sam_gray

Starts off strong, with mercenaries in the Middle East, serious digressions on the war economy, and the genetic horror of Metal Gear Solid 2 taken to its logical end point. War machines braying like cows is wonderfully disturbing, and while the nanomachines are in some respects too-easy solutions to deus ex machina, the idea of every soldier and weapon being subjected to the whims of a cloud-based operating system (with no clear corporate owners) is obviously resonant. The balance between gameplay and cutscene shifts heavily towards the latter compared to earlier entries, but I was surprised by how little this bothered me - I treated it like a multimedia project, and the split-screens and ability to move around the cutscene space in briefings felt inspired, especially the (awesome) divided boss fight with Vamp and the Gekkos.

As is often the case with Kojima, though, a degree of sexism emerges, and the backslide from the (mostly brilliant) politics of Snake Eater is dramatic. A secondary character having her top irrationally unbuttoned the whole time soon pales compared to the Beauty and the Beast corps, some of the most ill-conceived characters I’ve ever seen in a game. It’s possible that these repetitive encounters - with a leering camera, skin-tight character designs, and stupid as shit writing - are a conscious protest against being forced to include fan-pleasing boss fights by corporate overlords. I don’t care - it doesn’t work and it’s gross.

But this grossness gets to the heart of the matter, really, which is that this is a game that seems to hate itself. Or at least the part of itself that glorifies war. While the others indulge in plenty of auteurist smuggling, offering nuanced critique of American foreign policy, nuclear warfare, genetics, etc, they are, on their surface level, entertaining - a power fantasy with guns and gadgets. There are more of those here than ever, but the fantasy is gone, Snake a hacking husk whose adventures are more grim and pointless than ever. How else to justify the awkward gunplay that barely bothers with setting up stealth situations, or the self-parodic repetition of past glories? The fact that the fan-despised Raiden is re-introduced as a supernaturally powerful ninja who ends up losing both his arms and holding his sword between his teeth is part and parcel with the camp ludicrousness of the series, and an indicator of something new - a resentment toward player expectation.

This even extends to the game’s hideous look, embracing the bloom-filled browns that now seem typical of the PS3 era. Perhaps it’s more fascinating now than it was at the time as a time capsule of a different era - a turbulent afterbirth of the War on Terror, and a franchise eating its own tale. The final, long cutscenes are true to form: excessive, silly, but also thoughtful and oddly moving. ("Snake had a hard life..." / "This is good, isn't it?") The worst Metal Gear game I’ve played, and still undeniably touched by genius.

As is often the case with Kojima, though, a degree of sexism emerges, and the backslide from the (mostly brilliant) politics of Snake Eater is dramatic. A secondary character having her top irrationally unbuttoned the whole time soon pales compared to the Beauty and the Beast corps, some of the most ill-conceived characters I’ve ever seen in a game. It’s possible that these repetitive encounters - with a leering camera, skin-tight character designs, and stupid as shit writing - are a conscious protest against being forced to include fan-pleasing boss fights by corporate overlords. I don’t care - it doesn’t work and it’s gross.

But this grossness gets to the heart of the matter, really, which is that this is a game that seems to hate itself. Or at least the part of itself that glorifies war. While the others indulge in plenty of auteurist smuggling, offering nuanced critique of American foreign policy, nuclear warfare, genetics, etc, they are, on their surface level, entertaining - a power fantasy with guns and gadgets. There are more of those here than ever, but the fantasy is gone, Snake a hacking husk whose adventures are more grim and pointless than ever. How else to justify the awkward gunplay that barely bothers with setting up stealth situations, or the self-parodic repetition of past glories? The fact that the fan-despised Raiden is re-introduced as a supernaturally powerful ninja who ends up losing both his arms and holding his sword between his teeth is part and parcel with the camp ludicrousness of the series, and an indicator of something new - a resentment toward player expectation.

This even extends to the game’s hideous look, embracing the bloom-filled browns that now seem typical of the PS3 era. Perhaps it’s more fascinating now than it was at the time as a time capsule of a different era - a turbulent afterbirth of the War on Terror, and a franchise eating its own tale. The final, long cutscenes are true to form: excessive, silly, but also thoughtful and oddly moving. ("Snake had a hard life..." / "This is good, isn't it?") The worst Metal Gear game I’ve played, and still undeniably touched by genius.

2022

Likely the most absorbed I've been in a game in a long time (my playthrough clocked in at around 90 hours), so I might have just been so oversaturated by the end that I'm already underrating an instant classic. It reminded me less of Dark Souls than World of Warcraft, with an amazing variety of distinctive zones and enemies designed to catch you off-guard. Everything that's unbalanced and weird about it works in its favour, creating a world with loose rules designed to be broken - Margit is a barrier that teaches you to explore further, Rahdan teaches you that there's no shame in summoning, Malenia teaches you that life is unfair sometimes and then you die. An uncompromising investment in every one of Miyazaki/Fromsoft's pet themes, obsessions, and mechanics, with a real effort made with secondary characters this time around (Iron Fist Alexander MVP). Also just a bit overfamiliar, with a story so vague that it evaporates to nothingness by the end. I don't play these for narrative reasons, though Dark and Demon Souls had a clear purpose in mind with their downward, rotting trajectories, whereas this - with its huge map, buzzing with life - hardly feels like a world in decline. Still probably the coolest game ever made.

Really dug this for a while. The shooting is awkward, but there’s a blunt verisimilitude to the gunfights, an attention to detail with e.g. your teammates giving you ammo when you’re low, or where being revived with adrenaline too frequently leads to an overdose. The game apes Michael Mann better than most, most blatantly with the nightclub shootout - the screaming crowds are a great touch - or the later Heat-inspired getaway on the streets of Tokyo. What it doesn’t attempt to capture is Mann’s romance. There’s no attempt to lend Kane & Lynch’s quest justification of any sort. They’re bad men - in Lynch’s case, bad in a clinically insane kind of way - and the game is at its best when exploring this blackly comedic dynamic, where one tries to rein the other one in but both, predictably, bring out the worst in each other. Unfortunately, the game falls off a cliff at the midway point, turning into an awful guerrilla warfare shooter that’s full of insanely difficult bullshit. But points to its grimy B-movie vibes until then.

2022

Seven variations on a genre, a conceptual gambit with parallels in literature - B.S. Johnson's The Unfortunates, or Chris Ware's Building Stories - but executed in a way that feels wholly unique to video games. The narrative is broadly the same each time - an outsider must work with others to overcome an overriding threat - so the game becomes "what is the game?" The worst chapters are where either the gameplay goals are too convoluted to grasp easily (Near Future) or too simple to get much out of (Present Day); the best, conversely, present a straightforward scenario and then skew it with a unique gameplay hook. Pastiche is key to player understanding: it's easy to grasp, for instance, the Wild West's Sergio Leone / Magnificent Seven scenario, but making the player's tendency to explore space for items in an RPG instead mandatory and time-sensitive lends it striking urgency. Imperial China offers what seems to be an appealing reverse on progression, placing you in the shoes of a tutor who lends his three disciples EXP by fighting them, only to pull the rug out with the sudden consequences of favouring a certain party member. And Prehistoric, hilariously, does away with dialogue altogether, relying entirely on animations and cutscene blocking to impart information. The best of the bunch is the Distant Future chapter, which removes combat and instead presents a survival horror scenario where "progression" is almost abstracted, dependent again on exploring space - a beautifully designed spaceship - and then complicating the player's relationship to the space with the sudden introduction of an external threat, similar to Alien: Isolation. The last two chapters are a slog, as the narrative novelty becomes exhausted and the focus goes back to combat - but this excellent remaster reveals an ambitious and exciting game that is well ahead of its time, and perhaps more deserving of the reputation that its successor, Chrono Trigger, has since cultivated.

1998

Important, a classic etc. that nonetheless vacillates wildly between being brilliant and infuriating - it’s a bit of a chore to actually play. The top-down perspective makes the actual 3D space irrelevant for large stretches as the radar does the heavy lifting, though there’s still a tendency to get shot from off-screen, and actually aiming at anything is a nightmare. The characters are all quite badly written, vomiting up their backstories and overexplaining every single moment of subtext ad naseum to Snake’s increasingly hilarious bewilderment, leading to exchanges like: “I’m feeling sad.” “Sad?” “Yes, sad. It’s when the endorphins in your brain don’t fire enough, leading to a lack of energy and motivation.” “I didn’t know your brain controlled your feelings...”

But something that still felt fresh was the Codec, where every one of your contacts says something different every time you walk into a different room, or do something notable - e.g. equipping the cigarettes to get scolded, or repeatedly ringing one until they ignore you. There’s a conscious effort to erase the barrier between gameplay and “story”, which is usually treated as a separate, isolated quality in video game criticism instead of inherent to game-feel. I was impressed with the torture sequence - not only is failure here an option, but it’s the more interesting one, undermining the pastiche of Hollywood action heroics and paying off with a suitably down climactic beat. And while I wasn’t always impressed with the boss fights (especially the gimmicky Psycho Mantis) there’s an admirable sense of experimentation in making them all different. The pacing and build-up to each works well, and there’s some effort to complicate our relationship to them as “enemies”, e.g. Grey Wolf embracing pain. (My favourite was Vulcan Raven and his mini gun, which plays to all the strengths of the stealth gameplay.)

Admirably anti-war in its sentiments, also pretentious, sexist, and with laughable stabs at pathos - though this is, as far as I can tell, Hideo Kojima’s whole deal. Auteurism sometimes demands you take the rough with the smooth.

But something that still felt fresh was the Codec, where every one of your contacts says something different every time you walk into a different room, or do something notable - e.g. equipping the cigarettes to get scolded, or repeatedly ringing one until they ignore you. There’s a conscious effort to erase the barrier between gameplay and “story”, which is usually treated as a separate, isolated quality in video game criticism instead of inherent to game-feel. I was impressed with the torture sequence - not only is failure here an option, but it’s the more interesting one, undermining the pastiche of Hollywood action heroics and paying off with a suitably down climactic beat. And while I wasn’t always impressed with the boss fights (especially the gimmicky Psycho Mantis) there’s an admirable sense of experimentation in making them all different. The pacing and build-up to each works well, and there’s some effort to complicate our relationship to them as “enemies”, e.g. Grey Wolf embracing pain. (My favourite was Vulcan Raven and his mini gun, which plays to all the strengths of the stealth gameplay.)

Admirably anti-war in its sentiments, also pretentious, sexist, and with laughable stabs at pathos - though this is, as far as I can tell, Hideo Kojima’s whole deal. Auteurism sometimes demands you take the rough with the smooth.

A fun, imaginative Western pastiche with an explicit focus on capitalism that eventually morphs into something deeper - one that really acknowledges the racial and historical weight of its American iconography. The other Oddworld games tackle this too, but they're logy where this is three-dimensional, free, and exciting. By default, one of the best games about the transgender experience.

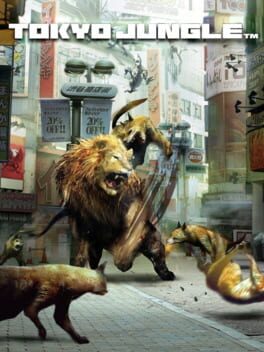

2012

The reputation on this one was Japanese and Weird, which is certainly true of a story mode that goes to some crazy places. But it’s the survival mode that best captures Werner Herzog’s view of nature, encouraging "no kinship, no understanding, no mercy". The absurdity of seeing a Pomeranian demolish a gazelle in slow-motion soon gives way to the terror of an empty hunger bar with no food in sight, or being ambushed by a gang of predators, hidden by the cover of rain - with thrumming techno music and stat-boosting challenges further driving the brutal tension of a literal dog-eat-dog world. Its genius lies in the random events and weather changes that discourage any kind of complacency. You must feed, breed, and hide to survive, but most importantly keep moving, as you never know when your section of the city will turn against you. It's clearly the best game ever made about global warming. Buy it while you still can!