Chwoka

63 reviews liked by Chwoka

Kickman

1981

(played the commodore 64 version because it’s joystick controlled. oh… how I would be fulfilled in life… if only I could experience a real Kickman cabinet…)

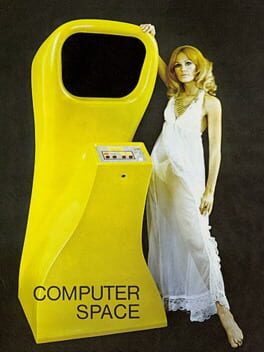

Kickman seems like a naturalization of (outdated, specific to the 80’s) gaming stereotypes. it doesn’t really “get” it and it’s not trying to. it views the arcade game as another type of carnival game—nolan bushnell quite literally thought this as well when he ripped off Spacewar!—creating no pretense of a clean break, new tradition, or legitimate artistic practice. this clumsy shortcut is naïve and clumsy and extremely funny.

because this game has no juice, and isn’t about anything, it seems to parodize the tantalizing promises of other games. consider it literally: you aren’t surviving, you aren’t controlling, you aren’t a hero. like, you’re a clown. this is who you are now. as a clown, you ride your unicycle to work, you peddle around alleyways, you do tricks on command. the kitsch disinvestment holds up a kind of exaggerated mirror on this era of arcade games.

“why do I gotta be a clown…” I think, reasonably, as if all gameplay representations are very serious and not comedic in their failures to approximate. with the city laid out before your clownship, it’s also forced into an incomprehensible stillness. civilization has parted ways, all signs of life have vanished, so the clown labors may commence. what are clown labors? well…! as we all know, the clown must feed pac-man balloons in order to maintain his claim to clownship.

arcade games are on a spectrum between determinism and indeterminacy. Kickman continues being fucking hilarious by being almost all indeterminacy. think of the game as a cross between Crane’s Kaboom! and Wozniak’s Breakout. like Kaboom!, objects (specifically balloons and pac-man effigies) fall fast, from random spots on the screen, and need to be stuck or popped (behavior determined by the round) by the player-bucket. ideally, you want to play the game like a medium-paced Kaboom! variant. the tricky part is when you “stack” things, your hitbox dynamically changes as well. there’s a lot of stuff you gotta pay attention to! it’s one of those games where you have no choice but to stare peripherally and mind-meld, you literally become the clown… except, Kickman is too baroque for that, so its random pattern will eventually be unsolvable under this paradigm of move-and-catch.

a clown is nothing without his tricks, and a Kickman is nadda without his kicks. when put into this unsolvable scenario—honk! the clown breaks from his unicycle, so, so briefly, to deliver the perfect splits. remember, he is not clownman, he is Kickman! a kicked balloon behaves like a ball hit by the Breakout paddle. these now arcing balloons can be kicked indefinitely. dropped objects are also rate-locked: if you’re kicking three things, no more will fall. this makes Kickman an agonizing pile of split-second decisions. intuitively, I wanted to pick up balloons as soon as I was able, but the arcs that kicked-balloons follow are also, essentially, random, so avoiding game over often means juggling balloons until you can collect them in a way that leads into collecting the new one which falls immediately after any collection.

as I’m trying to (successfully) believe this is a lost work of art, I’m also trying to gaslight myself into believing there’s no unwinnable scenarios in this game. the most evil thing the game can do is a split, meaning the dropping of the farthest-apart objects falling in sequence, and it happens a bit too often. I have caught splits, but it’s hard as fuck! if you’re already juggling something, and catching it causes a split to happen, well, you’re probably going to clown jail. the amount of mental-processing that has to be done at round 6 and above is beyond my ability. every time I make the right decision to keep kicking and prolong my clown-destiny, to find those synchronic cyberclown grooves, I feel like the authority on clowning around. but most of the time, I make the wrong decision. us clowns are under immense pressure in late capitalism…

when early videogames are literally about accumulation (so reminder, here it’s stacking balloons, pac-man trinkets, and uh, feeding your stacked pac-mans other balloons and trinkets), there’s a kind of primal resonance that makes me pay attention. steven poole’s landmark textual reading of Pac-Man in his book Trigger Happy alchemizes the infinite chase back into life: “For Pac-Man, consumption cannot end; no conceivable quantity of dots is enough. He will continue to search them out and eat them until he dies.”

in Kickman, this consumption not embodied by a cartoon mascot. this extension of corporate power is, instead, being forced into the entertainer’s work, it's being directed by one externally. in Kickman, the clown must work with and compete against pac-man. pac-man intrudes on his clown labors, orientating his work around him, which before (in the progression of stage 1 to stage 2) were simple balloon tricks. pac-man will eat (literally, consume) balloons that were previously integral to the clown’s work. now the entertainer works to feed pac-man. but pac-man cannot clear out other pac-mans, leading to “dead” spaces in the clownworks, where these old mascots starve, and the entertainer scrambles to make sense of this new order. this progression sounds like something… something nearby… hmm…

Kickman seems like a naturalization of (outdated, specific to the 80’s) gaming stereotypes. it doesn’t really “get” it and it’s not trying to. it views the arcade game as another type of carnival game—nolan bushnell quite literally thought this as well when he ripped off Spacewar!—creating no pretense of a clean break, new tradition, or legitimate artistic practice. this clumsy shortcut is naïve and clumsy and extremely funny.

because this game has no juice, and isn’t about anything, it seems to parodize the tantalizing promises of other games. consider it literally: you aren’t surviving, you aren’t controlling, you aren’t a hero. like, you’re a clown. this is who you are now. as a clown, you ride your unicycle to work, you peddle around alleyways, you do tricks on command. the kitsch disinvestment holds up a kind of exaggerated mirror on this era of arcade games.

“why do I gotta be a clown…” I think, reasonably, as if all gameplay representations are very serious and not comedic in their failures to approximate. with the city laid out before your clownship, it’s also forced into an incomprehensible stillness. civilization has parted ways, all signs of life have vanished, so the clown labors may commence. what are clown labors? well…! as we all know, the clown must feed pac-man balloons in order to maintain his claim to clownship.

arcade games are on a spectrum between determinism and indeterminacy. Kickman continues being fucking hilarious by being almost all indeterminacy. think of the game as a cross between Crane’s Kaboom! and Wozniak’s Breakout. like Kaboom!, objects (specifically balloons and pac-man effigies) fall fast, from random spots on the screen, and need to be stuck or popped (behavior determined by the round) by the player-bucket. ideally, you want to play the game like a medium-paced Kaboom! variant. the tricky part is when you “stack” things, your hitbox dynamically changes as well. there’s a lot of stuff you gotta pay attention to! it’s one of those games where you have no choice but to stare peripherally and mind-meld, you literally become the clown… except, Kickman is too baroque for that, so its random pattern will eventually be unsolvable under this paradigm of move-and-catch.

a clown is nothing without his tricks, and a Kickman is nadda without his kicks. when put into this unsolvable scenario—honk! the clown breaks from his unicycle, so, so briefly, to deliver the perfect splits. remember, he is not clownman, he is Kickman! a kicked balloon behaves like a ball hit by the Breakout paddle. these now arcing balloons can be kicked indefinitely. dropped objects are also rate-locked: if you’re kicking three things, no more will fall. this makes Kickman an agonizing pile of split-second decisions. intuitively, I wanted to pick up balloons as soon as I was able, but the arcs that kicked-balloons follow are also, essentially, random, so avoiding game over often means juggling balloons until you can collect them in a way that leads into collecting the new one which falls immediately after any collection.

as I’m trying to (successfully) believe this is a lost work of art, I’m also trying to gaslight myself into believing there’s no unwinnable scenarios in this game. the most evil thing the game can do is a split, meaning the dropping of the farthest-apart objects falling in sequence, and it happens a bit too often. I have caught splits, but it’s hard as fuck! if you’re already juggling something, and catching it causes a split to happen, well, you’re probably going to clown jail. the amount of mental-processing that has to be done at round 6 and above is beyond my ability. every time I make the right decision to keep kicking and prolong my clown-destiny, to find those synchronic cyberclown grooves, I feel like the authority on clowning around. but most of the time, I make the wrong decision. us clowns are under immense pressure in late capitalism…

when early videogames are literally about accumulation (so reminder, here it’s stacking balloons, pac-man trinkets, and uh, feeding your stacked pac-mans other balloons and trinkets), there’s a kind of primal resonance that makes me pay attention. steven poole’s landmark textual reading of Pac-Man in his book Trigger Happy alchemizes the infinite chase back into life: “For Pac-Man, consumption cannot end; no conceivable quantity of dots is enough. He will continue to search them out and eat them until he dies.”

in Kickman, this consumption not embodied by a cartoon mascot. this extension of corporate power is, instead, being forced into the entertainer’s work, it's being directed by one externally. in Kickman, the clown must work with and compete against pac-man. pac-man intrudes on his clown labors, orientating his work around him, which before (in the progression of stage 1 to stage 2) were simple balloon tricks. pac-man will eat (literally, consume) balloons that were previously integral to the clown’s work. now the entertainer works to feed pac-man. but pac-man cannot clear out other pac-mans, leading to “dead” spaces in the clownworks, where these old mascots starve, and the entertainer scrambles to make sense of this new order. this progression sounds like something… something nearby… hmm…

freud imagined that everything fictional or aspirational was masking a sexual desire or neurosis. someone develops some desire, probably as a child, which had to be repressed. and so, everything idealistic would be a different type of fantasy that connects to repression. a fantasy of the unknowable desire, or most often usually just a fantasy of sex, and these get funneled into a fantasy of domination. okay, I admit that’s ahistorical, he wouldn’t bring power into it, that’s for his fans and recuperators. but that’s sort of this historical throughline of the “power fantasy.” gamers and gamer-haters, does that ring a bell?

there’s something convincing (but untrue) in blanket freudian statements like… well, everything we do is because of sex, or it’s because of traumas, or it’s because of both. the lie of freudian displacement is that people are able to occupy themselves in such ways that they conceal their desires from themselves, when just as often people agonize over their desires in transparent ways. that doesn’t stop the aforementioned idea from being convincing. one thing someone said to me that stuck with me was something like, “Of course Freud’s ideas aren’t true, just like literature isn’t true. Writers choose to converse their untruth with Freud.”

seeming true is the excrement of art. some of us sickos dig through it knowingly, others do so at least unconsciously. narrative is this spindly thing, that asks to be identified, and identified with, and then in that process constitutes meaning. it’s that indeterminacy that makes me wanna chuck my draft and just say, “we are so fucked.” here I am though, wading the tides of semiotics anyway.

guys are taught semiotics from birth. in guy semiotics, behind every symbol is the same thing, “when am I going to get fucking laid?” we put on our they live glasses and it says REPRODUCE and we say, hell fucking yeah brother. this is the big time. this is what I’ve lived my entire life so far for. at least this is what every other man in my life told me that I’ve lived my whole life for. if I can’t do it, then…

I meant to focus on the unrequited, the “friend zone.” the unrequited is such a historical staple of storytelling that it is in fact unremarkable. I’m going to list nuclear examples in a second, but also imagine, the third in a romcom, the unpicked “loser” in a soap or a shoujo manga; love triangles that salaciously can’t quit, it’s the fastest way to twist the knife in any story.

the ‘fantasy’ behind canonical works of literature like The Sorrows of Young Werther or The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock—both at least one time jokingly referred to as incel-fiction—is that someone (the reader) can receive these vulnerable exigencies of masculine failure and not recoil in disgust. there is nothing unobvious to be replaced with anything else. gender fails someone, always. even for people who will continue to identify as a man, gender can only produce excess. there’s billions of gendered people and billions of ways to live. I find I can only understand gender as a heuristic that leads into convenient narratives to uphold existing forms of power.

there’s a stigma around not fucking and a stigma around getting fucked over. and the borders are porous enough that this patriarchy-derived trauma shows up in unexpected places. when I think I’m over it, it gets expressed somehow, in surprising ways. gracefully, it’s because people are accumulations. my pseudo-new patchwork will have some hollow echo of the past as it is reconstituted from the material found around me.

In the Friend Zone is a text adventure made in twine that projects a psychomap of a seemingly true freudian world. so, the church worships a phallus, the roads flow into and from a vagina. all roads lead to “it” and every person has the same desire on their lips. there’s an externalizing, otherworldly sense of heteronormative sex, while everything else is in ruins, or is nonfunctional. the nice guys that populate the friend zone have no identity, no name, only an extremely specific desire that would give meaning to everything they’ve done, alongside endless patheticism.

okay I admit it sounds kind of perfunctory and cringe when I try to summarize it. In the Friend Zone tacitly understands this, the writing leans hard away from prosaic descriptions. it’s somewhere in-between surrealist and speculative writing traditions. there’s an attention to detail in the work that makes everything occluded and hard to make out. there’s a sense that the world is only like this because I’m squinting to see it one way, so there’s also a sense that the world can’t actually be like this. it embodies a paradox of male fatalism. it takes an extreme amount of mental duress and work to maintain the tragedy of the friend zone, even though in the moment it seems like an all-encompassing, natural category of life.

perfunctory and cringe might be necessary for truth to transcend the seeming true. in other words, modern masculinity is freud for dummies. I can’t explain it without opening myself up like a loser. an atrophied part of me still holds that fear of cringe, that loserdom I lived through. my inability to treat my body like a tool, or a weapon, my inability to see my worth as a person defined by my ability to “play the game,” my inability to see a future for myself because I can’t imagine a nuclear family…

and so In the Friend Zone has another tone to its writing, it delivers forceful, rushed clunkers, almost like an exploitation film gone wrong, with sinkers like “Why did you think this would work?” and “If anyone's going to fuck [her], it's going to be me!” but the thing is, truly, actually naturalistic writing always carries some level of ‘cringe’ with it, a false derealization back into the real, which clashes with fiction’s own unnatural projection of idealism. In the Friend Zone plays around with, and sincerely delivers on its cringe, because it’s a necessary component of masculine failure. it’s these borders around embarrassment that make “being a man” natural for some people, and hopeless for others.

In the Friend Zone eventually settles as the world somehow becomes familiar. the pilgrim (the user-defined player character) gets used to text’s tonal duality and resigns themselves to the symbolic nightmare that seeps under embarrassment. and then a quest emerges, which is the search for the perfect question, the askhole that will somehow craft the magic words out of the friendzone… this game has an inventory (hence qualifying as a text adventure), though it can only be populated with souls of dead nice guys, their souls forming the aforementioned “perfect questions.” the souls kind of float around in the world like Dark Souls blood spatters. these need to be presented at the vagina shrine to get out of the friend zone (lol), though I won’t summarize what actually happens there just yet.

I think In the Friend Zone doesn’t exactly allegorize the experience of being “in the friend zone” in this second part, but it maps up the excessively obvious ideology of mainstream videogames as being a sort of a capture point, or sponge, for masculine failure and contradiction. it’s telling that the only way to progress forward is stumbling on the corpses of other nice guys. by capturing and breathing in their souls, a perfect question forms inside your lungs. the idea that male success fashions itself out other failed male bodies, rendered in summary, sounds heavy-handed. in the game, it feels helpless, paranoid, fraught.

there is a plain-spoken story within In the Friend Zone. like I noted prior, it’s exclusively expressed in the language of “cringe,” or in plain-spoken text, so it’s to be understood as an order above the nightmare, probably the actual events which created a friend zone. this is a ‘real’ love triangle, between the user-inputted object of desire and someone else named leslie. it’s unclear if the player vied for the same attentions as leslie, or if leslie is yet another alter ego externalization of the player. at one point, leslie has to relive their experience of being bullied by the highest ranking nice guy, along the fault-lines of not being masculine enough.

though multiple playthroughs of the game, I tried to piece together this ‘real’ narrative of the game, so to actually map out the love triangle, and what actually happened to leslie. this wasn’t really possible. I’m not saying it isn’t present in the game, but it’s too elliptical, and writing a youtube lore explainer would be bullshit anyway. I think this denial is more powerful than my expectation of there being a pat, complete, full answer to why, after turning on the game, I have found myself once again in the friend zone…

leslie isn’t really leslie, I guess. in a turn that I could only describe as terry pratchett-core (although still more kafkaesque than first blush, think of gregor samsa “catching a bug” and well…) they turn out to be the other person invading the friend zone, now christened as the white knight. I personally think it’s a funny turn, anyway. they’ve decided the only way to cope with the friend zone is to reform it, through violence. the complete brutality of their scenes recalls the stark, naked violence of Don Quixote, which I find to be literally an epic on masculine failure. by channeling the heroic violence of knight errantry, In the Friend Zone feels very much like, well, a videogame set up, misfiring its symbols into some felt representation of what’s going on below the surface of popular games. my earlier allusion to Dark Souls was not accidental, as I suppose the game’s allusions aren’t either.

remember, to escape the friend zone, you need to find and present the perfectly formulated questions, from corpses that are maybe yourself, or are maybe outcomes that have yet to be theorized, but branch off from this misery machine. this is the centralizing mechanic found In the Friend Zone, so it is shocking that these collectible unfutures can be spent on the only other identifiable prisoners lurking in the friend zone. when I saw the option to literally ‘spend’ my breath of life on this unhinged avatar of self-destruction, I wondered if I encountered a glitch or something. at least until I found it repeated with every other encounter with the white knight.

(I said other identifiable prisoners. well, there is also the traveler. the less said about him, the better. he’s a funny little guy, completely unsavory. he seems to purposefully have the detachment of the “manosphere” grifters. he’s in the friend zone to find marks, suckers, and specimens. In the Friend Zone imagines him trapped too, a liminal figure who is unfulfilled as well. as an abusive predator, he can’t escape the binding structure of his own lie.)

I horded my questions, naturally. even though I was trapped in the friend zone, I mean… I kind of thought I was going to get out. I’m just built differently, you know? with my huge brain, my critical thinking, my smart pose, my universal aspects that totally aren’t gendered at all, I figured out the central puzzle of the game, and mapped out the interactions between the actors. I solved the friend zone, or at least was led to believe it was something that could be mapped out and solved.

none of the questions lead out of the friend zone. none of the combinations of flags and variables will lead out, either. there’s no stereotypical secret end. there’s no code or combination out of the prison. there are actions and consequences in the friend zone, as many scenes and choices in the latter half turn out to be optional. but merely modifying the friend zone, contouring it, trying to scientifically solve or engineer it, only actualizes it more. that is the parting twist of the game, the only lingering conclusion: the friend zone isn’t other people.

this can be understood as a third order, above the ‘real’ narrative, above the embarrassing nightmare. once it’s established there’s no external way out, and the pilgrim has to make the change within himself/herself/themself, the magic circle collapses along with its ritual, and the game disappears like a mirage. we return to irl, which was just me clutching my phone in bed. as a coda, the author of the game leaves a parting message, reaching out in kindness and sympathy. maybe the future will be different…

booo! I knew that already. everyone clowns on incels because they know that ‘already,’ and the less I think about my awkward childhood the better. I’m half joking, the ending feels in conversation with the shape of desire in lots of mainstream games, and it tries to point, you know, outside of these kinds of prisons, or at least remark on an awareness of them.

after failing to alchemize some narrative climax for the pilgrim trapped in the friend zone, I remembered that I could spend my questions on other people trapped inside. this is made to be a tortuous process. the player can only ask 1 question per encounter (contrasted with the absurd outpouring of every question at once toward the romantic pedestal). the game also autosaves and has no back button. there is some hostile engineering going on here. I also get the point, as someone familiar with straight male friendships, lol. so, I get 3 total questions for the white knight, and a miserly 1 for the traveler. these questions do sketch out alternative narratives, or potentials that the friend zone makes into torture to half-realize. these questions are how I characterized the traveler in the prior parenthetical, who otherwise seems like a convenient exegesis for the narrative.

a normal player probably wouldn’t replay the game a total of 9+ times in order to make frail or nonexistent bonds with these jokey bit-players. I’m not normal, so that’s how I caught that leslie uses they/them pronouns. it’s essentially buried within the game. I think this is a stilted, but workable way to keep the focus on inherited, hegemonic trauma, rather than making it a drama about rising above the horrible bastards. this game is queer in the sense of being a game about gender failure, but it isn’t queer in the sense of representing anything inherently liberating and euphoric. this is a definition, not a value judgement.

the way I understood it, the white knight is a mechanism that can talk of or about leslie. so the white knight is fronting for leslie. what at first seems like a joke stretched to its violent end, a parody of the male feminist caught perpetually self-policing their own failure, reveals itself to be something more terminating. leslie is literally, violently trying to destroy every mirror image of their masculinity, in order to reconcile their new identity that will be now trapped in a friendless zone, being alienated from male traditions and rituals, and anxious about the potential of romantic closure because of this liminal identity. now that recognition is a painful one.

processing and talking about masculine failure, or even my inability to completely identify with masculine failure, feels like a kind of black magic. I fear conceding too much and rendering my identity submissive to the neurosis of hegemonic culture. I think gender can only become something liberating by talking through all of its contradictions and maintaining a playful self-awareness. yes, including the embarrassing stuff. but talking about gender from the male side can sometimes feel like I’m stacking negative karma, that some incel somewhere is going to personally thank me for standing up to wokeness. it is way more convenient to just never talk about it, perpetuate the stigma, and pretend it never happened.

most of the time, I drop my visor, and choose to be the white knight.

there’s something convincing (but untrue) in blanket freudian statements like… well, everything we do is because of sex, or it’s because of traumas, or it’s because of both. the lie of freudian displacement is that people are able to occupy themselves in such ways that they conceal their desires from themselves, when just as often people agonize over their desires in transparent ways. that doesn’t stop the aforementioned idea from being convincing. one thing someone said to me that stuck with me was something like, “Of course Freud’s ideas aren’t true, just like literature isn’t true. Writers choose to converse their untruth with Freud.”

seeming true is the excrement of art. some of us sickos dig through it knowingly, others do so at least unconsciously. narrative is this spindly thing, that asks to be identified, and identified with, and then in that process constitutes meaning. it’s that indeterminacy that makes me wanna chuck my draft and just say, “we are so fucked.” here I am though, wading the tides of semiotics anyway.

guys are taught semiotics from birth. in guy semiotics, behind every symbol is the same thing, “when am I going to get fucking laid?” we put on our they live glasses and it says REPRODUCE and we say, hell fucking yeah brother. this is the big time. this is what I’ve lived my entire life so far for. at least this is what every other man in my life told me that I’ve lived my whole life for. if I can’t do it, then…

I meant to focus on the unrequited, the “friend zone.” the unrequited is such a historical staple of storytelling that it is in fact unremarkable. I’m going to list nuclear examples in a second, but also imagine, the third in a romcom, the unpicked “loser” in a soap or a shoujo manga; love triangles that salaciously can’t quit, it’s the fastest way to twist the knife in any story.

the ‘fantasy’ behind canonical works of literature like The Sorrows of Young Werther or The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock—both at least one time jokingly referred to as incel-fiction—is that someone (the reader) can receive these vulnerable exigencies of masculine failure and not recoil in disgust. there is nothing unobvious to be replaced with anything else. gender fails someone, always. even for people who will continue to identify as a man, gender can only produce excess. there’s billions of gendered people and billions of ways to live. I find I can only understand gender as a heuristic that leads into convenient narratives to uphold existing forms of power.

there’s a stigma around not fucking and a stigma around getting fucked over. and the borders are porous enough that this patriarchy-derived trauma shows up in unexpected places. when I think I’m over it, it gets expressed somehow, in surprising ways. gracefully, it’s because people are accumulations. my pseudo-new patchwork will have some hollow echo of the past as it is reconstituted from the material found around me.

In the Friend Zone is a text adventure made in twine that projects a psychomap of a seemingly true freudian world. so, the church worships a phallus, the roads flow into and from a vagina. all roads lead to “it” and every person has the same desire on their lips. there’s an externalizing, otherworldly sense of heteronormative sex, while everything else is in ruins, or is nonfunctional. the nice guys that populate the friend zone have no identity, no name, only an extremely specific desire that would give meaning to everything they’ve done, alongside endless patheticism.

okay I admit it sounds kind of perfunctory and cringe when I try to summarize it. In the Friend Zone tacitly understands this, the writing leans hard away from prosaic descriptions. it’s somewhere in-between surrealist and speculative writing traditions. there’s an attention to detail in the work that makes everything occluded and hard to make out. there’s a sense that the world is only like this because I’m squinting to see it one way, so there’s also a sense that the world can’t actually be like this. it embodies a paradox of male fatalism. it takes an extreme amount of mental duress and work to maintain the tragedy of the friend zone, even though in the moment it seems like an all-encompassing, natural category of life.

perfunctory and cringe might be necessary for truth to transcend the seeming true. in other words, modern masculinity is freud for dummies. I can’t explain it without opening myself up like a loser. an atrophied part of me still holds that fear of cringe, that loserdom I lived through. my inability to treat my body like a tool, or a weapon, my inability to see my worth as a person defined by my ability to “play the game,” my inability to see a future for myself because I can’t imagine a nuclear family…

and so In the Friend Zone has another tone to its writing, it delivers forceful, rushed clunkers, almost like an exploitation film gone wrong, with sinkers like “Why did you think this would work?” and “If anyone's going to fuck [her], it's going to be me!” but the thing is, truly, actually naturalistic writing always carries some level of ‘cringe’ with it, a false derealization back into the real, which clashes with fiction’s own unnatural projection of idealism. In the Friend Zone plays around with, and sincerely delivers on its cringe, because it’s a necessary component of masculine failure. it’s these borders around embarrassment that make “being a man” natural for some people, and hopeless for others.

In the Friend Zone eventually settles as the world somehow becomes familiar. the pilgrim (the user-defined player character) gets used to text’s tonal duality and resigns themselves to the symbolic nightmare that seeps under embarrassment. and then a quest emerges, which is the search for the perfect question, the askhole that will somehow craft the magic words out of the friendzone… this game has an inventory (hence qualifying as a text adventure), though it can only be populated with souls of dead nice guys, their souls forming the aforementioned “perfect questions.” the souls kind of float around in the world like Dark Souls blood spatters. these need to be presented at the vagina shrine to get out of the friend zone (lol), though I won’t summarize what actually happens there just yet.

I think In the Friend Zone doesn’t exactly allegorize the experience of being “in the friend zone” in this second part, but it maps up the excessively obvious ideology of mainstream videogames as being a sort of a capture point, or sponge, for masculine failure and contradiction. it’s telling that the only way to progress forward is stumbling on the corpses of other nice guys. by capturing and breathing in their souls, a perfect question forms inside your lungs. the idea that male success fashions itself out other failed male bodies, rendered in summary, sounds heavy-handed. in the game, it feels helpless, paranoid, fraught.

there is a plain-spoken story within In the Friend Zone. like I noted prior, it’s exclusively expressed in the language of “cringe,” or in plain-spoken text, so it’s to be understood as an order above the nightmare, probably the actual events which created a friend zone. this is a ‘real’ love triangle, between the user-inputted object of desire and someone else named leslie. it’s unclear if the player vied for the same attentions as leslie, or if leslie is yet another alter ego externalization of the player. at one point, leslie has to relive their experience of being bullied by the highest ranking nice guy, along the fault-lines of not being masculine enough.

though multiple playthroughs of the game, I tried to piece together this ‘real’ narrative of the game, so to actually map out the love triangle, and what actually happened to leslie. this wasn’t really possible. I’m not saying it isn’t present in the game, but it’s too elliptical, and writing a youtube lore explainer would be bullshit anyway. I think this denial is more powerful than my expectation of there being a pat, complete, full answer to why, after turning on the game, I have found myself once again in the friend zone…

leslie isn’t really leslie, I guess. in a turn that I could only describe as terry pratchett-core (although still more kafkaesque than first blush, think of gregor samsa “catching a bug” and well…) they turn out to be the other person invading the friend zone, now christened as the white knight. I personally think it’s a funny turn, anyway. they’ve decided the only way to cope with the friend zone is to reform it, through violence. the complete brutality of their scenes recalls the stark, naked violence of Don Quixote, which I find to be literally an epic on masculine failure. by channeling the heroic violence of knight errantry, In the Friend Zone feels very much like, well, a videogame set up, misfiring its symbols into some felt representation of what’s going on below the surface of popular games. my earlier allusion to Dark Souls was not accidental, as I suppose the game’s allusions aren’t either.

remember, to escape the friend zone, you need to find and present the perfectly formulated questions, from corpses that are maybe yourself, or are maybe outcomes that have yet to be theorized, but branch off from this misery machine. this is the centralizing mechanic found In the Friend Zone, so it is shocking that these collectible unfutures can be spent on the only other identifiable prisoners lurking in the friend zone. when I saw the option to literally ‘spend’ my breath of life on this unhinged avatar of self-destruction, I wondered if I encountered a glitch or something. at least until I found it repeated with every other encounter with the white knight.

(I said other identifiable prisoners. well, there is also the traveler. the less said about him, the better. he’s a funny little guy, completely unsavory. he seems to purposefully have the detachment of the “manosphere” grifters. he’s in the friend zone to find marks, suckers, and specimens. In the Friend Zone imagines him trapped too, a liminal figure who is unfulfilled as well. as an abusive predator, he can’t escape the binding structure of his own lie.)

I horded my questions, naturally. even though I was trapped in the friend zone, I mean… I kind of thought I was going to get out. I’m just built differently, you know? with my huge brain, my critical thinking, my smart pose, my universal aspects that totally aren’t gendered at all, I figured out the central puzzle of the game, and mapped out the interactions between the actors. I solved the friend zone, or at least was led to believe it was something that could be mapped out and solved.

none of the questions lead out of the friend zone. none of the combinations of flags and variables will lead out, either. there’s no stereotypical secret end. there’s no code or combination out of the prison. there are actions and consequences in the friend zone, as many scenes and choices in the latter half turn out to be optional. but merely modifying the friend zone, contouring it, trying to scientifically solve or engineer it, only actualizes it more. that is the parting twist of the game, the only lingering conclusion: the friend zone isn’t other people.

this can be understood as a third order, above the ‘real’ narrative, above the embarrassing nightmare. once it’s established there’s no external way out, and the pilgrim has to make the change within himself/herself/themself, the magic circle collapses along with its ritual, and the game disappears like a mirage. we return to irl, which was just me clutching my phone in bed. as a coda, the author of the game leaves a parting message, reaching out in kindness and sympathy. maybe the future will be different…

booo! I knew that already. everyone clowns on incels because they know that ‘already,’ and the less I think about my awkward childhood the better. I’m half joking, the ending feels in conversation with the shape of desire in lots of mainstream games, and it tries to point, you know, outside of these kinds of prisons, or at least remark on an awareness of them.

after failing to alchemize some narrative climax for the pilgrim trapped in the friend zone, I remembered that I could spend my questions on other people trapped inside. this is made to be a tortuous process. the player can only ask 1 question per encounter (contrasted with the absurd outpouring of every question at once toward the romantic pedestal). the game also autosaves and has no back button. there is some hostile engineering going on here. I also get the point, as someone familiar with straight male friendships, lol. so, I get 3 total questions for the white knight, and a miserly 1 for the traveler. these questions do sketch out alternative narratives, or potentials that the friend zone makes into torture to half-realize. these questions are how I characterized the traveler in the prior parenthetical, who otherwise seems like a convenient exegesis for the narrative.

a normal player probably wouldn’t replay the game a total of 9+ times in order to make frail or nonexistent bonds with these jokey bit-players. I’m not normal, so that’s how I caught that leslie uses they/them pronouns. it’s essentially buried within the game. I think this is a stilted, but workable way to keep the focus on inherited, hegemonic trauma, rather than making it a drama about rising above the horrible bastards. this game is queer in the sense of being a game about gender failure, but it isn’t queer in the sense of representing anything inherently liberating and euphoric. this is a definition, not a value judgement.

the way I understood it, the white knight is a mechanism that can talk of or about leslie. so the white knight is fronting for leslie. what at first seems like a joke stretched to its violent end, a parody of the male feminist caught perpetually self-policing their own failure, reveals itself to be something more terminating. leslie is literally, violently trying to destroy every mirror image of their masculinity, in order to reconcile their new identity that will be now trapped in a friendless zone, being alienated from male traditions and rituals, and anxious about the potential of romantic closure because of this liminal identity. now that recognition is a painful one.

processing and talking about masculine failure, or even my inability to completely identify with masculine failure, feels like a kind of black magic. I fear conceding too much and rendering my identity submissive to the neurosis of hegemonic culture. I think gender can only become something liberating by talking through all of its contradictions and maintaining a playful self-awareness. yes, including the embarrassing stuff. but talking about gender from the male side can sometimes feel like I’m stacking negative karma, that some incel somewhere is going to personally thank me for standing up to wokeness. it is way more convenient to just never talk about it, perpetuate the stigma, and pretend it never happened.

most of the time, I drop my visor, and choose to be the white knight.

it was cool to discover Hexen as a missing link, or an inspiration, for the puzzle maps in Master Levels for Doom II or Eternal Doom (not Doom Eternal, scrubs). Hexen still feels distinct from doom because of the dark fantasy stuff. Hexen will also always flow differently than Doom because of the lack of hit-scan enemies. it never really tells me, don’t stand here, don’t walk in this way, don’t leave this guy alive. the action is less engaging in this specific sense because there are less micro-decisions to make in how each encounter is approached and literally looked at. Hexen makes up for it by the grueling complexity of its world, or arguably hits a good balance between that and its medium complex action. there’s a massive cognitive load put into that struggle for survival, while also managing my inventory, while also putting my close sight on every single possible suspicious detail. like burying carthage while battling for it or something.

it’s also a delightfully goofy game that plays around as it tests the player. it’s genuinely funny to hit a switch and watch 30 wizards float out of the walls.

I can’t say it’s painless. if, maybe, ideal puzzle design requires that you can visibly see and measure your inputs, it’s maniacal to make a puzzle game where your inputs interact with something you may or may not have seen. Hexen is the distended puzzle game, the whole world feels like a mechanical organism that shifts and stirs when I stand on its parts, or when I poke at its holes. it’s very difficult to decide if I’m going the right way, if I’ve been in specific places or not, or if I still need to be in one place or another. Hexen has a leg up (or down) by usually conforming to a logical system. the trouble is that the player never knows what logic or what system. and it still preserves the forbidden feeling, the feeling of impossible discovery, by having walls I needed to rotate or walk-through, by having invisible floating paths I needed to find and follow.

videogames absorbed fantasy in this way, they have reconstructed a generic sensibility out of a body of meditations on history and ritual. Hexen is fascinated with the mystery this presents. like a fromsoftware joint, it teases that possibility with violence. it’s a monotonous glaze toward the search for something! so this search will be painful and hard fought. because of really game designy tricks (and limitations of the doom engine) the feeling of the search is soooo embodied. I always approach fantasy from the search. I’m asking if it could be allegory, where the symbols came from, why these specific ones, what could it possibly all mean. it’s probably meaningless in Hexen, which is why the search itself set my mind afire. literally how good are you at close reading the juvenile nothings, will you find the rosetta stone, the secret pattern, they key that leads out of this obsession…

it’s also a delightfully goofy game that plays around as it tests the player. it’s genuinely funny to hit a switch and watch 30 wizards float out of the walls.

I can’t say it’s painless. if, maybe, ideal puzzle design requires that you can visibly see and measure your inputs, it’s maniacal to make a puzzle game where your inputs interact with something you may or may not have seen. Hexen is the distended puzzle game, the whole world feels like a mechanical organism that shifts and stirs when I stand on its parts, or when I poke at its holes. it’s very difficult to decide if I’m going the right way, if I’ve been in specific places or not, or if I still need to be in one place or another. Hexen has a leg up (or down) by usually conforming to a logical system. the trouble is that the player never knows what logic or what system. and it still preserves the forbidden feeling, the feeling of impossible discovery, by having walls I needed to rotate or walk-through, by having invisible floating paths I needed to find and follow.

videogames absorbed fantasy in this way, they have reconstructed a generic sensibility out of a body of meditations on history and ritual. Hexen is fascinated with the mystery this presents. like a fromsoftware joint, it teases that possibility with violence. it’s a monotonous glaze toward the search for something! so this search will be painful and hard fought. because of really game designy tricks (and limitations of the doom engine) the feeling of the search is soooo embodied. I always approach fantasy from the search. I’m asking if it could be allegory, where the symbols came from, why these specific ones, what could it possibly all mean. it’s probably meaningless in Hexen, which is why the search itself set my mind afire. literally how good are you at close reading the juvenile nothings, will you find the rosetta stone, the secret pattern, they key that leads out of this obsession…

I am pretty sure Neverending Nightmares is set in the late 1800s to give its edward gorey riff more authenticity, in the perfectly naïve way that indie games plumb this or that aesthetic in order to stand out, rather ignorant of what they’re standing in. still, the extravagant wealth portrayed in this facsimile of high living could have only been accumulated through slavery or colonialism (or of course, both). implicitly then, racism and class war drape the warped nursery that facilitates playing chicken with the protagonist’s misogynistic impulses, ones that he inevitably succumbs to in his imagination, again and again. notably, only ever in his imagination. he is fighting the ghosts of his unconscious drive, things that he inherited but does not ever quite completely understand.

if there is a coherent story, it’s only to create a non-productive, schizo-oedipal between sister/daughter/wife. it is very enjoyable to me how much the author does not understand freud, because the legacy of freud is much better mangled like this and made into worthless dead-ends. so it is interesting, then, how much the game delimits its own potential. its mechanics are ever-present, and demand some joke-like spectrum of mastery. but they do not develop really. and the game still resists being stripped down to its essential components, adding disjunctions and doodads that lead to non-linear, non-connecting zones. or more often, plain, gratuitous, horrible self-violence, as if it is the only possible response to what the protagonist has inherited. the idea of non-productive flows comes to my mind, in a way that naturally stymies and cuts off the post-Silent Hill 2 psychodrama in a way that’s a mixture of stoic deliberation and totally natural submission into a complete portrayal of impulses (also, budget constraints, lol).

and so much like this. there’s a dream sequence in The Book of Franza by ingeborg bachmann where a father points out to his daughter: “this is the cemetery of buried daughters,” and hearing this she sobs. this exchange, metaphor doubled, is charged with patriarchal violence, seeming to say, I will bury you there, or, haven’t I already? yet it’s also farcical, as the father and daughter yet live, and the implication hangs on without ever getting held on. if I’m able to step outside of jung for a moment, I can re-recognize this scene as shared grief. the position-in-relation, instead of the position-of-satisfaction. should we not mourn for the daughters? I think this counterfactual in vain, the specter of neurosis looms all around, and I don’t yet know how to forgive it.

I love many scenes in books and I don’t end up remembering them. I’ve held on to this one like a reality marble, a final projection, and I think it’s because it’s a physical place. a place you can look at and go to, one you can walk around in. this physical, dreamed up allegory of endings, is… well it’s a lot like a videogame, to me. it is, I guess, the evil version of the museum of dead wifery, one that’s to be taken at face value, instead of integrated into an ironic system. it provokes a stale romanticism, a domestic grief, a remove from the problems, as they’re used to garnish existing grief, that is converted into relation only by a selfish desire to embody the more difficult, accumulated forms of covalent suffering from this place of remove.

lots of games are like this, including Neverending Nightmares. I suppose if I had more integrity I would condemn it, if I believed art is our vehicle into a better world. cecile pineda wrote that writing can “…provide a moment of grace, both for her who writes and him who reads, in a very dark world.” her novel Face is almost a constructive case against degradation, as it refuses to be specifically one problem of degradation. and so like that book, it is a stupid, pithy fact that I relate to the honest depictions of intrusive violence in Neverending Nightmares. maybe not all of them at once, and maybe not as much anymore, but if I could discard every mistake and thoughtcrime I’ve made at once, I probably wouldn’t be writing about games anymore.

if there is a coherent story, it’s only to create a non-productive, schizo-oedipal between sister/daughter/wife. it is very enjoyable to me how much the author does not understand freud, because the legacy of freud is much better mangled like this and made into worthless dead-ends. so it is interesting, then, how much the game delimits its own potential. its mechanics are ever-present, and demand some joke-like spectrum of mastery. but they do not develop really. and the game still resists being stripped down to its essential components, adding disjunctions and doodads that lead to non-linear, non-connecting zones. or more often, plain, gratuitous, horrible self-violence, as if it is the only possible response to what the protagonist has inherited. the idea of non-productive flows comes to my mind, in a way that naturally stymies and cuts off the post-Silent Hill 2 psychodrama in a way that’s a mixture of stoic deliberation and totally natural submission into a complete portrayal of impulses (also, budget constraints, lol).

and so much like this. there’s a dream sequence in The Book of Franza by ingeborg bachmann where a father points out to his daughter: “this is the cemetery of buried daughters,” and hearing this she sobs. this exchange, metaphor doubled, is charged with patriarchal violence, seeming to say, I will bury you there, or, haven’t I already? yet it’s also farcical, as the father and daughter yet live, and the implication hangs on without ever getting held on. if I’m able to step outside of jung for a moment, I can re-recognize this scene as shared grief. the position-in-relation, instead of the position-of-satisfaction. should we not mourn for the daughters? I think this counterfactual in vain, the specter of neurosis looms all around, and I don’t yet know how to forgive it.

I love many scenes in books and I don’t end up remembering them. I’ve held on to this one like a reality marble, a final projection, and I think it’s because it’s a physical place. a place you can look at and go to, one you can walk around in. this physical, dreamed up allegory of endings, is… well it’s a lot like a videogame, to me. it is, I guess, the evil version of the museum of dead wifery, one that’s to be taken at face value, instead of integrated into an ironic system. it provokes a stale romanticism, a domestic grief, a remove from the problems, as they’re used to garnish existing grief, that is converted into relation only by a selfish desire to embody the more difficult, accumulated forms of covalent suffering from this place of remove.

lots of games are like this, including Neverending Nightmares. I suppose if I had more integrity I would condemn it, if I believed art is our vehicle into a better world. cecile pineda wrote that writing can “…provide a moment of grace, both for her who writes and him who reads, in a very dark world.” her novel Face is almost a constructive case against degradation, as it refuses to be specifically one problem of degradation. and so like that book, it is a stupid, pithy fact that I relate to the honest depictions of intrusive violence in Neverending Nightmares. maybe not all of them at once, and maybe not as much anymore, but if I could discard every mistake and thoughtcrime I’ve made at once, I probably wouldn’t be writing about games anymore.

the mascot is a disconnection from the real or natural, that creates a new solitary connection that simply relates back to itself (classic deterritorialization/reterritorialization for you sickos). there’s no cultural legacy of mario that doesn’t just relate back to mario and symbolic interpretations of nintendo. may mario relate to mario and the symbolic health to nintendo, and whatever. this is the desperation that hangs around every new mario game.

“the king is in his bedchamber. is he sick? we all wait with bated breath… unbelievable… ! IGN has given Mario Forever a perfect 10/10! the king yet lives! may his empire reign forever!”

so, every mascot is a failure. a failure to represent, to connect, to live. in the place of the straightforward identification, which has previously defined participatory storytelling, now there is a road sign. mascots point out, right out down the superhighway, leading right up to corporate headquarters. mascots draw attention to the success—or not—of the work at the expense of something emotive, something human. mascots are advertising, so the interpretive question they pose is as simple and condensed as possible. is this profitable? and you answer… maybe!

now here we have bubsy, a failure among failures. to fail at being a failure… that would imply a schoolyard double negative, you know, a success that comes from the heroic rejection of hegemony. that is definitely not the case. bubsy, the art object, not the guy, is the aesthetic personification of loser, the energy of an entrepreneur who is forced to teach because they couldn’t cut it, and hilariously they give their students the same bad advice. whatever, it’s gambling either way.

buby’s negation only twists and fucks with the process of reconnection. bubsy’s roadsign leads straight into the desert. we’re talking just deterritorialization, baby.

this is truly what’s funny about playing bubsy. it’s not a bad game. no seriously, you chucklefucks, it’s not a bad game, it’s just hard. I’m a demiurge for failures. I’m confident comparing bubsy to Superfrog, Rocky Rodent, and Zool, the rogue’s gallery of sonic-failures, and it’s the only one that makes you feel lost in a giant superstructure, it’s the only one that understands the juice behind Sonic the Hedgehog is disorientation.

designer michael berlyn claims to have played sonic 1 for 98 hours before making bubsy. I believe him, I don’t think that’s hype. bubsy is a studied intensification of that game. yes, you can’t pick up and play it. you gotta have patience with the game. take your time to explore the different routes. find the one that works for you. bubsy is not about “going fast” like a fucking generic downstream comic book videogame power fantasy, but merely having the ability. it’s one of your tools, use it or don’t. bubsy instead has a staccato-like rhythm to it, your jump feels like a triplet, always coming in controlled multiples, and there’s this percussive quality to it, as you improvise and stay in the air and figure out where this asshole is allowed to exist.

the difficulty cinches the pathetique of bubsy. he’s just not cool or heroic. I fuck with that. I’m plain sick of heroics. my favorite moment of the game is bubsy walking back on screen, after dying in a horrible, stupid way, because you can only die in horrible, stupid ways in platformers. his body looks like a corny cartoon accordion and he just quips, “what, and give up show business?”

bubsy comparing platforming to shit-shoveling briefly got me to misrecognize the game as playbor. I became aware of the electricity in my room, like one becomes aware of their breathing. it then became a little eerie to recognize bubsy’s complaints and desire to renegotiate the terms of his labor. one of bubsy’s only character traits is the fact that he’s proletarianized. he’s proletarianized and his creators and everyone just fucking hates him. what can possibly go wrong?

“the king is in his bedchamber. is he sick? we all wait with bated breath… unbelievable… ! IGN has given Mario Forever a perfect 10/10! the king yet lives! may his empire reign forever!”

so, every mascot is a failure. a failure to represent, to connect, to live. in the place of the straightforward identification, which has previously defined participatory storytelling, now there is a road sign. mascots point out, right out down the superhighway, leading right up to corporate headquarters. mascots draw attention to the success—or not—of the work at the expense of something emotive, something human. mascots are advertising, so the interpretive question they pose is as simple and condensed as possible. is this profitable? and you answer… maybe!

now here we have bubsy, a failure among failures. to fail at being a failure… that would imply a schoolyard double negative, you know, a success that comes from the heroic rejection of hegemony. that is definitely not the case. bubsy, the art object, not the guy, is the aesthetic personification of loser, the energy of an entrepreneur who is forced to teach because they couldn’t cut it, and hilariously they give their students the same bad advice. whatever, it’s gambling either way.

buby’s negation only twists and fucks with the process of reconnection. bubsy’s roadsign leads straight into the desert. we’re talking just deterritorialization, baby.

this is truly what’s funny about playing bubsy. it’s not a bad game. no seriously, you chucklefucks, it’s not a bad game, it’s just hard. I’m a demiurge for failures. I’m confident comparing bubsy to Superfrog, Rocky Rodent, and Zool, the rogue’s gallery of sonic-failures, and it’s the only one that makes you feel lost in a giant superstructure, it’s the only one that understands the juice behind Sonic the Hedgehog is disorientation.

designer michael berlyn claims to have played sonic 1 for 98 hours before making bubsy. I believe him, I don’t think that’s hype. bubsy is a studied intensification of that game. yes, you can’t pick up and play it. you gotta have patience with the game. take your time to explore the different routes. find the one that works for you. bubsy is not about “going fast” like a fucking generic downstream comic book videogame power fantasy, but merely having the ability. it’s one of your tools, use it or don’t. bubsy instead has a staccato-like rhythm to it, your jump feels like a triplet, always coming in controlled multiples, and there’s this percussive quality to it, as you improvise and stay in the air and figure out where this asshole is allowed to exist.

the difficulty cinches the pathetique of bubsy. he’s just not cool or heroic. I fuck with that. I’m plain sick of heroics. my favorite moment of the game is bubsy walking back on screen, after dying in a horrible, stupid way, because you can only die in horrible, stupid ways in platformers. his body looks like a corny cartoon accordion and he just quips, “what, and give up show business?”

bubsy comparing platforming to shit-shoveling briefly got me to misrecognize the game as playbor. I became aware of the electricity in my room, like one becomes aware of their breathing. it then became a little eerie to recognize bubsy’s complaints and desire to renegotiate the terms of his labor. one of bubsy’s only character traits is the fact that he’s proletarianized. he’s proletarianized and his creators and everyone just fucking hates him. what can possibly go wrong?

I picked this up for the nostalgia trip—I came back to it over and over again as a young child but never managed to make much headway on the riddles. As an adult, though, in addition to being endlessly charmed by the CGI/FMV hybridization, I was deeply impressed by how thoughtfully designed the game is.

The player is challenged to solve seven scientific riddles in order to satisfy a rogue AI and persuade it to divert a meteoroid before it collides with earth in five days' time. Doing so involves a point-and-click mixture of learning scientific facts and applying them to interactive puzzles, eventually yielding some object that you can submit as a riddle solution.

On the surface this is fairly standard mid-90s fare, although it's clear that the creators had a lot of fun cramming it full of goofs, science facts, and references to the Bill Nye show. But there's also a keen eye here towards the way the player approaches the game: although Nye Labs is fairly open to exploration, the puzzles are set up to gently guide you through in a particular order, gating challenges on one another or just on exploration through the space.

It's even clear that my childhood mode of play, to fail over and over again to actually stop the meteoroid, was an intended pattern. Very little in the game is mechanically off-limits. Instead, it's almost exclusively blocked by knowledge. Once you're aware of how to solve one or another riddle (or even enter the one explicitly locked area of the lab), you can do it instantly in your next session. The game expects the player to learn over time not just in terms of science but in terms of the space it creates.

The player is challenged to solve seven scientific riddles in order to satisfy a rogue AI and persuade it to divert a meteoroid before it collides with earth in five days' time. Doing so involves a point-and-click mixture of learning scientific facts and applying them to interactive puzzles, eventually yielding some object that you can submit as a riddle solution.

On the surface this is fairly standard mid-90s fare, although it's clear that the creators had a lot of fun cramming it full of goofs, science facts, and references to the Bill Nye show. But there's also a keen eye here towards the way the player approaches the game: although Nye Labs is fairly open to exploration, the puzzles are set up to gently guide you through in a particular order, gating challenges on one another or just on exploration through the space.

It's even clear that my childhood mode of play, to fail over and over again to actually stop the meteoroid, was an intended pattern. Very little in the game is mechanically off-limits. Instead, it's almost exclusively blocked by knowledge. Once you're aware of how to solve one or another riddle (or even enter the one explicitly locked area of the lab), you can do it instantly in your next session. The game expects the player to learn over time not just in terms of science but in terms of the space it creates.

I’ve spent a lot of my recent fascination with adventure games in the margins of the genre, poking around the edges of the obscure, the forgotten, and the maligned. This was true even when I was younger and had my first forays into the space with stuff like Phantasmagoria, Harvester, and Dark Seed. Not that shit like the I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream game is unknown, just less talked about then the likes of the Lucas Arts and Sierra legends. So now that I’m on a hiatus from Nancy Drew but still feeling the itch, I’m feeling around a bit. And since I thoroughly enjoyed Gabriel Knight my endless fascination with the histories, legacies, and evolutions of genres and developers and series over time of course led me back to the beginning of the company and really this era of the genre, with the original King’s Quest, which is a Cool Game, imo.

It’s very much a transitional piece between old timey text games and the modern style of adventure games that it heralds, so there’s an obvious feeling of age to it beyond the 1984 IBM graphics, which are actually super impressive (it’s fun to think that the equivalent of a AAA game dumping all their time and money into the first hour of the game because that’s all most people will play is having flags AND alligators that animate). I do think, however, that the text parser you use for all of your interactions beyond basic movement (and, frustratingly, like two other actions one time each) works really well, and all in all I didn’t have any trouble adapting to the control scheme at all.

There’s really a tug of war to the experience of playing King’s Quest 1 that define the experience as one that must have been really mind blowing compared to its contemporaries and still makes it feel unique and worthwhile today: one side is the extremely generic old school D&D quality to the quest and dialogues with npc characters throughout the game, very rote mid-century fantasy trash with no sense of identity of an ilk I find very personally unappealing. The other is the extremely charismatic and playful writing and design philosophy of the game’s writer, Roberta Williams. A lot of the scenarios in the game are just straight up cribbed from popular fables and fairy tales, but Williams engineers cute solutions, characterizing the player character Graham (who could have easily been a blank slate) as a guy who is both better suited to and prefers to use his wits to solve problems without violence whenever possible. Something that’s cool is that sometimes this is mandatory and sometimes it’s not. Yes, you do have to be diplomatic with the leprechaun community to get one of the items you need to finish the game, but you could absolutely kill that dragon and the giant at the top of the beanstalk if you really wanted to. Wouldn’t you rather just extinguish the dragon’s flame though? It’s not only more creative, it’s not only better role-playing, it’s a more fun solution to poke at and implement. And with the game’s cheeky humor and bevy of fast-coming game overs, you’re gonna be saving constantly anyway, so why not try stuff?

It’s a game that’s designed from all angles to really reward experimentation and creative play. The open world, the multiple solutions to problems, the free movement, the text parser; not all of these things were revolutionary for their time but together they were something really special. And despite these games’ reputation for needlessly obtuse and difficult puzzles (which they may well live up to somewhere down the line) there’s really only one genuine clunker here (all my homies hate Rumpelstiltskin). It makes sense that like, four franchises and an entire genre spawned from this. Even today I felt palpably excited playing it. It’s electric.

It’s very much a transitional piece between old timey text games and the modern style of adventure games that it heralds, so there’s an obvious feeling of age to it beyond the 1984 IBM graphics, which are actually super impressive (it’s fun to think that the equivalent of a AAA game dumping all their time and money into the first hour of the game because that’s all most people will play is having flags AND alligators that animate). I do think, however, that the text parser you use for all of your interactions beyond basic movement (and, frustratingly, like two other actions one time each) works really well, and all in all I didn’t have any trouble adapting to the control scheme at all.

There’s really a tug of war to the experience of playing King’s Quest 1 that define the experience as one that must have been really mind blowing compared to its contemporaries and still makes it feel unique and worthwhile today: one side is the extremely generic old school D&D quality to the quest and dialogues with npc characters throughout the game, very rote mid-century fantasy trash with no sense of identity of an ilk I find very personally unappealing. The other is the extremely charismatic and playful writing and design philosophy of the game’s writer, Roberta Williams. A lot of the scenarios in the game are just straight up cribbed from popular fables and fairy tales, but Williams engineers cute solutions, characterizing the player character Graham (who could have easily been a blank slate) as a guy who is both better suited to and prefers to use his wits to solve problems without violence whenever possible. Something that’s cool is that sometimes this is mandatory and sometimes it’s not. Yes, you do have to be diplomatic with the leprechaun community to get one of the items you need to finish the game, but you could absolutely kill that dragon and the giant at the top of the beanstalk if you really wanted to. Wouldn’t you rather just extinguish the dragon’s flame though? It’s not only more creative, it’s not only better role-playing, it’s a more fun solution to poke at and implement. And with the game’s cheeky humor and bevy of fast-coming game overs, you’re gonna be saving constantly anyway, so why not try stuff?

It’s a game that’s designed from all angles to really reward experimentation and creative play. The open world, the multiple solutions to problems, the free movement, the text parser; not all of these things were revolutionary for their time but together they were something really special. And despite these games’ reputation for needlessly obtuse and difficult puzzles (which they may well live up to somewhere down the line) there’s really only one genuine clunker here (all my homies hate Rumpelstiltskin). It makes sense that like, four franchises and an entire genre spawned from this. Even today I felt palpably excited playing it. It’s electric.

I didn't feel too good when I dropped out of my Computer Science uni degree, but I did think to myself : "At least I'll no longer be tormented by this awful 'Natural Language Engineering' module". Lo and Behold, this stupid discipline continues to ruin my life!

All of entertainment/culture gets fucked over by the profit motive, but I can't imagine a movie studio refusing to release Rashomon in the west and then 30 years later release "Rashomon 48fps Stereoscopic 4D Nanite CGI edition tech demo". There is a bare minimum pretense of respect for the medium.

Fuck You Square Enix! Just release the original, and while you're at it let me buy the Paranormasight OST.

All of entertainment/culture gets fucked over by the profit motive, but I can't imagine a movie studio refusing to release Rashomon in the west and then 30 years later release "Rashomon 48fps Stereoscopic 4D Nanite CGI edition tech demo". There is a bare minimum pretense of respect for the medium.

Fuck You Square Enix! Just release the original, and while you're at it let me buy the Paranormasight OST.

Alien Vendetta

2001

My previous classic Doom review here.

Meditations on Doom

=== Mechanics ===

Bangai-O Spirits, Treasure's 2008 DS masterpiece, is superficially quite like Doom in structure. All the levels can be created and changed with the included editor, and players can (jankily) share levels online. However, a distinct trait of the game is that Treasure's mastery of mechanics-as-such is remarkably tolerant of sloppy level design. Many of the included levels are borderline shitposts, and fittingly, one of the best is just a pixel-art portrait of the player character with lots of enemies thrown in. Treasure has done most of the work for you: all you need to do is place some stuff in the editor and let it rip.

In contrast, Doom levels need to be constructed with intentionality - certainly the enemies' AI pull some weight on their own but smart placement vastly amplifies their effectiveness. Huy Pham, creator of Deus Vult II, cites Alien Vendetta as a major inspiration and draws explicit comparisons to chess in the included text file:

"Map20 of DVII is a strong example of the Chess influence with the natural, non-teleport monster traps that simply springs from the map's sneaky layout. The Berserk trap on the uppermost level of Map20 is a reflection of a forced combination, with low health, the player is compelled to pick up the stimpack, entering the trap full of imps, grabbing the berserk as a counterattack, and then confronting the counter-counterattacking hell knight. In the yellow key complex, the two barons of hell were placed like two rooks on open files, firing down the corridor and putting pressure on the player's position and inducing him to make a mistake. The final archvile after taking the blue armor was placed in a way that parallels the black fianchettoed bishop in the Sicilian Dragon Yugoslav Attack opening, firing down the most crucial control point in the room."

The concept here is territory control. Chess is an apt comparison, but what's really interesting is to notice the similarities to shmups, that other game genre so focused on real-time territory control. The heavy emphasis on projectiles in Doom's combat means many common shmup techniques/concepts, such as streaming, moving with projectiles, misdirecting, safe spots, dodging within vs. outside of patterns, holding ground closer to enemies to keep control of space behind you, etc. directly translate.

In a structural sense, a tough section in a shmup demands a unity of macro-level routing, micro-level decisionmaking, and instinctual execution. Take Dodonpachi Daioujou's "hive" from stage 5. Clearing this demands the player work out a viable path that kills key enemies quickly while leaving movement paths open, have the requisite ability to precisely control their ship, and be able to quickly adapt to the slight unpredictability of bullet trajectories. Alien Vendetta's Map 32: No Guts No Glory (while being far less intense) uses those same core elements of macro-level routing through the map, micro-level decisionmaking via unpredictability of monster AI, and instinctual execution.

Like most shmups, and many older arcade-style games in general, there's also an intense focus on the fundamentals of movement and positioning. In this dev diary, Matthewmatosis talks about how compared to classic 2D games like Ghosts 'n Goblins, defensive decisionmaking in many 3D action games has been simplified by powerful get-out-of-jail-free cards such as rolls and parries:

"Imagine you were tasked with creating an AI which could complete these games without taking damage. You have access to all the relevant variables like enemy position and status, in other words you know when an attack is one frame away from hitting the player character. Despite being one of the most recent releases on the list, Devil May Cry 5 is one of the easiest to solve, especially if we’re talking about Bloody Palace. Simply attack until you’re in danger, then instantly activate Royalguard to negate damage. Others like Revengeance and Sekiro will require slightly more awareness about which attack type is coming but will ultimately be solved by pressing a certain button in response to the enemy...this isn’t some irrelevant curiosity, these defensive algorithms are running in your brain as you play...think about how clever Arthur’s [GnG player character] AI would need to be by comparison. If a grim reaper is running at him, it’s not enough to jump or throw a dagger on the last possible frame. You need to be able to think ahead and position yourself in the safest way to advance."

Doom is decidedly part of this old-school tradition, where avoiding sticky situations is contingent on many higher-level decisions that can't be easily reversed on a whim. High-level player David Assad has a great video on how survival in many tough fights demands creating space, which demands tactical play. Youtuber SoBad explains how the conventional advice about monster prioritization is in practice highly dependent on enemy positioning and composition (and he doesn't even mention infighting!). And in a nonlinear map, routing can recontextualize all of this.

My favorite map in Alien Vendetta is probably Anders Johnsen's Dark Dome. What's really cool about this map is how nearly the entire level is open to you from the start. This is because the entire level is shooting at you from the start. The opening minutes are a frenzied scramble to carve out a foothold somewhere as you dart around while constantly under fire. Clearing out one area opens up angles to attack new ones, which do the same in turn; this style of mapping has been called "zone-of-influence". And one of the great things that flows from this structure is how many viable ways there are to route the map. I used an invincibility to clear out a Archvile-guarded Revenant bonepile, but you might opt to assault from the window overlook instead and save it for one of the close-range Cyberdemon tangoes.

The "hot starts" in maps like Dark Dome also illuminates a truth: running away is deep! Trying to squeeze past a mob of chittering Revenants can be just as engaging as filling them with buckshot, and meaningfully deciding between the two is a joy rarely afforded in modern games. And those living Revenants won't just disappear: maybe later they'll pop back up at an inopportune time, or join the fray of another brawl. Mancubus battalions meet Cacodemon migrations; Cyberdemons rage at far-flung Revenant missiles; caged Archviles catch quick glimpses of their foe across twisted geometry; the boundaries between encounters, so rigid in most games, loosen, and their contents ooze together.

Certainly the door problem is a foremost cause of this rigidity, and some lock-ins here and there (like the BFG survival-horror blue key room) are far from unwelcome, but we can give up a bit of ground. Let the player play lame if they really want, you're not their babysitter. It's worth it when what's gained is a unique structure and flow that I haven't seen in any other game.