BrTedford

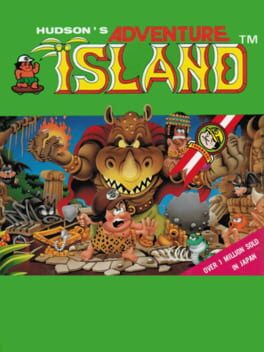

Super fast-paced, Adventure Island takes Super Mario Bros ethos of platformer as obstacle course and runs with it. Deaths are painful due to having to power up again (and you WILL want to be fully powered up), but the game has an addictive "one more try" quality that makes it a strong showing for 1986 despite its faults.

1989

Absolutely excruciating difficulty, Holy Diver plays a bit more like a puzzle game than a true action title. There is nearly zero room for error in both movement and usage of magic, requiring each room to be tackled as a precise dance between the player and the gauntlet the developers put in their way.

This is harder than Battletoads in my opinion.

This is harder than Battletoads in my opinion.

1984

Unforgiving puzzle game, but that's what makes it great. Lode Runner is all about planning, and trying to execute on those plans while being relentlessly chased down by admittedly non-threatening Bomberman clones. This version's biggest detriment is the screen scrolling, which occasionally makes it difficult to hold the entirety of the stage in your mind.

1986

Carved from the same bones as Zelda in much the same way Kid Icarus and Metroid were, Nazo no Murasame Jou asks what Zelda would be like if it were more action oriented, interested in exploration, but only as an incidental addition to the push towards the levels boss.

There is a certain satisfaction and grace to deflecting shuriken as you weave your way through swamps and castles, and I love the mechanic of bringing out your sword for a finishing blow at close range. Still, the game pales in comparison to Zelda. There is an arcade mindset the game possesses that feels decidedly old fashioned at a time where Nintendo was experimenting so much with genre and gameplay. Solid, but I'm not surprised it never gained the sort of legacy it's peers did.

There is a certain satisfaction and grace to deflecting shuriken as you weave your way through swamps and castles, and I love the mechanic of bringing out your sword for a finishing blow at close range. Still, the game pales in comparison to Zelda. There is an arcade mindset the game possesses that feels decidedly old fashioned at a time where Nintendo was experimenting so much with genre and gameplay. Solid, but I'm not surprised it never gained the sort of legacy it's peers did.

Nearly as good as the first Super Mario Bros, 2 refines the level design to take the mechanics of the game to their logical conclusion without edging into the territory of "Kaizo hack". This is still a standard Mario game after all, and you won't find the strict unyielding requirements for movement you would in a contemporary hack.

What you will find are brutal enemy placements, difficult jumps, and a sort of winking elbow to the shoulder from Nintendo. This is a game to be played only if you have truly mastered the original, and stands as a sequel with a difficulty curve ethos towards player progression that you don't see often these days.

What you will find are brutal enemy placements, difficult jumps, and a sort of winking elbow to the shoulder from Nintendo. This is a game to be played only if you have truly mastered the original, and stands as a sequel with a difficulty curve ethos towards player progression that you don't see often these days.

1982

1982

Endlessly fascinating as an early console RPG. I could break out the superlatives and discuss the games early roguelike elements, it's multiple progression options, or it's open-world nature, all of which are a bit on the simple side. The fact remains that this is an incredibly ambitious title that began tackling questions about how a console RPG could be designed in a meaningful way.

It is also shockingly playable, a feat I chalk up to it's speed and relatively sturdy design.

It is also shockingly playable, a feat I chalk up to it's speed and relatively sturdy design.

You know you can start hovering out of the holes the moment you fall in right? You don't actually need to wait to hit the bottom.

A super ambitious title hampered by a soul crushing timeline passed down from on high by the Powers That Be, and then dragged through the mud for decades by nerds looking for a cheap laugh, ET has some cool ideas (context sensitive abilities that force you to pay attention to your position in an open-world environment) that may not all come together elegantly, but I'm happy they tried.

A super ambitious title hampered by a soul crushing timeline passed down from on high by the Powers That Be, and then dragged through the mud for decades by nerds looking for a cheap laugh, ET has some cool ideas (context sensitive abilities that force you to pay attention to your position in an open-world environment) that may not all come together elegantly, but I'm happy they tried.

1989

Imagine you have been tasked with creating a new game for the 2600 that can compete with the sorts of titles one-sided Atari rival Nintendo was putting out in the late 80's. Imagine you look to The Legend of Zelda and decide you want to create something that at the very least resembles the structure and content that game was bringing to the table. Miraculously, Secret Quest sort of pulls it off.

Make no mistakes, this is still a 2600 game. You won't find expansive overworlds, complex enemy patterns, or a soundtrack. What you will find is an ambitious action-adventure with exploration, fast-paced combat, saving in the form of passwords, and even a little cinematic flair with the countdown to each space station's self destruction.

I love ambitious titles. Creativity and the reach towards something that could maybe turn out incredible will always beat the competent execution of a tired concept in my book. The world is richer for Secret Quest's existence, even if it will never be able to take on Zelda in a head to head contest.

Make no mistakes, this is still a 2600 game. You won't find expansive overworlds, complex enemy patterns, or a soundtrack. What you will find is an ambitious action-adventure with exploration, fast-paced combat, saving in the form of passwords, and even a little cinematic flair with the countdown to each space station's self destruction.

I love ambitious titles. Creativity and the reach towards something that could maybe turn out incredible will always beat the competent execution of a tired concept in my book. The world is richer for Secret Quest's existence, even if it will never be able to take on Zelda in a head to head contest.

1983

It's a Dracula sim for the Intellevision from 1982, what's not to like? Prowl the night, lure victims out of the house by playing ding-dong ditch, and create an army of zombies that can be controlled by a friend.

It's not the deepest or most riveting game out there, but it is incredibly novel, and honestly too cool to ignore.

It's not the deepest or most riveting game out there, but it is incredibly novel, and honestly too cool to ignore.

1994

Fantastically ambitious but plagued by awkward controls and sometimes infuriatingly obtuse combat. This is the sort of game you are practically required to cheese in order to make any significant progress, but the bones of a truly ambitious title are here, and that makes the game worth a look for those interested in seeing the evolution of early 3D console games.