Erato_Heti

3120 Reviews liked by Erato_Heti

I commend their efforts to try and convert DDR to the game boy color, but there's not a lot here. The setlist is comprised of various songs from DDRs 1 and 2 converted to work on the game boy color's sound chip, and honestly the music isn't bad. Sometimes it sounds a bit shrill, but for the most part my preexisting knowledge of the songs from the main games was able to fill in the blanks left by the chiptune covers. There are even more songs here than the first DDR game so that's also something.

My main problem here is the control scheme, but I can't really fault anything but the system that this is on for that. Due to the fact you can't push opposite cardinal directions on a D-pad plus the GBC only having 2 face buttons it do mean that A is right and B is up and u just gotta play it like that. They did make a finger-sized pad that can go over the GBC, bless their heart, but it still probably isn't the most optimal IMO. And yes, I was insane enough to try hooking this up to the gamecube game boy player to see if I could play it with a gamecube DDR pad. It unfortunately didn't work as the game still doesn't know how to detect both cardinal directions from the D-pad at the same time. Can't really fault them for that one ngl.

I guess the point of this is to practice the rhythmic patterns and maps for various DDR songs so that you can eventually execute at the arcade/home versions? There isn't a training mode and the resolution and scroll speed are pretty low without any way to change it, and you can't even use the note color choice to improve readability, so it's kinda lame in that regard too. The combo counter also renders above the notes which makes reading even harder.

overall yea I commend them for trying but there really don't be much reason to play this. perhaps it would be fun to emulate to adjust controls to match a dance pad to get some 8-bit DDR and perhaps the sequels make it a better practice tool, but overall this first entry is just a novelty and nothing much else

My main problem here is the control scheme, but I can't really fault anything but the system that this is on for that. Due to the fact you can't push opposite cardinal directions on a D-pad plus the GBC only having 2 face buttons it do mean that A is right and B is up and u just gotta play it like that. They did make a finger-sized pad that can go over the GBC, bless their heart, but it still probably isn't the most optimal IMO. And yes, I was insane enough to try hooking this up to the gamecube game boy player to see if I could play it with a gamecube DDR pad. It unfortunately didn't work as the game still doesn't know how to detect both cardinal directions from the D-pad at the same time. Can't really fault them for that one ngl.

I guess the point of this is to practice the rhythmic patterns and maps for various DDR songs so that you can eventually execute at the arcade/home versions? There isn't a training mode and the resolution and scroll speed are pretty low without any way to change it, and you can't even use the note color choice to improve readability, so it's kinda lame in that regard too. The combo counter also renders above the notes which makes reading even harder.

overall yea I commend them for trying but there really don't be much reason to play this. perhaps it would be fun to emulate to adjust controls to match a dance pad to get some 8-bit DDR and perhaps the sequels make it a better practice tool, but overall this first entry is just a novelty and nothing much else

It feels mean to compare this to its predecessor but Virtue's Last Reward just doesn't have the sheer joy and thrill that Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors had. Its lore simultaneously wants to develop and exacerbate the insanity that 999 spent slowly unspooling, but it doesn't want to approach that level of multifaceted storytelling with nearly the same drama or heightened sense of panic. When I learned of a new element within the story, I didn't feel as strong of a sense of bewilderment or clairvoyance-level realization, but rather a sense of mild satisfaction. That's the thing that gets me about this game, I suppose: It works, but it doesn't tug at my emotions as much as 999 did. The chaos is ramped up but it just doesn't feel as urgent or interesting.

The character drama in particular is maybe my biggest gripe with the game overall. Every conversation is considerably longer and more quippy at the cost of information density, there's this sense of irreverence that feels extremely out of place. Of course, you could blame this on the advent of the Danganronpa franchise and its mockery in the face of certain death, but that series has its moments to refrain from indulging in its hypersexuality and humor in service of a bigger idea that climbs towards a hostile thriller screenplay. Additionally, the irreverence is used to help build onto the dread—were it not for Monokuma's complete and utter disregard for his subjects' lives, there'd be less panic among them.

The characters in VLR, on the other hand, are poised to joke and shove corny banter in nearly every conversation given enough time, such that it stands to kill a lot of the intensity that the holistic story builds. I would much rather a short, important conversation than a long one that stands to remove any given amount goodwill I have for the main characters. This lack of brevity is also not helped by the gargantuan amount of time that it takes between various novel segments, showcasing a very annoying dot moving across the map for every single possible migration of the characters. At a certain point in my playthrough, I started scheduling for these intermissions and texting friends over actually trying to remain immersed with a medium that ejected me from immersion to begin with.

That's not to say it's a bad game, far from it—once again in no small part to the thoughtful escape room design employed with a similar (but not exact same) grace as its predecessor. The increase in difficulty is something I rather appreciate, even if it comes at the cost of breaking immersion sometimes. I especially appreciate the safe system, though it has its drawbacks with certain room-end puzzles. The broader story itself, divorced from being attached to the game and the individual writing choices I dislike, is excellent scaffolding around the original lore that 999 set up. It's just a shame that this story had to shake out this way, because as a game it fails to excite me beyond its lore and individual chambers.

EDIT, 23-MARCH-2024:

My neglect to mention the very casual misogyny present in this game is starting to bug me greatly, so allow me to comment on the reality that Sigma and the rest of the characters either are victims or enablers of horrific womanizing. In a shocking departure from 999's relatively minute jokes about sexuality that are unimportant, minor facets of individual characters only appearing once or twice, Virtue's Last Reward takes the bold move to make Sigma a sexual harasser. In every possible route, he is poised to interact with at least one of the female characters with a variety of dehumanizing and, frankly, horrible sex pestery. He even remarks that Clover (who in VLR is small and skinny but an adult) is seemingly jailbait.

Misogynist characters are not inherently detrimental to a story if it is done with the tact and angling that it deserves. I hold the idea that depiction is not necessarily endorsement of the depicted. However, VLR's main character being an incessantly horny poon-hound who can be led to do just about anything with the promise of someone's panties getting stripped off is so irritating after 20 hours of playing the game that it ceases to be worthwhile as a facet of a character worth exploring. There is no benefit to it in this story.

The character drama in particular is maybe my biggest gripe with the game overall. Every conversation is considerably longer and more quippy at the cost of information density, there's this sense of irreverence that feels extremely out of place. Of course, you could blame this on the advent of the Danganronpa franchise and its mockery in the face of certain death, but that series has its moments to refrain from indulging in its hypersexuality and humor in service of a bigger idea that climbs towards a hostile thriller screenplay. Additionally, the irreverence is used to help build onto the dread—were it not for Monokuma's complete and utter disregard for his subjects' lives, there'd be less panic among them.

The characters in VLR, on the other hand, are poised to joke and shove corny banter in nearly every conversation given enough time, such that it stands to kill a lot of the intensity that the holistic story builds. I would much rather a short, important conversation than a long one that stands to remove any given amount goodwill I have for the main characters. This lack of brevity is also not helped by the gargantuan amount of time that it takes between various novel segments, showcasing a very annoying dot moving across the map for every single possible migration of the characters. At a certain point in my playthrough, I started scheduling for these intermissions and texting friends over actually trying to remain immersed with a medium that ejected me from immersion to begin with.

That's not to say it's a bad game, far from it—once again in no small part to the thoughtful escape room design employed with a similar (but not exact same) grace as its predecessor. The increase in difficulty is something I rather appreciate, even if it comes at the cost of breaking immersion sometimes. I especially appreciate the safe system, though it has its drawbacks with certain room-end puzzles. The broader story itself, divorced from being attached to the game and the individual writing choices I dislike, is excellent scaffolding around the original lore that 999 set up. It's just a shame that this story had to shake out this way, because as a game it fails to excite me beyond its lore and individual chambers.

EDIT, 23-MARCH-2024:

My neglect to mention the very casual misogyny present in this game is starting to bug me greatly, so allow me to comment on the reality that Sigma and the rest of the characters either are victims or enablers of horrific womanizing. In a shocking departure from 999's relatively minute jokes about sexuality that are unimportant, minor facets of individual characters only appearing once or twice, Virtue's Last Reward takes the bold move to make Sigma a sexual harasser. In every possible route, he is poised to interact with at least one of the female characters with a variety of dehumanizing and, frankly, horrible sex pestery. He even remarks that Clover (who in VLR is small and skinny but an adult) is seemingly jailbait.

Misogynist characters are not inherently detrimental to a story if it is done with the tact and angling that it deserves. I hold the idea that depiction is not necessarily endorsement of the depicted. However, VLR's main character being an incessantly horny poon-hound who can be led to do just about anything with the promise of someone's panties getting stripped off is so irritating after 20 hours of playing the game that it ceases to be worthwhile as a facet of a character worth exploring. There is no benefit to it in this story.

Musical Accompaniment

A multi-media experience so expansive and revolutionary it had to be put on TWO tapes.

In all seriousness though, I think most descriptions of this draw a weird line of comparison with trying to match it to one specific medium. You'll see the odd person say that this is an "interactive music video" or an "interactive movie" — I don't think either of those completely make this make sense.

Deus Ex Machina primarily consists of various scenes you can interact with set to an accompanying album which features vocal and musical accompaniment, loosely putting together a story reminiscent of the Shakespearean 'As You Like It'. The seven stages of a 'defect' in an allegorical science-fiction world woefully painted with the fantastical and broad strokes you would expect in British popular media, complete with theatrical music and story beats you'd expect from mainland Britain post-The Wall.

For the most part, you are a bystander without much agency towards the situation at hand, a single square bunch of pixels only goading other pixels to bounce off you or simply waiting idly by as a percentage meter ever so slowly drains from 100% until 0%. Perhaps a lump of molecules that sees existence as a recycled cell, interacting with new parts of the body. One moment a simple muscle cell in the neck so the newborn can let out its first roaring cry, the other a brain cell for coordinating jumps across barbed wire while connecting your physical efforts to political motivation.

In this sense, the protagonist of Deus Ex Machina is equal to most fleshed human. We are born, we live for a belief, we evolve it over time, and we die having moved and changed to the point of sheer unrecognizability. Even the traumatic probing and prodding by police and military commanders echo the lived experiences of minorities who never got to live a 'normal life', one unhampered by brutality. The only thing that truly changes is how we, the audience, view it. To us, we simply see numbers ticking down on a screen. To the protagonist, it is years gone by in an instant.

'Imagine if this were nothing but an electronic game. Your life is expressed as a percentage score. Observe the percentage. Your score changes.'

A multi-media experience so expansive and revolutionary it had to be put on TWO tapes.

In all seriousness though, I think most descriptions of this draw a weird line of comparison with trying to match it to one specific medium. You'll see the odd person say that this is an "interactive music video" or an "interactive movie" — I don't think either of those completely make this make sense.

Deus Ex Machina primarily consists of various scenes you can interact with set to an accompanying album which features vocal and musical accompaniment, loosely putting together a story reminiscent of the Shakespearean 'As You Like It'. The seven stages of a 'defect' in an allegorical science-fiction world woefully painted with the fantastical and broad strokes you would expect in British popular media, complete with theatrical music and story beats you'd expect from mainland Britain post-The Wall.

For the most part, you are a bystander without much agency towards the situation at hand, a single square bunch of pixels only goading other pixels to bounce off you or simply waiting idly by as a percentage meter ever so slowly drains from 100% until 0%. Perhaps a lump of molecules that sees existence as a recycled cell, interacting with new parts of the body. One moment a simple muscle cell in the neck so the newborn can let out its first roaring cry, the other a brain cell for coordinating jumps across barbed wire while connecting your physical efforts to political motivation.

In this sense, the protagonist of Deus Ex Machina is equal to most fleshed human. We are born, we live for a belief, we evolve it over time, and we die having moved and changed to the point of sheer unrecognizability. Even the traumatic probing and prodding by police and military commanders echo the lived experiences of minorities who never got to live a 'normal life', one unhampered by brutality. The only thing that truly changes is how we, the audience, view it. To us, we simply see numbers ticking down on a screen. To the protagonist, it is years gone by in an instant.

'Imagine if this were nothing but an electronic game. Your life is expressed as a percentage score. Observe the percentage. Your score changes.'

Super Mario 64

1996

Where's My Water?

2011

I picked this game because Tron was one of my main in the MVC games, and I got a surprising good time with it!

Close your eyes for a second and imagine a game completely based on the gimmicks of Pokemon's Team Rocket or Dorombo from Yatterman.

This is what is The Misadventures of Tron Bonne is: a cheesy spin off based on one of Megaman best side characters, with a silly premise, and tons of comedic dialoges and shenanigans.

This game offers a lot of different set of side-games and gameplay options, that adds a lot of charm to the title.

Though if I gotta be honest, not all of them are bangers.

The "story chapter" where you control Tron and her mechs are great and completely capture the charm of the Legends series. And the ability to befriend any of the Servbots, each with different stats and abilities, is really adorable. The Boss Battle are also really neat!

But.... some of the other sections can be too tedious: the cave explorations can become monotonous pretty soon, the puzzle cargo sections are an unnecessarily obligatory sections that breaks the rhythm of the game, the mission where you have to capture animals are nice but nothing special....

... and the game doesn't have enough Teisel, dang it! I want more Teisel, he is cool!

But yeah, this game is still reallly gìcharming! It may not fill the void for a Megaman Legends 3, but it is still worth checking out if you are a fan of the series.

Close your eyes for a second and imagine a game completely based on the gimmicks of Pokemon's Team Rocket or Dorombo from Yatterman.

This is what is The Misadventures of Tron Bonne is: a cheesy spin off based on one of Megaman best side characters, with a silly premise, and tons of comedic dialoges and shenanigans.

This game offers a lot of different set of side-games and gameplay options, that adds a lot of charm to the title.

Though if I gotta be honest, not all of them are bangers.

The "story chapter" where you control Tron and her mechs are great and completely capture the charm of the Legends series. And the ability to befriend any of the Servbots, each with different stats and abilities, is really adorable. The Boss Battle are also really neat!

But.... some of the other sections can be too tedious: the cave explorations can become monotonous pretty soon, the puzzle cargo sections are an unnecessarily obligatory sections that breaks the rhythm of the game, the mission where you have to capture animals are nice but nothing special....

... and the game doesn't have enough Teisel, dang it! I want more Teisel, he is cool!

But yeah, this game is still reallly gìcharming! It may not fill the void for a Megaman Legends 3, but it is still worth checking out if you are a fan of the series.

Victoria 3

2022

I asked for a whirling, living, breathing machine, and she gave me the hell I most desired.

Economics is kinda bullshit, okay? I’m a communist, plenty of you fuckers are communists, we’re obligated to believe that if nothing else. But wouldn’t it kinda be neat if economics had something to it, if everything was just supply and demand at various levels of scale, if you could feel the veins within the invisible hand of the market and twist them in any way you liked? Fundamentally, this is what Victoria 3 offers the player: You get to build an economy and make it run so goddamn good that you launch your country’s standard of living into the stratosphere.

The process of industrialization is the beating metal heart of this game. It starts, if you are a weak enough power, at the most basic level: You set up logging camps, use the wood you produce to build tools, use those tools in your logging camps to increase productivity, start mining iron with the tools you built, increase the efficiency of tools using that iron, and on and on it goes. It’s all very straightforward in a line by line description, but fails entirely to capture the dynamic energy that sets this apart from other grand strategy games like it. That energy comes from the populations. You’ll hear this come up whenever people discuss Victoria as a series: It’s all about population management. You want to meet their material needs, provide them with jobs, track what classes of society they come from and who you are empowering, so on and so forth. It’s all about the populations.

But there’s almost a sense that management is the wrong word entirely—left alone, your populations manage themselves. They’ll work on subsistence farms and provide their own needs, and everything will stay at a relatively good equilibrium unless a greater power swoops by and annexes your entire country out of the blue. Whoops! There’s a very real pressure to be better, be stronger, be more capable of resisting imperial powers, and this can only be managed with a directed vision. Pure reaction will never be enough. This is why resistance movements and rebellions in the real world do not merely dissolve once they have achieved their immediate goals—dissolution of the state creates a power vacuum that is just asking to be filled. (Vincent Bevins writes about this phenomena at length in relation to modern mass movements in his excellent new book If We Burn, as a side note. Please read it!)

No, management implies that you are creating from the ground up the forces of society. But these forces arise naturally—they are a structure inherent to any group of people interacting at scale, though they may manifest in different modes. Our role is not to create, but to direct as best we can the immense forces that we already possess. This is the feeling you have when your country begins to industrialize and you see the basic production you had at first start to swirl in self-powering feedback loops, profits seemingly arising from nowhere by the sheer nature of the movement of money between industry and consumer and government. There is no better feeling than when you painstakingly direct the production methods of each factory and construction company and mine, one by one transitioning to the new tools you have access to, causing your country’s productive capacity to explode exponentially, only ever growing bigger and bigger. Your standard of living increases, industrialists and the petite bourgeoisie grow more powerful, and demand more and more—

And so you become a monster, lost to pure momentum.

My favorite thing to do in this game is to play as marginalized and minor powers across the world. It’s incredibly satisfying to do that initial work of building something from nothing. With the way that this game encourages you to think about populations at all times, it almost feels tangible how many people you are pulling out of poverty. But with smaller nations, there’s always a ceiling. This takes one of two forms: resource shortages, or population shortages. The first of these is not such a big deal—this is what trade fundamentally solves. Sometimes you have way too much iron and need more oil. The solution presents itself. But population shortages? If you run into these, you’re fucked.

See, this machine of pure human and industrial momentum is always stealing just a little bit from the future. The process of industrialization is a challenge to outrun the consequences which you necessitate by engaging in industrialization. Your profits come from constant expansion and growth. Your citizens are happier when you are doing more, cutting down more trees, mining more iron, squeezing every last drop of steel out of the resources you have. But what if there is no expansion left in the interior? You can’t build any more factories, you don’t have people to work in them! In fact, given how much of your economy depends on the construction sector, you'll even start to implode, unable to sufficiently create demand for all the goods you've been producing, if you're unable to keep building. How can you continue to compete? If you don’t compete with the global market, they will overtake you, grow more powerful, be able to raise a greater army, and then you will be back where you started—just a minor power swept away by the colonizers and conquerers that surround you. What can you do when you don’t have any of your future left to steal from? You steal it from someone else.

This is the enticing trap of colonialism, for once your country tastes the labor, the goods, the blood of one colony, they will never be satisfied. Interest groups are often a mechanic that feels a little half-baked and oversimplified, but on this point they feel fundamentally correct: Basically no group within a colonial power opposes colonization. It’s just objectively profitable for them, when the world is filtered through this lens of economics to such an extent that all is consumed by it. Even when your society has more than anyone else in the world, they still desire to just consume more and more and more. I’d almost say this game is cynical if it wasn’t so fucking on point. When the world is all an abstract map of economic affairs, the desire to paint your color across the world is almost natural. For a moment, I understand how we got to where we are.

But then I zoom in on the world and it comes alive, and I can understand no longer.

- - -

A post-script as thanks for reading:

I find recently that most of my media analysis tends to find itself drawn magnetically to human nature as a concept in one way or another. Sometimes it's an obvious connection, like Killers of the Flower Moon, and sometimes it's a little more obtuse, as with this review. But even here we made the connection at the end: "the desire to paint your color across the world is almost natural." I think this actually comes full circle to the comment I made about economics being bullshit at the beginning of the review, a connection which I'll explore in a moment. I think it's probably a very important idea to focus on because it seems to deeply underpin basically all of how we understand the world, and I think we don't get to the center of that nearly often enough. How can you deconstruct an ideology without understanding its foundations?

There's this pretty fundamental assertion that every regressive, conservative, etc. etc. likes to make in their art, which is that on some level This Is Just How Things Are, which always takes the form of telling us that some particular tendency is just part of human nature. Isn't it just so convenient that those who did horrific evil in order to claw their way to the top of hegemony, and who continue to employ great violence at their behest in order to maintain that power, didn't really do anything bad because if everyone does something how can it really be bad? It's a deeply false but psychologically necessary claim: That the evil I do is not evil, and you would have done it too if you were me.

It's the same reduction that is made to turn humans into economic machines—understanding us simply as a set of material inputs and outputs who consume and produce things. It's a claim that if you had the same material conditions, you would necessarily do the same thing. But this denies the "you" in you, doesn't it? Think about yourself for a moment. Find where "you" are, the consciousness and the observer of the consciousness, whatever that means to you. How is this amorphous primal beast of a thing reducible to deterministic inputs and outputs? Do you really believe that? This is merely an assertion of their axioms of truth onto yours, a refusal to negotiate reality with you but instead an insistence of their own experience, a complete and utter denial of the real of the subjective, of the concept of a You! It is the ultimate solipsism, the greatest sin, the making of man into machine with a computerized brain, the ooze of capital left behind in the creases of everyone's brain from its utter hegemonic power in the ideological realm.

All of which is why I say that economics (or rather, the mainstream capitalist understanding of economics) is bullshit—it is a fundamental reduction of humans to being consumers and producers, and that can never meaningfully capture the picture of any social structure that emerges from how we interact with one another. You've gotta look elsewhere to understand that. It's stuck too deep in the realm of asserting its own axioms, that great circular reasoning, to hold any real truth. It's fundamentally inflexible and immobile in a way that the absolute reality of what we call a political economy can never be reduced to.

Victoria 3 captures all of this incredibly concretely, a little glimpse of the irreducibility behind economy, the first of the shapes in its stages of dialectical development on the way to understanding what that irreducibility even is. It's an astounding achievement, even if it is limited at times by the boundaries of its understanding and imagination.

Economics is kinda bullshit, okay? I’m a communist, plenty of you fuckers are communists, we’re obligated to believe that if nothing else. But wouldn’t it kinda be neat if economics had something to it, if everything was just supply and demand at various levels of scale, if you could feel the veins within the invisible hand of the market and twist them in any way you liked? Fundamentally, this is what Victoria 3 offers the player: You get to build an economy and make it run so goddamn good that you launch your country’s standard of living into the stratosphere.

The process of industrialization is the beating metal heart of this game. It starts, if you are a weak enough power, at the most basic level: You set up logging camps, use the wood you produce to build tools, use those tools in your logging camps to increase productivity, start mining iron with the tools you built, increase the efficiency of tools using that iron, and on and on it goes. It’s all very straightforward in a line by line description, but fails entirely to capture the dynamic energy that sets this apart from other grand strategy games like it. That energy comes from the populations. You’ll hear this come up whenever people discuss Victoria as a series: It’s all about population management. You want to meet their material needs, provide them with jobs, track what classes of society they come from and who you are empowering, so on and so forth. It’s all about the populations.

But there’s almost a sense that management is the wrong word entirely—left alone, your populations manage themselves. They’ll work on subsistence farms and provide their own needs, and everything will stay at a relatively good equilibrium unless a greater power swoops by and annexes your entire country out of the blue. Whoops! There’s a very real pressure to be better, be stronger, be more capable of resisting imperial powers, and this can only be managed with a directed vision. Pure reaction will never be enough. This is why resistance movements and rebellions in the real world do not merely dissolve once they have achieved their immediate goals—dissolution of the state creates a power vacuum that is just asking to be filled. (Vincent Bevins writes about this phenomena at length in relation to modern mass movements in his excellent new book If We Burn, as a side note. Please read it!)

No, management implies that you are creating from the ground up the forces of society. But these forces arise naturally—they are a structure inherent to any group of people interacting at scale, though they may manifest in different modes. Our role is not to create, but to direct as best we can the immense forces that we already possess. This is the feeling you have when your country begins to industrialize and you see the basic production you had at first start to swirl in self-powering feedback loops, profits seemingly arising from nowhere by the sheer nature of the movement of money between industry and consumer and government. There is no better feeling than when you painstakingly direct the production methods of each factory and construction company and mine, one by one transitioning to the new tools you have access to, causing your country’s productive capacity to explode exponentially, only ever growing bigger and bigger. Your standard of living increases, industrialists and the petite bourgeoisie grow more powerful, and demand more and more—

And so you become a monster, lost to pure momentum.

My favorite thing to do in this game is to play as marginalized and minor powers across the world. It’s incredibly satisfying to do that initial work of building something from nothing. With the way that this game encourages you to think about populations at all times, it almost feels tangible how many people you are pulling out of poverty. But with smaller nations, there’s always a ceiling. This takes one of two forms: resource shortages, or population shortages. The first of these is not such a big deal—this is what trade fundamentally solves. Sometimes you have way too much iron and need more oil. The solution presents itself. But population shortages? If you run into these, you’re fucked.

See, this machine of pure human and industrial momentum is always stealing just a little bit from the future. The process of industrialization is a challenge to outrun the consequences which you necessitate by engaging in industrialization. Your profits come from constant expansion and growth. Your citizens are happier when you are doing more, cutting down more trees, mining more iron, squeezing every last drop of steel out of the resources you have. But what if there is no expansion left in the interior? You can’t build any more factories, you don’t have people to work in them! In fact, given how much of your economy depends on the construction sector, you'll even start to implode, unable to sufficiently create demand for all the goods you've been producing, if you're unable to keep building. How can you continue to compete? If you don’t compete with the global market, they will overtake you, grow more powerful, be able to raise a greater army, and then you will be back where you started—just a minor power swept away by the colonizers and conquerers that surround you. What can you do when you don’t have any of your future left to steal from? You steal it from someone else.

This is the enticing trap of colonialism, for once your country tastes the labor, the goods, the blood of one colony, they will never be satisfied. Interest groups are often a mechanic that feels a little half-baked and oversimplified, but on this point they feel fundamentally correct: Basically no group within a colonial power opposes colonization. It’s just objectively profitable for them, when the world is filtered through this lens of economics to such an extent that all is consumed by it. Even when your society has more than anyone else in the world, they still desire to just consume more and more and more. I’d almost say this game is cynical if it wasn’t so fucking on point. When the world is all an abstract map of economic affairs, the desire to paint your color across the world is almost natural. For a moment, I understand how we got to where we are.

But then I zoom in on the world and it comes alive, and I can understand no longer.

- - -

A post-script as thanks for reading:

I find recently that most of my media analysis tends to find itself drawn magnetically to human nature as a concept in one way or another. Sometimes it's an obvious connection, like Killers of the Flower Moon, and sometimes it's a little more obtuse, as with this review. But even here we made the connection at the end: "the desire to paint your color across the world is almost natural." I think this actually comes full circle to the comment I made about economics being bullshit at the beginning of the review, a connection which I'll explore in a moment. I think it's probably a very important idea to focus on because it seems to deeply underpin basically all of how we understand the world, and I think we don't get to the center of that nearly often enough. How can you deconstruct an ideology without understanding its foundations?

There's this pretty fundamental assertion that every regressive, conservative, etc. etc. likes to make in their art, which is that on some level This Is Just How Things Are, which always takes the form of telling us that some particular tendency is just part of human nature. Isn't it just so convenient that those who did horrific evil in order to claw their way to the top of hegemony, and who continue to employ great violence at their behest in order to maintain that power, didn't really do anything bad because if everyone does something how can it really be bad? It's a deeply false but psychologically necessary claim: That the evil I do is not evil, and you would have done it too if you were me.

It's the same reduction that is made to turn humans into economic machines—understanding us simply as a set of material inputs and outputs who consume and produce things. It's a claim that if you had the same material conditions, you would necessarily do the same thing. But this denies the "you" in you, doesn't it? Think about yourself for a moment. Find where "you" are, the consciousness and the observer of the consciousness, whatever that means to you. How is this amorphous primal beast of a thing reducible to deterministic inputs and outputs? Do you really believe that? This is merely an assertion of their axioms of truth onto yours, a refusal to negotiate reality with you but instead an insistence of their own experience, a complete and utter denial of the real of the subjective, of the concept of a You! It is the ultimate solipsism, the greatest sin, the making of man into machine with a computerized brain, the ooze of capital left behind in the creases of everyone's brain from its utter hegemonic power in the ideological realm.

All of which is why I say that economics (or rather, the mainstream capitalist understanding of economics) is bullshit—it is a fundamental reduction of humans to being consumers and producers, and that can never meaningfully capture the picture of any social structure that emerges from how we interact with one another. You've gotta look elsewhere to understand that. It's stuck too deep in the realm of asserting its own axioms, that great circular reasoning, to hold any real truth. It's fundamentally inflexible and immobile in a way that the absolute reality of what we call a political economy can never be reduced to.

Victoria 3 captures all of this incredibly concretely, a little glimpse of the irreducibility behind economy, the first of the shapes in its stages of dialectical development on the way to understanding what that irreducibility even is. It's an astounding achievement, even if it is limited at times by the boundaries of its understanding and imagination.

weirdly the complete antithesis of what mcgee was going for in the sequel,, the sequel is bright and colorful but ultimately dour and overly dark in tone and story. this is one of the most dark looking games ive ever played and the map layouts for each level are so utterly confounding and disorienting, a labyrinthine hell constructed by others specifically for u to suffer during. the first is a game about growth and progression, forgiveness and regret and the pain that comes w both, the sequel is concerned w regression and ig I just don’t vibe w that as much. this belongs more to an era of game design like max payne or rule of rose where ur small and the world is big and there’s plenty of ppl who don’t want you to exist within it. the structure of every world is chaotic and dizzying and scary! I love some of the weirdo imagery the enemies can conjure up like the flying bomb dropping bugs that seem almost military like.

there’s so much being said here even w like v minimal actual words being said,, alice herself conveys sm through grunts and screams it’s actually kind of wild. a simple jump to a ledge sounds blood cur-tingling and filled w anger + desperation. idk to see her suffer so often and in such extreme ways and come out the other side (at least for this game) a better and more whole person is rlly fucking fulfilling and satisfying to experience.

part of me wishes there was a third game and a better ending to both alice the character and the series, but also I realize that this series obv took a lot out of mcgee and was coming from a place that’s maybe better left sitting dormant for his own mental health. he seems kind of happy as a retired old guy living in shanghai that’s left behind a wealth of art that means a lot to a lot of ppl and now just makes emo plushes that while don’t mean rlly anything to me obv mean something to enough ppl. I think that’s nice ^_^

there’s so much being said here even w like v minimal actual words being said,, alice herself conveys sm through grunts and screams it’s actually kind of wild. a simple jump to a ledge sounds blood cur-tingling and filled w anger + desperation. idk to see her suffer so often and in such extreme ways and come out the other side (at least for this game) a better and more whole person is rlly fucking fulfilling and satisfying to experience.

part of me wishes there was a third game and a better ending to both alice the character and the series, but also I realize that this series obv took a lot out of mcgee and was coming from a place that’s maybe better left sitting dormant for his own mental health. he seems kind of happy as a retired old guy living in shanghai that’s left behind a wealth of art that means a lot to a lot of ppl and now just makes emo plushes that while don’t mean rlly anything to me obv mean something to enough ppl. I think that’s nice ^_^

Not bad so much as deeply boring. Little to no challenge, stiff platforming, a power-up that in many ways reduces your performance. I finished it for a challenge, and I don't regret it, but with titles like these populating the industry's early Holiday titles, I can see why we moved away from games focused on the season.

If you're insistent to play it, play the Mega Drive version, as the SNES version has some inescapable locations you can end up in on accident.

If you're insistent to play it, play the Mega Drive version, as the SNES version has some inescapable locations you can end up in on accident.

Bomb Bee

1979

A͍̭̒̔̇̑̉D͚̩̫̙̰̭́ͯ͋̅̄͑͐́V̧̡̮̱ͤͯǍ̴͓̬͙̮̥͙̕N̵̖̖̅̈̆ͯ̈̉͐C̸͙̖̱͖̟̮̜̜͊̈̌ͭ̀͑͛͝ͅĖ͕̙͈͆̆̈̊̽ͮͫ̚D̷̹ͮ́ͣ͛̅ ̷̨̝̮̩̖͔̱͈͊͆ͦ͛ͅP̷̣̹̱̰̭̿̊ͫͧ͂̀Ỉ̧̜͔ͭ̃ͨͩ̋́̅͋ͅN͖̱̜ͧͯ̀̐B̮̤̩͖͕̙̪ͭ̋͒̈́̇ͧ̌̾ͤͅÁ̷̫̗̬ͭ̂͝ͅL͉͕͙͕͕ͤ̇ͭ͂̑ͬL͍̹̽̃ͮ̅̈̃͌ ̣̯̣͉̺ͪ͊̂̑ͫͫ͗S̡͕͖̗͎̼ͨI̡̛̫̰̝͖̙̝̤͗ͬ́̏̉͗ͅM̠̖̋̉̅̽̿ͧ̅̓͘U̶̷̝͙ͬͨ͒ͧ̐ͥ̀Ľ̸̟͓͎͈̈́͂ͭ̃ͪ̓͟A̯͇͕͎͙̻̿̂̒͒͐͛̇T̵̓̈́ͧ̍̓͏̞̮Ȏ̸̲̩̝͑̊̅̆̏R̥̤̤̰̜͇̩̬ͯ̈̆ͬ̄ͭ

Phoenix

1980

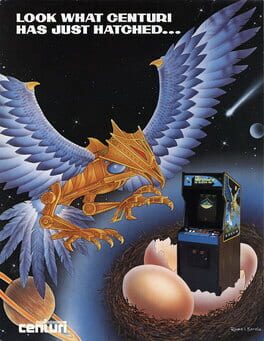

As the player ship blasts at the flying beetle enemy starfighters, they jet boost away with sparks popping behind them, snapping around the deep blue stars of the galaxy. An enemy ship collides with the player ship and with a bright yellow cloud of explosions as the ships shatter to pieces. When the player respawns and defeats all of the enemies, a strange series of orbs fly down in a wobbly wave pattern and eventually hatch into matte blue birds more than triple the size of my player ship, each with a ghoulish grin. Somehow, the player ship survives and flies through only to find a great mothership so big that it fills almost all visible space.

I am frightened.

I am frightened.

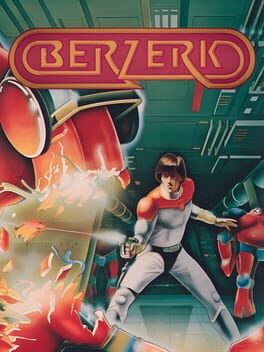

Berzerk

1980

"Chicken, fight like a robot!" blares the cabinet speaker as I generously leave some killbots alive, moving on to the next room. There's no end to them: monochrome sentinels of death, all bunching up along the walls, all waiting to fire. I ready the ray-gun and trudge forward, fingers on the trigger, reflected through the joystick. This continues for untold iterations as the numbers go up, the Evil Otto bounces down upon its hapless allies, and the rhythm of combat multiplies. Everyone has their place here, the guards uncaring for their neighbors and the smiley-faced custodian uniquely aware of this realm's absurdity.

Ok, ok, it's Berzerk, and it's not that complex aside from catalyzing the deaths of two hapless players. Compared to both emerging maze games and shooters like Space Invaders, this one's appeal must have been immediate: unpredictable gunfights, a sassy robotic narrator, and more chaos than something as scandalous as Death Race could have imagined. The origins of the run 'n gun style arguably trace back farther to Tank and its clones, but changing out vehicles for humanoid avatars lets the pacing slacken and rev up more granularly. Crashing into electrified walls becomes more of a threat than colliding with far-off aggressors, who now threaten more with split-second lasers than an opposite player careening into you. So the dynamic's similar but different enough from the motion-full Asteroids, with danger coming from less angles but requiring quicker reactions.

What undoubtedly helped Berzerk survive its encounter with Williams' Defender is the touted "sense of humor" seen with Evil Otto and how it affects players and AI alike. After all, why risk visiting the next dungeon screen and quickly dying when one could just stay put, safe and sound? The danger and necessary push of Evil Otto remains one of the golden age's most iconic symbols, both scary and ironic. And it only gets better when a savvy player sicks the boisterous bounding ball on unsuspecting droids, racking up points while kiting Otto around each arena. Counting score by each enemy's death, rather than players' successful shots, was maybe the smartest move to extend the game's longevity. There's an upper human limit of how long someone's going to traverse one nondescript room after another, but surviving long enough to abuse this scoring mechanic? Why the hell not!

I'd much rather try and master Jarvis' side-scrolling shooter if I'm having to choose between these games (that, and Defender technically started location testing and initial distribution at the start of '81). But there's a simple charm to creator Alan McNeil's attempt at crossing genre lines, evoking the first dungeon crawlers without their labored pace of play. McNeil himself came up with Berzerk's premise based on his own nightmare of robots chasing him through hallways, let alone the memory of security browbeater David Otto haunting the designer from his time working with Dave Nutting Associates. [1] People always talk about how this game feels like wandering through a dreamscape they can't escape, and I think there's some truth to that. On the bright side, it's cool to see McNeil take the early micro-processor lessons learned with Midway's Gun Fight (a recreation of Taito's TTL-chip classic Western Gun). We're talking about the guy who later laid the foundation of Macromedia Director and other technology, so it's unsurprising he could get so much from basic hardware.

Juking bots with Otto and luring them into fences calls an earlier game to mind: CHASE, a derivation of a 1976 BASIC game where players have to crash pursuers into objects and each other [2]. This puts Berzerk in the same conversation as other PC-to-arcade transitional software; in fact, it's one of the earliest examples. It's fascinating how much Stern's 1980 smash success treads the line between hobbyist sleeper hit and a throwback to much earlier media like the Berserker novels and publications like Creative Computing. From here, the tendrils extend towards Robotron and its ilk, let alone a direct sequel in Frenzy. I may be moving on from this weird and seemingly simple curiosity, yet it's going to reappear in one form or another as the '80s arcade era marches on.

Bibliography

[1] Hunter, William. “Berzerk.” The Dot Eaters (blog). Accessed January 1, 2024. <https://thedoteaters.com/?bitstory=bitstory-article-2/berzerk>

[2] David, Ahl, and Cotter Bill. “Chase (High Voltage Maze) - Cotter.” Creative Computing, January 1976. Accessed via Internet Archive. <http://archive.org/details/Creative_Computing_v02n01_Jan-Feb1976> Retrieved on January 6, 2024.

Ok, ok, it's Berzerk, and it's not that complex aside from catalyzing the deaths of two hapless players. Compared to both emerging maze games and shooters like Space Invaders, this one's appeal must have been immediate: unpredictable gunfights, a sassy robotic narrator, and more chaos than something as scandalous as Death Race could have imagined. The origins of the run 'n gun style arguably trace back farther to Tank and its clones, but changing out vehicles for humanoid avatars lets the pacing slacken and rev up more granularly. Crashing into electrified walls becomes more of a threat than colliding with far-off aggressors, who now threaten more with split-second lasers than an opposite player careening into you. So the dynamic's similar but different enough from the motion-full Asteroids, with danger coming from less angles but requiring quicker reactions.

What undoubtedly helped Berzerk survive its encounter with Williams' Defender is the touted "sense of humor" seen with Evil Otto and how it affects players and AI alike. After all, why risk visiting the next dungeon screen and quickly dying when one could just stay put, safe and sound? The danger and necessary push of Evil Otto remains one of the golden age's most iconic symbols, both scary and ironic. And it only gets better when a savvy player sicks the boisterous bounding ball on unsuspecting droids, racking up points while kiting Otto around each arena. Counting score by each enemy's death, rather than players' successful shots, was maybe the smartest move to extend the game's longevity. There's an upper human limit of how long someone's going to traverse one nondescript room after another, but surviving long enough to abuse this scoring mechanic? Why the hell not!

I'd much rather try and master Jarvis' side-scrolling shooter if I'm having to choose between these games (that, and Defender technically started location testing and initial distribution at the start of '81). But there's a simple charm to creator Alan McNeil's attempt at crossing genre lines, evoking the first dungeon crawlers without their labored pace of play. McNeil himself came up with Berzerk's premise based on his own nightmare of robots chasing him through hallways, let alone the memory of security browbeater David Otto haunting the designer from his time working with Dave Nutting Associates. [1] People always talk about how this game feels like wandering through a dreamscape they can't escape, and I think there's some truth to that. On the bright side, it's cool to see McNeil take the early micro-processor lessons learned with Midway's Gun Fight (a recreation of Taito's TTL-chip classic Western Gun). We're talking about the guy who later laid the foundation of Macromedia Director and other technology, so it's unsurprising he could get so much from basic hardware.

Juking bots with Otto and luring them into fences calls an earlier game to mind: CHASE, a derivation of a 1976 BASIC game where players have to crash pursuers into objects and each other [2]. This puts Berzerk in the same conversation as other PC-to-arcade transitional software; in fact, it's one of the earliest examples. It's fascinating how much Stern's 1980 smash success treads the line between hobbyist sleeper hit and a throwback to much earlier media like the Berserker novels and publications like Creative Computing. From here, the tendrils extend towards Robotron and its ilk, let alone a direct sequel in Frenzy. I may be moving on from this weird and seemingly simple curiosity, yet it's going to reappear in one form or another as the '80s arcade era marches on.

Bibliography

[1] Hunter, William. “Berzerk.” The Dot Eaters (blog). Accessed January 1, 2024. <https://thedoteaters.com/?bitstory=bitstory-article-2/berzerk>

[2] David, Ahl, and Cotter Bill. “Chase (High Voltage Maze) - Cotter.” Creative Computing, January 1976. Accessed via Internet Archive. <http://archive.org/details/Creative_Computing_v02n01_Jan-Feb1976> Retrieved on January 6, 2024.