Chwoka

Completely off on my own here but this game right here made middle-school me hate and fear RPGs and I still haven't shaken it off, honestly. I hit some kind of point where I believed I needed to grind to progress and it hit me like a punch in the stomach. Then I realized that I dreaded the prospect so much because I fundamentally and deeply hated the whole tedious menu-battling character-optimizing system that every battle was — that is, what I was dreading was having to suffer ANY MORE of the actual gameplay part of the game. Up to that point, I hadn't even thought if I was enjoying myself or not, just killing time. It's not like I was particularly invested in the story. It occurred to me that a quicker way to not have to do any more battles was just to stop playing, so I did, and wrote off the entire RPG genre.

From my blog, Arcade Idea

When Philo T. Farnsworth first demonstrated his all-electronic CRT television to anyone outside of the laboratory where it was invented, he said "here's something the bankers can understand" and turned it on to produce an image of a dollar bill. When Thomas T. Goldsmith was trying to come up with a way for the user to directly interface with the CRT for trifling amusement rather than a practical use-case, he made a game where you shoot down planes. These are eerie portents of the future — no, scratch that, full-on curses invoked that the respective mediums have not yet recovered from.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FBgvS2OuFwI

Stan Kenton Orchestra (composer Bob Graettinger) - Thermopylae [1947]

Television and video games are, to my mind, siblings. They're cursed and compromised mediums, and art within it has to come to terms with the attendant formal inertia. They were born in the same wave of technological innovation. A console is functionally an extra TV channel. Artworks in both mediums often pointedly aspire to cinema, a tendency long-present but especially pronounced in the 21st century. This is in obvious compensation to the stench of disposable disrepute that dogs them. Both mediums are restlessly oriented towards the future, perhaps owing to their history of technological advance, and thus have a largely tenuous, fraught relationship with its own past, where nostalgia has had to balance against shame over how primitive, corny earlier works. So even as it tries to excite the audience about the next thing, it's constantly repeating itself in ways both small and large. Both have murky, obscure, protracted technical origins in laboratories decades before being ready for consumers, and then they ascend to being a dominant — arguably the dominant — mass medium of their time.

World War 2 put a serious damper on the entrance of television into mass popularity, but at the same time, the US government pumped a lot of money into the research and development of television technology for military purposes. The whole American television industry, which had never yet lived up to its own decades of hype and been able to profit by manufacturing and selling a real product to consumers in any substantial quantity, pivoted instead to the lucrative prospect of war grants. We all know about radar, but there were also dreams of infrared night-vision & sniper lasers, and of TV-guided precision missiles. This latter endeavor directly led to the creation of the image orthicon, which would become the very linchpin that made commercial television practical from 1945 to 1968, the "Immy" for which the Emmys are still named.

So when Goldsmith in the DuMont laboratory 2 years out from the war was trying to think of a fictional context for his Cathode Ray Tube Amusement Device [1947], it cannot really be considered surprising that his mind leapt to a combination between radar and the TV-guided missile. In CRT Amusement Device, the player adjusts a lobbing arc drawn across a radar-style circular screen from the bottom-left up and to the right, and they also get to brighten the beam at any point of their choosing within that arc. All interface is via dials. A transparent overlay is physically placed on the screen: images of planes that are targets for the player to hit. To make this task a challenge, there's a timer, entirely separate from the rest of the equipment. Despite being so simple, this immediately raises a number of questions. Firstly, is this a video game?

That's a tricky question, because here in 2022, we're still not totally sure what video games are. The progenitors of television knew their goal exactly and set out to make it happen. It's a bit strong to say that video games were conversely invented by accident, but it was a slow process of conceptual evolution that never really stopped. Roughly speaking, the world saw Pong [1972], came up with a phrase for "things like Pong", and then that phrase gradually stretched to include everything on this blog and much more. That's exactly what's interesting about these early, pre-commercial years: people are working out what video games are and what they're for for the first time with no preconceptions, and little-to-no knowledge of any predecessors in the field whatsoever. CRT Amusement Device, in my book, is definitely conceptually in-line with Pong: not only does it look and play a bit like Tennis For Two [1958] (also from DuMont's lab,) it manages with its "overlay" technology to bear an even stronger resemblance to the Magnavox Odyssey [1971] that inspired Pong, enough to eventually surface as a trump card against the legal claim on originating and rent-gathering on the Television Game concept.

There's a documentary on YouTube called "The First Video Game" that I sincerely recommend as an inventory and exploration of extremely early video games. However, I must respectfully disagree with its prescriptive approach, in particular its final criteria:

"A video game must:

1) Exist in a practical implementation

2) Generate some kind of video signal

3) Have interaction that alters this signal

4) Be principally intended for entertainment

5) Be playable solely through the video display(s)"

quibble with points 1, 2, 4, and 5, which means I reach different conclusions.

-- To point 2: Games like The Oregon Trail [1971] were originally developed for teletype machines with a printed display, did not change their very nature by transferring to monitor display, and there have been experimental audio-only games as well. The presence of the word video in "video game" is historical accident, not a determinant. "Computer games" or "digital games" would probably be more accurate, although one objection to CRT Amusement Device not covered in this list is that it's not running on a digital computer but an electronic series of wave generators and variable resistors, without even so much as a transistor, semiconductor, or memory. This is a fair point, but I don't think the underlying technicalities of construction makes a lot of difference to the end experience.

-- To point 5: Many games rely on external knowledge or input beyond the bounds of its visual display. Any game that requires mapping, or for you to read the manual, or, as in the case of the Magnavox Odyssey and CRT Amusement Device, for the player to impose external constraints on their own technologically-unlimited behavior. I think this item is principally intended to exclude electro-mechanical games like pinball machines and shooting galleries, which is fair because they rely on real-world unsimulated physics, even though the story of those games, their creators, and their social position so seamlessy leads into the story of arcade video games in the 1970s.

-- To point 4: There are video games not principally intended for entertainment.

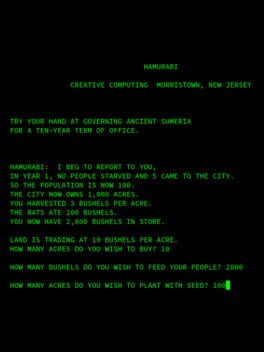

-- Most interestingly, to point 1: What counts as a "practical implementation" in a medium that is largely digital? Sources are unclear if any CRT Amusement Device prototype ever physically existed or not, but either way that object doesn't exist now. What we're left with is the patent documentation, which are instructions sufficient to build our own replica if inclined. As covered in the post on Hamurabi [1968/1973], the "type-in" game was a common distribution method throughout the 70s where you would print the source code to the game on paper for the end-user to manually re-inscribe on their own machines like a monk. Indeed, any video game that isn't a hardwired unit really is fundamentally distributed as instructions for building itself.

This is the whole problem with defining things that are out there in the world, they're so easy to problematize with annoying exceptions and objections drawn from the ranks of things we would common-sensically include in the category. I could and maybe might quibble with point 3 some more, like when I get to the "kinetic novel," which are perhaps culturally video games despite being non-interactive. For now though, let's accept that a video game must respond to input from the player.

When I wrote about the Magnavox Odyssey two whole years ago, I compared it to shining a flashlight on a board game. A recent article by Doc Burford, on the art of how to be making your players give a fuck [2022], reminded me of this. Early on, it makes a point that a flashlight is interactive electronics: You press a button and the light turns on or off. So point 3 alone is clearly insufficient for thinking about video games. Marshall McLuhan made a similar point about lightbulbs in general in Understanding Media [1964], that they were a medium without content and with an effect. But you can assemble the lightbulbs into letters or make them flash in morse code, and now you have a whole semantic grammar as well as those original effects, and that's how McLuhan approaches into television. They sharply diverge from there. McLuhan tells us about that the medium is the message, above whatever its semantic content happens to be. Bruford tells us that without content, we don't really have a medium at all. A television with no content isn't television, it's a white noise generating appliance. (Arguably, much or all of the content on television does not move beyond this status.) Likewise, an interaction with a computer or other electronic device does not become a potential art medium until the player gives a fuck in their minds about the lights being on or off, usually by how that interweaves with other lights and your choice of on or off in a legible pattern. He specifically exempts Tetris [1984] from this, but surely for all its abstraction, Tetris is a language and you give a fuck how it's arranged.

CRT Amusement Device is barely more than a flashlight itself, or more accurately, an oscilloscope. Drawing an arc on the screen isn't a game. Drawing an arc on the screen that gets brighter at a particular point in the arc isn't a game. It's maybe a toy, or a tool if you can find a good use for an arc on the screen. It's the imagination that makes it a game. Games didn't have much in the way of storytelling before 1980, but they almost always had a premise. The timer just gives it friction. The earliest computer game I know of is actually Nimatron [1940], a Nim-playing computer. But I'm not interested in video games that just replicate older forms of games here, I'm specifically interested in games like this, games that explore original concepts for computer space. And this is the earliest attempt at that that I know of.

In the patent documentation itself, the player is simply hitting targets, and airplanes are just a sole example of what those targets might be. This is in contrast to the Magnavox Odyssey's passionate desperation to make its lights represent as many different things as they could think of, in many different play-styles. While the gameplay of CRT Amusement Device could be easily reskinned to not be airplanes, it wasn't, and it's not flexible like that. It's always target practice. It's always a World War 2 fantasy of radar and the guided missile, even if you pretended it was the spray from a hose, or needles into Bloons [2007].

Shooting targets has always had an insistent central prominence in video games, regardless of actual popularity and commercial success. It's got a gravitational pull. When the video games industry was called up before the United States congress for its own "vast wasteland" moment, it wasn't for low quality, it was for the worry that they were training the youth to be violent like at war but at home. Video games were born of war. Trajectories, competition, elimination, drilling over and over again to improve performance and self-discipline. That's not every video game, but it's never far away.

When Philo T. Farnsworth first demonstrated his all-electronic CRT television to anyone outside of the laboratory where it was invented, he said "here's something the bankers can understand" and turned it on to produce an image of a dollar bill. When Thomas T. Goldsmith was trying to come up with a way for the user to directly interface with the CRT for trifling amusement rather than a practical use-case, he made a game where you shoot down planes. These are eerie portents of the future — no, scratch that, full-on curses invoked that the respective mediums have not yet recovered from.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FBgvS2OuFwI

Stan Kenton Orchestra (composer Bob Graettinger) - Thermopylae [1947]

Television and video games are, to my mind, siblings. They're cursed and compromised mediums, and art within it has to come to terms with the attendant formal inertia. They were born in the same wave of technological innovation. A console is functionally an extra TV channel. Artworks in both mediums often pointedly aspire to cinema, a tendency long-present but especially pronounced in the 21st century. This is in obvious compensation to the stench of disposable disrepute that dogs them. Both mediums are restlessly oriented towards the future, perhaps owing to their history of technological advance, and thus have a largely tenuous, fraught relationship with its own past, where nostalgia has had to balance against shame over how primitive, corny earlier works. So even as it tries to excite the audience about the next thing, it's constantly repeating itself in ways both small and large. Both have murky, obscure, protracted technical origins in laboratories decades before being ready for consumers, and then they ascend to being a dominant — arguably the dominant — mass medium of their time.

World War 2 put a serious damper on the entrance of television into mass popularity, but at the same time, the US government pumped a lot of money into the research and development of television technology for military purposes. The whole American television industry, which had never yet lived up to its own decades of hype and been able to profit by manufacturing and selling a real product to consumers in any substantial quantity, pivoted instead to the lucrative prospect of war grants. We all know about radar, but there were also dreams of infrared night-vision & sniper lasers, and of TV-guided precision missiles. This latter endeavor directly led to the creation of the image orthicon, which would become the very linchpin that made commercial television practical from 1945 to 1968, the "Immy" for which the Emmys are still named.

So when Goldsmith in the DuMont laboratory 2 years out from the war was trying to think of a fictional context for his Cathode Ray Tube Amusement Device [1947], it cannot really be considered surprising that his mind leapt to a combination between radar and the TV-guided missile. In CRT Amusement Device, the player adjusts a lobbing arc drawn across a radar-style circular screen from the bottom-left up and to the right, and they also get to brighten the beam at any point of their choosing within that arc. All interface is via dials. A transparent overlay is physically placed on the screen: images of planes that are targets for the player to hit. To make this task a challenge, there's a timer, entirely separate from the rest of the equipment. Despite being so simple, this immediately raises a number of questions. Firstly, is this a video game?

That's a tricky question, because here in 2022, we're still not totally sure what video games are. The progenitors of television knew their goal exactly and set out to make it happen. It's a bit strong to say that video games were conversely invented by accident, but it was a slow process of conceptual evolution that never really stopped. Roughly speaking, the world saw Pong [1972], came up with a phrase for "things like Pong", and then that phrase gradually stretched to include everything on this blog and much more. That's exactly what's interesting about these early, pre-commercial years: people are working out what video games are and what they're for for the first time with no preconceptions, and little-to-no knowledge of any predecessors in the field whatsoever. CRT Amusement Device, in my book, is definitely conceptually in-line with Pong: not only does it look and play a bit like Tennis For Two [1958] (also from DuMont's lab,) it manages with its "overlay" technology to bear an even stronger resemblance to the Magnavox Odyssey [1971] that inspired Pong, enough to eventually surface as a trump card against the legal claim on originating and rent-gathering on the Television Game concept.

There's a documentary on YouTube called "The First Video Game" that I sincerely recommend as an inventory and exploration of extremely early video games. However, I must respectfully disagree with its prescriptive approach, in particular its final criteria:

"A video game must:

1) Exist in a practical implementation

2) Generate some kind of video signal

3) Have interaction that alters this signal

4) Be principally intended for entertainment

5) Be playable solely through the video display(s)"

quibble with points 1, 2, 4, and 5, which means I reach different conclusions.

-- To point 2: Games like The Oregon Trail [1971] were originally developed for teletype machines with a printed display, did not change their very nature by transferring to monitor display, and there have been experimental audio-only games as well. The presence of the word video in "video game" is historical accident, not a determinant. "Computer games" or "digital games" would probably be more accurate, although one objection to CRT Amusement Device not covered in this list is that it's not running on a digital computer but an electronic series of wave generators and variable resistors, without even so much as a transistor, semiconductor, or memory. This is a fair point, but I don't think the underlying technicalities of construction makes a lot of difference to the end experience.

-- To point 5: Many games rely on external knowledge or input beyond the bounds of its visual display. Any game that requires mapping, or for you to read the manual, or, as in the case of the Magnavox Odyssey and CRT Amusement Device, for the player to impose external constraints on their own technologically-unlimited behavior. I think this item is principally intended to exclude electro-mechanical games like pinball machines and shooting galleries, which is fair because they rely on real-world unsimulated physics, even though the story of those games, their creators, and their social position so seamlessy leads into the story of arcade video games in the 1970s.

-- To point 4: There are video games not principally intended for entertainment.

-- Most interestingly, to point 1: What counts as a "practical implementation" in a medium that is largely digital? Sources are unclear if any CRT Amusement Device prototype ever physically existed or not, but either way that object doesn't exist now. What we're left with is the patent documentation, which are instructions sufficient to build our own replica if inclined. As covered in the post on Hamurabi [1968/1973], the "type-in" game was a common distribution method throughout the 70s where you would print the source code to the game on paper for the end-user to manually re-inscribe on their own machines like a monk. Indeed, any video game that isn't a hardwired unit really is fundamentally distributed as instructions for building itself.

This is the whole problem with defining things that are out there in the world, they're so easy to problematize with annoying exceptions and objections drawn from the ranks of things we would common-sensically include in the category. I could and maybe might quibble with point 3 some more, like when I get to the "kinetic novel," which are perhaps culturally video games despite being non-interactive. For now though, let's accept that a video game must respond to input from the player.

When I wrote about the Magnavox Odyssey two whole years ago, I compared it to shining a flashlight on a board game. A recent article by Doc Burford, on the art of how to be making your players give a fuck [2022], reminded me of this. Early on, it makes a point that a flashlight is interactive electronics: You press a button and the light turns on or off. So point 3 alone is clearly insufficient for thinking about video games. Marshall McLuhan made a similar point about lightbulbs in general in Understanding Media [1964], that they were a medium without content and with an effect. But you can assemble the lightbulbs into letters or make them flash in morse code, and now you have a whole semantic grammar as well as those original effects, and that's how McLuhan approaches into television. They sharply diverge from there. McLuhan tells us about that the medium is the message, above whatever its semantic content happens to be. Bruford tells us that without content, we don't really have a medium at all. A television with no content isn't television, it's a white noise generating appliance. (Arguably, much or all of the content on television does not move beyond this status.) Likewise, an interaction with a computer or other electronic device does not become a potential art medium until the player gives a fuck in their minds about the lights being on or off, usually by how that interweaves with other lights and your choice of on or off in a legible pattern. He specifically exempts Tetris [1984] from this, but surely for all its abstraction, Tetris is a language and you give a fuck how it's arranged.

CRT Amusement Device is barely more than a flashlight itself, or more accurately, an oscilloscope. Drawing an arc on the screen isn't a game. Drawing an arc on the screen that gets brighter at a particular point in the arc isn't a game. It's maybe a toy, or a tool if you can find a good use for an arc on the screen. It's the imagination that makes it a game. Games didn't have much in the way of storytelling before 1980, but they almost always had a premise. The timer just gives it friction. The earliest computer game I know of is actually Nimatron [1940], a Nim-playing computer. But I'm not interested in video games that just replicate older forms of games here, I'm specifically interested in games like this, games that explore original concepts for computer space. And this is the earliest attempt at that that I know of.

In the patent documentation itself, the player is simply hitting targets, and airplanes are just a sole example of what those targets might be. This is in contrast to the Magnavox Odyssey's passionate desperation to make its lights represent as many different things as they could think of, in many different play-styles. While the gameplay of CRT Amusement Device could be easily reskinned to not be airplanes, it wasn't, and it's not flexible like that. It's always target practice. It's always a World War 2 fantasy of radar and the guided missile, even if you pretended it was the spray from a hose, or needles into Bloons [2007].

Shooting targets has always had an insistent central prominence in video games, regardless of actual popularity and commercial success. It's got a gravitational pull. When the video games industry was called up before the United States congress for its own "vast wasteland" moment, it wasn't for low quality, it was for the worry that they were training the youth to be violent like at war but at home. Video games were born of war. Trajectories, competition, elimination, drilling over and over again to improve performance and self-discipline. That's not every video game, but it's never far away.

1987

From my blog, Arcade Idea.

As wont as I am to call everything some kind of "adventure game", citing the enormous and cross-genre influence of Colossal Cave Adventure [1975/77], this is pointedly trying NOT to be an adventure game, for all its resemblance. You can tell, because it has an adventure game inside of itself, which exists to parody adventure games and thereby define how this game is something else on a parallel track. This parody is a maze to fumble around in, bumping into various generic fantasy creatures (elves, pixies, and whatnot) who all block your path further into the maze until you bring them the item that will satisfy their varied and peculiar demands. It's a anthropomorphication of the classic "lock-and-key" inventory-management puzzle solved through complete exploration of every nook and cranny of a convoluted space that we see all over the place. It's quite the stretch to call this business "puzzles" at all, despite customary lingo. The "puzzles," such as they are in your usual adventure game, are not actually that mechanism but the obscuring of that mechanism, the creation of ambiguity around which well-hidden key goes with which lock and how you are meant to turn it, but it's here delivered with barebones set dressing which may be charming and witty but which does nothing to obscure its simplistic functioning to the player, rendering itself as dumb brute force that only tests patience and persistence — which is something you very often see in the usual non-parodic adventure game, too. Other than in this parody, there is actually no inventory system in this game, despite it having the bog-standard adventure game premise of collecting 14 treasures.

---- MUSICAL INTERLUDE: LL Cool J - My Rhyme Ain't Done [1987] -----

Like Sokoban [1982] or Tetris [1984] or Chain Shot [1985] (aka SameGame), The Fool's Errand [1987] brings to my little ad-hoc canon of video games a whole new idea of what a "video game puzzle" even can be. Unlike those games, it doesn't just give us one great puzzle mechanic, it brings us dozens of bespoke minigames, such that it's structurally reminiscent of art games like The Prisoner [1980] or Lifespan [1983]. It gives to the history a whole philosophy and tradition from outside video games, mixed with its own novel concepts that could only be done in video games. It is a digital work inspired by those magazines full of brain teasers you see at supermarket checkout stands and their more sophisticated and upscale sibling, those analog gamebooks that give its puzzling some kind of overarching throughline and cohesion through things like a narrative scaffolding or a meta-puzzle or even a real-world treasure hunt. This idea will stick with video games (see: The 7th Guest [1993], Professor Layton and the Curious Village [2007]) but rarely, if ever, will it be done quite as well as it is here (see: The 7th Guest [1993].)

(This isn't a review, but that's showing my hand: this is flat-out one of the best games I've ever played, hasn't "aged" a day for as much as I resent that framing, and I heartily recommend you play it if you're reading this and it at all intrigues you. It's free from the original creator Cliff Johnson now and one of the easiest to get running that I've ever played for this blog. Also, there was no natural place to note it in the body of the text, so here in the praise aside: this has its visual aesthetics totally on lock and is one of the most strikingly gorgeous games ever made, certainly made by 1987. I know I say that about every Macintosh game I play but I really really mean it here. I believe, though I'm not sure, that the beautiful artwork may have been the handiwork of someone named Brad Parker.)

The remaining puzzles not coming from that storied paradigm, which I'll address first, are instead highly interface-reliant. The Macintosh the game was made for has a mouse, and in the 80s this is still a bold novelty to experiment with, reminiscent of the way Nintendo DS games could get very excited over ways to ask the player to use the touchscreen. The Fool's Errand will ask you to move your mouse in specific choreographed ways, or to scan your mouse over the screen, or to keep your mouse still. The puzzles in this category are actually either tests of physical performance or, like the good versions of the lock-and-key puzzles it parodies, actually a puzzle of figuring out through its ambiguity and obscurity what exactly you're meant to do and then is no puzzle at all after.

This philosophy also shores up the more traditional-seeming puzzles. Some of the rules to various puzzles are plainly stated to the player, but others are quite deliberately not. Instead, the player finds themself already digitally bound by these rules and sometimes must deduce what those restrictions even are through experimenting within the interface, in a way that could not be replicated in print. Sometimes the game doesn't even tell the player the ultimate goal to be working towards.

If "an adventure game is a crossword at war with a narrative," as Graham Nelson wrote in 1995, then in The Fool's Errand the crossword wins possibly too handily to qualify. Many, perhaps most, of this game's puzzles revolve around some form of wordplay. Not as in puns and rhymes and such, but things like anagrams and cyphers and word searches and literal crosswords which attune you not so much to the sense or sound of the words but call attention to the particulars of its actual constituent letters. Often, The Fool's Errand will provide you with mere nonsense that the narrative transparently and comically strains to manufacture a half-logical pretext for using in a sentence, or literal gibberish to which you are to subject the same rigors as the perfectly cromulent words that are mixed right in with it.

Which brings me to the game's regard towards text, a subject on which I'd be tempted to call it "agnostic" if it wasn't so darn gnostic. As indicated, it structurally doesn't care about the "meaning" of text, and I mean that in the extremely basic "See Spot Run" sense where to "interpret" or "comprehend" the text is to firstly process the concepts of things like "run" and "see", and then secondly to pay attention to how these concepts one by one connect and build on one another through grammar into something that makes sense, typically something with some nominal weight of real-life apprehension underpinning its semiotics somewhere. The Fool's Errand has long passages of witty prose that operate on the level of comprehensibility perfectly well. There's a narrative about a peace between the four kingdoms of the realm that, under pressure of famine and petty grievances and misunderstandings and magical schemes, is threatening to curdle right back into war unless The Fool can stop it through collecting treasures and counterspells. It just is rarely interested in the various kinds of textual interpretation afforded by that approach; it's there, I could readily perform a deeper exegesis of it, but it's not the one that is incentivized and prized.

This is one crucial thing separating the player and the Fool, who they are aligned with but certainly do not directly control nor embody: The Fool thinks his world is real and approaches it as such, taking the information he is given as if it is has some weight of fact behind it, and when it does not seem to have such a significance, that this is a failure or malfunction. Other characters say things to The Fool that only make sense to the player who has access to the actual game bits, and The Fool "gets weary of such confusing talk and [does] not wish to consider [it] at all," or conversely he'll seriously entertain the aforementioned strained justifications for using silly words. He misapprehends a giant symbolic totem which then has to explicitly tell him that it is a symbol and what it is a symbol for twice over before he recognizes the pattern. This may be the very thing that makes him a fool: He has no access to nor awareness of the true nature of his universe — maybe you can see now what I meant by "gnostic" — which is apparent to the reader as fictional, linguistically-constructed, gamified, and dense with symbolism.

The kind of reading The Fool's Errand is more invested in is a pseudo-esotericist one. The whole game is tarot-themed, with all of its characters and events and many of its items drawn from the tarot traditions. This cues the reader to not read its prose so literally. A layperson with only the vaguest knowledge of tarot still knows that when they see objects in a tarot context that that object is not to be understood as just plain-and-simple being that object. A sword isn't a sword, it's a metaphor for... something (the layperson won't know what,) and even part of its own system of metaphors parseable only by those who have trained to parse it. But The Fool's Errand, as best as I can tell, doesn't much leverage the traditional divinatory significance and readings of, say, The Empress, or the actual contents of any of The Book Of Thoth it invokes repeatedly. The Fool's Errand's usage of the things on tarot cards seems to be uniquely its own takes, self-contained, self-explaining as much as they need to be, and only lightly and occasionally informed by pre-existing tarot usage, such as The Fool himself being the wandering protagonist. And thank goodness, for my sake. I don't know much about tarot, and did just enough research hitting the books to realize it wouldn't be terribly relevant for properly reading nor playing this particular game. (Though then again, I can hardly be terribly confident in that conclusion. If you're more steeped in tarot than I, please play the game and tell me that I'm wrong in the comments section below!) Thank goodness for its sake, too. The game casts The High Priestess as an outright cackling villain to be defeated triumphantly, which would be quite thematically alarming and even bizarrely misogynist if she were meant to represent the mysterious half of femininity, but she's not used that way.

Its engagement with the symbols of tarot is ultimately similar to its engagement with the symbols that constitute the alphabet. While esotericist reading strategies are often posited as a way to get beyond surfaces and see a deeper reality than even the one we think we are familiar with, The Fool's Errand instead playfully focuses its attention right in on the surface, steadily devaluing the idea of even an knowingly-illusory reality effect. The narration is mostly a veiled pretense that, like the game's many anagrams, needs to be unjumbled and deciphered for information that can then be instrumentalized for the purpose of organizing a big sliding image tile puzzle and sorting syllables. It encourages the player to plunder its prose for encrypted data in search of not secret knowledge but secret treasure. The game and eventually the player is far more concerned with the deft interplay of these symbols qua symbols connecting and collecting within its own systems than the things the symbols usually gesture at.

Folks, we might have ourselves a hypertext here. It's borderline, but it's striking to me. Structurally, while there's no direct hyperlinks from one page to the next, the game's story is conceptualized as pages to be approached in arbitrary order. There is a final and proper canonical order, but filling in its gaps is itself a major overarching challenge. The classic logic of this-then-that narrative order and causality is invoked but obscured and its discovery is gamified. Pages are locked off by puzzle completion, and the pages you start with unlocked aren't all the first pages. Instead, the minigames pitch you hither and tither across the text, most often to the next page but just as likely clear into a different chapter. The narrative's been fragmented into episodic vignettes, and they often seemed to me to make just as much sense in that secondary order as in the primary order, like when I had a hard time with a puzzle and the next page unlocked began with The Fool also feeling exhausted from effort. You can read the last page right from the start, and the best straightforward explanation of what's going on and what you are to do is found in the similarly-available second-to-last chapter. Spiritually, there's also a distinct bent to the game where it's majorly concerned with connections and greedily gathering data points up, and delighted by the sheer architecture of its own semiotic house of mirrors, with only light concern if any for what it all adds up to or points at that ultimately makes it feel to me more "postmodern" (and hypertextual) than esotericist.

It's interesting just how much of a boom there is for node-based narrative here in the late 1980s. Partially that's an artifact of my selections, but I know for sure they're actually surprisingly sparse in the early 1980s. We've sadly seen the last Infocom game we're going to see on this blog already, but as the little-disputed critical and commercial leading light of text adventures recedes, we see not only the market but the texts themselves fragmenting — if you're even going to be considering this sort of thing as occupying the same aesthetic and niche that that sort of thing does as well at other times, which has become a fundamental guiding principle of the concept of "interactive fiction" but only as it was formulated through controversy. The parser norms of interactive fiction will reassert themselves in an Infocom-derived renaissance in the mid-90s, but then around the turn of the 2010s it zags back to hypertext again, possibly for good. Alternatively, if you see hypertext as something wholly separate from and even defined against the parser adventure game tradition, as The Fool's Errand suggests it to be, this was a savvy move from the parser camp to rhetorically capture and encompass a now-more-popular genre entirely within its own tradition. Either way, that makes this little interregnum feel like foreshadowing, all the moreso because a lot of these games are being made by people who come from backgrounds outside of gaming working solo or close to it who thereby have more offbeat perspectives and tones than the programmers we've been used to.

-------------

Thanks to Monkeysky for getting inspired to play the game at the same time as me so we could talk about it. Thanks to hypodronic for the recommendation of Lon Milo DuQuette's "Understanding Aleister Crowley's Thoth Tarot" — didn't bear much fruit for this article but did give me some sea legs.

As wont as I am to call everything some kind of "adventure game", citing the enormous and cross-genre influence of Colossal Cave Adventure [1975/77], this is pointedly trying NOT to be an adventure game, for all its resemblance. You can tell, because it has an adventure game inside of itself, which exists to parody adventure games and thereby define how this game is something else on a parallel track. This parody is a maze to fumble around in, bumping into various generic fantasy creatures (elves, pixies, and whatnot) who all block your path further into the maze until you bring them the item that will satisfy their varied and peculiar demands. It's a anthropomorphication of the classic "lock-and-key" inventory-management puzzle solved through complete exploration of every nook and cranny of a convoluted space that we see all over the place. It's quite the stretch to call this business "puzzles" at all, despite customary lingo. The "puzzles," such as they are in your usual adventure game, are not actually that mechanism but the obscuring of that mechanism, the creation of ambiguity around which well-hidden key goes with which lock and how you are meant to turn it, but it's here delivered with barebones set dressing which may be charming and witty but which does nothing to obscure its simplistic functioning to the player, rendering itself as dumb brute force that only tests patience and persistence — which is something you very often see in the usual non-parodic adventure game, too. Other than in this parody, there is actually no inventory system in this game, despite it having the bog-standard adventure game premise of collecting 14 treasures.

---- MUSICAL INTERLUDE: LL Cool J - My Rhyme Ain't Done [1987] -----

Like Sokoban [1982] or Tetris [1984] or Chain Shot [1985] (aka SameGame), The Fool's Errand [1987] brings to my little ad-hoc canon of video games a whole new idea of what a "video game puzzle" even can be. Unlike those games, it doesn't just give us one great puzzle mechanic, it brings us dozens of bespoke minigames, such that it's structurally reminiscent of art games like The Prisoner [1980] or Lifespan [1983]. It gives to the history a whole philosophy and tradition from outside video games, mixed with its own novel concepts that could only be done in video games. It is a digital work inspired by those magazines full of brain teasers you see at supermarket checkout stands and their more sophisticated and upscale sibling, those analog gamebooks that give its puzzling some kind of overarching throughline and cohesion through things like a narrative scaffolding or a meta-puzzle or even a real-world treasure hunt. This idea will stick with video games (see: The 7th Guest [1993], Professor Layton and the Curious Village [2007]) but rarely, if ever, will it be done quite as well as it is here (see: The 7th Guest [1993].)

(This isn't a review, but that's showing my hand: this is flat-out one of the best games I've ever played, hasn't "aged" a day for as much as I resent that framing, and I heartily recommend you play it if you're reading this and it at all intrigues you. It's free from the original creator Cliff Johnson now and one of the easiest to get running that I've ever played for this blog. Also, there was no natural place to note it in the body of the text, so here in the praise aside: this has its visual aesthetics totally on lock and is one of the most strikingly gorgeous games ever made, certainly made by 1987. I know I say that about every Macintosh game I play but I really really mean it here. I believe, though I'm not sure, that the beautiful artwork may have been the handiwork of someone named Brad Parker.)

The remaining puzzles not coming from that storied paradigm, which I'll address first, are instead highly interface-reliant. The Macintosh the game was made for has a mouse, and in the 80s this is still a bold novelty to experiment with, reminiscent of the way Nintendo DS games could get very excited over ways to ask the player to use the touchscreen. The Fool's Errand will ask you to move your mouse in specific choreographed ways, or to scan your mouse over the screen, or to keep your mouse still. The puzzles in this category are actually either tests of physical performance or, like the good versions of the lock-and-key puzzles it parodies, actually a puzzle of figuring out through its ambiguity and obscurity what exactly you're meant to do and then is no puzzle at all after.

This philosophy also shores up the more traditional-seeming puzzles. Some of the rules to various puzzles are plainly stated to the player, but others are quite deliberately not. Instead, the player finds themself already digitally bound by these rules and sometimes must deduce what those restrictions even are through experimenting within the interface, in a way that could not be replicated in print. Sometimes the game doesn't even tell the player the ultimate goal to be working towards.

If "an adventure game is a crossword at war with a narrative," as Graham Nelson wrote in 1995, then in The Fool's Errand the crossword wins possibly too handily to qualify. Many, perhaps most, of this game's puzzles revolve around some form of wordplay. Not as in puns and rhymes and such, but things like anagrams and cyphers and word searches and literal crosswords which attune you not so much to the sense or sound of the words but call attention to the particulars of its actual constituent letters. Often, The Fool's Errand will provide you with mere nonsense that the narrative transparently and comically strains to manufacture a half-logical pretext for using in a sentence, or literal gibberish to which you are to subject the same rigors as the perfectly cromulent words that are mixed right in with it.

Which brings me to the game's regard towards text, a subject on which I'd be tempted to call it "agnostic" if it wasn't so darn gnostic. As indicated, it structurally doesn't care about the "meaning" of text, and I mean that in the extremely basic "See Spot Run" sense where to "interpret" or "comprehend" the text is to firstly process the concepts of things like "run" and "see", and then secondly to pay attention to how these concepts one by one connect and build on one another through grammar into something that makes sense, typically something with some nominal weight of real-life apprehension underpinning its semiotics somewhere. The Fool's Errand has long passages of witty prose that operate on the level of comprehensibility perfectly well. There's a narrative about a peace between the four kingdoms of the realm that, under pressure of famine and petty grievances and misunderstandings and magical schemes, is threatening to curdle right back into war unless The Fool can stop it through collecting treasures and counterspells. It just is rarely interested in the various kinds of textual interpretation afforded by that approach; it's there, I could readily perform a deeper exegesis of it, but it's not the one that is incentivized and prized.

This is one crucial thing separating the player and the Fool, who they are aligned with but certainly do not directly control nor embody: The Fool thinks his world is real and approaches it as such, taking the information he is given as if it is has some weight of fact behind it, and when it does not seem to have such a significance, that this is a failure or malfunction. Other characters say things to The Fool that only make sense to the player who has access to the actual game bits, and The Fool "gets weary of such confusing talk and [does] not wish to consider [it] at all," or conversely he'll seriously entertain the aforementioned strained justifications for using silly words. He misapprehends a giant symbolic totem which then has to explicitly tell him that it is a symbol and what it is a symbol for twice over before he recognizes the pattern. This may be the very thing that makes him a fool: He has no access to nor awareness of the true nature of his universe — maybe you can see now what I meant by "gnostic" — which is apparent to the reader as fictional, linguistically-constructed, gamified, and dense with symbolism.

The kind of reading The Fool's Errand is more invested in is a pseudo-esotericist one. The whole game is tarot-themed, with all of its characters and events and many of its items drawn from the tarot traditions. This cues the reader to not read its prose so literally. A layperson with only the vaguest knowledge of tarot still knows that when they see objects in a tarot context that that object is not to be understood as just plain-and-simple being that object. A sword isn't a sword, it's a metaphor for... something (the layperson won't know what,) and even part of its own system of metaphors parseable only by those who have trained to parse it. But The Fool's Errand, as best as I can tell, doesn't much leverage the traditional divinatory significance and readings of, say, The Empress, or the actual contents of any of The Book Of Thoth it invokes repeatedly. The Fool's Errand's usage of the things on tarot cards seems to be uniquely its own takes, self-contained, self-explaining as much as they need to be, and only lightly and occasionally informed by pre-existing tarot usage, such as The Fool himself being the wandering protagonist. And thank goodness, for my sake. I don't know much about tarot, and did just enough research hitting the books to realize it wouldn't be terribly relevant for properly reading nor playing this particular game. (Though then again, I can hardly be terribly confident in that conclusion. If you're more steeped in tarot than I, please play the game and tell me that I'm wrong in the comments section below!) Thank goodness for its sake, too. The game casts The High Priestess as an outright cackling villain to be defeated triumphantly, which would be quite thematically alarming and even bizarrely misogynist if she were meant to represent the mysterious half of femininity, but she's not used that way.

Its engagement with the symbols of tarot is ultimately similar to its engagement with the symbols that constitute the alphabet. While esotericist reading strategies are often posited as a way to get beyond surfaces and see a deeper reality than even the one we think we are familiar with, The Fool's Errand instead playfully focuses its attention right in on the surface, steadily devaluing the idea of even an knowingly-illusory reality effect. The narration is mostly a veiled pretense that, like the game's many anagrams, needs to be unjumbled and deciphered for information that can then be instrumentalized for the purpose of organizing a big sliding image tile puzzle and sorting syllables. It encourages the player to plunder its prose for encrypted data in search of not secret knowledge but secret treasure. The game and eventually the player is far more concerned with the deft interplay of these symbols qua symbols connecting and collecting within its own systems than the things the symbols usually gesture at.

Folks, we might have ourselves a hypertext here. It's borderline, but it's striking to me. Structurally, while there's no direct hyperlinks from one page to the next, the game's story is conceptualized as pages to be approached in arbitrary order. There is a final and proper canonical order, but filling in its gaps is itself a major overarching challenge. The classic logic of this-then-that narrative order and causality is invoked but obscured and its discovery is gamified. Pages are locked off by puzzle completion, and the pages you start with unlocked aren't all the first pages. Instead, the minigames pitch you hither and tither across the text, most often to the next page but just as likely clear into a different chapter. The narrative's been fragmented into episodic vignettes, and they often seemed to me to make just as much sense in that secondary order as in the primary order, like when I had a hard time with a puzzle and the next page unlocked began with The Fool also feeling exhausted from effort. You can read the last page right from the start, and the best straightforward explanation of what's going on and what you are to do is found in the similarly-available second-to-last chapter. Spiritually, there's also a distinct bent to the game where it's majorly concerned with connections and greedily gathering data points up, and delighted by the sheer architecture of its own semiotic house of mirrors, with only light concern if any for what it all adds up to or points at that ultimately makes it feel to me more "postmodern" (and hypertextual) than esotericist.

It's interesting just how much of a boom there is for node-based narrative here in the late 1980s. Partially that's an artifact of my selections, but I know for sure they're actually surprisingly sparse in the early 1980s. We've sadly seen the last Infocom game we're going to see on this blog already, but as the little-disputed critical and commercial leading light of text adventures recedes, we see not only the market but the texts themselves fragmenting — if you're even going to be considering this sort of thing as occupying the same aesthetic and niche that that sort of thing does as well at other times, which has become a fundamental guiding principle of the concept of "interactive fiction" but only as it was formulated through controversy. The parser norms of interactive fiction will reassert themselves in an Infocom-derived renaissance in the mid-90s, but then around the turn of the 2010s it zags back to hypertext again, possibly for good. Alternatively, if you see hypertext as something wholly separate from and even defined against the parser adventure game tradition, as The Fool's Errand suggests it to be, this was a savvy move from the parser camp to rhetorically capture and encompass a now-more-popular genre entirely within its own tradition. Either way, that makes this little interregnum feel like foreshadowing, all the moreso because a lot of these games are being made by people who come from backgrounds outside of gaming working solo or close to it who thereby have more offbeat perspectives and tones than the programmers we've been used to.

-------------

Thanks to Monkeysky for getting inspired to play the game at the same time as me so we could talk about it. Thanks to hypodronic for the recommendation of Lon Milo DuQuette's "Understanding Aleister Crowley's Thoth Tarot" — didn't bear much fruit for this article but did give me some sea legs.

This is the exact video game that inspired a NASCAR racer to ram his car up against the wall in the middle of the turn for an extremely video-game-in-real-life style speed boost a couple weeks ago. I remember coming to the exact opposite conclusion when I was a child: Every AI racer takes the outside of the curves, going up on the bank, because that's what you try to do in real life. That left the inside curve wide open, which even a 10 year old could tell you was geometrically shorter and thus a quicker route. Once I figured this out, I never once ranked under first place. I always figured that the reason this worked in the game but not in real life was that the game's physics weren't very realistic in some way with regards to banked turns, but the AI was programmed to behave as if it were to sell the illusion. Shows what I know! Apparently this game's physics in banked turns were more realistic than real life! This is why I'm not a NASCAR driver. Or maybe it's because I played PS2 and he played Gamecube...

This review contains spoilers

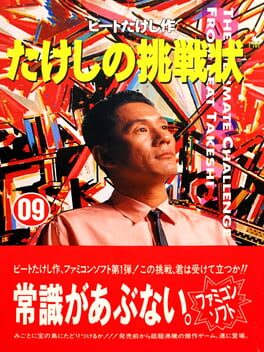

Nakayama Miho no Tokimeki High School [1987] is not one for the ages. It was made in either 3 months or start from finish in 2 weeks flat, depending on which interview you believe, immediately after Hironobu Sakaguchi finished work on Final Fantasy [1987], and right before Yoshio Sakamoto, creator of Metroid [1986], moved on to Famicom Detective Club: The Missing Heir [1988]. (There’s something deliciously perverse to me about covering this game as part of this canon without covering any of those more well-known ones.) It was meant to be disposable, transient junk food. It wasn’t even built to hang around later than February 1988. It is so deliberately tightly tied to its exact time and place, both by and from that exact cultural context. Integral to the game was its fax contest and automated telephone answering machines. While we can now play it while completely ignoring the first and substituting the second with a transcript of what you would have gotten if you called, we cannot write this all off as a mere sales gimmick easily disposed of. This aspect of the game was the germ of the whole rest of it, even preceding the idea of a licensed celebrity tie-in, and the telephone got co-star status on the cover with that same titular idol.

As you might have gathered from the remarkable paucity of J-Pop in the 1980s playlists, I must admit I am not very steeped in the cultural context this game comes out of — frankly, I don’t even grasp which order to put romanized Japanese names in, I just go along with what I see other writers doing — so I really hit the books for this one. The most important thing I was made to understand about idols is that, contrary to how I was thinking about it, the music is important but not central to either the workday of an idol nor the reception of the audience. Rather, idolhood is very multimedia, and many argue that its primary vector is not music but actually our old friend television. Its traditional doubled-edged qualities of its transient immediacy, its intimacy borne of inviting its characters into your living room and spending years regularly getting to know them, its industrial-scale replication of image, and its blurring of the lines between advertising and content are all expertly leveraged by the studios that manufacture idols, are key to the phenomena of the idol, and most of those qualities besides maybe the last are also in evidence at Tokimeki High School.

--- MUSICAL INTERMISSION: Nakayama Miho – Linne Magic [1987]

Unlike Takeshi Kitano’s relationship to Takeshi’s Challenge [1986], there is no pretense that Nakayama Miho had any creative input onto the game, any author function that dominates the text. Though they are both celebrities, there are different expectations of a middle-aged male comedian and actor and a teenaged girl pop singer and actress. Along with the gendered and age-based expectations, we expect unique perspective out of comedians, while a pop music audience is at peace with the idea that pop singers may very well sing a song they had nothing to do with making. (Nakayama Miho had only just written her first song in 1987.) It is readily apparent that she did a photoshoot for the game’s cover and its (very stylish) manual, some advertisements, lent her voice to the answering machines, and that’s probably the entire extent of her involvement. We are, basically, meant to understand Tokimeki High School as another story Nakayama Miho is acting in, even though she’s not actually being filmed performing.

And yet, somehow, the pitch of this game is that you the audience member will get to meet and spend time with the “real” Miho. We try to glimpse the authentic person through the manufactured media. This is the paradox of the star in general, AND of the simulation in general, and it’s this productive tension Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School is driven by. Its fictional premise is a kind of Hannah Montana [2006-2011] set-up: everyone knows of Nakayama Miho, pop idol, but she leads a double life as normal teenager Takayama Mizuho, courtesy of a pair of Clark Kent glasses. You (and the manual is very insistent that this player character is You, Full Stop,) attend the same high school as Mizuho, giving You privileged access to the “real” Miho.

This is only the beginning of what can be described as a postmodern hall of mirrors haunted by elusive phantoms. Not only are both Mizuho and Miho costumes worn for different social contexts in-fiction, they are both obviously equally fictional characters made from scratch out of pixels and words. Even that’s not the core truth of the matter, because whatever the material basis of image production is, it exists in concert and referent to Nakayama Miho, or more accurately the complex of other images the audience has of her. There is no center to orient yourself towards, just a complicated web of performances to parse. This reaches its dizzying heights when Miho leaves You a digital handwritten note to call a phone number to hear the actual Miho’s voice read from a script asking You out on a date with her virtual counterpart, in-character as Mizuho, to go see a fictional movie starring Miho as presumably yet another fictional character. She says she wants to experience her own movies from the perspective of a “normal” person, so she scripts this whole elaborate and extremely abnormal scenario and casts You in it as her scene partner. It’s as though the hope is that convoluting the matter as much as possible will somehow cut to the quick, will bamboozle you into living in the moment and not thinking about it too hard.

Nakayama Miho herself is easily the most complex character we’ve yet seen here in our walk through gaming history. Her only serious competition comes from the ranks of Deadline [1982], which I called at the time “a cast of untrustworthy stereotypes,” but who do have qualities that have nothing to do with the plot and interior personalities at conflict with themselves to be parsed. This game hinges on the particularities of Miho’s mood and mind, on careful attention to her television-sized close-ups and considering how she might feel.

…But complex doesn’t mean convincing. She has opinions and moods that come from vaguely the same place, but any illusion of an actual psychology is brutally punctured by the fact that, sooner or later, by design, you are going to have to brute-force your way through a conversation with her like she’s a combination lock. The skin peels off and you must see the gears and levers that actually constitute Miho. It’s nigh Brechtian.

Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School is shockingly linear. Prior adventure games we’ve seen heavily emphasized exploration, but the “move” option in this game simply brings you immediately to the next place where your character needs to be for the story to progress instead of having the player look for it. If there is something you have to see or do or stay, the story stays stuck right in place until you do it. The whole first act offers the player no choice in their actions or thoughts at all, except for those which have no ramifications like lingering for extra examination or dialogue. You have to swap the disk side three times before you get an actual branch point.

Even once the game opens up even a little, it prunes its tree very aggressively, leaving little room for variation in story until the endgame. It is just as linear, except now you can fail to walk the line. It’s deliberately cinematic, except the actors keep flubbing their lines so you have to take it from the top. You are, as ever, walking through an almost-invisible maze the developers built for you, divining its shape through bumping up against its edges when all else fails. There’s a scene where You get kidnapped by a girl in a white dress that recalls the “but thou must” scenes from Dragon Quest [1986], but with the dark twist that you know You really, really don’t want to say yes but all options that amount to “no,” while implemented, simply circle you back around to the question again.

Like Alter Ego [1986], this is a game based around choosing what You do next from its menu of options, and not one that is all that interested in the wide variety of possible paths that implies for either player self-expression or hypertextual contrast, but rather in taking a hard stance on the correct narrow path to follow with your life. It is, essentially, another didactic text with a distinct point of view about how a person, here a male teen, ought to comport themselves. It’s simulation as rehearsal, hence the repetition. For example, “touching” (groping) people or making a droolingly horny facial expression are offered as options but are always incorrect choices, inputs that are either quietly discarded or lead to a failstate or are openly chastised.

Walking its line gets stranger the further in you go, as it bends to fit the needs of a contrived plot. You get into a stupid dispute with Miho where neither You nor her are actually at fault, but you’re angry with her and she’s contrite, and the difficulty is that you actually aren’t offered the option to be upfront and forthright, or forgiving and ready to move on. The ultimate solution to how to patch up your relationship instead begins with making Miho start to cry. Then You insult her and act outraged, maximally seething, and only this course of action leads her to ask for your forgiveness and say she can’t bear the thought of never seeing You again. Through this route, she actually ends up saying the exact same lines verbatim which typically precede a game over, except this time You actually get to keep talking for no clear reason, and then You have to ask her “don’t you understand how I feel” while, importantly, not using any of the facial expressions that would actually indicate any feeling. What we are meant to glean about how to treat people from this hash is unclear at best and bad at worst.

It just seems like the game has a particular dramatic confrontation in mind and warps around it, in actually a pretty familiar and normal way to anyone who’s seen a kinda-lousy story where characters have no good reasons to be mad at each other, but the writers feel some kind of pressing need to gin up conflict from thin air as story grist, whilst also being too precious to actually have something go seriously awry. It’s a classic move of what I would say is just flat out classic bad storytelling, though there are many ways to recover from and redeem or forgive the beat, such as: making the irrationality part of the point, or giving some kind of reason for prolonged misunderstanding as in a farce, or just moving past the beat quickly enough that the audience doesn’t have time to get irritated and nit-picky about it. What Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School does instead is really dwell on it, and encourage the audience to deeply consider the emotions and logic of the scene, which seem more and more emotionally incoherent the longer the player goes over it. Instead of having the shape of the story and the things the player does in it determined by the formal structures of the game, they’ve gone and mounted a conventional story beat onto the adventure game trial-and-error framework which stretches it out until it rips apart.

This rehearsal dynamic is most easily navigated and clearly made apparent the first time the player has any effective choices at all, when they have their first substantial dialogue exchange with Mizuho/Miho, having just figured out the double-act. You get a bunch of A/B choices of what to say, and the choice is typically whether or not to talk about Miho’s celebrity status. Throughout the whole game, Miho gets really touchy and visibly angry if You ever bring up her job, and if you persist you head right to a game over. (In a shocking generosity for the era, this game has you start scenes over if you fail instead of the entire game.) The message is clear and agreeable: if you happen to meet a celeb in the flesh, just treat them like a normal person, don’t geek out.

However, this means the game exists in a sustained state of self-denial. The whole reason we are here, in and out of fiction, is that we are interested in Nakayama Miho due to her celebrity. But we must constantly dance around the subject, never addressing the facts head-on except when the game takes over for us. In fact, we are actively confronted with the possibility of speaking honestly and then quite deliberately suppressing it. The A/B choices demand to be read not as opposing pairs but in superposition and synthesis, as running commentary on one another, the polite conscious and the basal unconscious, each simultaneously possible and possibly simultaneous. This is the split personality of Miho/Mizuho, mechanized.

There’s actually a lot more significant pairs in the cast. The rich snob girl, Erika, and the rich snob boy, Masaomi. The strict vice principal, and the cuddly principal. The trio of Erika’s sycophants, and the trio of adult male thugs who work for Erika. There’s another character, Sadakichi, who’s your Mizuho — your shadow. Especially in the early game, he tags along making observations that your character cannot because your character is meant to be You, and You don’t know the kids at this new school. He has the same fannish predilections as You, but he is not as lucky, always a moment too late, so that You get to the plot first. His chubby looks are an object of ridicule from the first lines of the game, which marks him out permanently as someone who does not get to participate in romance or desire. Besides that, the game seems reasonably endeared of him. He gets a cool motorcycle! Sadakichi is at once a model of the ideal consumer audience and stigmatized.

Sex is also pointedly repressed and denied. It’s broached twice in the first act. Once, You run into the vice principal, an absolute tightwad, who gets embarrassed when You discover him carrying a porno mag around in his vest. It’s a natural tidy irony: the guy droning on and on about propriety and procedure is just poorly suppressing his own sleaziness and trying to do extend that same censorious attitude to everyone else. Secondly, and earlier, right before Your very first spoken exchange with Miho, while You’re just looking for the girl who dropped something when You bumped into her, Sadakichi hears some girls in a classroom and thinks that might be who you’re looking for. So, You peek in, and surprise: it’s two teen girls in their underwear getting dressed in a classroom after school for some reason! Miho shows up immediately after this shot for the second time, the first where You actually get to conversate with her at all.

This is… less natural and tidy. It’s a PG-13 riff on a gag I’d more expect in a bawdy college sex comedy of this era than the achingly chaste soap-operatic high school rom com this game otherwise is. It’s not entirely clear to me why it’s here, so pardon me while I overthink one ultimately insignificant shot while not even mentioning entire characters and subplots. It’s a wide shot with big bugged-out eyes, clearly more comically awkward than gratuitously titillating, but it’s not particularly funny because there’s no development of the premise towards any kind of point at all. Because it’s an honest accident around an inexplicable situation, it doesn’t really reflect on anyone’s decisions and thus doesn’t, say, characterize either Sadakichi or the player character as a bit of a sleaze. Because it’s so unpredictable, maybe it’s meant to juice the rest of the game with a certain charge; if not an erotic one, then one where any random thing could be around the next blind corner. Maybe it’s there because a frazzled attitude around sex is part of being 17. The language of cinematic montage connects this image directly with the appearance of Miho. This can either be interpreted 1) as supplementary — “for all their gentlemanly behavior, boys only have one thing on their mind when it comes to cute girls,” that though this is an accident it still formally commentates on the boys’ goals or unconscious desires, like the A/B choices — or 2) as contrast — this is not a game where you will be seeing Miho in her underwear, that’s for certain: not only is she a real-life 17-year-old celebrity, but by immediately following something a little prurient with polite navigation of choppy conversational waters you can argue it’s signalling to the audience that this story isn’t THAT, it’s THIS. Indeed, your relations with her are to be so very chaste that You don’t even get to successfully kiss before the end of the game.

Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School is often-enough cited as the first proper dating sim: The meat of the gameplay revolves around navigating dialog trees, and though that sounds pedestrian enough now, this is actually the first we’re seeing of it on this blog, though it’s not a new thing in 1987 Japan, and the ultimate goal of navigating these dialog trees is to master interpersonal social behavior such that You can successfully secure and perform dates with a virtual girl whose emotional state is tracked and displayed in some detail. I’m not a subject matter expert so I won’t make that genre call for myself, and besides, it’s not as though they sat down to make a dating sim because that concept didn’t exist yet so it could hardly inform its shape. Its clearest historical influence is once again from the Portopia Serial Murder Case [1983/1985] lineage. Portopia even has phone calls to gate progression!

However, there is another lineage of Japanese computer adventure games, the one I already mentioned back in that article: the pornos. An accidental-peeping-Tom scene would have a pretty obvious reason to be in one of those, maybe that’s what’s being expressly denied. History happened over there too, porn games didn’t sit still for 4 years either, and as best as I can tell they beat this game to the punch on the whole dialog-tree-navigation gameplay by about a year or two in titles like Kudokikata Oshiemasu [1986]. It’s not certain, but it’s certainly not impossible that that’s where the designers lifted the concept from: Sakaguchi and Square as a whole got their start in the computer adventure-gaming market, with their last computer game before working on consoles, Alpha [1986], having some softcore erotic elements. Perhaps Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School brings up and denies pornography as an allusion, a head nod, but that’s a pretty strong and spicy claim to be backed up by no evidence whatsoever, so let’s just call it a rhyme. Regardless, the dating sim and the porn game would remain strongly associated into the future, giving even chaste rom-coms like these a whiff of dirty and disreputable salaciousness that dogs the genre to this day.

-----

Originally posted on my blog, [https://arcadeidea.wordpress.com/2022/06/27/nakayama-miho-no-tokimeki-high-school-1987/](Arcade Idea.)

As you might have gathered from the remarkable paucity of J-Pop in the 1980s playlists, I must admit I am not very steeped in the cultural context this game comes out of — frankly, I don’t even grasp which order to put romanized Japanese names in, I just go along with what I see other writers doing — so I really hit the books for this one. The most important thing I was made to understand about idols is that, contrary to how I was thinking about it, the music is important but not central to either the workday of an idol nor the reception of the audience. Rather, idolhood is very multimedia, and many argue that its primary vector is not music but actually our old friend television. Its traditional doubled-edged qualities of its transient immediacy, its intimacy borne of inviting its characters into your living room and spending years regularly getting to know them, its industrial-scale replication of image, and its blurring of the lines between advertising and content are all expertly leveraged by the studios that manufacture idols, are key to the phenomena of the idol, and most of those qualities besides maybe the last are also in evidence at Tokimeki High School.

--- MUSICAL INTERMISSION: Nakayama Miho – Linne Magic [1987]

Unlike Takeshi Kitano’s relationship to Takeshi’s Challenge [1986], there is no pretense that Nakayama Miho had any creative input onto the game, any author function that dominates the text. Though they are both celebrities, there are different expectations of a middle-aged male comedian and actor and a teenaged girl pop singer and actress. Along with the gendered and age-based expectations, we expect unique perspective out of comedians, while a pop music audience is at peace with the idea that pop singers may very well sing a song they had nothing to do with making. (Nakayama Miho had only just written her first song in 1987.) It is readily apparent that she did a photoshoot for the game’s cover and its (very stylish) manual, some advertisements, lent her voice to the answering machines, and that’s probably the entire extent of her involvement. We are, basically, meant to understand Tokimeki High School as another story Nakayama Miho is acting in, even though she’s not actually being filmed performing.

And yet, somehow, the pitch of this game is that you the audience member will get to meet and spend time with the “real” Miho. We try to glimpse the authentic person through the manufactured media. This is the paradox of the star in general, AND of the simulation in general, and it’s this productive tension Nakayama Miho No Tokimeki High School is driven by. Its fictional premise is a kind of Hannah Montana [2006-2011] set-up: everyone knows of Nakayama Miho, pop idol, but she leads a double life as normal teenager Takayama Mizuho, courtesy of a pair of Clark Kent glasses. You (and the manual is very insistent that this player character is You, Full Stop,) attend the same high school as Mizuho, giving You privileged access to the “real” Miho.

This is only the beginning of what can be described as a postmodern hall of mirrors haunted by elusive phantoms. Not only are both Mizuho and Miho costumes worn for different social contexts in-fiction, they are both obviously equally fictional characters made from scratch out of pixels and words. Even that’s not the core truth of the matter, because whatever the material basis of image production is, it exists in concert and referent to Nakayama Miho, or more accurately the complex of other images the audience has of her. There is no center to orient yourself towards, just a complicated web of performances to parse. This reaches its dizzying heights when Miho leaves You a digital handwritten note to call a phone number to hear the actual Miho’s voice read from a script asking You out on a date with her virtual counterpart, in-character as Mizuho, to go see a fictional movie starring Miho as presumably yet another fictional character. She says she wants to experience her own movies from the perspective of a “normal” person, so she scripts this whole elaborate and extremely abnormal scenario and casts You in it as her scene partner. It’s as though the hope is that convoluting the matter as much as possible will somehow cut to the quick, will bamboozle you into living in the moment and not thinking about it too hard.

Nakayama Miho herself is easily the most complex character we’ve yet seen here in our walk through gaming history. Her only serious competition comes from the ranks of Deadline [1982], which I called at the time “a cast of untrustworthy stereotypes,” but who do have qualities that have nothing to do with the plot and interior personalities at conflict with themselves to be parsed. This game hinges on the particularities of Miho’s mood and mind, on careful attention to her television-sized close-ups and considering how she might feel.

…But complex doesn’t mean convincing. She has opinions and moods that come from vaguely the same place, but any illusion of an actual psychology is brutally punctured by the fact that, sooner or later, by design, you are going to have to brute-force your way through a conversation with her like she’s a combination lock. The skin peels off and you must see the gears and levers that actually constitute Miho. It’s nigh Brechtian.