements or to zombies, you die to popular revolt.

The Prisoner [1980], one of my all-time favorite games, contains a game-within-a-game where the main character gets to pretend to be The Caretaker of their prison. It’s a hard game to win because practically everything you can do smacks the simulated prison irrecoverably out of balance, and then when you fail you are told that maybe now you understand how hard the Caretaker has it. The whole game is satire, and this minigame cuts to the heart of its point about ideological indoctrination. It might have been inspired by Hamurabi, or something else inspired by it at least.

In any case, Hamurabi and by extension The Sumerian Game (remember it?) have the same dynamic. It uses its initial difficulty, survival mechanics of penny-pinching resources immediately underlined with an overpopulation-panic scenario to shake you loose of any idea that farming alone might sustain humanity, to convince you to roleplay, to buy its mimesis, to make you empathize with the position of a managerial ruler, to naturalize it, to explain its logic, make it seem eternal and inescapable. When you win, that is, maximize acreage without the ugly business of doing it at the expense of your population, Hamurabi tells you “Charlemagne, Disraeli, and Jefferson combined could not have done better!” An odd assortment — the famously religious feudal emperor and the secular slavedriver revolutionary republican, with a Victorian imperialist conservative prime minister in the middle as if a bridge. It’s all the same to Hamurabi’s broad strokes. Charlemagne, Disraeli, Jefferson, and the real Hammurabi were all statesmen. They all had to deal with the most fundamental political question of them all: who gets what.

The trick comes once you’ve got those ratios down and can start to intelligently calculate things. (This game begs to be played with a calculator at-hand and maybe some scratch paper.) If you only use the resources at hand at the start of the game, feeding everybody and then feeding them again the next year is unachievable, you’ll find yourself in an unwinnable tailspin right away. Maintaining is not an option. You start the game in the toughest position you’re likely to be in the entire game. You’re on the backfoot, you’re overextended, there’s too many mouths to feed and not enough grain stored up to be a cushion.

There’s only two working solutions that can get you to year 4: First, you can willfully starve the population to death, so long as you don’t kill so many people in one fell swoop that they kill you. This reduces the demand on your supply to a manageable equilibrium where you can reliably feed people by the sweat of their brow, sometimes pulling a surplus when the harvest is very good and sometimes dipping into that surplus when the population rises overmuch from immigration, for the rest of the game. You muddle along from one year to the next and end up at the end either pretty close to where you started if you let off the throttle once you could and stopped throwing like 20 people a year into the engine, or with a comfortable budget surplus if you keep cosigning the population to death year after year. This austerity strategy is both morally hideous and clearly sub-optimal, though.

Second, you can commit to feeding everyone and immediately sell the 200 acres that you don’t even have the capacity to farm. In year 2, not only will you have enough barley to feed all your people and seed everything you have, but also to buy back what you just sold the year prior and then some if you want, not because of a particularly good harvest, but because you now have about two and a half times the liquid capital you started with and the price of land has fallen precipitously this year. Congratulations, you just played the real estate market and won big. You sold high and bought low. This is the winning strategy. With either strategy, you can get through to the end of the game.

As a gameplay arc, this is notable because it’s on-boarding the player by deliberately putting the most difficult circumstances right up front, such that you can’t even see most of the game if you don’t first learn how it works. The concept of on-boarding the player through their staged interactions with the game was, in my experience, really very rare before Super Mario Bros [1985] popularized it. But unlike Super Mario Bros’ gentle tutorial introducing things one by one, Hamurabi has a sink-or-swim attitude afforded by not just its simplicity and ease of quick replay but most importantly its complete transparency. The players don’t need things laid out one by one by the game, they can test things one by one for themselves.

As a story, this is fascinating to me. In this game, the market saves lives, flat out. Market speculation is here not some optional layer entirely alien to the process that produces commodities. Rather, it is forcefully shown to be absolutely central to keeping the social machine running smoothly. Without its financial input juicing it, the system breaks down and people die from poverty, that’s the trade-off this game leads with. What it makes me wonder is: Who are you buying the land from and selling it to? What is this market? There’s a historically-grounded answer, but clearly Hamurabi isn’t fussed about accuracy, and there’s obviously no textual answer either.

Land prices are random, not in the sense that they’re not the same in the same order every time you play, but in the sense that there’s no apparent logical correlation between it and any of the other information that you have, no apparent push and pull of supply and demand. If anything, there’s a vague inverse correlation between years with good harvests and years with low land prices, where you might figure it should be the opposite way around, because your neighbors must have had a good harvest too, thereby demonstrating the fertility and thus value of the land to their owners while also pushing the bids proportionally higher among other buyers who likewise struck it rich this year. Instead of working according to their own independent logic, the convolutions of the market are scripted for the benefit of the player.

This is all to say that the real estate trade, while integral to the system, itself exists outside of the boundaries of the system. Think of the thermodynamics of a natural ecosystem, with grass and a moose. The moose is fueled by the grass, but the grass can’t subsist on moose turd pie alone. It needs the power of our yellow sun, which obviously exists external to whatever happens on our planet, but nevertheless its juice feeding into the system is necessary for its continued operation. If the sun stopped shining one day, things here on Earth would immediately enter a brutal death spiral, where the only way to survive for even a little bit would be to burn up all the already-stored energy that exists within our system and die a little slower. That’s exactly how getting money out of the market works in Hamurabi. Immigration, too, is modeled as input from outside that fuels the inside, and that replenishment of the labor force (oddly the only way your labor force increases at all) is the only thing that keeps the strategy of deliberately starving your own people to death temporarily viable for the 10 years you play through.

Though this is a highly simplified model, real-world capitalism has the same need to feed from outside its own system to sustain itself without cannibalism, hence its endless thirst for expansion into “new” markets, but with the added consideration that in trading, every gain is fundamentally someone else’s loss. On a global scale, there’s no net profit, you’re just moving things around. (There are things that aren’t zero-sum in this capitalist world, but I don’t want to go on for several thousand more words right now, I’m already on a tangent.) Which brings us back to who you’re buying the land from. Whoever they are, they must be operating under the same fundamental constraints as the player. They also need to eat. And your gains are their losses. Eventually, if you’re playing towards the good ending of the game, you will have more land than you can possibly farm with your workforce, just sitting around completely fallow and feeding nobody, because it’s more profitable in arbitrage.

The beginning of the game is not the last crisis your regime faces, just the most severe, especially because you’re not prepared. It deploys further crises with delicacy: for the first 3 years, rats aren’t a problem, but in the 4th year they are a severe problem. However, this is mitigated by it being the best harvest yet in the game, such that it works out to about the same return you got last year. It could maybe catch you out if you somehow got through the first 3 years just by selling acres for food. After that, there’s another 3 years with no incident to recover from crises, though land prices are kinda high for a while. In year 6 they drop back low, real low. Now’s the time to buy! Oh, but it’s just lulling you into a false sense of security… In year 7 the rats strike again, and they bring their friend, a horrible plague! Fully half the population dies!

…We’ve done a lot of thinking about plagues these past couple years, haven’t we? I think this game that’s generally completely derelict on its ancestral educational mandate can still teach us a little something, though. Because the plague killing half the population might sound bad… but from this perspective, the capitalist manager staring at numbers, it’s secretly nothing but a boon. The plague is profit. You even get a second one in year 10 after another break to lick your wounds, which lets you juice your numbers one last time. Remember that deliberately killing your own people is a valid strategy in this game. This moment allows you to taste the benefit of sacrificing the population without having to get your hands dirty. Land prices are way up in year 7, even though if we reasonably assume our neighbors also caught the plague, that means they would suddenly have a lot of excess land that they don’t have the labor force to work, so supply should be up and driving prices way down. But you also suddenly have a lot of excess land you can’t work, on top of the excess land you bought on the cheap last turn. And you can sell every scrap of it for astronomical profit, then buy it back the next year when prices are low.

People don’t matter. They’re not even commodities to this game, they’re just numbers, a mathematical operation that chews up 20 bushels a head a turn, and if you throw another 10 bushels down on top of that for a total of 30 bushels per person, you get between 10 and 50 bushels per head in return. If you consider the 20 non-negotiable, then that 10 looks like a good deal, because it always gets made back at a minimum. But taken as a whole 30… a year with more than a break-even 3 per acre yield is an exceptionally good year. Playing the market is way more profitable. An acre farmed can only yield 5 bushels per acre at maximum, which is nice to accrue as like an interest rate on your portfolio, but an acre bought low and sold high can yield up to 11 bushels per acre. I put the strategies in opposition earlier, but there’s no reason you can’t combine both austerity and speculative trading and kill as many people as you can get away with to cut the cost of supporting their lives whilst trading fallow land back and forth to REALLY maximize your profit at the direct expense of everyone’s well-being.

It’s all an artifact of a hastily-balanced game, a trifling toy really, with no reflection on the real modern systems it’s imitating.

(Originally posted on my blog, [https://arcadeidea.wordpress.com/2022/02/21/hamurabi-1968-1973/](Arcade Idea).)

The Sumerian Game [1964-1967]/Hamurabi [1968/1973] [sic], as that dating indicates, has a particularly convoluted and amorphous release history that I’m going to have to spend the first few paragraphs here just walking through. There were more or less three variations by different authors, although I could expand that all the way into the 1980s. The first variation is The Sumerian Game [1964-1967].

---- MUSICAL INTERMISSION: The Michael Yonkers Band – Puppeting [1968]. “Computers do no wrong.” ----

The Sumerian Game is really only comparable to The Oregon Trail [1971/75]. They’re both edutainment games made for a young child’s classroom history module on a mainframe printer-only computer with a rudimentary narrative. (You can see why I initially cut it for redundancy.) By all accounts I know of, The Sumerian Game was the first video game to ever have any explicit narrative scaffolding at all, thanks to female writer, designer, and schoolteacher Mabel Addis. The Sumerian Game wasn’t just its computer code, it was a whole three-act theatrical experience with a 20-minute slideshow that went along with a tape recording that the player would watch before touching the computer, staged only a few times for a few years for a few 9- and 10-year-olds. It wasn’t a product to be packaged, it was a fleeting moment. Today, naturally, it is lost and we can only hear its echoes. It’s another one of those games that survives only through documentation.

The ways that The Oregon Trail and The Sumerian Game survived into the following decades were down two very different routes. The Oregon Trail became a discrete plaything of an increasingly corporate world of video gaming. The Sumerian Game, though initially a collaboration between massive institutions, IBM funded by the US Department Of Education, became instead diffused as essentially public domain, adopted by the “anyone can code” crowd of utopian computer liberators.

That’s where Hamurabi comes in. The 1968 version, called The King Of Sumeria, was designed by Doug Dyment as a tech demo, this time for the programming language FOCAL and on a PDP-8 instead of a PDP-1. He did this entirely based off of having The Sumerian Game verbally described to him — I’m not being in the slightest metaphorical when I talk about games spreading like folk songs in this era. A man named David H. Ahl then ported this game from FOCAL to BASIC, added a couple things, and moreover popularized and distributed the game, from his position first as essentially a computer salesperson for DEC (creators of the PDP series of macrocomputers) then in the 1970s as a magazine-running personal computer evangelist, with two hit books full of BASIC games that you the consumer could type into your own machine to learn to code and have something to do with your new machine, which contained the version of Hamurabi played by most (including myself.)

To me, this whole convoluted chain seems emblematic of the entire pre-lapsarian era of computer gaming that came to a close around 1977 with the home computing boom, not just largely forgotten today but shrouded in the fog of forgetfulness even within itself. We will never see video games under a distribution model anything like this ever again. Most obviously, we are now long beyond the era when it was expected that to use a computer you ought to be able to program, with all the implications on the idea of a fixed product that implies. In the Mainframe Era, computers were often a solution looking for a problem and it was an open question what computer games were even for, and initially many were aimed at some higher utility, such as education, business simulation, military simulation, or simply demonstrating (and thereby selling) computers. Pong [1972] was the future, though: Games came to exist primarily to sell themselves to the consumer, as a discrete and portable unit, whether rented by the quarter or eventually owned outright. They were there to be profitable. And almost the entire idiom of video games, and its focus on entertainment and aesthetic values instead of some utility, evolved from this paradigm. Free games today and in a hypothetical post-capitalist future still exist in the shadow of this legacy, and are often conceptualized as competing in some variety of abstract market anyway.

All the more fascinating then that Hamurabi, a quintessential artifact of this pre-commercial games culture, is literally about projecting and naturalizing modern commercial relations all the way back to the dawn of civilization itself, Ancient Sumeria. The Fertile Crescent has been traditionally regarded as the birthplace of modern economics, with interstate trade to support logistically impressive infrastructure projects, and not just interest and debt but debt jubilees, and an urban class of artisan craftspeople, and careful accounting of stock and ownership with cuneiform. The Sumerian Game had a firmer concern as an educational game with representing actual history and a wider variety of commodities from which more complexity arose. While an alternative 1968 name for Hamurabi is King Of Sumeria and it carelessly slaps the most famous Sumerian in there irrelevant and misspelled, in The Sumerian Game you are a succession of temple priests in a specific city (Lagash) performing middle-management, representing the actual economic structure of Sumeria in finer detail.

The Sumerian Game makes a few noble and active efforts to de-financialize its economy. As the postmortem says twice, one of the key lessons is that “the real cost of anything is what we must sacrifice to get it,” and by this it means that costs are not money but labor and resources and even deaths. One of the key innovations in Ancient Sumeria was its use of silver as a universal unit of exchange, aka money, but silver itself was rarely actually used in transactions, instead it was chiefly for the convenience of bureaucratic accounting. This brought the society probably as close as any historical pre-coinage society to the mythical “barter system” dreamt up by Adam Smith, which is just a money system that inefficiently and inconveniently doesn’t have money but somehow does have some concept of universal quantifiable value and tidy, prompt tit-for-tat exchanges. But The Sumerian Game probably leans too far into barter, especially in the interstate trade phase, because as a computer game, built out of math, it simply cannot express an economy or indeed a world that at some point doesn’t reduce to universal quantifiable value. Hamurabi, conversely, simply does not care about such fine distinctions and dives right in — for its purposes, “bushel” is another word for dollar.

The Sumerian Game took as its model works such as The Carnegie Tech Management Game [1963] or the AMA Top Management Decision Simulator [1955], business simulations. Due mainly to technical limitations, these were themselves rudimentary compared to simulations where more complicated and involved mathematical operations could be performed with pencil, paper, and a person. The advantage it did present was a mimetic, theatrical aspect: presentations with fancy special equipment for a limited time only, an invitation for you the player to act a part that most likely is not available to you in real life, and the computer laundering an illusion of steely objectivity to the proceedings. Accentuating this aspect is probably from whence the narrative scaffolding came.

Hamurabi also has a narrative, one completely original to itself, which is one of its most compelling qualities and one that I’ve never actually seen remarked upon. A game like this, you would expect it to be random. The Sumerian Game is. The Oregon Trail is. But it isn’t. In Hamurabi, the same things happen in the same order every time you play. As in HUTSPIEL [1955], all of the player’s inputs have strictly-deterministic and easily-divined corresponding outputs, with the only variation in outputs coming along fixed and predetermined order. And the order in which these variations are deliberately laid out clearly constitute story beats, but to explain that I have to explain the basics of the gameplay, since it’s a story told with its gameplay.

Every turn, you get a status report on a few numbers: The year (turn number), the number of people who starved, the number of new citizens, the population, acreage, harvest rate, loss of bushels to rats, bushels in storage, and the current asking price of acres. Then, you get three questions: 1) How many acres you’ll buy? (And if none, how many to sell?) 2) How much to feed to the people? and 3) How many acres you’ll seed? All of these prices are expressed in bushels, even though you don’t seed an acre with processed bushels of the harvest. Maybe it’s just payment for labor.

The first part of the game is just figuring out the basic shape of the numbers it’s asking for by guessing. How many bushels does it take to feed one person for one turn? (20.) How many acres can you harvest? (10 times the population then subtract 1.) How many bushels to seed an acre? (1.) If you typed this game’s source code in, you may have just been able to know this going in, but me I can’t read code. If you’re just playing, you repeat the first turn or two turns over and over again to hone in on these figures. This, like The Oregon Trail, is essentially a survival game, where you have resources to manage optimally and if you do poorly, you die. Except instead of dying to the elements or to zombies, you die to popular revolt.

The Prisoner [1980], one of my all-time favorite games, contains a game-within-a-game where the main character gets to pretend to be The Caretaker of their prison. It’s a hard game to win because practically everything you can do smacks the simulated prison irrecoverably out of balance, and then when you fail you are told that maybe now you understand how hard the Caretaker has it. The whole game is satire, and this minigame cuts to the heart of its point about ideological indoctrination. It might have been inspired by Hamurabi, or something else inspired by it at least.

In any case, Hamurabi and by extension The Sumerian Game (remember it?) have the same dynamic. It uses its initial difficulty, survival mechanics of penny-pinching resources immediately underlined with an overpopulation-panic scenario to shake you loose of any idea that farming alone might sustain humanity, to convince you to roleplay, to buy its mimesis, to make you empathize with the position of a managerial ruler, to naturalize it, to explain its logic, make it seem eternal and inescapable. When you win, that is, maximize acreage without the ugly business of doing it at the expense of your population, Hamurabi tells you “Charlemagne, Disraeli, and Jefferson combined could not have done better!” An odd assortment — the famously religious feudal emperor and the secular slavedriver revolutionary republican, with a Victorian imperialist conservative prime minister in the middle as if a bridge. It’s all the same to Hamurabi’s broad strokes. Charlemagne, Disraeli, Jefferson, and the real Hammurabi were all statesmen. They all had to deal with the most fundamental political question of them all: who gets what.

The trick comes once you’ve got those ratios down and can start to intelligently calculate things. (This game begs to be played with a calculator at-hand and maybe some scratch paper.) If you only use the resources at hand at the start of the game, feeding everybody and then feeding them again the next year is unachievable, you’ll find yourself in an unwinnable tailspin right away. Maintaining is not an option. You start the game in the toughest position you’re likely to be in the entire game. You’re on the backfoot, you’re overextended, there’s too many mouths to feed and not enough grain stored up to be a cushion.

There’s only two working solutions that can get you to year 4: First, you can willfully starve the population to death, so long as you don’t kill so many people in one fell swoop that they kill you. This reduces the demand on your supply to a manageable equilibrium where you can reliably feed people by the sweat of their brow, sometimes pulling a surplus when the harvest is very good and sometimes dipping into that surplus when the population rises overmuch from immigration, for the rest of the game. You muddle along from one year to the next and end up at the end either pretty close to where you started if you let off the throttle once you could and stopped throwing like 20 people a year into the engine, or with a comfortable budget surplus if you keep cosigning the population to death year after year. This austerity strategy is both morally hideous and clearly sub-optimal, though.

Second, you can commit to feeding everyone and immediately sell the 200 acres that you don’t even have the capacity to farm. In year 2, not only will you have enough barley to feed all your people and seed everything you have, but also to buy back what you just sold the year prior and then some if you want, not because of a particularly good harvest, but because you now have about two and a half times the liquid capital you started with and the price of land has fallen precipitously this year. Congratulations, you just played the real estate market and won big. You sold high and bought low. This is the winning strategy. With either strategy, you can get through to the end of the game.

As a gameplay arc, this is notable because it’s on-boarding the player by deliberately putting the most difficult circumstances right up front, such that you can’t even see most of the game if you don’t first learn how it works. The concept of on-boarding the player through their staged interactions with the game was, in my experience, really very rare before Super Mario Bros [1985] popularized it. But unlike Super Mario Bros’ gentle tutorial introducing things one by one, Hamurabi has a sink-or-swim attitude afforded by not just its simplicity and ease of quick replay but most importantly its complete transparency. The players don’t need things laid out one by one by the game, they can test things one by one for themselves.

As a story, this is fascinating to me. In this game, the market saves lives, flat out. Market speculation is here not some optional layer entirely alien to the process that produces commodities. Rather, it is forcefully shown to be absolutely central to keeping the social machine running smoothly. Without its financial input juicing it, the system breaks down and people die from poverty, that’s the trade-off this game leads with. What it makes me wonder is: Who are you buying the land from and selling it to? What is this market? There’s a historically-grounded answer, but clearly Hamurabi isn’t fussed about accuracy, and there’s obviously no textual answer either.

Land prices are random, not in the sense that they’re not the same in the same order every time you play, but in the sense that there’s no apparent logical correlation between it and any of the other information that you have, no apparent push and pull of supply and demand. If anything, there’s a vague inverse correlation between years with good harvests and years with low land prices, where you might figure it should be the opposite way around, because your neighbors must have had a good harvest too, thereby demonstrating the fertility and thus value of the land to their owners while also pushing the bids proportionally higher among other buyers who likewise struck it rich this year. Instead of working according to their own independent logic, the convolutions of the market are scripted for the benefit of the player.

This is all to say that the real estate trade, while integral to the system, itself exists outside of the boundaries of the system. Think of the thermodynamics of a natural ecosystem, with grass and a moose. The moose is fueled by the grass, but the grass can’t subsist on moose turd pie alone. It needs the power of our yellow sun, which obviously exists external to whatever happens on our planet, but nevertheless its juice feeding into the system is necessary for its continued operation. If the sun stopped shining one day, things here on Earth would immediately enter a brutal death spiral, where the only way to survive for even a little bit would be to burn up all the already-stored energy that exists within our system and die a little slower. That’s exactly how getting money out of the market works in Hamurabi. Immigration, too, is modeled as input from outside that fuels the inside, and that replenishment of the labor force (oddly the only way your labor force increases at all) is the only thing that keeps the strategy of deliberately starving your own people to death temporarily viable for the 10 years you play through.

Though this is a highly simplified model, real-world capitalism has the same need to feed from outside its own system to sustain itself without cannibalism, hence its endless thirst for expansion into “new” markets, but with the added consideration that in trading, every gain is fundamentally someone else’s loss. On a global scale, there’s no net profit, you’re just moving things around. (There are things that aren’t zero-sum in this capitalist world, but I don’t want to go on for several thousand more words right now, I’m already on a tangent.) Which brings us back to who you’re buying the land from. Whoever they are, they must be operating under the same fundamental constraints as the player. They also need to eat. And your gains are their losses. Eventually, if you’re playing towards the good ending of the game, you will have more land than you can possibly farm with your workforce, just sitting around completely fallow and feeding nobody, because it’s more profitable in arbitrage.

The beginning of the game is not the last crisis your regime faces, just the most severe, especially because you’re not prepared. It deploys further crises with delicacy: for the first 3 years, rats aren’t a problem, but in the 4th year they are a severe problem. However, this is mitigated by it being the best harvest yet in the game, such that it works out to about the same return you got last year. It could maybe catch you out if you somehow got through the first 3 years just by selling acres for food. After that, there’s another 3 years with no incident to recover from crises, though land prices are kinda high for a while. In year 6 they drop back low, real low. Now’s the time to buy! Oh, but it’s just lulling you into a false sense of security… In year 7 the rats strike again, and they bring their friend, a horrible plague! Fully half the population dies!

…We’ve done a lot of thinking about plagues these past couple years, haven’t we? I think this game that’s generally completely derelict on its ancestral educational mandate can still teach us a little something, though. Because the plague killing half the population might sound bad… but from this perspective, the capitalist manager staring at numbers, it’s secretly nothing but a boon. The plague is profit. You even get a second one in year 10 after another break to lick your wounds, which lets you juice your numbers one last time. Remember that deliberately killing your own people is a valid strategy in this game. This moment allows you to taste the benefit of sacrificing the population without having to get your hands dirty. Land prices are way up in year 7, even though if we reasonably assume our neighbors also caught the plague, that means they would suddenly have a lot of excess land that they don’t have the labor force to work, so supply should be up and driving prices way down. But you also suddenly have a lot of excess land you can’t work, on top of the excess land you bought on the cheap last turn. And you can sell every scrap of it for astronomical profit, then buy it back the next year when prices are low.

People don’t matter. They’re not even commodities to this game, they’re just numbers, a mathematical operation that chews up 20 bushels a head a turn, and if you throw another 10 bushels down on top of that for a total of 30 bushels per person, you get between 10 and 50 bushels per head in return. If you consider the 20 non-negotiable, then that 10 looks like a good deal, because it always gets made back at a minimum. But taken as a whole 30… a year with more than a break-even 3 per acre yield is an exceptionally good year. Playing the market is way more profitable. An acre farmed can only yield 5 bushels per acre at maximum, which is nice to accrue as like an interest rate on your portfolio, but an acre bought low and sold high can yield up to 11 bushels per acre. I put the strategies in opposition earlier, but there’s no reason you can’t combine both austerity and speculative trading and kill as many people as you can get away with to cut the cost of supporting their lives whilst trading fallow land back and forth to REALLY maximize your profit at the direct expense of everyone’s well-being.

It’s all an artifact of a hastily-balanced game, a trifling toy really, with no reflection on the real modern systems it’s imitating.

(Originally posted on my blog, [https://arcadeidea.wordpress.com/2022/02/21/hamurabi-1968-1973/](Arcade Idea).)