rubenmg

1986

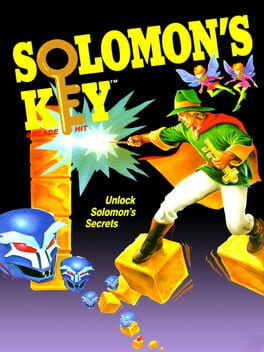

There is some undeniable wit in its very own premise of being able to create and destroy (part of) the map at will as a puzzle solver tool, however, the strength of the premise never finds a worthy match in the design of any level.

Sure, there are enough smart elements to carry the game, but as the levels are formed into puzzle boxes they are underwhelming, with solutions usually taking about 3 or 4 not that clever steps to clear and few rearrangements of expectations within the given rules, more often than not, it feels like it has nothing to twist even. The worries of not being competent in following the premise intelligence are confirmed by the addition of the action elements.

If the puzzle game is well thought out at its premise, the same cannot be said about the action. At best, it will give a few surprises through exploration or luck, but it will often feel as a detriment in the way to make the game look more interesting. Sure, it's important to add a timer to twist a bit more what a possible solution can be, but, apart from that, action usually will mean just a mere transit (regardless of its difficulty to execute) between solving a level and discovering a new one. It seems even more clear looking at how the levels are thought out in a very tight tile distribution, and realizing that the time limit is just a real time, and less intellectually interesting, number of movements limit.

To envision Solomon's Key as a pure puzzle game is not only possible but a revelation that there might have been a better similar game and that the level design always falls behind what the premise suggests. Thinking about Solomon's Key as an action game, it’s just too stiff to stand on its own, even the jump, the only action with some uncertain momentum, is an easy tile distance calculation. And I’m afraid most of the time will be spent dealing with the latter type of game.

Sure, there are enough smart elements to carry the game, but as the levels are formed into puzzle boxes they are underwhelming, with solutions usually taking about 3 or 4 not that clever steps to clear and few rearrangements of expectations within the given rules, more often than not, it feels like it has nothing to twist even. The worries of not being competent in following the premise intelligence are confirmed by the addition of the action elements.

If the puzzle game is well thought out at its premise, the same cannot be said about the action. At best, it will give a few surprises through exploration or luck, but it will often feel as a detriment in the way to make the game look more interesting. Sure, it's important to add a timer to twist a bit more what a possible solution can be, but, apart from that, action usually will mean just a mere transit (regardless of its difficulty to execute) between solving a level and discovering a new one. It seems even more clear looking at how the levels are thought out in a very tight tile distribution, and realizing that the time limit is just a real time, and less intellectually interesting, number of movements limit.

To envision Solomon's Key as a pure puzzle game is not only possible but a revelation that there might have been a better similar game and that the level design always falls behind what the premise suggests. Thinking about Solomon's Key as an action game, it’s just too stiff to stand on its own, even the jump, the only action with some uncertain momentum, is an easy tile distance calculation. And I’m afraid most of the time will be spent dealing with the latter type of game.

2021

A game that is conscious about its shonen references but isn’t ashamed of them, rather uses their strength to irradiate the energy of being young. Rivals, superpowers and especially rebelling against what you are supposed to be and choosing who you want to be.

But that’s where the consciousness stops. Didn’t reflect too much about anime filler it seems. Something as crucial as the combat system is just sitting there. The most inanimate way to represent dodgeball, obviously blander with each filler encounter, but instead of rebuilding it from scratch, removing it, or at least reducing it, just more variations keep being added hoping to do the coverup. A juvenile talk about being yourself at the same time as it follows the rules of old just because of tradition.

But that’s where the consciousness stops. Didn’t reflect too much about anime filler it seems. Something as crucial as the combat system is just sitting there. The most inanimate way to represent dodgeball, obviously blander with each filler encounter, but instead of rebuilding it from scratch, removing it, or at least reducing it, just more variations keep being added hoping to do the coverup. A juvenile talk about being yourself at the same time as it follows the rules of old just because of tradition.

2013

I have the feeling that an important ingredient in Hexcells taste is in the familiarity of the base, half minesweeper, half sudoku (some say Picross, but I don't know it first hand). It’s simple to understand because the rules are always simple. The interest escalates quickly by taking advantage of handmade levels where the positioning is carefully considered to the detail, so that you never need to guess while you still need to slowly examine all the hints to advance without failing.

The great understanding of space is as important as the great understanding of rhythm. In just one hour, the game achieves tranquility, which is clearly pointed at in its visual and sound style, through an impeccable complete concentration. When you realize, you've gone through the whole game in a single one-hour session.

This is what Plus fails to understand from the get go. It's not a bad premise to begin from where the original left off, throwing much harder levels early on. But the Plus isn’t only in the difficulty but also in the size and length. What used to be a concentrated session is now a collection of huge, tedious levels where you spend too much time counting, not deducting, and where you keep tabbing out frequently to clear your mind, something unthinkable in the first one. Even worse are the new hints. The hints with question marks may still have some grace depending on their positioning, however the hints that tell you how many blue hexes are there in a range, represented by an area that looks terrible and hard to read often, multiply the already tiring counting by having to count again, now in circles. And that without going into the levels that rely on this new idea essentially.

That infinite Hexcells games can be made was obvious. That a key essence from the first one was to be concise and not needing anything else, not so much it seems.

The great understanding of space is as important as the great understanding of rhythm. In just one hour, the game achieves tranquility, which is clearly pointed at in its visual and sound style, through an impeccable complete concentration. When you realize, you've gone through the whole game in a single one-hour session.

This is what Plus fails to understand from the get go. It's not a bad premise to begin from where the original left off, throwing much harder levels early on. But the Plus isn’t only in the difficulty but also in the size and length. What used to be a concentrated session is now a collection of huge, tedious levels where you spend too much time counting, not deducting, and where you keep tabbing out frequently to clear your mind, something unthinkable in the first one. Even worse are the new hints. The hints with question marks may still have some grace depending on their positioning, however the hints that tell you how many blue hexes are there in a range, represented by an area that looks terrible and hard to read often, multiply the already tiring counting by having to count again, now in circles. And that without going into the levels that rely on this new idea essentially.

That infinite Hexcells games can be made was obvious. That a key essence from the first one was to be concise and not needing anything else, not so much it seems.