JetSetSoul

2023

It’s not always about the game, or what you want, or whether it’s a good use of money. Sometimes Christmas is just about giving the thing that your kid wants most and then experiencing it with them.

So there are no regrets, exactly, when I knew full-well exactly what I was walking into.

Bluey: The Videogame is an undercooked sampling of fun moments from the show. You can play “keepy uppy” with a balloon or “the floor is lava,” and you can play as any of the main characters in the Heeler family, and put certain costumes on them and go to a few of the places that they go.

And that’s about it! It reminds me, not so much of licensed console videogames, but of the commercial games that would sometimes come stuffed in a cereal box or as an addition to something else — more like a promotional aside — and not quite sensible as a fully priced object.

So my daughter got what she asked for. A Bluey game that does some of the things she’s wanted a Bluey game for. But it only took a couple hours to really see it all and most of the way wasn’t a very good time.

It’s not like back in my day, back in the ‘80s…

So there are no regrets, exactly, when I knew full-well exactly what I was walking into.

Bluey: The Videogame is an undercooked sampling of fun moments from the show. You can play “keepy uppy” with a balloon or “the floor is lava,” and you can play as any of the main characters in the Heeler family, and put certain costumes on them and go to a few of the places that they go.

And that’s about it! It reminds me, not so much of licensed console videogames, but of the commercial games that would sometimes come stuffed in a cereal box or as an addition to something else — more like a promotional aside — and not quite sensible as a fully priced object.

So my daughter got what she asked for. A Bluey game that does some of the things she’s wanted a Bluey game for. But it only took a couple hours to really see it all and most of the way wasn’t a very good time.

It’s not like back in my day, back in the ‘80s…

My niece sat across from me and kept saying the same thing: so it’s not scary but that’s why it’s scary right? I think that’s the negotiation made with children here, that they will get a preparable scary moment and the game will be about the preparation for either that moment coming or how to avoid it.

I do not love this as a horror design because doing well ought to not reduce the horror — see the new Resident Evil designs which scale to how you play them and what amount of supplies and abilities you have — if you oversucceed in those games, the difficulty measures and responds to that, that’s game design. I’d like to think the horror is the reward of playing a horror game, not the avoidance of it.

All that said, it’s a perfect format for the streaming breakthrough it experienced — in that there are broken moments of time designated to sitting and waiting, lots of dead air for a streamer to fill in.

I wrote about interviewing Nolan Bushnell, the founder of Chuck E Cheese, and my perception of the games through studying lore and playing the first game on The Twin Geeks — you can find that here:

https://thetwingeeks.com/2023/11/07/five-nights-at-freddys-what-we-make-for-others-is-no-longer-ours/

Game-wise, I surprisingly find there’s even less here than with the movie, which I can better understand as entry horror that does something I like (practical effects) vs a game wherein the horror devices are based upon limiting inputs and engagements.

That is always a central design in horror, to strip away mechanics until the absence of them are what creates a central tension. I just don’t find it that interesting to play here and understand very fully why it’s a game to be watched. It’s better that way.

I do not love this as a horror design because doing well ought to not reduce the horror — see the new Resident Evil designs which scale to how you play them and what amount of supplies and abilities you have — if you oversucceed in those games, the difficulty measures and responds to that, that’s game design. I’d like to think the horror is the reward of playing a horror game, not the avoidance of it.

All that said, it’s a perfect format for the streaming breakthrough it experienced — in that there are broken moments of time designated to sitting and waiting, lots of dead air for a streamer to fill in.

I wrote about interviewing Nolan Bushnell, the founder of Chuck E Cheese, and my perception of the games through studying lore and playing the first game on The Twin Geeks — you can find that here:

https://thetwingeeks.com/2023/11/07/five-nights-at-freddys-what-we-make-for-others-is-no-longer-ours/

Game-wise, I surprisingly find there’s even less here than with the movie, which I can better understand as entry horror that does something I like (practical effects) vs a game wherein the horror devices are based upon limiting inputs and engagements.

That is always a central design in horror, to strip away mechanics until the absence of them are what creates a central tension. I just don’t find it that interesting to play here and understand very fully why it’s a game to be watched. It’s better that way.

2023

Space is a loading screen in Starfield, a very Bethesda first-person adventure about exploring the surfaces of so many stars. You are one of many versions of You, who travel these stars, in a long and paralleled timeline of space travelers and the game puts You right into that situation — it’s very funny but it takes like five minutes from being Some Space Miner until You become The Most Important Person in the Universe.

It has a lot to do with Obvlivion and Skyrim structure-wise and if you enjoy both of these games, you will enjoy this one, too, because it is deterministically, always going to be a Bethesda game, no matter it’s outsized ambitions, which you begin to understand as actually quite practical when you get into the rhythms of the game.

The rhythms of the game, for better or worse, go like this: you move between planets and loading screens, land somewhere and progress the story, side story, or resource gather, then go to another planet and do something else with that story or those resources. Eventually, you will unlock all the right tools so that the game opens up mechanically and the full expression is more clear, but that may be a dozen hours or more in, depending on which thing you are doing, and where you spend your upgrade points after doing it.

The thing is that once you do reach this point, although the game is standard Bethesda fare until then, the new things it’s doing do begin to open up. First you play something like what you have played, and then eventually, the game comes into its own — Starfield becomes Starfield here.

The developers have put so much in the game. You will not see everything. No chance. They have designed enough to keep someone here for a long time. The long game just isn’t that interesting.

Where the game peaks is late into the story and in the faction missions — here you have already come to define the new mechanics, have unlocked enough to have agency over your own story, and probably have a sufficient build and character attributes that do what you want them to do.

At its best, it’s a fairly advanced model of what Bethesda games have always done. If you do not like those games, do not bother. If you do, you’ll find the same things to like here.

There are some great times in Starfield. Moments of awe when you land on planets and just look around at what modern games can do. It’s astounding-looking and richly aesthetic. There are limitations, in that way that certain RPGs only give back what you put into them. If you put in the effort, Starfield inevitably does reward the player with a space in the stars that is all their own.

It has a lot to do with Obvlivion and Skyrim structure-wise and if you enjoy both of these games, you will enjoy this one, too, because it is deterministically, always going to be a Bethesda game, no matter it’s outsized ambitions, which you begin to understand as actually quite practical when you get into the rhythms of the game.

The rhythms of the game, for better or worse, go like this: you move between planets and loading screens, land somewhere and progress the story, side story, or resource gather, then go to another planet and do something else with that story or those resources. Eventually, you will unlock all the right tools so that the game opens up mechanically and the full expression is more clear, but that may be a dozen hours or more in, depending on which thing you are doing, and where you spend your upgrade points after doing it.

The thing is that once you do reach this point, although the game is standard Bethesda fare until then, the new things it’s doing do begin to open up. First you play something like what you have played, and then eventually, the game comes into its own — Starfield becomes Starfield here.

The developers have put so much in the game. You will not see everything. No chance. They have designed enough to keep someone here for a long time. The long game just isn’t that interesting.

Where the game peaks is late into the story and in the faction missions — here you have already come to define the new mechanics, have unlocked enough to have agency over your own story, and probably have a sufficient build and character attributes that do what you want them to do.

At its best, it’s a fairly advanced model of what Bethesda games have always done. If you do not like those games, do not bother. If you do, you’ll find the same things to like here.

There are some great times in Starfield. Moments of awe when you land on planets and just look around at what modern games can do. It’s astounding-looking and richly aesthetic. There are limitations, in that way that certain RPGs only give back what you put into them. If you put in the effort, Starfield inevitably does reward the player with a space in the stars that is all their own.

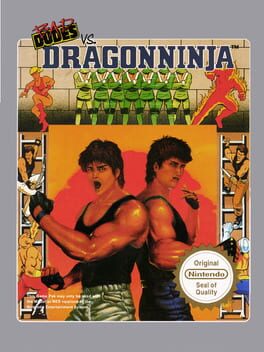

Memes used to work differently. We worked with what we had. The chunks of prescribed media that was made for us to repeat a few funny zingers and a game premise we would want to tell others about. Here comes Bad Dudes:

THE PRESIDENT HAS BEEN KIDNAPPED BY NINJAS. ARE YOU A BAD ENOUGH DUDE TO RESCUE THE PRESIDENT?

Used to be that’s all a game had to be. Hilarious longline statement: President has been captured by ninjas. Prompt for action: Are you a bad enough dude to rescue the President?

10/10 premise and execution, you don’t even need a manual, as a picture of a military looking motherfucker gives us our excellent prompt. Then we choose between two bad dudes or get to have both of them in multiplayer: BLADE AND STRIKER.

Over seven stages you move through urban Washington DC environments, from the streets to a truck level, to the sewers, to an underground lair where President Ronnie is being kept.

President Ronnie. So it was made in ‘88, but you hardly need that additional detail to know that about it. Funny thing is it’s one of those peculiar “this is America” views from the outside, more aspirationally American than interested in it’s actual culture. Or it is our only culture.

There’s an arcade game and it has chunkier weightier sprites. One of the biggest arcade games of ‘88. I say avoid it. The way this is downsized is so much more appealing. It retains arcade simplicity and then miniaturizes the parts around it, only leaving what is essential.

You punch, jump, and jump-kick your way through these seven levels and it’s tough going. You’ve gotta be a bad enough dude to use save states to save the States.

Then you get a beautifully rendered, for NES, clip of a helicopter, the White House, and you get to eat burgers with the President. Not only does Bad Dudes have the best NES setup for a premise, it also has the best conclusion.

Stone cold classic. But the game also sucks. It’s hard. The sound isn’t designed well for the platform. It’s hard to read sometimes. The mechanics aren’t as compelling or hard-hitting as the badass two-line story. The parts where you’re playing it aren’t as cool as the bookends: it doesn’t have this hyper-Americana about it, in-game, that’s just window dressing.

Still, try and find a more immediate premise than this one has, and come to realize it’s a rare exception of preferring a slightly less standout NES version to its more meaty arcade counterpart. Bonus points for being hilarious.

THE PRESIDENT HAS BEEN KIDNAPPED BY NINJAS. ARE YOU A BAD ENOUGH DUDE TO RESCUE THE PRESIDENT?

Used to be that’s all a game had to be. Hilarious longline statement: President has been captured by ninjas. Prompt for action: Are you a bad enough dude to rescue the President?

10/10 premise and execution, you don’t even need a manual, as a picture of a military looking motherfucker gives us our excellent prompt. Then we choose between two bad dudes or get to have both of them in multiplayer: BLADE AND STRIKER.

Over seven stages you move through urban Washington DC environments, from the streets to a truck level, to the sewers, to an underground lair where President Ronnie is being kept.

President Ronnie. So it was made in ‘88, but you hardly need that additional detail to know that about it. Funny thing is it’s one of those peculiar “this is America” views from the outside, more aspirationally American than interested in it’s actual culture. Or it is our only culture.

There’s an arcade game and it has chunkier weightier sprites. One of the biggest arcade games of ‘88. I say avoid it. The way this is downsized is so much more appealing. It retains arcade simplicity and then miniaturizes the parts around it, only leaving what is essential.

You punch, jump, and jump-kick your way through these seven levels and it’s tough going. You’ve gotta be a bad enough dude to use save states to save the States.

Then you get a beautifully rendered, for NES, clip of a helicopter, the White House, and you get to eat burgers with the President. Not only does Bad Dudes have the best NES setup for a premise, it also has the best conclusion.

Stone cold classic. But the game also sucks. It’s hard. The sound isn’t designed well for the platform. It’s hard to read sometimes. The mechanics aren’t as compelling or hard-hitting as the badass two-line story. The parts where you’re playing it aren’t as cool as the bookends: it doesn’t have this hyper-Americana about it, in-game, that’s just window dressing.

Still, try and find a more immediate premise than this one has, and come to realize it’s a rare exception of preferring a slightly less standout NES version to its more meaty arcade counterpart. Bonus points for being hilarious.

2023

Quietly Nintendo’s most consistent franchise, every Pikmin game is terrific, and this one may be the best and most cohesively designed of all.

As you dig further into the enhanced mechanical expression, from the excellent Dandori battles, night missions, to the retained loveliness of the Pikmin formula, this is a treat on par with anything on the Switch.

Pikmin 4 is a beautiful iteration. All new features are magnificent quality of life ideas and the expansion of what Pikmin can be, and how it functions in a game design way, feels rich and expansive.

The worlds are more interesting than ever and the cave systems are the most fun I’ve had in any new game this year. Even when a setting is just playing directly into the tried-and-true Pikmin-specific abilities, it feels so great and refined at a systems-level, that everything you do in the game simply sparks a contented kind of joy.

Savor the beautiful simplicity of the strategy systems, because this series remains the most uniquely conceived strategy game of the last couple decades.

The Dandori segments truly leverage everything good about the Pikmin mechanics and represent the functional and multi-layered progression of these mechanics over time.

Pikmin just keeps getting better. And there seems to be an open invitation for even greater iteration in Pikmin 5. There’s a perfect game to make that simply refines and totally expands all the great ideas at the heart of this game.

Pikmin is back and you’ve gotta play it. Copy that.

As you dig further into the enhanced mechanical expression, from the excellent Dandori battles, night missions, to the retained loveliness of the Pikmin formula, this is a treat on par with anything on the Switch.

Pikmin 4 is a beautiful iteration. All new features are magnificent quality of life ideas and the expansion of what Pikmin can be, and how it functions in a game design way, feels rich and expansive.

The worlds are more interesting than ever and the cave systems are the most fun I’ve had in any new game this year. Even when a setting is just playing directly into the tried-and-true Pikmin-specific abilities, it feels so great and refined at a systems-level, that everything you do in the game simply sparks a contented kind of joy.

Savor the beautiful simplicity of the strategy systems, because this series remains the most uniquely conceived strategy game of the last couple decades.

The Dandori segments truly leverage everything good about the Pikmin mechanics and represent the functional and multi-layered progression of these mechanics over time.

Pikmin just keeps getting better. And there seems to be an open invitation for even greater iteration in Pikmin 5. There’s a perfect game to make that simply refines and totally expands all the great ideas at the heart of this game.

Pikmin is back and you’ve gotta play it. Copy that.

2023

My wife bought the game, so I’ve donated to a local trans charity to absolve our family of shame and guilt.

There is a tendency in large open-world games to overdesign the spaces, to fill them with so many points of interest that the game inside the world will never utilize even half of these spaces. It’s even less in Hogwarts Legacy.

While the world of Hogwarts and its expansive surroundings is very ornate in detail and thoughtful construction, you can run through every area of the whole giant castle if you want to, you don’t want to. You don’t have a reason.

Generally missions in this massive world break down to funneling the character between conversations and usually entering a catacomb that looks like all the other catacombs in the game.

There is an initial sense we will just fast travel everywhere. Eventually you have a broom and a few creatures to traverse these spaces with, and the openness of the game becomes more open to you here, but the actual context of what you’re doing is never that interesting.

The world is dotted with Fantastic Beasts and places to find them (my daughter is hooked on the Chao Garden equivalent), trivial Merlin’s quests, and attempts at building spaces and places, none which feel as anchoring and thought-through with mechanical reasons as your starting House dorms.

There is a combat system which is more than just standard action/adventuring — the game actually tries to build a compelling spell system, where you can mix and match a big series of equipped spells, and it can be fun, building up a meter and unleashing Ancient Wizardry through a special attack.

Likewise, there is some good character stuff. Most characters exist to give you quests or to fill up spaces but a couple of your House friends are given real stories that develop and go some dark, interesting places.

There’s just enough here to get through the game but navigating the unending game spaces and really mechanically engaging with the systems is elusive. It is also, of course, a bad time to make a Hogwarts game with what the creator of these stories espouses in online vitriol — they have a disgusting presence and are failing their responsibility as a regarded curator of Fantasy with a big platform.

There is a tendency in large open-world games to overdesign the spaces, to fill them with so many points of interest that the game inside the world will never utilize even half of these spaces. It’s even less in Hogwarts Legacy.

While the world of Hogwarts and its expansive surroundings is very ornate in detail and thoughtful construction, you can run through every area of the whole giant castle if you want to, you don’t want to. You don’t have a reason.

Generally missions in this massive world break down to funneling the character between conversations and usually entering a catacomb that looks like all the other catacombs in the game.

There is an initial sense we will just fast travel everywhere. Eventually you have a broom and a few creatures to traverse these spaces with, and the openness of the game becomes more open to you here, but the actual context of what you’re doing is never that interesting.

The world is dotted with Fantastic Beasts and places to find them (my daughter is hooked on the Chao Garden equivalent), trivial Merlin’s quests, and attempts at building spaces and places, none which feel as anchoring and thought-through with mechanical reasons as your starting House dorms.

There is a combat system which is more than just standard action/adventuring — the game actually tries to build a compelling spell system, where you can mix and match a big series of equipped spells, and it can be fun, building up a meter and unleashing Ancient Wizardry through a special attack.

Likewise, there is some good character stuff. Most characters exist to give you quests or to fill up spaces but a couple of your House friends are given real stories that develop and go some dark, interesting places.

There’s just enough here to get through the game but navigating the unending game spaces and really mechanically engaging with the systems is elusive. It is also, of course, a bad time to make a Hogwarts game with what the creator of these stories espouses in online vitriol — they have a disgusting presence and are failing their responsibility as a regarded curator of Fantasy with a big platform.

2020

Persona 4 Golden is a narrative mystery game with style and depth applied to every choice along the way.

At a pure systems level, the Persona mechanics are fascinating enough. By building social links through meaningful engagement with the folks about town, you then drive forward your ability to fuse more powerful monsters significant to some central tenant of each person’s identity.

This is not only appealing on a mechanical front, as the entire narrative wraps around allotted time for the player-granted story you want to tell. Want a romantic relationship or perhaps never to talk to this person?

So, beyond mechanical layers of how Persona games work, they also feed into this visual novel choice system slotted perfectly into an RPG.

Not every moment is inspiring but so many are inspired. It’s the little things, a big accumulation of little things that begin to resemble one big story about a kid from outside town wrapped in a surreal murder mystery.

The Midnight Channel, as the wraparound thematic storytelling device, is a fascinating lens that pairs with the era just before the game in Japanese media, about appliances, technology, and translating the traditional Ghost story into the context of device culture.

That we visit these abstract dungeon crawling spaces through the access point of a television is an interesting device to create strange worlds with equally strange shadows.

Every device and element of Persona 4 Golden is reflected back unto itself. Each layer affects another layer. There is a whole depth of role-playing systems at work, which allows more nuance, if not more intrinsic focus, to popular companion RPGs, with Personas being more engaging at a system level than Pokémon, and allowing a multi-sided fight mechanic that pushes the RPG Battle Concept forward in many ways. Hard to imagine going back to anything like this game, that is not this game.

The Atlus house style is so immediately striking. The gold-black menus are beautiful and provide a thematic feeling to how the game presents itself. The jingle inside Junes plays delightfully in your mind long after the game. The audio motifs are as specialized and focused as the visual ones, and just as unique.

The visual layer, where the player moves around spaces and interacts with the game, are equally singular. It feels like a one-of-a-kind town, with memorable residents, and branching choices of what to do for work, friendship, and good old grinding. All the systems work together, even in the overworld that is largely a hub to decide what the characters do that day.

It’s a fascinating game to break apart and look at the systems inside. All of them are good and complimentary. There are peculiar choices, a couple characters with regressive messaging (especially Kanji, but occasionally everyone), and there’s that weird end point before the actual end of the game, not at all telegraphed, so you’ll need to grab a guide.

Part of these abstractions are inherent in the appeal, wherein you’re finding your way around systems and obscure personality types while trying to also solve for a puzzling murder. As a cumulative example of role-playing design across multiple levels, Persona 4 Golden is one of the best out there.

Most importantly, you’ll never forget so many of the small moments or how the game makes you feel, and it makes you feel so many things but most of all it is delightful.

At a pure systems level, the Persona mechanics are fascinating enough. By building social links through meaningful engagement with the folks about town, you then drive forward your ability to fuse more powerful monsters significant to some central tenant of each person’s identity.

This is not only appealing on a mechanical front, as the entire narrative wraps around allotted time for the player-granted story you want to tell. Want a romantic relationship or perhaps never to talk to this person?

So, beyond mechanical layers of how Persona games work, they also feed into this visual novel choice system slotted perfectly into an RPG.

Not every moment is inspiring but so many are inspired. It’s the little things, a big accumulation of little things that begin to resemble one big story about a kid from outside town wrapped in a surreal murder mystery.

The Midnight Channel, as the wraparound thematic storytelling device, is a fascinating lens that pairs with the era just before the game in Japanese media, about appliances, technology, and translating the traditional Ghost story into the context of device culture.

That we visit these abstract dungeon crawling spaces through the access point of a television is an interesting device to create strange worlds with equally strange shadows.

Every device and element of Persona 4 Golden is reflected back unto itself. Each layer affects another layer. There is a whole depth of role-playing systems at work, which allows more nuance, if not more intrinsic focus, to popular companion RPGs, with Personas being more engaging at a system level than Pokémon, and allowing a multi-sided fight mechanic that pushes the RPG Battle Concept forward in many ways. Hard to imagine going back to anything like this game, that is not this game.

The Atlus house style is so immediately striking. The gold-black menus are beautiful and provide a thematic feeling to how the game presents itself. The jingle inside Junes plays delightfully in your mind long after the game. The audio motifs are as specialized and focused as the visual ones, and just as unique.

The visual layer, where the player moves around spaces and interacts with the game, are equally singular. It feels like a one-of-a-kind town, with memorable residents, and branching choices of what to do for work, friendship, and good old grinding. All the systems work together, even in the overworld that is largely a hub to decide what the characters do that day.

It’s a fascinating game to break apart and look at the systems inside. All of them are good and complimentary. There are peculiar choices, a couple characters with regressive messaging (especially Kanji, but occasionally everyone), and there’s that weird end point before the actual end of the game, not at all telegraphed, so you’ll need to grab a guide.

Part of these abstractions are inherent in the appeal, wherein you’re finding your way around systems and obscure personality types while trying to also solve for a puzzling murder. As a cumulative example of role-playing design across multiple levels, Persona 4 Golden is one of the best out there.

Most importantly, you’ll never forget so many of the small moments or how the game makes you feel, and it makes you feel so many things but most of all it is delightful.

Every choice in designing Dark Souls is philosophical. The design choices are not typical game design choices. From Software worked like there was no roadmap to make a new game, like their history, bolstered by new ideas and depth of lore, were the only possible considerations in releasing a game against the stream of the market, that broke off and became its own tributary, sourced from a fountain of Original Influence that flowed back into games and changed everything they can be.

The first rule of Dark Souls is to unwrite these rules of games. It takes a bit of unlearning. Disengage from the systems-based, accessibility-focused ‘Quality of Life’ changes that have defined contemporary games, and discover a true link to a golden age of videogames that is more true to the medium and its possibilities than what anyone else is making.

There were so many times I gave in. When I finally embraced the game — not on my own terms and definitions of a successful play session, but on an ongoing experience of learning and meditation on the process of death — everything slid right into place.

I’m not a lore person. It does not interest me because I don’t care about the plots of modern fan service media. But Dark Souls is an exception and exceptional because it carves a lore out of so many things both inherently receivable in the design and through contextual osmosis and living in the world.

Because the game functions through constant repetition, we are then forced to consider the space. And the spaces, to my mind, are the most interesting in their linked level theory and interconnected worldbuilding, as any I’ve seen in a game.

It’s a masterclass in everything From can do. That there are so many imitations is both obvious and unfathomable. This is one of the greatest designs. Everyone should want to borrow it. This design is so specific From, nobody else will really get it right.

Any other outcome gets it wrong or tries too hard to get it right. Any process of streamlining ruins it. Any further obfuscation is… well, it would have to be intentional, because the game obtuse in such a directed way, that you cannot just do it again. You have to have the philosophy and then make the game around it.

Dark Souls raises a lot of conversations about difficulty. I can think of several moments where it goes too far. The demands of Ornstein & Smough are too rigid for the openness of the player story we tell ourselves when we play games, and especially this game. Likewise, the curses you can incur, as punishments in addition to death, feel artificial, much like a series of design choices where the prime option is really to run it through and disengage from the mechanics in an intentional way.

Likewise, the way we explore and navigate an environment is built out of intentionality. When we go on a run, if we’ve banked our points, reinforced our loadout, and settled our debts, does not always have to come with an expectation of winning. When you let go and let the game guide your sense of interest and discovery — something radically unique develops around it, led by player choice and expression of level design principles in that no one person will do every one thing in the same order.

Every run of one individual’s game, in fact, ought to have subtle differences. The great repetitions in these spaces of design are what convey the game’s meaning, because as we explore and iterate, we are so close to how games are made and their functional pieces, and yet every piece feels alien to game design standards, which have flattened out meaning and process in an effort to find audiences that play a game forever.

If you play and think about Dark Souls forever, and you will have to do one of those, then you have engaged beyond the interactivity of the text, which is straightforward, but deeper than many other games go.

Through extraordinary design decisions — bosses and themes out of the darkest fables — there is an altogether sense of cohesion. Even the parts that falter, stick to the philosophy of the design.

Most games would be sunk by the kind of ending spaces Dark Souls has. But it is such an odd thing, when these spaces are overfull of enemies and platforms like the Switch and those of the original releases just buckle under the weight of the code, that it produces another kind of joy. The weirder the choices the greater the squeeze, and the more compelling the player-base’s radical reinvention of the story, is.

And here we reach the final and most important point of Dark Souls’ success, it is a game where we tell our own stories that demands that we also tell them to others. If you play Dark Souls and do not talk to anyone about it, you have not completed the design for the player. It’s in implicit in the options: both to leave soapstones for messages and co-op, and the many hidden features and deep buried lore that rewards endless hours of investment.

Finally a game captures something like what the original Zelda did, where you just have to talk about it to understand how others approached it, and better understand yourself, but also that preliminary world of videogames to which this is the truest successor.

This is a classic to hold in the same regard as anything that has shaped the history of games. From the heights of the game and the terrific world designs of both the anti-game spaces and the very gamey ones, to the highly polished and included DLC spaces, all of it stays with you. And all of it has to be discussed.

When you fully invest in Dark Souls, you are being completely intentional about your relationship to how you play games. It can tell you so much more about yourself and what you think of it, also speaks to what you value and how you think about games.

All this makes it one of the greatest games I’ve played.

The first rule of Dark Souls is to unwrite these rules of games. It takes a bit of unlearning. Disengage from the systems-based, accessibility-focused ‘Quality of Life’ changes that have defined contemporary games, and discover a true link to a golden age of videogames that is more true to the medium and its possibilities than what anyone else is making.

There were so many times I gave in. When I finally embraced the game — not on my own terms and definitions of a successful play session, but on an ongoing experience of learning and meditation on the process of death — everything slid right into place.

I’m not a lore person. It does not interest me because I don’t care about the plots of modern fan service media. But Dark Souls is an exception and exceptional because it carves a lore out of so many things both inherently receivable in the design and through contextual osmosis and living in the world.

Because the game functions through constant repetition, we are then forced to consider the space. And the spaces, to my mind, are the most interesting in their linked level theory and interconnected worldbuilding, as any I’ve seen in a game.

It’s a masterclass in everything From can do. That there are so many imitations is both obvious and unfathomable. This is one of the greatest designs. Everyone should want to borrow it. This design is so specific From, nobody else will really get it right.

Any other outcome gets it wrong or tries too hard to get it right. Any process of streamlining ruins it. Any further obfuscation is… well, it would have to be intentional, because the game obtuse in such a directed way, that you cannot just do it again. You have to have the philosophy and then make the game around it.

Dark Souls raises a lot of conversations about difficulty. I can think of several moments where it goes too far. The demands of Ornstein & Smough are too rigid for the openness of the player story we tell ourselves when we play games, and especially this game. Likewise, the curses you can incur, as punishments in addition to death, feel artificial, much like a series of design choices where the prime option is really to run it through and disengage from the mechanics in an intentional way.

Likewise, the way we explore and navigate an environment is built out of intentionality. When we go on a run, if we’ve banked our points, reinforced our loadout, and settled our debts, does not always have to come with an expectation of winning. When you let go and let the game guide your sense of interest and discovery — something radically unique develops around it, led by player choice and expression of level design principles in that no one person will do every one thing in the same order.

Every run of one individual’s game, in fact, ought to have subtle differences. The great repetitions in these spaces of design are what convey the game’s meaning, because as we explore and iterate, we are so close to how games are made and their functional pieces, and yet every piece feels alien to game design standards, which have flattened out meaning and process in an effort to find audiences that play a game forever.

If you play and think about Dark Souls forever, and you will have to do one of those, then you have engaged beyond the interactivity of the text, which is straightforward, but deeper than many other games go.

Through extraordinary design decisions — bosses and themes out of the darkest fables — there is an altogether sense of cohesion. Even the parts that falter, stick to the philosophy of the design.

Most games would be sunk by the kind of ending spaces Dark Souls has. But it is such an odd thing, when these spaces are overfull of enemies and platforms like the Switch and those of the original releases just buckle under the weight of the code, that it produces another kind of joy. The weirder the choices the greater the squeeze, and the more compelling the player-base’s radical reinvention of the story, is.

And here we reach the final and most important point of Dark Souls’ success, it is a game where we tell our own stories that demands that we also tell them to others. If you play Dark Souls and do not talk to anyone about it, you have not completed the design for the player. It’s in implicit in the options: both to leave soapstones for messages and co-op, and the many hidden features and deep buried lore that rewards endless hours of investment.

Finally a game captures something like what the original Zelda did, where you just have to talk about it to understand how others approached it, and better understand yourself, but also that preliminary world of videogames to which this is the truest successor.

This is a classic to hold in the same regard as anything that has shaped the history of games. From the heights of the game and the terrific world designs of both the anti-game spaces and the very gamey ones, to the highly polished and included DLC spaces, all of it stays with you. And all of it has to be discussed.

When you fully invest in Dark Souls, you are being completely intentional about your relationship to how you play games. It can tell you so much more about yourself and what you think of it, also speaks to what you value and how you think about games.

All this makes it one of the greatest games I’ve played.

2020

When remaking a game, the original text doesn’t have to be sacred. Resident Evil 3, after all, is not a sacred text. To expand and take new avenues and then release as a full new game, with some cut corners is disappointing, when Resident Evil has a couple times been the standard bearer for what a Remake can be.

This is a lean action game that comes as quickly as it goes. There is not much to the survival aspect, you’ve just gotta move forward and book it most of the time and that’s also all you can do.

After the rich redesign of Resident Evil 2, which felt additive, whole sections feel as though they are missing here, and the focused action puts a fine point on how simple the game is.

It’s not without fun but it is such a passing affair that you will never think of it in league with the best survival horror, because it only has moments, and not a total wraparound design that feels like that.

It’s telling, I think, the best design in the game is when we return to the same setting as Resident Evil 2 and experience it in a new context. That is additive.

Resident Evil 3 is, admittedly, very hard to adapt. It’s so much more specific than Resident Evil and Resident Evil 2 and while they moved on to Resident Evil 4 already, which does not need to be remade but also can’t miss, Code Veronica and Zero are sitting here, with pretty good games hidden under their layers of obfuscation, where even this same approach of taking it the developer’s own way to adapt, would be more beneficial.

This is a lean action game that comes as quickly as it goes. There is not much to the survival aspect, you’ve just gotta move forward and book it most of the time and that’s also all you can do.

After the rich redesign of Resident Evil 2, which felt additive, whole sections feel as though they are missing here, and the focused action puts a fine point on how simple the game is.

It’s not without fun but it is such a passing affair that you will never think of it in league with the best survival horror, because it only has moments, and not a total wraparound design that feels like that.

It’s telling, I think, the best design in the game is when we return to the same setting as Resident Evil 2 and experience it in a new context. That is additive.

Resident Evil 3 is, admittedly, very hard to adapt. It’s so much more specific than Resident Evil and Resident Evil 2 and while they moved on to Resident Evil 4 already, which does not need to be remade but also can’t miss, Code Veronica and Zero are sitting here, with pretty good games hidden under their layers of obfuscation, where even this same approach of taking it the developer’s own way to adapt, would be more beneficial.

2019

Capcom took a good game and made a great game. This goes beyond the call of an ordinary remake, reimagining the spaces and places of Resident Evil 2 into a slickened, very modern third-person shooter that keeps all of the working ideas about the game and makes the rest that much better.

This is a terrific reimagining, even tonally changing the story and delivery to create a more reasonable and consistent throughline for the character arcs. New rooms and items have also been expanded and the way the police station, underground, sewers, and labs have been created, it feels like a consistent wraparound space, truly interconnected, and not a series of static rooms and camera angles used to create impressions of dimensions and space.

The game runs like a dream now, taking an aging and archaic system of play and modernizing it so it would be agreeable to everyone. The key is that it is still very much about preservation but the game now feels well-balanced, whether or not you have stockpiled ammo and herbs.

It sells the big moments in the best way. The bits with Mr. X are tremendous and his path finding/warping logic through the level systems, is interesting. Likewise, the design feels more organic for the player, as the interaction with the spaces is squared off and the rough edges are sanded down, then brushed with a fine coat of polish to hold all the changes it.

The game feels great and makes an old design feel immediately relevant and new. It is with the same spark that REmake entered the conversation as the best-ever Resident Evil, that RE2make now levels up the original second game to be near the front of the pack.

Some old design decisions remain, both with charm and some repetition and necessary backtracking. You still need to switch your brain into a different mode to accomplish Resident Evil puzzles, which often require running between points of interest, juggling inventory management, and bringing key items back to the right spaces. That formula doesn’t always feel compelling but it’s also tremendous that they left it untouched. That was the right thing not to modernize, and so, they did literally everything else and left the mechanical framework in place. That’s a great compromise and the right one for the developers to make.

This is a terrific reimagining, even tonally changing the story and delivery to create a more reasonable and consistent throughline for the character arcs. New rooms and items have also been expanded and the way the police station, underground, sewers, and labs have been created, it feels like a consistent wraparound space, truly interconnected, and not a series of static rooms and camera angles used to create impressions of dimensions and space.

The game runs like a dream now, taking an aging and archaic system of play and modernizing it so it would be agreeable to everyone. The key is that it is still very much about preservation but the game now feels well-balanced, whether or not you have stockpiled ammo and herbs.

It sells the big moments in the best way. The bits with Mr. X are tremendous and his path finding/warping logic through the level systems, is interesting. Likewise, the design feels more organic for the player, as the interaction with the spaces is squared off and the rough edges are sanded down, then brushed with a fine coat of polish to hold all the changes it.

The game feels great and makes an old design feel immediately relevant and new. It is with the same spark that REmake entered the conversation as the best-ever Resident Evil, that RE2make now levels up the original second game to be near the front of the pack.

Some old design decisions remain, both with charm and some repetition and necessary backtracking. You still need to switch your brain into a different mode to accomplish Resident Evil puzzles, which often require running between points of interest, juggling inventory management, and bringing key items back to the right spaces. That formula doesn’t always feel compelling but it’s also tremendous that they left it untouched. That was the right thing not to modernize, and so, they did literally everything else and left the mechanical framework in place. That’s a great compromise and the right one for the developers to make.

Surpasses the original Kingdom Battle by the tacit assertion that this scale and these mechanics make better bedfellows. It’s such a nice pairing, having learnt from the original and pared the components down, Donkey Kong Adventure meanwhile opens up the strategy and movement around fields, albeit overpowering its central characters, proving out through a new campaign and even harder challenges that less is most certainly more. There are more of the iffy puzzles, like the original, but the non skippable ones are joyous and painless, and the kind that always seemed to halt progress in the original, now feel like extra work for extra rewards, a suitable compromise. The game also just looks great — the Mario + Rabbids style even more at home in the Donkey Kong world than in the Mushroom Kingdom. Perhaps one of the finest DLCs for a Non-Nintendo developed game on a Nintendo system, this is an essential have on the Switch, ironically even more so than the original game. It ought to be sold separately.

Despite myriad graphical glitches — for two of the four worlds the level geometry was clipping wildly, often through important on-screen info — I came around on the game for two reasons: these glitches seem specific to me and once you finish the main quest, all these challenge levels open up.

I’m an X-Comer at heart. Maybe as much or far more than I’m a Mario guy, I love a good strategy game. This is a pretty stripped down version of that, simplified down to only the barest set of criteria for each little mission, sprinkled with time-wasting puzzles, and awash in a pleasing marriage between Nintendo & Ubisoft’s design sensibilities.

The cast includes Mario mainstays and some rabbits and how you compose the team and what weapons you choose are your main points of strategy. The weapons have great alliterative names and specific effects for the battlefield. There’s just enough there to create larger strategies for conflicts and in challenges, to expand the puzzle aspect of performing precise maneuvers within limited turn counts.

The game is charming and despite some crippling and possibility specific to me bugs, it kept calling me back to the experience. The world design needs a lot of work to better piece segments together and the puzzles are just sort of in the way and likewise, some small changes to the combat systems would really accentuate the way it can be fun, but this is a successful series debut and the best use of Ubisoft’s rabbits for sure.

The prospect of more DLC and a sequel is exciting, and like everything here, it just seems unlikely that more exists. I think it’s a pretty good thing and one of Ubisoft’s prouder recent moments.

I’m an X-Comer at heart. Maybe as much or far more than I’m a Mario guy, I love a good strategy game. This is a pretty stripped down version of that, simplified down to only the barest set of criteria for each little mission, sprinkled with time-wasting puzzles, and awash in a pleasing marriage between Nintendo & Ubisoft’s design sensibilities.

The cast includes Mario mainstays and some rabbits and how you compose the team and what weapons you choose are your main points of strategy. The weapons have great alliterative names and specific effects for the battlefield. There’s just enough there to create larger strategies for conflicts and in challenges, to expand the puzzle aspect of performing precise maneuvers within limited turn counts.

The game is charming and despite some crippling and possibility specific to me bugs, it kept calling me back to the experience. The world design needs a lot of work to better piece segments together and the puzzles are just sort of in the way and likewise, some small changes to the combat systems would really accentuate the way it can be fun, but this is a successful series debut and the best use of Ubisoft’s rabbits for sure.

The prospect of more DLC and a sequel is exciting, and like everything here, it just seems unlikely that more exists. I think it’s a pretty good thing and one of Ubisoft’s prouder recent moments.

2016

Doom. The name alone conjures a deep well of feelings about experiences had and what a Doom game should be. After many years without a major hit, id came out firing on all cylinders in 2016 with a BFG (Big Fucking Game), that redefined a new era of Doomer shooter, and reintroduced their brand of badass attitude-forward shooters as worthy successors of the most respected games in the whole darn genre.

You feel it right away in the Robocop-like intro, as Doomguy is brought back into this world, with an immediate context for action. Levels start very wide and horizontal, with great avenues for exploration and, surprisingly, good platforming, then as we rack up a remarkable arsenal, the game begins to funnel us down narrower paths built only for combat patterns.

We can read this design as inconsistent or as one build around our increasing context for battle. What matters is that it feels tremendous to exist in these physical spaces.

Everything you do has a fast and heavy weight to it. The new melee kills are well incorporated and feel of a part with Doom.

At best, like in the Foundry, we’re channeling Doom all the way. It’s rewarding to explore and find secrets and codex lore that is written as funny and knowing notes about the world.

The most important thing is the constant dopamine drip, how you sometimes find yourself full of absolute glee as you’re mowing down whole fields of demons, feeling both like the ultimate marine and like every action carries forward a deep-felt sense of immediacy and gravity.

There are things you don’t need to test today, like an unpopulated multiplayer and the slightly more interesting map maker. Taken just as a campaign, Doom 2016 is an extraordinary step forward that points to a radically different future for the shooter than what others were doing at the time.

Rip and tear.

You feel it right away in the Robocop-like intro, as Doomguy is brought back into this world, with an immediate context for action. Levels start very wide and horizontal, with great avenues for exploration and, surprisingly, good platforming, then as we rack up a remarkable arsenal, the game begins to funnel us down narrower paths built only for combat patterns.

We can read this design as inconsistent or as one build around our increasing context for battle. What matters is that it feels tremendous to exist in these physical spaces.

Everything you do has a fast and heavy weight to it. The new melee kills are well incorporated and feel of a part with Doom.

At best, like in the Foundry, we’re channeling Doom all the way. It’s rewarding to explore and find secrets and codex lore that is written as funny and knowing notes about the world.

The most important thing is the constant dopamine drip, how you sometimes find yourself full of absolute glee as you’re mowing down whole fields of demons, feeling both like the ultimate marine and like every action carries forward a deep-felt sense of immediacy and gravity.

There are things you don’t need to test today, like an unpopulated multiplayer and the slightly more interesting map maker. Taken just as a campaign, Doom 2016 is an extraordinary step forward that points to a radically different future for the shooter than what others were doing at the time.

Rip and tear.

Bramble is like the sister game to Brothers. Both Swedish productions, the team of Dimfrost keyed into the same joy and heavy darkness inherent in Nordic folklore as Starbreeze did with one of the best-ever stories in games, in Brothers.

Bramble can turn on a dime. It’s a beautiful thing. You might be climbing a mountain awash in beautiful moonlight then you’re down in it, wading through entrails and guts, trying to dodge the knife of a massive troll butcher. Maybe you’re being helped by a cute helpful troll or rowing along as your young boy character, with a figure of death seated right behind him, occasionally clasping his hand over the boy’s mouth, and sending him into a nightmare battle on the fringe of death.

There is a simple, pleasing linearity here. The game is not so big so as to overwhelm any of its simple story and not so small that you it doesn’t exude feeling consistently.

There is art right out of a Swedish storybook. Seriously, in comparing many images to traditional Swedish illustrations from some books, many things are pulled and recreated in the game’s own aesthetic, paintings reconfigured, old stories decontextualized.

It’s really good straightforward stuff, like Hellblade before it, exploring a culture’s stories where most of our children’s stories actually come from, but are too rarely honored in games. It’s a special game lasting only a few hours but it does a lot in a short amount of time and is full of cheer, jumps, foreboding moods, and a really pretty soundtrack.

It’s a winner and it’s short: play it on GamePass, the right space for a game like this.

Bramble can turn on a dime. It’s a beautiful thing. You might be climbing a mountain awash in beautiful moonlight then you’re down in it, wading through entrails and guts, trying to dodge the knife of a massive troll butcher. Maybe you’re being helped by a cute helpful troll or rowing along as your young boy character, with a figure of death seated right behind him, occasionally clasping his hand over the boy’s mouth, and sending him into a nightmare battle on the fringe of death.

There is a simple, pleasing linearity here. The game is not so big so as to overwhelm any of its simple story and not so small that you it doesn’t exude feeling consistently.

There is art right out of a Swedish storybook. Seriously, in comparing many images to traditional Swedish illustrations from some books, many things are pulled and recreated in the game’s own aesthetic, paintings reconfigured, old stories decontextualized.

It’s really good straightforward stuff, like Hellblade before it, exploring a culture’s stories where most of our children’s stories actually come from, but are too rarely honored in games. It’s a special game lasting only a few hours but it does a lot in a short amount of time and is full of cheer, jumps, foreboding moods, and a really pretty soundtrack.

It’s a winner and it’s short: play it on GamePass, the right space for a game like this.

2003

Vicarious Visions are GBA wizards. They made the best-ever Tony Hawk game, porting Pro Skater 2 to the GBA, so they are likely the best possible choice to translate Jet Set Radio into an isometric game of the same style.

This means dropping the two most important assets of the game — the groundbreaking cel-shaded aesthetic and crunching down the superlative soundtrack into several bite-sized looping bits.

On the whole, it’s fascinating how much has remained the same. Most of the level navigation stays true to the original game, with slight changes for the isometric perspective, one important cut level, and combining some hard-to-translate levels into smaller and more navigable spaces.

It is still hard to properly judge distances, often having to track off-screen jumps and requiring more rote memorization, while also making even more precarious choices, like shortening the allotted time in several of the game’s segments.

It has some unique features. It’s the only game where you get to play as beloved DJ Professor K. There’s four-player which I truly wish I could test or see but have no capacity for, and finishing the game unlocks some different content.

There are also several version differences between NA & PAL versions, most notably: when you finish graffiti in the PAL version, it triggers a crunchy “JET SET RADIO” effect every. single. time. In the NA version, it plays something like the original sound effect. In the PAL version, some of the character names match their original JP Dreamcast version counterpart and in the NA game, they’re consistent with versions in that market.

If the main complaint of Jet Set Radio is it’s hard to play, the isometric switch mostly intensifies that issue by making it harder to read and judge, while nullifying other factors, like making the enemies mostly useless, and not much of a threat for most of the game. It gets legitimately painful in the late levels, especially with the truncated runtimes allowed and more guesswork involved but save states exist for reasons, too.

While this is not nearly as definitive as THPS2, it’s just interesting that it exists at all. It’s a time capsule for how games used to be ported. Worth a look just out of curiosity for how everything has been shrunk down but that original Dreamcast game is still, by far, the superior option in every conceivable way.

This means dropping the two most important assets of the game — the groundbreaking cel-shaded aesthetic and crunching down the superlative soundtrack into several bite-sized looping bits.

On the whole, it’s fascinating how much has remained the same. Most of the level navigation stays true to the original game, with slight changes for the isometric perspective, one important cut level, and combining some hard-to-translate levels into smaller and more navigable spaces.

It is still hard to properly judge distances, often having to track off-screen jumps and requiring more rote memorization, while also making even more precarious choices, like shortening the allotted time in several of the game’s segments.

It has some unique features. It’s the only game where you get to play as beloved DJ Professor K. There’s four-player which I truly wish I could test or see but have no capacity for, and finishing the game unlocks some different content.

There are also several version differences between NA & PAL versions, most notably: when you finish graffiti in the PAL version, it triggers a crunchy “JET SET RADIO” effect every. single. time. In the NA version, it plays something like the original sound effect. In the PAL version, some of the character names match their original JP Dreamcast version counterpart and in the NA game, they’re consistent with versions in that market.

If the main complaint of Jet Set Radio is it’s hard to play, the isometric switch mostly intensifies that issue by making it harder to read and judge, while nullifying other factors, like making the enemies mostly useless, and not much of a threat for most of the game. It gets legitimately painful in the late levels, especially with the truncated runtimes allowed and more guesswork involved but save states exist for reasons, too.

While this is not nearly as definitive as THPS2, it’s just interesting that it exists at all. It’s a time capsule for how games used to be ported. Worth a look just out of curiosity for how everything has been shrunk down but that original Dreamcast game is still, by far, the superior option in every conceivable way.