Legendary kusoge that deserves every bit of heinous recognition it gets. One of the most mean-spirited jokes in video game form. Legit recommend trying it yourself and reading the history of its development. I can't decide if I should score it low for being as hateful as it is or high because of its legacy and the impact it left.

More people have walked on the moon than have beat Takeshi’s Castle [1986-1990], the TV game show which involved about 100 people attempting to win every single episode, for 131 episodes. Rumor has it that this game show was directly inspired by Super Mario Bros [1985], which I cannot find a reliable and direct source for, but which seems extremely plausible just from looking at how the show works. It’s all physical challenges of the kind Mario faces all the time, jumping over walls, swinging on ropes, clearing gaps, et cetera. (Because it was an international success in export, it was the show responsible for the anglophone world’s idea of a generic wacky madcap Japanese game show and may or may not have either originated or codified and popularized the concept, though the fad it began seems to have ended in Japan around the 2000s, while its influence kept percolating elsewhere around the world in shows like Wipeout [2008-2014/2021-2022].) The hundred contestants must get through this obstacle course without failing once or they will be disqualified, showing a conceptualization of the lives system not as like, the same Mario across alternate timelines, but as separate individuals making their own attempts, slowly filtering out until statistically someone is finally good or lucky enough to succeed against these obstacles which are extremely difficult but not quite impossible.

I see it said a lot, as basically a truism, that most or all video games are a “power fantasy.” I’ve been thinking about it and I very much disagree. There are surprisingly few games that offer up little-to-no resistance to the player enacting their will and therefore having maximal power over the game world. Rather, conventional game design is always throwing caltrops and obstacles and restrictions in front of the player. They are disempowerment fantasies, offering surmountable challenges to stimulate the player like a predator in a zoo hunting a pumpkin full of ground beef.

In Super Mario Bros, Bowser is the level designer. Takeshi Kitano cast himself as Bowser, as the villain, the bad guy in the castle. Takeshi Kitano played a lot of bad guys in movies in the 1980s (a serial killer, a cult leader, hitmen,) as his way of bucking against the unhappy confines of his newfound celebrity as a comedian and fairly ubiquitous TV light entertainment presenter type and establish himself as a serious artist, though this strategy of his would only pay off for him in the 1990s. In Takeshi’s Castle, the oppositional relationship between hero and villain is all just transparent kayfabe, it’s just for fun and really for the benefit of the hero. Really, it’s the obstacle course itself that gets to be the star of Takeshi’s Castle, it simply has more screentime than Takeshi, his castle, or any given contestant or cast member. Each anonymous contestant primarily expresses and defines their on-screen character through their relationships to the castle and how each unique approach contrasts with the ones we’ve already seen. They’re always reacting.

There’s 2 different stories of how Takeshi Kitano came by his showbiz success. There’s the short version, where it was all a fluke and he was incidentally working as a busboy and then got thrust up on stage, and the longer less-abridged version where he dedicates himself to a career in comedy through hard work and apprenticeship, deliberately working as a busboy in a particular circumstance in order to create his own luck. These stories are technically not contradictory, but they paint very different pictures and accordingly get deployed in different rhetorical circumstances. This slipperiness of mythology both allows the public character of Takeshi Kitano to be different things as the situation demands, and also suits his brand of being a multifaceted chameleon and jack-of-all-trades. It does make my life hard, though, because I’m not a very good researcher and can’t read Japanese, so the most I can do is skeptically position rumors and legends. As best as I can tell, Takeshi Kitano has written at least four autobiographies, none of which have been translated to English and most of which seem to focus on his life before fame, with various spins, such as Takeshi-Kun, Ha! [1985], which is a lighthearted children’s book about getting up to kiddie hi-jinks, or Akasuka Kid [1988], the aforementioned long version of his rise-to-fame tale, both of which got adapted to TV miniseries.

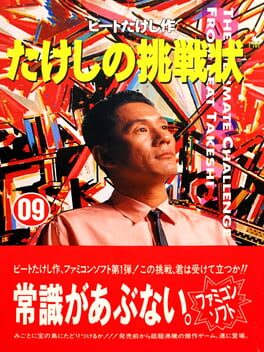

Takeshi Kitano got that start in showbiz as a “manzai” comedian in the 1970s, in the group The Two Beats (hence his nickname Beat Takeshi.) Manzai is a kind of stand-up comedy with two comedians, a funny guy and a straight man ala Abbot and Costello or a vaudeville routine or a Socratic dialogue. Usually in this sort of set-up, both participants get punchlines one way or another, but not in The Two Beats. Beat Takeshi’s routine was to be a verbal steamroller, going up there and essentially doing a solo stand-up set where he took all the punchlines and happened to be standing next to another guy. Beat Kiyoshi could never get much of a word in edgewise against Beat Takeshi’s rapid-fire onslaught of ridiculous statements, only eking out semantically-empty obvious statements as set-up, unacknowledged rhetorical questions, and ignored chastisements. He didn’t do nothing, though. He pulled big faces with bugged-out eyes, restlessly moving around from one foot to the other, getting increasingly frustrated, expressively playing the part of the audience like a horror game streamer with a facecam. He was always reacting.

The other important thing to note about The Two Beats for my purposes is that they were, reportedly, edgy. They needled society in some manner and rode controversy over their offensiveness to greater fame. 1986 was a big year for Beat Takeshi in that department, too. In December — right around the same time his video game was being released — a tabloid magazine called Friday published something about him having an affair with a college student. Angry, he got together with 11 members of his “Gundan” group of hangers-on and broke into their offices after hours to vandalize it, spray fire extinguishers around, and ultimately get arrested. It’s not clear to me if he did actual jail time for this or just got banned from TV, but regardless, they made episodes of Takeshi’s Castle with a big paper-mache Takeshi head for a while and then held a poll to see if they should bring him back that revealed that that after this whole scandal he was more popular than ever. Takeshi Kitano has remained a prickly curmudgeon in interviews his whole life, someone with perhaps a slight conservative bent who doesn’t like modern society, its phoniness and its media and its technology… such as, famously, video games.

------ MUSICAL INTERMISSION: Killdozer - Hamburger Martyr [1986] -------

Takeshi’s Challenge [1986] was not actually made by Takeshi Kitano, though, despite the title and the way people talk about it. We humans like to think of artworks as having authors regardless of how accurate a proposition that is or isn’t, largely in my view as a way of anthropomorphizing artworks because it’s awkward to speak or even think of inert objects as having intentions and acting on the world. The authorship function here is being absorbed by the celebrity tie-in branding; we want to believe that Takeshi left his fingerprints on the work as the driving auteur. The concept of the celebrity auteur game designer, contrary to belief that it is a recent development, was already well-established by 1986 and Beat Takeshi is being slotted into that archetype.

The legend goes that Kitano found out there was to be a licensed game based on himself, injected himself into the process, got super drunk over one long night, came up with all the ideas for the whole game, and the programmers dutifully took notes on every ridiculous thing he said and tried their darndest to implement it all. The original public source for this tale is the first episode of GameCenter CX [2003-2022], where it is a rumor proffered by an employee who was entirely unrelated to producing Takeshi’s Challenge, and he does say it was multiple nights unless that was a translation error. I also have heard second-hand that Takeshi himself claims to have done it over one dinner but stone-cold sober, though I don’t know the source for that claim at all. Indeed, I can’t surface any instance of Takeshi Kitano talking about this game ever at all, at least in English. I can’t even find direct support for the commonly-circulated claim that he hates video games (which I deployed right before the musical intermission,) which seems to be a key part of this whole creation myth, but which sits weirdly up against the keen-eyed enthusiasm with the novelty of Super Mario Bros implied by the design of Takeshi’s Castle. Although I did find him saying “I hate anime, and Hayao Miyazaki most of all,” for whatever that’s worth to you.

Implementation of ideas does not simply happen, and details that Takeshi Kitano could scarcely have come up with himself over dinner matter. Takeshi’s Challenge is obviously not the work of a first-time outsider to the video game form taking their first swing at it. The bulk of the game was actually made by anonymous designers and programmers at Taito, the company that brought us Space Invaders [1978] and a gaggle of other acclaimed classics clear up through and beyond 1986. It is professionally crafted, with no more in the way of bugs than Super Mario Bros, and its design shows a fairly sophisticated knowledge of video gaming as it has hitherto existed in the 80s. My best guess is that Takeshi came up with some broad strokes and the most off-the-wall bits, and the rest was made by a team that knew video games well and realized the most suitable schema at-hand in which to coherently contain those ideas was the adventure game.

A good point of comparison for Takeshi’s Challenge is The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy [1984]. They’re both high-profile collaborations with a creative celebrity author figure and industry insiders. They’re both adventure games with a notably open structure that find their own heightened and frustrating obtuseness fun and funny. They keep the punchlines to themselves but invite the player to be the frustrated comedy partner reacting to their onslaught of nonsense.

However, Hitchhiker’s is made with love for adventure games… while Takeshi’s Challenge seems to boil with something like hatred for the player, itself, and games that resemble itself. Takeshi’s Challenge is a cornerstone example in the world of “bad games.” It fits strangely in with its companions, because most infamous bad games get that regard through some kind of failure of implementation. Takeshi’s Challenge, by contrast, is an unambigious unqualified success on its own terms. It’s just that those terms are alien, grotesque, and hostile. It’s tweaking the nose of video games as an established medium, riffing on conventions, and its understanding of what it thinks “normal” video games are can be partially reverse-engineered. It is a funhouse mirror portrait of a genre I hold dear in a diseased, deranged, and almost necrotic state. It is an indictment.

Let’s review a history of adventure games in Japan. It starts with Mystery House [1980] because the focus on big pictures and minimal text made it easier to translate. (More specifically, it starts with a Japanese clone called Mystery House 1 [1982].) This is unfortunate, because Mystery House is a terrible game. Its parser is lousy, its world and story is incoherent, and half of the things the player does don’t really make sense even after you do them, nevermind reasoning things out beforehand! It’s hard to imagine that translating to another language improves this condition.

By the time we get to The Portopia Serial Murder Case [1983/1985], the manual explicitly and directly tells the player that they are going to have to systematically brute force solutions to progress sometimes. This is plainly just the expectation people have for how these types of games work, and it’s certainly not exclusive to Japan. It’s not brute force 100% of the time, but often in Portopia you gotta do everything you can everywhere you can do it, and then do it AGAIN multiple times in case you need to do it multiple times for it to have any effect at all, and AGAIN every time you accomplish anything on the off chance it might have silently advanced the game state one tick forward. Or sometimes, when you don’t have any reason to think you’ve accomplished anything because there’s no feedback. Slowly, you gather information and produce an idea of the optimal run through, learning from failures as late as the last frame of the game and gladly reloading from scratch. “Save scumming” is fully expected. You don’t just need to learn to play like this, you need to learn to LIKE doing this.

There’s a shift away from this sort of design for large games just now beginning in the late 80s, with Japanese adventure games in particular just about to take as hard a pivot away from this sort of thing as can be imagined. I believe this creates for the moment a bit of a generation gap between the adult designers of games for the Famicom/NES and their still-in-childhood players, leaving this an era of transitional pubescence that means the likes of Castlevania 2: Simon’s Quest [1987], a game that strongly resembles Takeshi’s Challenge at least on a surface level, will not “age well”. (Sarcastic quote marks because I hate that thinking.) But it’s this design paradigm that Takeshi’s Challenge sees and extends to absurd lengths.

There’s actually a rocky escalation from a pretty normal baseline of confusion to batshit bullshit. A good example of reasonably-traditional design of an adventure game puzzle is the one involving the shamisen (a Japanese musical instrument kinda like a banjo.) Towards the end of the game, once you’ve passed through two and a half one-way gates that you need to optimize your run around, you need to play the shamisen to convince someone not to kill you. You’re given 5 choices and that’s the only one that works. It also requires a two-step process in the early game to get and learn to use, which makes it look more signifigant for appearing in two menus, but then again, all of that also goes for the shakuhachi (a Japanese musical instrument kinda like a flute,) but then again, you can bring both and reload to try them one after the other. It’s still trial-and-error where you have to return back to the beginning if you’re not luckily prepared for, but it’s not total guesswork because you have an enumerated list of everything to try. This stuff isn’t a nose-tweak, it’s just normal game stuff.

It’s not just the shakuhachi, this game is actually mostly red herring by weight. The first half of the game is the part that often gets it comparisons to the 3D Grand Theft Autos, because what you do is wander aimlessly and behave more badly than you could get away with in real life though the down-to-earth setting of urban city that serves as a comedic foil for jokey signs, vulgar people, and comically incongruous but extremely video gamey violence with gangsters and cops. There’s tons of things to do and places to be, but most of it is completely irrelevant to the critical path and exists for flavor, like the candy store or barber shop. They exist seemingly mainly for the sake of their own existence, to flesh things out into a better approximation of a real city center. They also mean that you can play Takeshi’s Challenge just by poking around and existing in its space for a while instead of doing anything to progress.

But there is a plot to this game, a narrow path to follow to the end of the game. At the beginning, your boss is chewing you out for not performing well at your job, and you are absolutely not on a mission to perform better as a salaryman. While technically you shouldn’t quit right away for optimization reasons, the whole game to follow has big “freshly unemployed and at loose ends” energy. To progress, the player character has to become a complete derelict, divorcing his wife and closing out his bank account and quitting his job and leaving his kids behind, and a loud drunken hooligan regularly making such an ass of himself that he incites bar brawls. At least he pays his alimony and gets himself some adult education at the culture center. Otherwise, you’re consistently encouraged to command him to act anti-socially. There’s literally no mechanical reason not to set his speech to “threatening” at all times because that’s how you get most of the in-game hints. Binge-drinking tequila heals his. It’s progression-vital to impotently wail at pachinko to annoy people and thereby attract them in to kill ’em and steal their stuff, like a siren but more pathetic.

Unless there’s something in the manual (which is likely,) it’s only the two-time reoccurence of a treasure map in the bookstore and pachinko parlor menus that clues you in to your eventual goal. Getting this map is where the game really shows its teeth for the first time. I’ll fully outline the process: You have to do karaoke, but if you try, you are told that the machine is broken. You’re not to fix it, though. You are to do the causally unrelated action of getting a little drunk off two drinks at the bar before you will be invited to do karaoke. Then, you need to select one of five particular possible songs. You can figure out which song it is by talking to random people anywhere in town, and they’ll sing it. But not only do you need to pick the song, you need to nail it. In real life, to the game’s satisfaction. You have to sing it into the Famicom microphone on the controller, and even the microphone-free alternative which seems like a debugging tool is finicky. But not only do you need to nail the song, you need to nail it three times in a row. Nothing at all suggests this course of behavior, just sheer bloody-minded determination about how this song seems significant. Once you do that, you’ll summon a bunch of yakuza to beat down. Do that and an old man with a robe and long mustache will give you a treasure map that is blank. You have a few options for what to do with it, and some options instantly fail. Oh, and by the way, when you do fail at revealing the treasure map, the earliest you can rewind to with the password save system brings you all the way back to the very beginning of this sequence to do it all over again. But it’s not as simple as just trying every option. You also have to wait. There’s two viable options: #1, you can soak the paper in water, wait more than 5 minutes but less than 10, then shout at it through the microphone to clear it up. How are you supposed to figure out the timing without a guide? Why does shouting at paper dry it up? Beats me. You just gotta be psychic. Or, #2, you have to expose it to the sun and then wait a real-life hour without touching the controller. Your only hint to do this is that you don’t immediately fail, but if you press any button, at which point you get a failure message where the old man chastises you for wasting your chance. Same thing happens if you choose to merely stare at the map, but without the possibility of success. Once you have revealed the treasure map, you must kill the old man who gave it to you, otherwise he will show up at the very end of the game having used the map to beat you to the treasure. I’ve seen that part get flack, but it’s honestly the easiest thing to figure out what to do next about out of this whole entire sequence.

That’s not a fucking puzzle! That’s absolute god damn nonsense! It’s not even something you can brute force, it’s just so open-ended and arbitrary! I’m not even sure how the person who figured out that’s what you have to do and passed it down to us figured it out. And yet… and yet… go read a strategy guide for Tower Of Druaga [1984] or read the way Jason Dyer beat Time Zone [1982]. This sort of rigamarole was barely exaggerating the way games around it actually were, and Takeshi’s Challenge thinks that’s miserable and ridiculous. Takeshi’s Challenge isn’t setting up quite-difficult-but-surmountable challenges, it quite seriously wants you to not to persist but to give up and stop playing. When you beat it, a tiny little floating Takeshi Kitano head tells you:

"YOU ACTUALLY BOTHERED TO FINISH THIS CRAPPY GAME? SUCKER. DON'T TAKE IT SO SERIOUSLY."

And it’s snotty, but he’s right. If you played this game without a guide it must have been a full-time job for you. Even with a guide it’s many stupid hours. Getting the map’s not even the hardest part of the game, it’s just the bottleneck. There’s the infamous hang-gliding, where you have to dodge and shoot birds while not being able to move up for 2 and a half minutes. It’s not actually that hard — it’s an easier side-scrolling shooter section than Gradius [1985] or Taito’s own Darius [1987]. But it’s a totally different kind of game difficulty, going from a test of persistence to one of reflexes. I suppose that’s what makes it Takeshi’s Challenge and not Takeshi’s Patience Test. It’s almost a tautology that any hard swap from one mode of gameplay to another is a sudden switch-up of required player skills, and you’re going to filter out players who are good at the main mode of gameplay and not the other type. Here that’s exactly what Takeshi’s Challenge wants, but other developers who do this will think they’ll somehow attract both types of players by doing it. Believe me, this kind of thing is gonna be all over the likes of Manhunter: New York [1988].

The grand finale manages to ESCALATE on the level of inscrutability of the map quest. You have to essentially comb through 3 large caves pixel hunting for random completely unsignalled hotspots and then duck there to get to the next lower level. While you do that, you’re gonna be constantly swarmed by beasties. This part is even more Tower Of Druaga. It’s undoubtedly expected that you use a guide or some other community resource to get through here, but either somebody has to have actually done it the hard way at some point, unless the creators themselves told people how to do it. Famously, though this doesn’t tell us about how it was made one way or the other, the original strategy guide for this game was incomplete and had to be republished.

Here in the back half of the game, where you’re actually embarking on the treasure hunt, the game turns from a goofy version of daily life more and more into a video game-ass video game. You cross a threshold into a fantasyland, first passing through a brief waystation of tourist amenities that rub in the well-trod manicured artificiality of your journey and its destination. In fact, if you haven’t completely divested your player character of attachments and obligations to the everyday world, you will get forcibly dragged back into it and lose the game after the hang glider segment. The plot to this game is actually itself a bit of an allegory for turning your back on real life to disappear into a video game. You’re not just a derelict of your responsibilities and a piece of shit, but you’re doing it to go seek a place where platforming and violence and optimization actually matters, where there’s fake buried treasure to be found at the end of the rainbow.

Dedicating the only two buttons you get to “jump” and “attack” were, in the first half, essentially a diffuse joke about how those aren’t things that you do very often in real life but do constantly in a video game, where situations like being attacked by like 5 yakuza members and fighting them all off have to be transparently manufactured. Now, those once-odd manufactured situations are normalized to the point where you legitimately gotta use the trick where you despawn every enemy on screen by checking your inventory just to get by. You’re getting attacked by snakes and armadillos and monkeys dropping coconuts from above. You have to jump to get to places you need to be. All of a sudden, the game looks less like an adventure game and more like Adventure Island [1986]. The timeline works out such that it might literally be a parody of Adventure Island specifically, since both it and the back half of Takeshi’s Challenge both take place on fictional islands in the South Pacific.

One thing I’m downright shocked that I’ve never heard anyone say, probably because so few people make it very far into the end game, is that the back half of Takeshi’s Challenge is obviously racist. On the tourist island, the hostile mobs you learn to recognize as inherently violent on sight aren’t wearing blue-and-green costumes but instead are the only ones in the whole game that are brown-skinned. The island with the treasure is heartily littered with classic ooga-booga tribal caricatures: bones in the noses, big cannibal cooking pot, grass skirts, the works. This is extremely well-trod territory for games in the 1980s, to the point where it’s basically luck I haven’t run into quite so blatant an act of racist caricature yet. It even threatened to show up in A Mind Forever Voyaging [1985], where it doesn’t reasonably belong at all! And no, I don’t think it’s part of the parody and satire here, not that that would be an excuse but it would be something. It’s not particularly heightened or subverted or critiqued, it’s just there. Like the shamisen puzzle and such, it’s played exactly as straight and thoughtlessly as you’d find in a normal game. But just because it doesn’t mean to doesn’t mean it doesn’t still damn the grotesque ugliness of things common in video games by making itself the ugliest version.

It’s a common and intuitive thing to marry the common treasure-hunt gameplay with the classic treasure-hunt theming and plot. When we enter the back half our salaryman character even dresses up with a classic ’40s pike hat outfit just so you really know how traditionally colonialist this is about to get. You are here to steal the natives’ treasure to claim it as your own. To do so, you must first impress their spiritual and political leaders with worthless trinkets and stupid tricks in exchange for their holy item. Colonialism is such a common thing that gets circled around that I ran out of fresh things to say about how bad I think it is the last time I wrote about an infamous bad game.

So here’s the too-cute counter-reading for this one: the first half of the game is actually the more colonialist one. You, the player, are colonizing the salaryman character’s life. He’s not a blank slate, he’s got a whole life with a career and savings and a wife and kids. And then you possess him, like a demon. You destroy every way that he relates to his community: his family, his career that may give him purpose and a sense of structure and role, you even destroy pro-social behavioral norms in general. You map out his whole society and determine for him what’s worthless (books, candy, flowers, personal grooming) and what’s not (like drinking.) You plunder his life for all it’s worth, liquidating all his hard-earned assets for maximum short-term extraction, and then set him down the path of getting even more money far beyond what’s useful for him. It’s significant that the player character is a salaryman at a loan office, because the whole plot ultimately comes down not to video game metacommentary but to greed, a bottomless greed that ultimately consumes and destroys all other possible meaning there is to be found in life.

(Originally posted on my blog, Arcade Idea. I was wary to do this sort of cross-posting, because my critical style is orthogonal to the star ratings and I always feel weird about anything that smacks of self-promotion. I think some of the people I like to read here would like this, though. If my anxieties are founded and this sort of thing is not welcome here on Backloggd, please let me know!)

I see it said a lot, as basically a truism, that most or all video games are a “power fantasy.” I’ve been thinking about it and I very much disagree. There are surprisingly few games that offer up little-to-no resistance to the player enacting their will and therefore having maximal power over the game world. Rather, conventional game design is always throwing caltrops and obstacles and restrictions in front of the player. They are disempowerment fantasies, offering surmountable challenges to stimulate the player like a predator in a zoo hunting a pumpkin full of ground beef.

In Super Mario Bros, Bowser is the level designer. Takeshi Kitano cast himself as Bowser, as the villain, the bad guy in the castle. Takeshi Kitano played a lot of bad guys in movies in the 1980s (a serial killer, a cult leader, hitmen,) as his way of bucking against the unhappy confines of his newfound celebrity as a comedian and fairly ubiquitous TV light entertainment presenter type and establish himself as a serious artist, though this strategy of his would only pay off for him in the 1990s. In Takeshi’s Castle, the oppositional relationship between hero and villain is all just transparent kayfabe, it’s just for fun and really for the benefit of the hero. Really, it’s the obstacle course itself that gets to be the star of Takeshi’s Castle, it simply has more screentime than Takeshi, his castle, or any given contestant or cast member. Each anonymous contestant primarily expresses and defines their on-screen character through their relationships to the castle and how each unique approach contrasts with the ones we’ve already seen. They’re always reacting.

There’s 2 different stories of how Takeshi Kitano came by his showbiz success. There’s the short version, where it was all a fluke and he was incidentally working as a busboy and then got thrust up on stage, and the longer less-abridged version where he dedicates himself to a career in comedy through hard work and apprenticeship, deliberately working as a busboy in a particular circumstance in order to create his own luck. These stories are technically not contradictory, but they paint very different pictures and accordingly get deployed in different rhetorical circumstances. This slipperiness of mythology both allows the public character of Takeshi Kitano to be different things as the situation demands, and also suits his brand of being a multifaceted chameleon and jack-of-all-trades. It does make my life hard, though, because I’m not a very good researcher and can’t read Japanese, so the most I can do is skeptically position rumors and legends. As best as I can tell, Takeshi Kitano has written at least four autobiographies, none of which have been translated to English and most of which seem to focus on his life before fame, with various spins, such as Takeshi-Kun, Ha! [1985], which is a lighthearted children’s book about getting up to kiddie hi-jinks, or Akasuka Kid [1988], the aforementioned long version of his rise-to-fame tale, both of which got adapted to TV miniseries.

Takeshi Kitano got that start in showbiz as a “manzai” comedian in the 1970s, in the group The Two Beats (hence his nickname Beat Takeshi.) Manzai is a kind of stand-up comedy with two comedians, a funny guy and a straight man ala Abbot and Costello or a vaudeville routine or a Socratic dialogue. Usually in this sort of set-up, both participants get punchlines one way or another, but not in The Two Beats. Beat Takeshi’s routine was to be a verbal steamroller, going up there and essentially doing a solo stand-up set where he took all the punchlines and happened to be standing next to another guy. Beat Kiyoshi could never get much of a word in edgewise against Beat Takeshi’s rapid-fire onslaught of ridiculous statements, only eking out semantically-empty obvious statements as set-up, unacknowledged rhetorical questions, and ignored chastisements. He didn’t do nothing, though. He pulled big faces with bugged-out eyes, restlessly moving around from one foot to the other, getting increasingly frustrated, expressively playing the part of the audience like a horror game streamer with a facecam. He was always reacting.

The other important thing to note about The Two Beats for my purposes is that they were, reportedly, edgy. They needled society in some manner and rode controversy over their offensiveness to greater fame. 1986 was a big year for Beat Takeshi in that department, too. In December — right around the same time his video game was being released — a tabloid magazine called Friday published something about him having an affair with a college student. Angry, he got together with 11 members of his “Gundan” group of hangers-on and broke into their offices after hours to vandalize it, spray fire extinguishers around, and ultimately get arrested. It’s not clear to me if he did actual jail time for this or just got banned from TV, but regardless, they made episodes of Takeshi’s Castle with a big paper-mache Takeshi head for a while and then held a poll to see if they should bring him back that revealed that that after this whole scandal he was more popular than ever. Takeshi Kitano has remained a prickly curmudgeon in interviews his whole life, someone with perhaps a slight conservative bent who doesn’t like modern society, its phoniness and its media and its technology… such as, famously, video games.

------ MUSICAL INTERMISSION: Killdozer - Hamburger Martyr [1986] -------

Takeshi’s Challenge [1986] was not actually made by Takeshi Kitano, though, despite the title and the way people talk about it. We humans like to think of artworks as having authors regardless of how accurate a proposition that is or isn’t, largely in my view as a way of anthropomorphizing artworks because it’s awkward to speak or even think of inert objects as having intentions and acting on the world. The authorship function here is being absorbed by the celebrity tie-in branding; we want to believe that Takeshi left his fingerprints on the work as the driving auteur. The concept of the celebrity auteur game designer, contrary to belief that it is a recent development, was already well-established by 1986 and Beat Takeshi is being slotted into that archetype.

The legend goes that Kitano found out there was to be a licensed game based on himself, injected himself into the process, got super drunk over one long night, came up with all the ideas for the whole game, and the programmers dutifully took notes on every ridiculous thing he said and tried their darndest to implement it all. The original public source for this tale is the first episode of GameCenter CX [2003-2022], where it is a rumor proffered by an employee who was entirely unrelated to producing Takeshi’s Challenge, and he does say it was multiple nights unless that was a translation error. I also have heard second-hand that Takeshi himself claims to have done it over one dinner but stone-cold sober, though I don’t know the source for that claim at all. Indeed, I can’t surface any instance of Takeshi Kitano talking about this game ever at all, at least in English. I can’t even find direct support for the commonly-circulated claim that he hates video games (which I deployed right before the musical intermission,) which seems to be a key part of this whole creation myth, but which sits weirdly up against the keen-eyed enthusiasm with the novelty of Super Mario Bros implied by the design of Takeshi’s Castle. Although I did find him saying “I hate anime, and Hayao Miyazaki most of all,” for whatever that’s worth to you.

Implementation of ideas does not simply happen, and details that Takeshi Kitano could scarcely have come up with himself over dinner matter. Takeshi’s Challenge is obviously not the work of a first-time outsider to the video game form taking their first swing at it. The bulk of the game was actually made by anonymous designers and programmers at Taito, the company that brought us Space Invaders [1978] and a gaggle of other acclaimed classics clear up through and beyond 1986. It is professionally crafted, with no more in the way of bugs than Super Mario Bros, and its design shows a fairly sophisticated knowledge of video gaming as it has hitherto existed in the 80s. My best guess is that Takeshi came up with some broad strokes and the most off-the-wall bits, and the rest was made by a team that knew video games well and realized the most suitable schema at-hand in which to coherently contain those ideas was the adventure game.

A good point of comparison for Takeshi’s Challenge is The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy [1984]. They’re both high-profile collaborations with a creative celebrity author figure and industry insiders. They’re both adventure games with a notably open structure that find their own heightened and frustrating obtuseness fun and funny. They keep the punchlines to themselves but invite the player to be the frustrated comedy partner reacting to their onslaught of nonsense.

However, Hitchhiker’s is made with love for adventure games… while Takeshi’s Challenge seems to boil with something like hatred for the player, itself, and games that resemble itself. Takeshi’s Challenge is a cornerstone example in the world of “bad games.” It fits strangely in with its companions, because most infamous bad games get that regard through some kind of failure of implementation. Takeshi’s Challenge, by contrast, is an unambigious unqualified success on its own terms. It’s just that those terms are alien, grotesque, and hostile. It’s tweaking the nose of video games as an established medium, riffing on conventions, and its understanding of what it thinks “normal” video games are can be partially reverse-engineered. It is a funhouse mirror portrait of a genre I hold dear in a diseased, deranged, and almost necrotic state. It is an indictment.

Let’s review a history of adventure games in Japan. It starts with Mystery House [1980] because the focus on big pictures and minimal text made it easier to translate. (More specifically, it starts with a Japanese clone called Mystery House 1 [1982].) This is unfortunate, because Mystery House is a terrible game. Its parser is lousy, its world and story is incoherent, and half of the things the player does don’t really make sense even after you do them, nevermind reasoning things out beforehand! It’s hard to imagine that translating to another language improves this condition.

By the time we get to The Portopia Serial Murder Case [1983/1985], the manual explicitly and directly tells the player that they are going to have to systematically brute force solutions to progress sometimes. This is plainly just the expectation people have for how these types of games work, and it’s certainly not exclusive to Japan. It’s not brute force 100% of the time, but often in Portopia you gotta do everything you can everywhere you can do it, and then do it AGAIN multiple times in case you need to do it multiple times for it to have any effect at all, and AGAIN every time you accomplish anything on the off chance it might have silently advanced the game state one tick forward. Or sometimes, when you don’t have any reason to think you’ve accomplished anything because there’s no feedback. Slowly, you gather information and produce an idea of the optimal run through, learning from failures as late as the last frame of the game and gladly reloading from scratch. “Save scumming” is fully expected. You don’t just need to learn to play like this, you need to learn to LIKE doing this.

There’s a shift away from this sort of design for large games just now beginning in the late 80s, with Japanese adventure games in particular just about to take as hard a pivot away from this sort of thing as can be imagined. I believe this creates for the moment a bit of a generation gap between the adult designers of games for the Famicom/NES and their still-in-childhood players, leaving this an era of transitional pubescence that means the likes of Castlevania 2: Simon’s Quest [1987], a game that strongly resembles Takeshi’s Challenge at least on a surface level, will not “age well”. (Sarcastic quote marks because I hate that thinking.) But it’s this design paradigm that Takeshi’s Challenge sees and extends to absurd lengths.

There’s actually a rocky escalation from a pretty normal baseline of confusion to batshit bullshit. A good example of reasonably-traditional design of an adventure game puzzle is the one involving the shamisen (a Japanese musical instrument kinda like a banjo.) Towards the end of the game, once you’ve passed through two and a half one-way gates that you need to optimize your run around, you need to play the shamisen to convince someone not to kill you. You’re given 5 choices and that’s the only one that works. It also requires a two-step process in the early game to get and learn to use, which makes it look more signifigant for appearing in two menus, but then again, all of that also goes for the shakuhachi (a Japanese musical instrument kinda like a flute,) but then again, you can bring both and reload to try them one after the other. It’s still trial-and-error where you have to return back to the beginning if you’re not luckily prepared for, but it’s not total guesswork because you have an enumerated list of everything to try. This stuff isn’t a nose-tweak, it’s just normal game stuff.

It’s not just the shakuhachi, this game is actually mostly red herring by weight. The first half of the game is the part that often gets it comparisons to the 3D Grand Theft Autos, because what you do is wander aimlessly and behave more badly than you could get away with in real life though the down-to-earth setting of urban city that serves as a comedic foil for jokey signs, vulgar people, and comically incongruous but extremely video gamey violence with gangsters and cops. There’s tons of things to do and places to be, but most of it is completely irrelevant to the critical path and exists for flavor, like the candy store or barber shop. They exist seemingly mainly for the sake of their own existence, to flesh things out into a better approximation of a real city center. They also mean that you can play Takeshi’s Challenge just by poking around and existing in its space for a while instead of doing anything to progress.

But there is a plot to this game, a narrow path to follow to the end of the game. At the beginning, your boss is chewing you out for not performing well at your job, and you are absolutely not on a mission to perform better as a salaryman. While technically you shouldn’t quit right away for optimization reasons, the whole game to follow has big “freshly unemployed and at loose ends” energy. To progress, the player character has to become a complete derelict, divorcing his wife and closing out his bank account and quitting his job and leaving his kids behind, and a loud drunken hooligan regularly making such an ass of himself that he incites bar brawls. At least he pays his alimony and gets himself some adult education at the culture center. Otherwise, you’re consistently encouraged to command him to act anti-socially. There’s literally no mechanical reason not to set his speech to “threatening” at all times because that’s how you get most of the in-game hints. Binge-drinking tequila heals his. It’s progression-vital to impotently wail at pachinko to annoy people and thereby attract them in to kill ’em and steal their stuff, like a siren but more pathetic.

Unless there’s something in the manual (which is likely,) it’s only the two-time reoccurence of a treasure map in the bookstore and pachinko parlor menus that clues you in to your eventual goal. Getting this map is where the game really shows its teeth for the first time. I’ll fully outline the process: You have to do karaoke, but if you try, you are told that the machine is broken. You’re not to fix it, though. You are to do the causally unrelated action of getting a little drunk off two drinks at the bar before you will be invited to do karaoke. Then, you need to select one of five particular possible songs. You can figure out which song it is by talking to random people anywhere in town, and they’ll sing it. But not only do you need to pick the song, you need to nail it. In real life, to the game’s satisfaction. You have to sing it into the Famicom microphone on the controller, and even the microphone-free alternative which seems like a debugging tool is finicky. But not only do you need to nail the song, you need to nail it three times in a row. Nothing at all suggests this course of behavior, just sheer bloody-minded determination about how this song seems significant. Once you do that, you’ll summon a bunch of yakuza to beat down. Do that and an old man with a robe and long mustache will give you a treasure map that is blank. You have a few options for what to do with it, and some options instantly fail. Oh, and by the way, when you do fail at revealing the treasure map, the earliest you can rewind to with the password save system brings you all the way back to the very beginning of this sequence to do it all over again. But it’s not as simple as just trying every option. You also have to wait. There’s two viable options: #1, you can soak the paper in water, wait more than 5 minutes but less than 10, then shout at it through the microphone to clear it up. How are you supposed to figure out the timing without a guide? Why does shouting at paper dry it up? Beats me. You just gotta be psychic. Or, #2, you have to expose it to the sun and then wait a real-life hour without touching the controller. Your only hint to do this is that you don’t immediately fail, but if you press any button, at which point you get a failure message where the old man chastises you for wasting your chance. Same thing happens if you choose to merely stare at the map, but without the possibility of success. Once you have revealed the treasure map, you must kill the old man who gave it to you, otherwise he will show up at the very end of the game having used the map to beat you to the treasure. I’ve seen that part get flack, but it’s honestly the easiest thing to figure out what to do next about out of this whole entire sequence.

That’s not a fucking puzzle! That’s absolute god damn nonsense! It’s not even something you can brute force, it’s just so open-ended and arbitrary! I’m not even sure how the person who figured out that’s what you have to do and passed it down to us figured it out. And yet… and yet… go read a strategy guide for Tower Of Druaga [1984] or read the way Jason Dyer beat Time Zone [1982]. This sort of rigamarole was barely exaggerating the way games around it actually were, and Takeshi’s Challenge thinks that’s miserable and ridiculous. Takeshi’s Challenge isn’t setting up quite-difficult-but-surmountable challenges, it quite seriously wants you to not to persist but to give up and stop playing. When you beat it, a tiny little floating Takeshi Kitano head tells you:

"YOU ACTUALLY BOTHERED TO FINISH THIS CRAPPY GAME? SUCKER. DON'T TAKE IT SO SERIOUSLY."

And it’s snotty, but he’s right. If you played this game without a guide it must have been a full-time job for you. Even with a guide it’s many stupid hours. Getting the map’s not even the hardest part of the game, it’s just the bottleneck. There’s the infamous hang-gliding, where you have to dodge and shoot birds while not being able to move up for 2 and a half minutes. It’s not actually that hard — it’s an easier side-scrolling shooter section than Gradius [1985] or Taito’s own Darius [1987]. But it’s a totally different kind of game difficulty, going from a test of persistence to one of reflexes. I suppose that’s what makes it Takeshi’s Challenge and not Takeshi’s Patience Test. It’s almost a tautology that any hard swap from one mode of gameplay to another is a sudden switch-up of required player skills, and you’re going to filter out players who are good at the main mode of gameplay and not the other type. Here that’s exactly what Takeshi’s Challenge wants, but other developers who do this will think they’ll somehow attract both types of players by doing it. Believe me, this kind of thing is gonna be all over the likes of Manhunter: New York [1988].

The grand finale manages to ESCALATE on the level of inscrutability of the map quest. You have to essentially comb through 3 large caves pixel hunting for random completely unsignalled hotspots and then duck there to get to the next lower level. While you do that, you’re gonna be constantly swarmed by beasties. This part is even more Tower Of Druaga. It’s undoubtedly expected that you use a guide or some other community resource to get through here, but either somebody has to have actually done it the hard way at some point, unless the creators themselves told people how to do it. Famously, though this doesn’t tell us about how it was made one way or the other, the original strategy guide for this game was incomplete and had to be republished.

Here in the back half of the game, where you’re actually embarking on the treasure hunt, the game turns from a goofy version of daily life more and more into a video game-ass video game. You cross a threshold into a fantasyland, first passing through a brief waystation of tourist amenities that rub in the well-trod manicured artificiality of your journey and its destination. In fact, if you haven’t completely divested your player character of attachments and obligations to the everyday world, you will get forcibly dragged back into it and lose the game after the hang glider segment. The plot to this game is actually itself a bit of an allegory for turning your back on real life to disappear into a video game. You’re not just a derelict of your responsibilities and a piece of shit, but you’re doing it to go seek a place where platforming and violence and optimization actually matters, where there’s fake buried treasure to be found at the end of the rainbow.

Dedicating the only two buttons you get to “jump” and “attack” were, in the first half, essentially a diffuse joke about how those aren’t things that you do very often in real life but do constantly in a video game, where situations like being attacked by like 5 yakuza members and fighting them all off have to be transparently manufactured. Now, those once-odd manufactured situations are normalized to the point where you legitimately gotta use the trick where you despawn every enemy on screen by checking your inventory just to get by. You’re getting attacked by snakes and armadillos and monkeys dropping coconuts from above. You have to jump to get to places you need to be. All of a sudden, the game looks less like an adventure game and more like Adventure Island [1986]. The timeline works out such that it might literally be a parody of Adventure Island specifically, since both it and the back half of Takeshi’s Challenge both take place on fictional islands in the South Pacific.

One thing I’m downright shocked that I’ve never heard anyone say, probably because so few people make it very far into the end game, is that the back half of Takeshi’s Challenge is obviously racist. On the tourist island, the hostile mobs you learn to recognize as inherently violent on sight aren’t wearing blue-and-green costumes but instead are the only ones in the whole game that are brown-skinned. The island with the treasure is heartily littered with classic ooga-booga tribal caricatures: bones in the noses, big cannibal cooking pot, grass skirts, the works. This is extremely well-trod territory for games in the 1980s, to the point where it’s basically luck I haven’t run into quite so blatant an act of racist caricature yet. It even threatened to show up in A Mind Forever Voyaging [1985], where it doesn’t reasonably belong at all! And no, I don’t think it’s part of the parody and satire here, not that that would be an excuse but it would be something. It’s not particularly heightened or subverted or critiqued, it’s just there. Like the shamisen puzzle and such, it’s played exactly as straight and thoughtlessly as you’d find in a normal game. But just because it doesn’t mean to doesn’t mean it doesn’t still damn the grotesque ugliness of things common in video games by making itself the ugliest version.

It’s a common and intuitive thing to marry the common treasure-hunt gameplay with the classic treasure-hunt theming and plot. When we enter the back half our salaryman character even dresses up with a classic ’40s pike hat outfit just so you really know how traditionally colonialist this is about to get. You are here to steal the natives’ treasure to claim it as your own. To do so, you must first impress their spiritual and political leaders with worthless trinkets and stupid tricks in exchange for their holy item. Colonialism is such a common thing that gets circled around that I ran out of fresh things to say about how bad I think it is the last time I wrote about an infamous bad game.

So here’s the too-cute counter-reading for this one: the first half of the game is actually the more colonialist one. You, the player, are colonizing the salaryman character’s life. He’s not a blank slate, he’s got a whole life with a career and savings and a wife and kids. And then you possess him, like a demon. You destroy every way that he relates to his community: his family, his career that may give him purpose and a sense of structure and role, you even destroy pro-social behavioral norms in general. You map out his whole society and determine for him what’s worthless (books, candy, flowers, personal grooming) and what’s not (like drinking.) You plunder his life for all it’s worth, liquidating all his hard-earned assets for maximum short-term extraction, and then set him down the path of getting even more money far beyond what’s useful for him. It’s significant that the player character is a salaryman at a loan office, because the whole plot ultimately comes down not to video game metacommentary but to greed, a bottomless greed that ultimately consumes and destroys all other possible meaning there is to be found in life.

(Originally posted on my blog, Arcade Idea. I was wary to do this sort of cross-posting, because my critical style is orthogonal to the star ratings and I always feel weird about anything that smacks of self-promotion. I think some of the people I like to read here would like this, though. If my anxieties are founded and this sort of thing is not welcome here on Backloggd, please let me know!)

Terrible game. Barely anything about it is functional and it's filled to the brim with half-baked ideas that only exist because Takeshi Kitano was making this game under a mindset of "Oh shit, can I really add this into a game. I'm going to do that. Cool", sort of like how I used to make video games back in High School, but then most of the mechanics in of themselves just don't make any sense whatsoever.

But then it's also strangely memorable in a way if you look beyond the game, and it's just Kitano messing with people with his often dark and insane sense of humour - pretty much where this is just one giant shitpost, and it infamously garnered a reputation as a 'Kusoge' (Japanese for 'Shit Game'). This also acts as a weird bridge between Takeshi Kitano's lighthearted and rambling comedic persona in Takeshi's Castle - to his dark and nihilistic affair with movies such as Violent Cop (1989) and Sonatine (1993).

You don't have to play this game though. Just watch Videogamedunkey's review of it instead. He covers all the bases pretty well:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZkP-dlAgrsw

But then it's also strangely memorable in a way if you look beyond the game, and it's just Kitano messing with people with his often dark and insane sense of humour - pretty much where this is just one giant shitpost, and it infamously garnered a reputation as a 'Kusoge' (Japanese for 'Shit Game'). This also acts as a weird bridge between Takeshi Kitano's lighthearted and rambling comedic persona in Takeshi's Castle - to his dark and nihilistic affair with movies such as Violent Cop (1989) and Sonatine (1993).

You don't have to play this game though. Just watch Videogamedunkey's review of it instead. He covers all the bases pretty well:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZkP-dlAgrsw

"That was shit. Get out of here."

Is this game even remotely fun to play? No. Is this game one of the most batshit insane things I've ever played? Abso-fuckin-lutely. Realistically I'd give this game a 1 star based purely on merits but the sheer wow factor of how much garbage is in this game can't be denied. Pure kusoge goodness.

Is this game even remotely fun to play? No. Is this game one of the most batshit insane things I've ever played? Abso-fuckin-lutely. Realistically I'd give this game a 1 star based purely on merits but the sheer wow factor of how much garbage is in this game can't be denied. Pure kusoge goodness.