SlayerSaint

75 Reviews liked by SlayerSaint

MultiVersus

2022

Mortal Kombat 1

2023

Story is yet another in the oversaturated multiverse plot market these days.

But man oh man is the gameplay a few steps up from MK11. Combos can go on forever sometimes, but it still feels a lot more accessible than MKX's cracked gameplay these days.

The biggest downside is how hard they've leaned into microtransactions this iteration. Spending real money to unlock fatalities with no other option for doing so is beyond appalling. The skins you can unlock through normal gameplay are by and large ham-handed recolors of the same 2-3 outfits, and the ones that are actually cosmetically different cost real money, too. That wouldn't be so bad if not for everything that costs real money requiring you to buy more than that amount in the Dragon Krystal currency, as is the norm in games these days it seems.

Overall, though, I can continue to enjoy Mortal Kombat gameplay that isn't severely watered down, which is the main thing I play these games for.

But man oh man is the gameplay a few steps up from MK11. Combos can go on forever sometimes, but it still feels a lot more accessible than MKX's cracked gameplay these days.

The biggest downside is how hard they've leaned into microtransactions this iteration. Spending real money to unlock fatalities with no other option for doing so is beyond appalling. The skins you can unlock through normal gameplay are by and large ham-handed recolors of the same 2-3 outfits, and the ones that are actually cosmetically different cost real money, too. That wouldn't be so bad if not for everything that costs real money requiring you to buy more than that amount in the Dragon Krystal currency, as is the norm in games these days it seems.

Overall, though, I can continue to enjoy Mortal Kombat gameplay that isn't severely watered down, which is the main thing I play these games for.

Pretty good pizzeria simulator. But in all seriousness pretty good Five Night's at Freddy's game not my favorite but still pretty good. I really enjoyed decorating my own pizzeria. I also liked most of the minigames and the lore hidden within some of them. I also had a lot of fun getting all the endings.

Palworld

2024

One of the creepiest looking Five Nights at Freddy's games to date. Unfortunately it's also one of the easiest which is made even more unfortunate because Springtrap has one of the eeriest and coolest looking designs in the entire franchise in my opinion.

Side note: Activating the minigames is really weird and didn't always work for me.

Side note: Activating the minigames is really weird and didn't always work for me.

One of the best Five Nights at Freddy's games. I mean what else is there to say it's a classic. I really like the level design in this one it's not to overwhelming unlike the second one. The animatronic designs are pretty cool as well and while they may not be the scariest. They look like they belong in a children's pizzeria which fits the story/lore nicely.

Better than the first game. I love the ties between this DLC's story and the main game. I had lots of fun and strived to collect all the collectibles just like the main game. This DLC's atmosphere is even eerier than the first one. Also the antagonists hunting you down were so much better. Also this game truly made me never want to have kids. The miracle of birth my ass. This DLC like the main game also had plenty of WTF moments possibly even more than the first.

Side note: Fuck Eddie Gulkskin/The Groom good antagonist... But nope nope absolutely not.

Side note: Fuck Eddie Gulkskin/The Groom good antagonist... But nope nope absolutely not.

Outlast

2013

I really enjoyed my time with Outlast and it was a blast. It had an unnerving atmosphere which added to scare factor and kept me on my toes. I love the found footage style of the game especially the night vision mode. My main gripe is that I wish the main game was longer. This is also one of the only games where I strived to get all the collectibles for fun. There were also a lot of WTF moments littered throughout. Which for me personally made the game that much more enjoyable. It definitely had it's fair share of glitches but honestly most of them were pretty funny.

Overcooked is a fun game as long as you have a friend to play with by yourself it is extremely boring and lackluster experience. Playing with a friend can be a good way to have a lot of fun, chaos and yelling at one another about who needs to do what. While I do enjoy this game and the friendships it has tested I've had some performance issues on the Nintendo switch.

The games included in this Jackbox Party Pack are some of my personal favorites and are an absolute blast with the right group of friends or even family. My favorites from this pack are Tee K.O. and Murder Trivia Party. They are the games in my personal opinion to have the most chaos in the best possible ways. I look forward to playing them with friends and family again.

Alan Wake

2010

I decided to play Alan Wake before playing Alan Wake 2 and I absolutely loved it. I was constantly engaged and really enjoyed the story and I never once felt bored. It was a thrilling and fun ride all the way through. However it being an Xbox 360 game originally made the controls feel very clunky and sluggish at times. There were times whenever I would be running and let go of the run button that Alan would keeping running which led to several incidents of him running of a cliff causing me to die. There were a few glitches here and there but nothing to major or game breaking. It's now one of my favorite games and I'm really excited to see how the story of Alan Wake 2 will play out. Although I did knock off half a point for the clunky and sluggish controls. Overall it's a game I would highly recommend.

Killer Frequency

2023

I really enjoyed this game even though some of the puzzles felt repetitive. It's a great game if you enjoy 80's horror comedy and dad jokes. For me personally, it was the the perfect amount of campiness, Although the protagonist radio host voice sometimes got on my nerves. Overall I would recommend to those who like this style of game.

Devil May Cry 2

2012

Just don't. I would highly recommend skipping this entry in the Devil May Cry series. Some of my personal gripes with this entry is that it is way to easy I beat in within 4 hours. Plus I only ever used Ebony and Ivory for the entire game. There was no incentive to use anything else guns are op in this game. The bosses are defiantly the worst in the series. It's overall level design also left a lot to be desired. And why I understand why Dante isn't is normal goofy cheeky self It made the overall atmosphere that much worse. The only redeeming quality of this game is Dante's outfit design.

Palworld

2024

IMO, not nearly as bad as some people would like to tell you it is but almost certainly the definition of "Early Access". I enjoy the Blegends Blarceus-esque gameplay, I like the Pal designs I've encountered, some much more than comparable creatures from That other series, and Zoe is an absolute baddie...

...but it's very technically shaky and clearly missing a lot of the meat on the bones, so I have to put it on pause for now 'til release, since I'm not the biggest fan of Ark and its' ilk, even if I enjoy how Palworld specifically handles it. For the people that LOVE those kinds of games and can work through their technical issues and set their own crazy goals I see them getting hooked on this shit.

All that said, isn't it kind of crazy this is the only Blokemon game that actually has natures and personality traits that make each individual Pal a little more unique like the original series???

...but it's very technically shaky and clearly missing a lot of the meat on the bones, so I have to put it on pause for now 'til release, since I'm not the biggest fan of Ark and its' ilk, even if I enjoy how Palworld specifically handles it. For the people that LOVE those kinds of games and can work through their technical issues and set their own crazy goals I see them getting hooked on this shit.

All that said, isn't it kind of crazy this is the only Blokemon game that actually has natures and personality traits that make each individual Pal a little more unique like the original series???

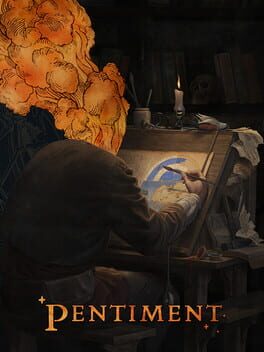

Pentiment

2022

‘This was the only earthly love of my life, and I could not, then or ever after, call that love by name.’

– Umberto Eco, Il nome della rosa, 1980.

Capturing the contours of a sixteenth-century society in the Holy Roman Empire is a difficult task. Central Europe was undergoing complex transitions as a result of demographic recovery, religious innovation and the administrative mosaic of Germanic territories. Recent historiography emphasises the interlocking and overlapping of forces that shaped regions and societies: it is difficult to generalise local observations to the rest of the Empire, but it is also unwise to paint the portrait of a village on the basis of generalities alone. For example, the forms of feudalism differed on either side of the Elbe. A theoretical simplification is to consider the regions south and west of the Elbe as being under the rule of Grundherrschaft [1]. This form of feudalism developed from the 14th century onwards with the decline of the traditional smaller lords and the demographic collapse caused by the Black Death. This situation allowed the surviving peasants to expand their farms and establish stronger hereditary rights over the land. Although still subject to the authority of their local lord, they had greater freedom of action.

History, fiction and myth: the Umbertian gaze

Towards the end of the fifteenth century, friction between the nobility and the peasantry increased as the former sought to assert their authority over land that seemed to have been de facto freed from serfdom. Another factor in the social crisis was undoubtedly the demographic upturn from 1470 onwards, which swelled the cohort of landless peasants, while small landowners were no longer able to take advantage of the economic opportunities of the previous century. In some southern regions of the Holy Roman Empire, agricultural production was no longer profitable, so it became mainly subsistence farming. These factors led to a widening gap between the peasants and the lords. The lords, sometimes nobility, sometimes clergy, were in latent conflict for other economic and political reasons.

It is difficult to summarise several thousand pages of social history in a few lines, so these few elements of context will suffice. Pentiment makes the bold choice of setting its action in this complex historical background, in a locality centred around the village of Tassing and Kiersau Abbey. The project explicitly borrows from Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose (1980). Although the historical context is different, the themes and structure are similar. Eco's readers will find themselves in familiar territory: Pentiment allows the player to assume the role of Andreas Maler, a Nuremberg artist commissioned by the Abbot of Kiersau to illustrate a Book of Hours as part of his certification as a master artist. During his stay in Tassing, Andreas gets to know the many members of the local society, until a murder takes place. For personal reasons, Andreas is thrust into the role of detective and must unravel the many secrets of the community.

Like The Name of the Rose, Pentiment multiplies points of view and semantic layers. The game is at once a general dissertation on the social history of the Holy Roman Empire, a detective story, a philosophical debate, a theological meditation and a discussion on the value of storytelling. It is through this literary device, borrowed from Eco, that the title manages to find a great deal of coherence in its storytelling [2]. The investigation – i.e. the criminal story – is interwoven with the socio-political narrative, so that the player is constantly confronted with both general and specific elements. Andreas Maler acts as a bridge between these two worlds. Firstly, because he finds himself at the crossroads of very different social universes: as a traveller, he is used to many cultures; as a young artist, he associates with the powerful without being fully part of their universe. Above all, he is a stranger to Tassing, and his gaze is that of a witness whose interest in local politics, however altruistic, is rather weak. In other words, his view is certainly subjective, but it is all-encompassing. These characteristics are very similar to those of William of Baskerville, who had a complex theological background.

Depicting the Middle Ages through the new social studies

In terms of narrative economy, such a protagonist captures the player's attention in a number of ways. For classically trained historians, Andreas provides access to the ancient and medieval literary world; for mystery fans, his role as a detective is crucial. The choice of Andreas' background means that, in addition to the interactive gameplay typical of CRPGs, players can personalise their experience around the themes that interest them most. As a Latinist, I was pleasantly surprised to see Pentiment commanding a very solid Latin, and to read the classical locutions quoted by Andreas. The title has a rare encyclopaedic quality, in tune with recent scholarly developments. There remain a few very minor approximations, such as certain onomastic choices (Else Mülleryn should rather be spelt Müllerin) and Kiersau's remarkable and exagerated interregionalism. On the latter point, the choice was certainly motivated by Umberto Eco's vision of a universalist abbey and a political response to Kingdom Come: Delivrance (2018): the figure of the Ethiopian priest Sebhat seems a rather explicit foil to Daniel Vávra's ultra-conservative claims about the absence of people of colour in fifteenth-century Bohemia.

Pentiment always uses its encyclopaedic knowledge wisely to illustrate medieval mentalities. Arrogantly imparting knowledge is the best way to undermine the friendship and support of the game's various characters. The game constantly seeks to highlight the limits of Andreas' knowledge and the subjectivity of the concept of truth. As such, Pentiment seeks to portray the situation of women in the Middle Ages with real nuance. The game's fictional micro-history project features women who are involved in their village's economy and are pillars of the community. Discussions with the Benedictine nuns also provide an opportunity to explore women in religion, and Pentiment clearly illustrates the prejudices of the time, as well as Andreas' very masculine perspective. In contrast to the Christian tradition, which leaves no place for women in its traditional hierarchy – women's religious offices generally disappeared in the central Middle Ages, which is exactly the situation described for Kiersau Abbey – and restricts them to religious life or marriage, Pentiment constantly emphasises their agency and the ways in which they can circumvent the restrictions. Amalie illustrates the extreme spiritual experiences that women can voluntarily inflict on themselves through her retreat and mystical visions. Illuminata embodies a mastery of the literary classics, while the other sisters stand out for their practical knowledge and integration into Tassing society.

To write, to read and to die in the universal library

Like Umberto Eco's library, that of Kiersau Abbey is intended to be universal. It seeks to circumscribe all known knowledge through the possession of rare volumes, be they erudite treatises or chivalric romances. Writing and rewriting are at the heart of Pentiment's project. The narrative is subjective and subject to numerous corrections: when the dialogue is presented, mistakes punctuate the text and are corrected in front of the player. Similarly, the choice of script depends on the impression the speaker makes on Andreas. He presents the discourse of the educated clergy in a Gothic style, while the villagers have a much less polished script. Above all, it is noteworthy that Andreas changes his representation according to the information he receives. For example, when he learns that the shepherd is actually an avid reader of Latin books, he updates the script used in the dialogue. These elements are linked to a concern for memory, and Pentiment sets out to question what deserves to be left to posterity, rejecting the idea of a monolithic history. The truth is in a constant state of flux and varies from different perspectives: it is this insight that guides Andreas' investigation into the various murders. The game is less about finding the culprit than about writing Tassing's story. The game forces the player to accuse one of the suspects for each murder, but it is remarkable that all the solutions seem unsatisfactory. Pentiment is not about solving murders, but about understanding how Tassing society reacts to events that upset its internal balance.

Pentiment borrows its idea of humour from The Name of the Rose [3]: laughter is used to subvert the order of the world, because it reveals – through sarcasm or astonishment – the way in which the world turns. The comic scenes in the game anchor the narrative in a plausible reality, not just a cold, theoretical illustration of 16th-century Tassing. Pentiment's dialogue system is not so much a mechanic that supports 'choices' leading to different endings, but rather a sincere exploration of the world. Comedy is necessary because it is an instrument of freedom and truth, which all the characters seek in one way or another: to laugh is to break free from social bonds, hence Saint Grobian's irreverence. Conversely, silence allows the player to conform to the social mould, to maintain the status quo. Such a position is sometimes necessary to make progress in an investigation without alienating potential allies. The great strength of Pentiment is that it strikes the right balance between laughter, speech and silence. The characters, including Andreas, have to take a stand, and the question is how to do it.

There are no straightforward answers, and the game is never preachy or pretentious. The complexity of the world, of social relations and social transformations explain the hesitations. Uncertainty is part of the truth: Pentiment shines through its unique artistic direction, borrowed from manuscripts and engravings. In a stroke of genius, the game moves drawn characters on fixed backgrounds. There's something magical about seeing sketches move in this way, evoking a kind of collage. The practice of cutting out and reusing figures and backgrounds is well documented in the production of medieval manuscripts, underlining the plasticity of art in the representation of history [4]. In a fifteen-hour adventure, Pentiment creates such a vast universe. I find it difficult to write more, given the extraordinary richness so elegantly condensed into a game, from religious issues to economic innovations. In this respect, it is worth mentioning the welcome presence of an indicative bibliography in the game's credits. Umberto Eco concludes The Name of the Rose with a variation on a line by Bernard of Cluny: 'Stat rosa pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus', he writes. The original rose lives on in its name, we keep the names naked. To Bernard of Cluny's 'ubi sunt...?', Eco adds the persistence of memory. The memory of people who existed centuries ago should persist even more; Pentiment is a sublime fresco in their honour, coming as close as possible to the historical truth without ever being able to fully circumscribe it: 'Since I tell to its end my story, then joyful shall be my days.' [5]

___________

[1] Joachim Whaley, 'Economic Landscapes, Communities, and their Grievances', in Germany and the Holy Roman Empire, vol. 1, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012, pp. 122-142.

[2] José-Marie Cortès, 'Itinéraires interprétatifs dans Le Nom de la Rose', in Synergies Inde, no. 2, 2007, pp. 289-306.

[3] Michel Perrin, 'Problématique du rire dans Le Nom de la Rose d'Umberto Eco (1980) : de la Bible au XXe siècle', in Bulletin de l'Association Guillaume Budé, no. 58, 1999, pp. 463-477.

[4] Anna Dlabacová, ‘Medieval Photoshop’, on leidenmedievalistsblog.nl, 18th February 2022, consulted on 13th June 2023.

[5] Wolfram von Eschenback, Parzival, II, XVI, l. 676 (trans. Jessie L. Weston), c. 1210.

– Umberto Eco, Il nome della rosa, 1980.

Capturing the contours of a sixteenth-century society in the Holy Roman Empire is a difficult task. Central Europe was undergoing complex transitions as a result of demographic recovery, religious innovation and the administrative mosaic of Germanic territories. Recent historiography emphasises the interlocking and overlapping of forces that shaped regions and societies: it is difficult to generalise local observations to the rest of the Empire, but it is also unwise to paint the portrait of a village on the basis of generalities alone. For example, the forms of feudalism differed on either side of the Elbe. A theoretical simplification is to consider the regions south and west of the Elbe as being under the rule of Grundherrschaft [1]. This form of feudalism developed from the 14th century onwards with the decline of the traditional smaller lords and the demographic collapse caused by the Black Death. This situation allowed the surviving peasants to expand their farms and establish stronger hereditary rights over the land. Although still subject to the authority of their local lord, they had greater freedom of action.

History, fiction and myth: the Umbertian gaze

Towards the end of the fifteenth century, friction between the nobility and the peasantry increased as the former sought to assert their authority over land that seemed to have been de facto freed from serfdom. Another factor in the social crisis was undoubtedly the demographic upturn from 1470 onwards, which swelled the cohort of landless peasants, while small landowners were no longer able to take advantage of the economic opportunities of the previous century. In some southern regions of the Holy Roman Empire, agricultural production was no longer profitable, so it became mainly subsistence farming. These factors led to a widening gap between the peasants and the lords. The lords, sometimes nobility, sometimes clergy, were in latent conflict for other economic and political reasons.

It is difficult to summarise several thousand pages of social history in a few lines, so these few elements of context will suffice. Pentiment makes the bold choice of setting its action in this complex historical background, in a locality centred around the village of Tassing and Kiersau Abbey. The project explicitly borrows from Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose (1980). Although the historical context is different, the themes and structure are similar. Eco's readers will find themselves in familiar territory: Pentiment allows the player to assume the role of Andreas Maler, a Nuremberg artist commissioned by the Abbot of Kiersau to illustrate a Book of Hours as part of his certification as a master artist. During his stay in Tassing, Andreas gets to know the many members of the local society, until a murder takes place. For personal reasons, Andreas is thrust into the role of detective and must unravel the many secrets of the community.

Like The Name of the Rose, Pentiment multiplies points of view and semantic layers. The game is at once a general dissertation on the social history of the Holy Roman Empire, a detective story, a philosophical debate, a theological meditation and a discussion on the value of storytelling. It is through this literary device, borrowed from Eco, that the title manages to find a great deal of coherence in its storytelling [2]. The investigation – i.e. the criminal story – is interwoven with the socio-political narrative, so that the player is constantly confronted with both general and specific elements. Andreas Maler acts as a bridge between these two worlds. Firstly, because he finds himself at the crossroads of very different social universes: as a traveller, he is used to many cultures; as a young artist, he associates with the powerful without being fully part of their universe. Above all, he is a stranger to Tassing, and his gaze is that of a witness whose interest in local politics, however altruistic, is rather weak. In other words, his view is certainly subjective, but it is all-encompassing. These characteristics are very similar to those of William of Baskerville, who had a complex theological background.

Depicting the Middle Ages through the new social studies

In terms of narrative economy, such a protagonist captures the player's attention in a number of ways. For classically trained historians, Andreas provides access to the ancient and medieval literary world; for mystery fans, his role as a detective is crucial. The choice of Andreas' background means that, in addition to the interactive gameplay typical of CRPGs, players can personalise their experience around the themes that interest them most. As a Latinist, I was pleasantly surprised to see Pentiment commanding a very solid Latin, and to read the classical locutions quoted by Andreas. The title has a rare encyclopaedic quality, in tune with recent scholarly developments. There remain a few very minor approximations, such as certain onomastic choices (Else Mülleryn should rather be spelt Müllerin) and Kiersau's remarkable and exagerated interregionalism. On the latter point, the choice was certainly motivated by Umberto Eco's vision of a universalist abbey and a political response to Kingdom Come: Delivrance (2018): the figure of the Ethiopian priest Sebhat seems a rather explicit foil to Daniel Vávra's ultra-conservative claims about the absence of people of colour in fifteenth-century Bohemia.

Pentiment always uses its encyclopaedic knowledge wisely to illustrate medieval mentalities. Arrogantly imparting knowledge is the best way to undermine the friendship and support of the game's various characters. The game constantly seeks to highlight the limits of Andreas' knowledge and the subjectivity of the concept of truth. As such, Pentiment seeks to portray the situation of women in the Middle Ages with real nuance. The game's fictional micro-history project features women who are involved in their village's economy and are pillars of the community. Discussions with the Benedictine nuns also provide an opportunity to explore women in religion, and Pentiment clearly illustrates the prejudices of the time, as well as Andreas' very masculine perspective. In contrast to the Christian tradition, which leaves no place for women in its traditional hierarchy – women's religious offices generally disappeared in the central Middle Ages, which is exactly the situation described for Kiersau Abbey – and restricts them to religious life or marriage, Pentiment constantly emphasises their agency and the ways in which they can circumvent the restrictions. Amalie illustrates the extreme spiritual experiences that women can voluntarily inflict on themselves through her retreat and mystical visions. Illuminata embodies a mastery of the literary classics, while the other sisters stand out for their practical knowledge and integration into Tassing society.

To write, to read and to die in the universal library

Like Umberto Eco's library, that of Kiersau Abbey is intended to be universal. It seeks to circumscribe all known knowledge through the possession of rare volumes, be they erudite treatises or chivalric romances. Writing and rewriting are at the heart of Pentiment's project. The narrative is subjective and subject to numerous corrections: when the dialogue is presented, mistakes punctuate the text and are corrected in front of the player. Similarly, the choice of script depends on the impression the speaker makes on Andreas. He presents the discourse of the educated clergy in a Gothic style, while the villagers have a much less polished script. Above all, it is noteworthy that Andreas changes his representation according to the information he receives. For example, when he learns that the shepherd is actually an avid reader of Latin books, he updates the script used in the dialogue. These elements are linked to a concern for memory, and Pentiment sets out to question what deserves to be left to posterity, rejecting the idea of a monolithic history. The truth is in a constant state of flux and varies from different perspectives: it is this insight that guides Andreas' investigation into the various murders. The game is less about finding the culprit than about writing Tassing's story. The game forces the player to accuse one of the suspects for each murder, but it is remarkable that all the solutions seem unsatisfactory. Pentiment is not about solving murders, but about understanding how Tassing society reacts to events that upset its internal balance.

Pentiment borrows its idea of humour from The Name of the Rose [3]: laughter is used to subvert the order of the world, because it reveals – through sarcasm or astonishment – the way in which the world turns. The comic scenes in the game anchor the narrative in a plausible reality, not just a cold, theoretical illustration of 16th-century Tassing. Pentiment's dialogue system is not so much a mechanic that supports 'choices' leading to different endings, but rather a sincere exploration of the world. Comedy is necessary because it is an instrument of freedom and truth, which all the characters seek in one way or another: to laugh is to break free from social bonds, hence Saint Grobian's irreverence. Conversely, silence allows the player to conform to the social mould, to maintain the status quo. Such a position is sometimes necessary to make progress in an investigation without alienating potential allies. The great strength of Pentiment is that it strikes the right balance between laughter, speech and silence. The characters, including Andreas, have to take a stand, and the question is how to do it.

There are no straightforward answers, and the game is never preachy or pretentious. The complexity of the world, of social relations and social transformations explain the hesitations. Uncertainty is part of the truth: Pentiment shines through its unique artistic direction, borrowed from manuscripts and engravings. In a stroke of genius, the game moves drawn characters on fixed backgrounds. There's something magical about seeing sketches move in this way, evoking a kind of collage. The practice of cutting out and reusing figures and backgrounds is well documented in the production of medieval manuscripts, underlining the plasticity of art in the representation of history [4]. In a fifteen-hour adventure, Pentiment creates such a vast universe. I find it difficult to write more, given the extraordinary richness so elegantly condensed into a game, from religious issues to economic innovations. In this respect, it is worth mentioning the welcome presence of an indicative bibliography in the game's credits. Umberto Eco concludes The Name of the Rose with a variation on a line by Bernard of Cluny: 'Stat rosa pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus', he writes. The original rose lives on in its name, we keep the names naked. To Bernard of Cluny's 'ubi sunt...?', Eco adds the persistence of memory. The memory of people who existed centuries ago should persist even more; Pentiment is a sublime fresco in their honour, coming as close as possible to the historical truth without ever being able to fully circumscribe it: 'Since I tell to its end my story, then joyful shall be my days.' [5]

___________

[1] Joachim Whaley, 'Economic Landscapes, Communities, and their Grievances', in Germany and the Holy Roman Empire, vol. 1, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012, pp. 122-142.

[2] José-Marie Cortès, 'Itinéraires interprétatifs dans Le Nom de la Rose', in Synergies Inde, no. 2, 2007, pp. 289-306.

[3] Michel Perrin, 'Problématique du rire dans Le Nom de la Rose d'Umberto Eco (1980) : de la Bible au XXe siècle', in Bulletin de l'Association Guillaume Budé, no. 58, 1999, pp. 463-477.

[4] Anna Dlabacová, ‘Medieval Photoshop’, on leidenmedievalistsblog.nl, 18th February 2022, consulted on 13th June 2023.

[5] Wolfram von Eschenback, Parzival, II, XVI, l. 676 (trans. Jessie L. Weston), c. 1210.