flaco

Top 5 over there is just the last 5 games to enter my group of all-time favorites

Badges

Loved

Gained 100+ total review likes

GOTY '23

Participated in the 2023 Game of the Year Event

Trend Setter

Gained 50+ followers

GOTY '22

Participated in the 2022 Game of the Year Event

Well Written

Gained 10+ likes on a single review

Liked

Gained 10+ total review likes

Epic Gamer

Played 1000+ games

Organized

Created a list folder with 5+ lists

3 Years of Service

Being part of the Backloggd community for 3 years

Best Friends

Become mutual friends with at least 3 others

Busy Day

Journaled 5+ games in a single day

GOTY '21

Participated in the 2021 Game of the Year Event

On Schedule

Journaled games once a day for a week straight

Popular

Gained 15+ followers

Noticed

Gained 3+ followers

Elite Gamer

Played 500+ games

Gamer

Played 250+ games

N00b

Played 100+ games

Favorite Games

1475

Total Games Played

041

Played in 2024

165

Games Backloggd

Recently Played See More

Recently Reviewed See More

The original Street Fighter is an infamously terrible game. There’s only one character to play, the controls are awful, and no one has ever done a special move in it on purpose. These are the things I’ve heard about the game for as long as I can remember, but as the existence of this piece might suggest, I think there’s actually more to the story. Street Fighter 1 is not only a good deal better as a game than its abysmal reputation suggests, it also serves as an intriguing and inspiring entry in the career of its creator that deserves more than we give it.

In Street Fighter 1, you maneuver on a 2D plane and try to land hits on your opponent by selecting from an arsenal of six normal attacks and three special moves (the same fireball, uppercut, and hurricane kick that fighting game players know today). You can jump to change your position or angle of attack and put pressure on a guard that can be either high or low. You can walk forward and backward and threaten space with your normals, control the screen with fireballs and dragon punches… it's a fighting game! There may not be any throws or combos or okizeme, and what is there may only half-work in the first place, but the blurry image of 2D fighting fundamentals is absolutely here on display, in a way that makes it easy to see how games just a few years later would pick up that torch and run with it. It may pale in comparison to its sequel, but it’s hardly the clueless jumble that many people make it out to be. It’s easy to see the future just by playing it.

Of particular note to me is the way special moves work. Just about every single conversation about Street Fighter 1 features the derogatory claim that special moves are more or less impossible to execute in the game. This is actually not true at all! Anyone can pull off specials in SF1, they just need to know the trick. See, possibly as a result of the game’s conversion from its original (awful) pneumatic punching pad controls to a more standard (but still innovative) six pushbutton layout, special moves in SF1 are executed not when the player presses a button down, but when they release a button.

STREET FIGHTER 1 HAS NEGATIVE EDGE, WHY DID NOBODY EVER TELL ME THIS.

When you use button releases for your special move inputs rather than button presses, throwing fireballs is about as easy as in any other game. What fascinates me about this is that these moves require you to know the specific trick to them. Fighting game players today sometimes feel nostalgic for the arcade era, an age where information traveled slowly via smaller-scope, person-to-person conversation within a community, rather than the current online environment where games are immediately picked apart and put back together in a global whirlwind, and knowledge circulates so quickly on social media that the “save that for nationals” mindset simply has no reason to exist anymore. Yet here we are in 2024, and an old game that sits at the very cornerstone of the whole genre has hidden technical knowledge that the vast majority of people don’t know about. Here is a game where to learn its secrets you still have to be told them by someone in the know. How cool is that? I only learned this quirk of the special moves from a random forum post from like fifteen years ago, and from all the conversations I’ve seen about the game most people don’t know about it either! I think that mystical, mysterious quality is something rare and special nowadays, and SF1 has it.

Outside of its merits as a fighting game (which I admit are pretty slim, I wouldn’t want to play it competitively), Street Fighter 1 inspires me because I can feel the hand of its creators in the game, especially that of its director Takashi Nishiyama.

SF1 feels to me like a key touchstone in a creative project Nishiyama was embarking on for much of his career. In 1984, three years before SF1’s release, he designed Kung-Fu Master, a game frequently credited with birthing the beat ‘em up genre. In Kung-Fu Master, the player moves across the screen, beating back enemies with a punch button and a kick button that they can also use while jumping or crouching for aerial or low attacks. At the end of the first stage, an enemy martial artist stands in the player’s way, and to defeat them the player has to reactively block the enemy’s attacks either high or low while sneaking in their own strikes, or else briefly back up out of the enemy’s range and then take advantage of their whiffs. It may be primitive looking, but years before even SF1 you can easily find in Nishiyama’s games the embryonic form of what would become classic fighting game combat.

Several years later Nishiyama would also design Avengers, a top-down beat ‘em up where players took the role of a fighter with punch attacks, kick attacks, and even a special whirling roundhouse move that, to me at least, immediately calls to mind a Street Fighter tatsu. It has the mark of an artist circling around an idea in their work. When I play games like these it feels to me that their creator was striving towards something, taking multiple stabs at an idea they found exciting.

Despite saying in his rare interview appearances that he only ever designed for the mass market and didn’t make games to cater to his own personal taste, at the time of Street Fighter’s development Nishiyama was an active student of martial arts, and in another interview he speaks with excitement about the various fighting styles he wanted to have represented in Street Fighter, noting that seeing those mismatched styles square off against each other would be a key appeal. He designed other games that don’t resemble Street Fighter at all of course, scrolling shooter games and the endless runner genre ancestor Moon Patrol. But here is a designer who kept coming back to these 2D combat games, always adding in little complications like separate punch and kick buttons and varied block-heights, because they made the games more fun to play, but maybe also because there was something about those complications that he needed to explore.

We give a lot of credit to many artists, our assorted Lynches and Kojimas and Miyazakis and others, for navigating a path through their own creative fixations across the breadth of their work. I can’t claim to know anything about the mind of Takashi Nishiyama, but in his games I feel that creative fixation. Fighting games are very important to me, and I truly think a game like the original Street Fighter deserves to be seen positively in the context of its creators’ work. After SF1, Nishiyama would leave Capcom to head his own division at SNK, and soon after he would direct Fatal Fury, a more sophisticated take on fighting games that he has likened to his own Street Fighter II. Together with the team he brought with him from Capcom, including his frequent collaborator Hiroshi Matsumoto (who is essential to the history of the genre in his own right, having the planner credit on Street Fighter 1 and numerous executive producer credits on later fighters), Nishiyama would be at the forefront of SNK’s development teams, leading the company to become the pillar of the fighting game genre we know them as today. He later founded Dimps, the studio that developed Street Fighter IV. The guy just couldn’t stay away from good old punching and kicking games.

It heartens me as a player, designer, and lover of videogames that it's possible to play these games and feel something so human in them, to see an artist toying with an idea, teasing out its essence and refining their craft. Street Fighter 1 feels like an important piece of that to me. It may not be a great fighting game, but it was part of something special, and to me that’s worth celebrating.

This review contains spoilers

Dragon Quest XI is full of endlessly endearing characters, constantly pleasurable combat, and a sense of warmth and wonder that few experiences can rival. I'd call it one of my favorite games. But, the thing my thoughts kept returning to for days after finishing it was Act 3. What the hell is it??

After DQXI's antagonist is defeated and the ending credits roll, a lengthy additional scenario for the player begins, generally referred to as the Post-Game or "Act 3." Taking place after the end credits, it's framed as an extra optional adventure, though some story elements from the main game only see their ultimate resolution in Act 3. I decided to play through Act 3 in order to see everything that DQXI had to offer. I loved the main game, after all!

I'd characterize my initial experience with Act 3 with two words: Whiplash and bafflement. Why why why is this game un-sticking its own landing to have me undermine its most emotionally impactful moments?

The scenario of Act 3 is built around using time travel to undo the death of the character and party member Veronica. Her death happens suddenly and silently in the main story; the player won't learn that she is dead until many hours after she sacrificed herself. There are no tearful last words, no encouragement to finish the quest from the dying, the player just gets separated from her at one point, and instead of a reunion, there's her body.

In a game principally concerned with the undiluted joys of love and friendship and the appeal of just spending time with people you care about, Veronica's death is titanic. DQXI semi-frequently punctuates its usually lighthearted fairy tale tone with moments of sadness, loss, and despair to contrast with and underscore the importance of its joyful themes, but Veronica's death is a step beyond. It constitutes a massive, tangible loss for both the principal characters and the player. Veronica stops being a playable character, she can no longer be a piece of any party composition in the dozens of battles to come, she won't be hanging out in camp, she won't have any optional dialogue, she won't feature in any story scenes going forward. These things may seem obvious but in the tens of hours I had been playing up til then, Veronica had become a staple of my experience in the game. She was an integral member of my band of friends and I had expected to return her to the party when I found her after all the characters were scattered at the end of "Act 1." After spending so many great hours with DQXI, her death cast a shadow of sadness over the rest of my experience.

She's survived by her sister Serena, who resolves to continue adventuring with the player and to live for the both of them. She cuts her hair and inherits a piece of Veronica's spirit, and from then on in gameplay Serena possesses the powers and abilities of both herself and her sister. She quietly carries Veronica's memory with her for the rest of the game, and every time the player uses her to cast one of Veronica's spells during combat they are reminded that no one is ever truly gone forever. It's a simple, beautiful way to imbue the basic fabric of a game with emotional resonance. Act 3 is about taking all that away.

That is maybe a bit uncharitable to say, but it is fundamentally true. Act 3 sees the hero traveling back in time to keep Veronica from dying and then saving the day all over again with her in tow. In this reality, Serena never suffers that loss and never resolves to remain strong in the face of grief. The bonds of the party are never strained and strengthened by the loss of their loved one. Similarly, other hard lessons are unlearned as well. Another party member, Erik, has his confrontation and reconciliation with his sister erased and replaced with an altogether more abridged and tidy reunion. Michelle the mermaid never sees her tragic story concluded, Sylvando never finds purpose forming a traveling troupe to bring joy to a despairing world. People all over Dragon Quest XI's world never experience the dark era of strife brought on by the game's antagonist. In the main story the hero fails to stop him at the end of Act 1, and the player is made to live with the cataclysmic consequences while experiencing both struggle and hope in the process of rebuilding. In Act 3's revised history, all this darkness is made squeaky clean by comparison. In a game that previously seemed to be putting forth the importance of hope and perseverance in the face of life's tragedies, Act 3 seems to be saying that hardship is fundamentally inappropriate to a happy life, and that it would be better for those hard lessons to never be learned at all, fantasizing that all the bad in the world can be magically painted over, completely exiting any emotional reality that a player could experience themselves in their own life.

This is roughly the message I got from Act 3 at first blush. However, I want to challenge my own premise here, because after some time and a lot of thought, I've come to view Act 3 in a different way that, while not fully making me love its direction, helps me to appreciate and reconcile it with the overall shape of DQXI as a piece of art.

For me to make peace with Act 3, I first had to accept that it's primarily an exercise in wish-fulfillment. At the end of the main game I had so much affection for those characters that a chance to spend dozens more hours with them was everything I could ask for! Act 3 is wish-fulfillment on a deeper thematic layer too. The main story spends a lot of its focus on imparting its ostensibly light-hearted storybook narrative with a sense of emotional tangibility. It reaches out to the player with moments of irrevocable sadness followed by moments of joy, friendship, and solidarity despite it all, and asks the player to see the value in these things. In reality you can't take back regrets or bring back the people you lose. The purpose of Act 3 is to willfully engage in a fantasy contrary to the rest of the game, though just because it's contrary doesn't mean it doesn't have value.

By doing the impossible and rewriting history in Act 3, the player and the hero perform a service out of love for the people they care about. Their friends will never know the strife that might have been. Given the opportunity, What lengths would you not go to, to protect the ones you love from pain? Given that very opportunity, the hero of Dragon Quest XI changes the entire fabric of the world, because reality is a small price to pay to see a friend smile again. The world is already full to bursting with hurt and sadness, it won't miss the little that you take away.

Act 3 taps into the impulse to wish you could truly save the day and make everything okay for the people that matter to you. In real life, this can be an impossible and even unhelpful idea when pushed too far, and I'm personally more drawn to the world of real emotional consequence presented by the main story, so the real Dragon Quest XI will always sort of end for me at the conclusion of Act 2. But Act 3 lets the player spend time in the fantasy, spend more time with their friends, be the hero they cannot be in real life. It's a videogame, why not take this chance to live inside it as you cannot outside it? As a purely additional coda to a game all about the connections we make, it strikes me as somewhat beautiful that in Act 3, you never have to say goodbye.

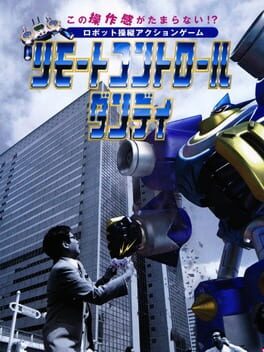

Playing this I can see how all these great elements are still embryonic in Remote Control Dandy. Everything in this game is begging to be pushed further. It shows me a blueprint to a masterpiece videogame that exists in my head.

I intend to investigate this little genre further and see if that masterpiece exists elsewhere as well.