Cold_Comfort

394 Reviews liked by Cold_Comfort

Star Fox

1993

It's a shame, isn't it?

These days, we have it all. We can easily access an entire console's library with a mere flick of our fingers through means that don't hurt anyone. You could play mods, fixes, hacks and all sorts of things to improve or build upon whatever it is you're interested in. We have everything we could imagine to play anything in gaming history, but despite all this, you can never stop time's continuous march forward. We grow older, we develop more as a society, and technology progresses towards it's next plateau until the next big breakthrough, but could you really know what it's like to play something from it's time period without knowledge of what we have now? To envision yourself as that five year old kid playing it for the very first time? Could you really?

The very first 3D game that I remember playing was Hard Drivin' on the Sega Genesis. It was an impressive looking racer for it's time, but even when I was that young and so full of imagination I only ever saw it as "neat". It wasn't exactly leaving a mark on me anytime soon with it's scenic barnyard aesthetic and lack of music during gameplay. It was funny to crash, that was about it. I laughed, and I went back to playing my 2D games of which many even today still enjoy. Three Dee? What of it? Star Fox you say? Super FX you say? I don't know what those are, but it sure sounds cool!

For me, it was something I couldn't believe. The immediate introduction with that cinematic shot of the giant carrier slowly approaching Corneria with the backing of that powerful and sinister orchestra hooked me immediately. I was amazed. Am I really playing this? Yes, yes I was. Soon as I knew it, I was piloting an Arwing and living that cinematic space-flying adventure with the coolest rock tune to grace my ears at the time. I was navigating through asteroid fields, taking part in chaotic assaults on Andross' space armada and destroying gigantic battleships from the inside in my own little trench run. This wasn't any old game I was used to, it was an experience, and it was amazing. I loved it, and I would never forget it.

...and now, all those... moments are lost on those who come after me, and I find myself alone and lonely on this mountaintop. Star Fox... was no longer considered that amazing, it was just..."neat", like Hard Drivin' on the Genesis. Heartbreaking. Some could be ignorant, some could be respectful, and others could even enjoy it, but I know that deep down they could never be awestruck by it. Their experience will never be the same as mine was, and it will never hit the same again. It's pathetic maybe to lament, but I've come to face the music. I will never meet someone from generations onward who will love this as much as me, and my loneliness will continue as I feel more and more like the last of my kind. Maybe it hit at just the right age as my creativity was just beginning to manifest? I dunno how else to describe my attachment. It rules, and it still has the best sound I have ever experienced off the system. Feel those enemy shots go past you as you boost through space, experience the explosions radiating off the bosses after they're defeated. God.....it's so good.

At the end of it all, Star Fox is still Star Fox and my heart never changed. If I must be alone on this mountain until I die, then so be it. I ain't moving.

These days, we have it all. We can easily access an entire console's library with a mere flick of our fingers through means that don't hurt anyone. You could play mods, fixes, hacks and all sorts of things to improve or build upon whatever it is you're interested in. We have everything we could imagine to play anything in gaming history, but despite all this, you can never stop time's continuous march forward. We grow older, we develop more as a society, and technology progresses towards it's next plateau until the next big breakthrough, but could you really know what it's like to play something from it's time period without knowledge of what we have now? To envision yourself as that five year old kid playing it for the very first time? Could you really?

The very first 3D game that I remember playing was Hard Drivin' on the Sega Genesis. It was an impressive looking racer for it's time, but even when I was that young and so full of imagination I only ever saw it as "neat". It wasn't exactly leaving a mark on me anytime soon with it's scenic barnyard aesthetic and lack of music during gameplay. It was funny to crash, that was about it. I laughed, and I went back to playing my 2D games of which many even today still enjoy. Three Dee? What of it? Star Fox you say? Super FX you say? I don't know what those are, but it sure sounds cool!

For me, it was something I couldn't believe. The immediate introduction with that cinematic shot of the giant carrier slowly approaching Corneria with the backing of that powerful and sinister orchestra hooked me immediately. I was amazed. Am I really playing this? Yes, yes I was. Soon as I knew it, I was piloting an Arwing and living that cinematic space-flying adventure with the coolest rock tune to grace my ears at the time. I was navigating through asteroid fields, taking part in chaotic assaults on Andross' space armada and destroying gigantic battleships from the inside in my own little trench run. This wasn't any old game I was used to, it was an experience, and it was amazing. I loved it, and I would never forget it.

...and now, all those... moments are lost on those who come after me, and I find myself alone and lonely on this mountaintop. Star Fox... was no longer considered that amazing, it was just..."neat", like Hard Drivin' on the Genesis. Heartbreaking. Some could be ignorant, some could be respectful, and others could even enjoy it, but I know that deep down they could never be awestruck by it. Their experience will never be the same as mine was, and it will never hit the same again. It's pathetic maybe to lament, but I've come to face the music. I will never meet someone from generations onward who will love this as much as me, and my loneliness will continue as I feel more and more like the last of my kind. Maybe it hit at just the right age as my creativity was just beginning to manifest? I dunno how else to describe my attachment. It rules, and it still has the best sound I have ever experienced off the system. Feel those enemy shots go past you as you boost through space, experience the explosions radiating off the bosses after they're defeated. God.....it's so good.

At the end of it all, Star Fox is still Star Fox and my heart never changed. If I must be alone on this mountain until I die, then so be it. I ain't moving.

With my teeth cut on the herculean likes of Castlevania: The Adventure and Geograph Seal, and without any deep-seated adoration for Super Mario Bros. it must come as little surprise I not only liked Super Mario Bros. Special, but outright loved it by the end. On a technical, graphical, audio, mechanical, and ludological level, SMBS is a whisper of a shadow of the Nintendo original. Despite the odds being stacked astronomically against them, however, the team at Hudson crafted something that becomes an earnest marvel. SMBS effectively parcels out the essence of SMB in single-screen microdoses of platforming not too dissimilar to Prince of Persia, N++, or Dizzy.

This limitation informed decision would fail utterly with the mechanics and physics of SMB, but SMBS' tweaks accommodate this well. With the exception of multi-screen jumps, each segment can stand on its own as a mini-level effectively disconnected from those surrounding it. In theory, this would be jarring and discordant. In practice, those self-contained bits and bobs ensure each challenge is approached from common ground under the assumption that the player might have zero momentum at the start. Both cautious and bold players benefit from this, the former is not punished for slowing down, the latter barely hindered by the transition between screens. With the peculiarities of the physics and controls, this seems outright necessary. Mario jumps like he's taking inspiration from Simon Belmont, his running stops if too many keyboard keys are pressed (ie. two), he has the inertia of a semi-truck loaded with tungsten. Getting a grip on this bizarro setup is an agony in itself, but a rewarding one when enormous chasms are eventually crossed without hesitation.

Also due to limitations is the inconsistent game speed. Playing at the default 4MHz clock speed of the Sharp X1, everything drips like pitch if Mario is Super and too many sprites are on screen (ie. two). If Mario is Small or absent from the screen, everything is entirely too fast, even by the standards of SMB. This drunken sway between two extremes is uncomfortable to listen too and uneven to play. However, it unintentionally presents the player a variety of ways with which to engage with the game. Should the player go Super or Fiery, the experience is slower but perhaps intended. Clearing enemies and obstacles makes the screens accelerate near their ends. If the player goes Super or Fiery and ensures they keep as many sprites on screen at once, the game slows further to allow greater precision in platforming on that screen. The safety net of not being Small Mario makes these two options the most lackadaisical. On the other hand, Small Mario makes the game run, if not fast, at least at a consistently higher speed. Jumps thereby become tighter, and Mario much more vulnerable. Clearing enemies and obstacles makes the screens accelerate near their ends, so a bold player can take their chances and double down on them to proceed as quickly as possible. On paper this is perhaps a meaningless choice, but in practice there arises a genuine balancing act of choosing whether or not to bother with power-ups, with clearing enemies, with going fast. By the end of my playthrough, I consistently stayed as Small Mario and threw caution to the wind, making for a tense but rewarding experience.

The (re-)introduction of enemies from Donkey Kong and Mario Bros. are icing on an absurd cake, their inclusion an anachronistic anomaly that presents just enough of a shift in player approach to be meaningful. Sidesteppers may serve an identical purpose to Spinies, but Fighterflies' hops, barrels' rolling, fireballs' outright immunity, and the imminent hazard of icicles all carve out niches of their own without being out of place.

Separately, every facet of Super Mario Bros. Special fails to cut the mustard. As a synthesis, it is remarkable. My victory genuinely felt like it had been hard won from some overwhelming force. The Geiger–Müller counter buzzing was a constant companion I grew fond of. The words of Princess Peach rang clear and true: "You cleared every world. You are the greatest player. Congraturations!" [sic]

I would never recommend anyone play Super Mario Bros. Special without the most open of minds, and even then I think most will get their fill by the time they clear World 1. Maybe I'm too sick in the head to interpret this as a 'bad' game. Maybe I'm to sick to see it as anything but amazing. Either way, its eight worlds sought to chew me up and spit me out. Instead, I prevailed.

This is not a Super Mario Bros. Special as the actual name suggests. The title screen and box make the true meaning subtly known. This is a Super Special Mario Bros. game.

This limitation informed decision would fail utterly with the mechanics and physics of SMB, but SMBS' tweaks accommodate this well. With the exception of multi-screen jumps, each segment can stand on its own as a mini-level effectively disconnected from those surrounding it. In theory, this would be jarring and discordant. In practice, those self-contained bits and bobs ensure each challenge is approached from common ground under the assumption that the player might have zero momentum at the start. Both cautious and bold players benefit from this, the former is not punished for slowing down, the latter barely hindered by the transition between screens. With the peculiarities of the physics and controls, this seems outright necessary. Mario jumps like he's taking inspiration from Simon Belmont, his running stops if too many keyboard keys are pressed (ie. two), he has the inertia of a semi-truck loaded with tungsten. Getting a grip on this bizarro setup is an agony in itself, but a rewarding one when enormous chasms are eventually crossed without hesitation.

Also due to limitations is the inconsistent game speed. Playing at the default 4MHz clock speed of the Sharp X1, everything drips like pitch if Mario is Super and too many sprites are on screen (ie. two). If Mario is Small or absent from the screen, everything is entirely too fast, even by the standards of SMB. This drunken sway between two extremes is uncomfortable to listen too and uneven to play. However, it unintentionally presents the player a variety of ways with which to engage with the game. Should the player go Super or Fiery, the experience is slower but perhaps intended. Clearing enemies and obstacles makes the screens accelerate near their ends. If the player goes Super or Fiery and ensures they keep as many sprites on screen at once, the game slows further to allow greater precision in platforming on that screen. The safety net of not being Small Mario makes these two options the most lackadaisical. On the other hand, Small Mario makes the game run, if not fast, at least at a consistently higher speed. Jumps thereby become tighter, and Mario much more vulnerable. Clearing enemies and obstacles makes the screens accelerate near their ends, so a bold player can take their chances and double down on them to proceed as quickly as possible. On paper this is perhaps a meaningless choice, but in practice there arises a genuine balancing act of choosing whether or not to bother with power-ups, with clearing enemies, with going fast. By the end of my playthrough, I consistently stayed as Small Mario and threw caution to the wind, making for a tense but rewarding experience.

The (re-)introduction of enemies from Donkey Kong and Mario Bros. are icing on an absurd cake, their inclusion an anachronistic anomaly that presents just enough of a shift in player approach to be meaningful. Sidesteppers may serve an identical purpose to Spinies, but Fighterflies' hops, barrels' rolling, fireballs' outright immunity, and the imminent hazard of icicles all carve out niches of their own without being out of place.

Separately, every facet of Super Mario Bros. Special fails to cut the mustard. As a synthesis, it is remarkable. My victory genuinely felt like it had been hard won from some overwhelming force. The Geiger–Müller counter buzzing was a constant companion I grew fond of. The words of Princess Peach rang clear and true: "You cleared every world. You are the greatest player. Congraturations!" [sic]

I would never recommend anyone play Super Mario Bros. Special without the most open of minds, and even then I think most will get their fill by the time they clear World 1. Maybe I'm too sick in the head to interpret this as a 'bad' game. Maybe I'm to sick to see it as anything but amazing. Either way, its eight worlds sought to chew me up and spit me out. Instead, I prevailed.

This is not a Super Mario Bros. Special as the actual name suggests. The title screen and box make the true meaning subtly known. This is a Super Special Mario Bros. game.

I have this propensity to never play games a second time, even the ones I love. It serves me well more often than not, because I greatly value backlog exploration and sheer variety over mechanical or scholarly mastery of any specific title. Where it bites me in the wahooey, however, is in largely skill-oriented titles like character action games, ones that demand keen attentiveness and willingness to retain and juggle knowledge of systems macro and micro. For as much as I love these games for their absolutely unbridled pomp and the hot-blooded verve that courses thru em - I know I’m not going to get the most out of them, I just don’t have that kind of attention. Bayonetta 1 is astoundingly good, but it’s a game I essentially Bronze Trophied my way through, and only watched .webms of people going sicko online for. I only knew what dodge offset WAS when I hit the last level, when it was too late for me 😔.

Bayorigins: Wily Beast and Weakest Creature is just a nice little scrimblo that forces a more steady pace with its longer runtime and focus on action adventure & metroidvania-lite elements. There is a more sensical focus on the storytelling here than in the mainline entries, exemplified through its presentation style of a children’s picturebook narrated by a granny. It’s all just nice, the visual direction is utterly astounding, and is the most blown away I’ve been by sheer artistry in a videogame in a very long time, the shader programmers were spinning in their chairs like the tasmanian devil on this one. With the combat being a touch more of a tertiary focus on the title than the rest, it allows itself time to slowly blossom through the course of the runtime with a steadily increasing amount of abilities, roadblocks and enemy gimmicks - and while there are no post-battle ranking screens to have Stone trophies nip at my heels, it felt immensely satisfying to sense myself mastering it under a more forgiving piecemeal delivery. It’s actually a little impressive how intuitive this control scheme becomes after an awkward starting period; forcing the player to control two separate characters by splitting the controller inputs down the middle. With its smart application within certain story beats, I became more than sold on the way this plays, kinda love it. For all these reasons, it's my favourite Bayonetta game. This is the warmest I’ve felt for a Platinum title since Wonderful 101, and while it doesn’t reach the same heights, it’s a miraculously good little spinoff to patch over my confidence in the studio that Bayo3 had dented.

Bayorigins: Wily Beast and Weakest Creature is just a nice little scrimblo that forces a more steady pace with its longer runtime and focus on action adventure & metroidvania-lite elements. There is a more sensical focus on the storytelling here than in the mainline entries, exemplified through its presentation style of a children’s picturebook narrated by a granny. It’s all just nice, the visual direction is utterly astounding, and is the most blown away I’ve been by sheer artistry in a videogame in a very long time, the shader programmers were spinning in their chairs like the tasmanian devil on this one. With the combat being a touch more of a tertiary focus on the title than the rest, it allows itself time to slowly blossom through the course of the runtime with a steadily increasing amount of abilities, roadblocks and enemy gimmicks - and while there are no post-battle ranking screens to have Stone trophies nip at my heels, it felt immensely satisfying to sense myself mastering it under a more forgiving piecemeal delivery. It’s actually a little impressive how intuitive this control scheme becomes after an awkward starting period; forcing the player to control two separate characters by splitting the controller inputs down the middle. With its smart application within certain story beats, I became more than sold on the way this plays, kinda love it. For all these reasons, it's my favourite Bayonetta game. This is the warmest I’ve felt for a Platinum title since Wonderful 101, and while it doesn’t reach the same heights, it’s a miraculously good little spinoff to patch over my confidence in the studio that Bayo3 had dented.

This game, recently rereleased as "River City Girls Zero", is a passable beatemup I suppose, but it's a bit dry as far as gameplay goes and it's quite overlong. I liked that you could switch between four characters for a chunk of the game, but they don't really differ much in playstyle and so it's more like having four health bars. They decide to cut you back down to just two in the home stretch, though, which was annoying. Also annoying was the lack of health bars on enemies and even bosses, though I hear that is pretty common throughout the Kunio-kun games.

Though I much prefer the off-beat personality showcased here over River City Girls' internet poisoned dialogue and frustrating cameos, it's not much of a better game in other regards either. I guess I'm just not as hard on it because the latter was like only four years ago and by then it should just be well known how to not make a shitty beatemup if you're going to make one to begin with. I still can't really get over how disappointing that one was. Fucking WayForward. I hope they burn.

Though I much prefer the off-beat personality showcased here over River City Girls' internet poisoned dialogue and frustrating cameos, it's not much of a better game in other regards either. I guess I'm just not as hard on it because the latter was like only four years ago and by then it should just be well known how to not make a shitty beatemup if you're going to make one to begin with. I still can't really get over how disappointing that one was. Fucking WayForward. I hope they burn.

Final Fantasy X-2

2003

Yuna: "My two girlfriends. And yes, they smoke weed."

Wakka: "Do they smoke weed, ya?"

Yuna: "Yes, actually."

Lulu: "You mean she isn't just smoking a cigarette?"

Khimari: "Khimari don't know weed cigarettes."

Dressphere change: Dancer

Yuna: "It's called a phid... not weed cigarette..."

Yuna: "And yes, it is a weed phid. They all smoke weed phids before we kiss. (They are my girlfriends,)"

Wakka: "Do they smoke weed, ya?"

Yuna: "Yes, actually."

Lulu: "You mean she isn't just smoking a cigarette?"

Khimari: "Khimari don't know weed cigarettes."

Dressphere change: Dancer

Yuna: "It's called a phid... not weed cigarette..."

Yuna: "And yes, it is a weed phid. They all smoke weed phids before we kiss. (They are my girlfriends,)"

Saboten Bombers

1992

I watch the funny cacti boundin', gyrating on screen, racking up points faster than a day trader, and I just think they're neat. /marge

Other reviews have pointed out how Saboten Bombers takes after Snow Bros. or the much earlier Bubble Bobble mold of single-screen elimination platformers. To me, knowing a few things about NMK's catalog, this brought something like Buta-san to mind first. The developer was no stranger to iterating on notable contemporaries like Bomberman, having removed that series' mazes in favor of open-range puzzle combat. Now we have a more conventional take on the genre, albeit with its own unmistakable zest. Simply put, filling the screen with balls of explosive fun couldn't be more pivotal and delightful than in a game like this.

Those '80s pigs' carefully-timed bombs are traded in fun for chaotic physics and the (relatively) unique mechanic of traveling within your projectiles. It's a risky and rewarding proposition to the player: do you lob the balls from a comfortable position, never getting into the thick of it, or is riding into the fray to score higher and faster more your thing? Saboten Bombers does a great job of letting players adapt to the cadence of each stage, allowing both safety and surprise attacks on these floral & faunal interlopers. Much like the whack-a-mole rhythm found in Buta-san, most foes tend to waddle around and languish until finally prepping any attacks, so the difficulty curve here is also friendlier than you'd expect for an early-'90s cabinet game.

Trouble is, there's really not a lot of variance in play and content to justify the length for a 1CC, or even just feeding through to the end. Clearing Buta-san takes scarcely more than 15 or so minutes, yet this can go past an hour even with quick, skillful tactics. One can get a vertical slice of this '92 bonanza in less than 300 seconds, and a lot of repetition sets in around the 25 to 30 minute mark. Of course, I'd never play something like Saboten Bombers simply to see all the major enemies, settings, and situations it throws at you. This genre's all about taking big chances for big prizes, and so the adrenaline and unexpected humor in this particular game shores up these other problems. It's hard to really hold the few types of baddies and predictable stage layouts against this ROM given it's best played and learned in spurts.

NMK almost always had to punch above its weight, making idiosyncratic forays within a market often dominated by Taito, SEGA, Konami, Capcom, etc. So it's cool to see all the little details they crammed in here which liven up an already cute and inviting action-platformer. Each critter's got smooth, stretchy animation with tons of frames and rare idle variations. The color palette's rich beyond its years, looking like something made for Sega Saturn later in the decade. And while Saboten Bombers wisely avoids shoving in huge sprites for the sake of it, every design's readable at a glance and has plenty of meaningful detail. So even if an expert playthrough will end up repeating itself, all this meticulous production ensures it won't feel that stale.

Add in two kinds of boss stages, a ridiculously detailed (if opaque) scoring system, and one of those crunchy, catchy PCM-only soundtracks for a delicious time overall. Maybe there are more polished examples of this style of scrappy screen-clearing software snack. I'm not yet experienced enough with this era to highlight them, though, so any bit of cruft I found here is possibly more palatable as a result. What can I say other than that Saboten Bombers nails both the essentials and many extra you'd hope for in anything this straightforward? Sometimes all you need are pyrotechnics, pizzaz, and wacky fruit collecting all inside the family restroom. These electronic eudicots have nothing better to do than trash the place, and I'm all here for that!

Completed for the Backloggd Discord server’s Game of the Week club, Mar. 14 - 20, 2023

Other reviews have pointed out how Saboten Bombers takes after Snow Bros. or the much earlier Bubble Bobble mold of single-screen elimination platformers. To me, knowing a few things about NMK's catalog, this brought something like Buta-san to mind first. The developer was no stranger to iterating on notable contemporaries like Bomberman, having removed that series' mazes in favor of open-range puzzle combat. Now we have a more conventional take on the genre, albeit with its own unmistakable zest. Simply put, filling the screen with balls of explosive fun couldn't be more pivotal and delightful than in a game like this.

Those '80s pigs' carefully-timed bombs are traded in fun for chaotic physics and the (relatively) unique mechanic of traveling within your projectiles. It's a risky and rewarding proposition to the player: do you lob the balls from a comfortable position, never getting into the thick of it, or is riding into the fray to score higher and faster more your thing? Saboten Bombers does a great job of letting players adapt to the cadence of each stage, allowing both safety and surprise attacks on these floral & faunal interlopers. Much like the whack-a-mole rhythm found in Buta-san, most foes tend to waddle around and languish until finally prepping any attacks, so the difficulty curve here is also friendlier than you'd expect for an early-'90s cabinet game.

Trouble is, there's really not a lot of variance in play and content to justify the length for a 1CC, or even just feeding through to the end. Clearing Buta-san takes scarcely more than 15 or so minutes, yet this can go past an hour even with quick, skillful tactics. One can get a vertical slice of this '92 bonanza in less than 300 seconds, and a lot of repetition sets in around the 25 to 30 minute mark. Of course, I'd never play something like Saboten Bombers simply to see all the major enemies, settings, and situations it throws at you. This genre's all about taking big chances for big prizes, and so the adrenaline and unexpected humor in this particular game shores up these other problems. It's hard to really hold the few types of baddies and predictable stage layouts against this ROM given it's best played and learned in spurts.

NMK almost always had to punch above its weight, making idiosyncratic forays within a market often dominated by Taito, SEGA, Konami, Capcom, etc. So it's cool to see all the little details they crammed in here which liven up an already cute and inviting action-platformer. Each critter's got smooth, stretchy animation with tons of frames and rare idle variations. The color palette's rich beyond its years, looking like something made for Sega Saturn later in the decade. And while Saboten Bombers wisely avoids shoving in huge sprites for the sake of it, every design's readable at a glance and has plenty of meaningful detail. So even if an expert playthrough will end up repeating itself, all this meticulous production ensures it won't feel that stale.

Add in two kinds of boss stages, a ridiculously detailed (if opaque) scoring system, and one of those crunchy, catchy PCM-only soundtracks for a delicious time overall. Maybe there are more polished examples of this style of scrappy screen-clearing software snack. I'm not yet experienced enough with this era to highlight them, though, so any bit of cruft I found here is possibly more palatable as a result. What can I say other than that Saboten Bombers nails both the essentials and many extra you'd hope for in anything this straightforward? Sometimes all you need are pyrotechnics, pizzaz, and wacky fruit collecting all inside the family restroom. These electronic eudicots have nothing better to do than trash the place, and I'm all here for that!

Completed for the Backloggd Discord server’s Game of the Week club, Mar. 14 - 20, 2023

Fallout: New Vegas

2010

This review contains spoilers

Some say he tore through the Mojave, a revenant hellbent on destruction. Others claimed she burned with righteous glory, a beacon of justice scorching the unjust, and others still claim they were just a kleptomaniac out to have a good time. Hell, I’ve heard they fell through the earth and woke up in D.C., that their mere presence would make you feel like your brain would stop processing, that they could carry a thousand pounds and run faster than the devil. End of the day, the trivia of the how and when barely matter as much as the “who”.

A decade ago, a batch of couriers set out with cargo bound to New Vegas. The whole lot of them carried worthless trinkets across the sands, a batch of diversions and a single Platinum Chip. Five couriers made it to New Vegas unscathed. Lady Luck must have had it out for the last poor bastard; the only package that mattered was signed off with two shots to the head and a shallow grave. That should’ve been the end of it, another nameless body lost to wasteland, but be it by fate, fury or spite, the dead man walked. Wasn't even two days later that the thief in the checkered suit was gunned down, 9mm justice ringing red hot. Within a week, President Kimball lost his head, the Followers of the Apocalypse were a smoking crater, the Brotherhood of Steel suffered a fatal error, and Caesar himself fell to the knife's edge. Crazy son of a gun even took the Strip by siege, running some police state ops under the table. Or at least, that's how I've heard it told.

When all is said and done, the devil's in the details. The Courier was just as much a sinner as a saint, but anyone could tell you that. Hell, I'd go as far as to say the moment-to-moment minutia doesn't matter; who cares that she traveled with a former 1st Recon sniper, or a whisky-chugging cowpoke? Will anyone remember the ghoul mechanic, the robo-dog, the Enclave reject, or the schizophrenic Nightkin?

No, even as the figurehead of The Strip, no one can really pin down the story in a way everyone can agree on. You'll hear a thousand stories, and the only two consistent factors are that some poor delivery boy got his brains blown out, and that when the dust settled, the Mohave was never quite the same. But listen to me rattle on… you know all of this. After all, that's exactly how you wanted it, right?

When you picked that platinum chip off of Benny, riddled with holes, you knew what you were doing, didn't you? How could you not; it wasn't the first time you shot the boy down. Last time, it was a Ripper to the gut, this time his own gun to the back of the head. Did everyone every figure out how Maria was in your hand and in his back pocket? When the mighty Courier crushed the Great Khans beneath their heel, did you so much as flinch, or was this just another quest in your wild wasteland? Even with cannibals licking their lips with you in their eyes, you smiled, like this was an old joke reminding you of better times.

A decade ago, you woke up in Doc Mitchell's practice, head like a hole with a big iron on your hip. Now, you're back in Goodsprings. Everyone acts like this is new, fresh, like you haven't done this a thousand times over. I know this story, you know it even better. Still, it's hard to stop yourself from doing the same old song and dance, isn't it? For as much as patrolling the Mojave can make you wish for a nuclear winter, you keep coming back. It's not just war; nothing about the desert ever changes. But that's just how you like it, isn't it, Courier?

Vegas never changes. You never change.

A decade ago, a batch of couriers set out with cargo bound to New Vegas. The whole lot of them carried worthless trinkets across the sands, a batch of diversions and a single Platinum Chip. Five couriers made it to New Vegas unscathed. Lady Luck must have had it out for the last poor bastard; the only package that mattered was signed off with two shots to the head and a shallow grave. That should’ve been the end of it, another nameless body lost to wasteland, but be it by fate, fury or spite, the dead man walked. Wasn't even two days later that the thief in the checkered suit was gunned down, 9mm justice ringing red hot. Within a week, President Kimball lost his head, the Followers of the Apocalypse were a smoking crater, the Brotherhood of Steel suffered a fatal error, and Caesar himself fell to the knife's edge. Crazy son of a gun even took the Strip by siege, running some police state ops under the table. Or at least, that's how I've heard it told.

When all is said and done, the devil's in the details. The Courier was just as much a sinner as a saint, but anyone could tell you that. Hell, I'd go as far as to say the moment-to-moment minutia doesn't matter; who cares that she traveled with a former 1st Recon sniper, or a whisky-chugging cowpoke? Will anyone remember the ghoul mechanic, the robo-dog, the Enclave reject, or the schizophrenic Nightkin?

No, even as the figurehead of The Strip, no one can really pin down the story in a way everyone can agree on. You'll hear a thousand stories, and the only two consistent factors are that some poor delivery boy got his brains blown out, and that when the dust settled, the Mohave was never quite the same. But listen to me rattle on… you know all of this. After all, that's exactly how you wanted it, right?

When you picked that platinum chip off of Benny, riddled with holes, you knew what you were doing, didn't you? How could you not; it wasn't the first time you shot the boy down. Last time, it was a Ripper to the gut, this time his own gun to the back of the head. Did everyone every figure out how Maria was in your hand and in his back pocket? When the mighty Courier crushed the Great Khans beneath their heel, did you so much as flinch, or was this just another quest in your wild wasteland? Even with cannibals licking their lips with you in their eyes, you smiled, like this was an old joke reminding you of better times.

A decade ago, you woke up in Doc Mitchell's practice, head like a hole with a big iron on your hip. Now, you're back in Goodsprings. Everyone acts like this is new, fresh, like you haven't done this a thousand times over. I know this story, you know it even better. Still, it's hard to stop yourself from doing the same old song and dance, isn't it? For as much as patrolling the Mojave can make you wish for a nuclear winter, you keep coming back. It's not just war; nothing about the desert ever changes. But that's just how you like it, isn't it, Courier?

Vegas never changes. You never change.

Saboten Bombers

1992

「今日はいたずらなサボテンや害虫からご主人様のお留守をお守りしようと、鉢植えを飛び出して戦い始めました。」

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (Mar. 14 – Mar. 20, 2023).

The undeniable success of Bubble Bobble (1986) had spawned many sequels and derivatives, both from Taito and other publishers. One such title that proved popular with some audiences in the West was Toaplan's Snow Bros. (1990), in which the objective was to throw snow at enemies to create a large snowball that the player could roll at other opponents. This concept was revisited by NMK in 1992, resulting in Saboten Bombers, which would not be released outside of Japan until the Switch port in 2021. Players assume the role of cacti, Wanpi and Tsupi, protecting their master's mansion from insects and other evil plants. Just like in Snow Bros., players must eliminate all enemies on the screen without attacking them directly, but by throwing bombs at them. These bombs catch the enemies and carry them in their path before exploding after a certain amount of time. The objective is to maximise points by catching as many enemies as possible before the bomb detonates.

While Snow Bros. had the same obsession with scoring, the title allowed for more deliberate positioning and execution, as the trajectory of the snowballs was easier to gauge. They often just rolled across the platforms, following the natural movement of gravity. In Saboten Bombers, the atmosphere is much more chaotic: the bombs bounce around a lot and often stay at the same height, so the player has to be very careful not to get caught in their own explosion. Most of the levels are a cat-and-mouse game where one must quickly determine their angle of attack before avoiding the myriad explosions on the screen. This anarchic frenzy takes a while to get used to, as it relies so heavily on the player's ability to react quickly, but it suits perfectly with the title's gummy-pop flair. There is something charming about seeing plants and insects running around with exaggerated movements and throwing bombs at each other, contrasting with the peacefulness of the environments, which could easily be mistaken for PC-Engine visual novel backgrounds.

Every five stages, the classic levels are interspersed with a battle between the two players – or the player and the CPU if playing alone – or a boss fight. The former work well, as they capitalise on the chaos inherent in the gameplay, but the latter are a little more mixed. While Snow Bros. also struggled slightly with these boss sequences, they were more natural, as they involved figuring out the method to defeat the boss while avoiding being trapped by the enemies. At worst, they were sections that borrowed the traditional grammar of arcade action-platformer bosses, namely painless and forgettable encounters. In Saboten Bombers, the most annoying factor is the awkward trajectory of the bombs, halfway between a high trajectory and a ground shot. The boss fights are thus generally uninteresting, as they do not build on the verticality or the bounce of the bombs. Fortunately, these sequences are relatively rare and thus innocuous.

The main attraction of the title is the scoring system, which can be as subtle as it is esoteric. Aside from the secret tricks and techniques – for example, allowing the timer to run out causes a shower of bombs to explode on the screen; staying alive earns a significant scoring bonus – efficient routing and intelligent use of power-ups make for an exhilarating experience, as the player dodges the many explosions that blossom on the screen. There is an absurd, candy-coated poetry to Saboten Bombers. Why it didn't benefit from a Western localisation, unlike other NMK games, is unclear; perhaps the elimination platformer craze was not yet consolidated enough in the early 1990s. Either way, Saboten Bombers remains a pleasant little curiosity, distinct from the shoot'em ups and adventure games for which the company is generally known.

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (Mar. 14 – Mar. 20, 2023).

The undeniable success of Bubble Bobble (1986) had spawned many sequels and derivatives, both from Taito and other publishers. One such title that proved popular with some audiences in the West was Toaplan's Snow Bros. (1990), in which the objective was to throw snow at enemies to create a large snowball that the player could roll at other opponents. This concept was revisited by NMK in 1992, resulting in Saboten Bombers, which would not be released outside of Japan until the Switch port in 2021. Players assume the role of cacti, Wanpi and Tsupi, protecting their master's mansion from insects and other evil plants. Just like in Snow Bros., players must eliminate all enemies on the screen without attacking them directly, but by throwing bombs at them. These bombs catch the enemies and carry them in their path before exploding after a certain amount of time. The objective is to maximise points by catching as many enemies as possible before the bomb detonates.

While Snow Bros. had the same obsession with scoring, the title allowed for more deliberate positioning and execution, as the trajectory of the snowballs was easier to gauge. They often just rolled across the platforms, following the natural movement of gravity. In Saboten Bombers, the atmosphere is much more chaotic: the bombs bounce around a lot and often stay at the same height, so the player has to be very careful not to get caught in their own explosion. Most of the levels are a cat-and-mouse game where one must quickly determine their angle of attack before avoiding the myriad explosions on the screen. This anarchic frenzy takes a while to get used to, as it relies so heavily on the player's ability to react quickly, but it suits perfectly with the title's gummy-pop flair. There is something charming about seeing plants and insects running around with exaggerated movements and throwing bombs at each other, contrasting with the peacefulness of the environments, which could easily be mistaken for PC-Engine visual novel backgrounds.

Every five stages, the classic levels are interspersed with a battle between the two players – or the player and the CPU if playing alone – or a boss fight. The former work well, as they capitalise on the chaos inherent in the gameplay, but the latter are a little more mixed. While Snow Bros. also struggled slightly with these boss sequences, they were more natural, as they involved figuring out the method to defeat the boss while avoiding being trapped by the enemies. At worst, they were sections that borrowed the traditional grammar of arcade action-platformer bosses, namely painless and forgettable encounters. In Saboten Bombers, the most annoying factor is the awkward trajectory of the bombs, halfway between a high trajectory and a ground shot. The boss fights are thus generally uninteresting, as they do not build on the verticality or the bounce of the bombs. Fortunately, these sequences are relatively rare and thus innocuous.

The main attraction of the title is the scoring system, which can be as subtle as it is esoteric. Aside from the secret tricks and techniques – for example, allowing the timer to run out causes a shower of bombs to explode on the screen; staying alive earns a significant scoring bonus – efficient routing and intelligent use of power-ups make for an exhilarating experience, as the player dodges the many explosions that blossom on the screen. There is an absurd, candy-coated poetry to Saboten Bombers. Why it didn't benefit from a Western localisation, unlike other NMK games, is unclear; perhaps the elimination platformer craze was not yet consolidated enough in the early 1990s. Either way, Saboten Bombers remains a pleasant little curiosity, distinct from the shoot'em ups and adventure games for which the company is generally known.

Osman

1996

shit goes crazy why nobody said nothin? important reclamation fiction of what shoulda happened after the #8 seed franks upset the #1 seed umayyads at the battle of tours: the legacy of the caliphates, mythologized into a assassin quasi-prophet who kicks really hard and fast, spinnin back to hit a vicious stain on the now globalized "West" and "Neoliberalism" across 5 side-scroller stages. look i know "the west & neoliberalism" mean absolutely nothing beyond "uh america & profits" in the current critical landscape but the opps here are the Federal Government (proper noun) and an Attorney General who double crosses you after using you to put down a religious cult in the Persian Gulf. shits like a silver bullet made for the Bush family's headtop and a very personal short call of the Dollar System as far as political specificity in video games go. contra strider, osman asks you to put the weapon down and beat ass with two hands and feet--you'll be sliding n gliding n crouching through the mud like any side scroller but the greatest mechanic here is the afterimage system. each powerup you get gives you an brief stationary clone that'll stay in your last attack spot and synchronize with your attack inputs for the next few seconds. seems strong enough right, but the real trick is to plant like 8 of these clones right in somebody's hurtbox, run away, then start whiffing like a ken player to trigger all 8 of those attack clones at once and deal unconscious amounts of damage in quick succession. nomiss runs of this are like 15 minutes because of how much burst damage you can put out in addition to the bombs--bosses here can go out sad in like 20 seconds if you've been on it in keeping your powerups & bombs available. was this intended? maybe, but it made avoiding any death to keep my resources really critical, and some sense of tension along with unhinged ingenuity is all i ask from the MAME experience these days n i got it in spades. there's also some metatext here but honestly just taking this shit at face value was a joy. prescient in recognizing the global south is where the revolution at and we're just kinda pussy.

Overwatch 2

2022

Cleansed by the surf, a body washes ashore on a deserted beach. Nameless, this soul awakens, eyes gleaming with the will to live, and for all things worth living for.

This was my first full playthrough of the game since maybe 2013, and the first time I’ve tackled the expansion content added to the Dark Arisen release. Game still rocks my world. Something of a Capcom dream team coming together to create a moving Frazetta artwork. Hideaki Itsuno’s combat direction acumen and some Monhun crew in the wings to reign the madness into a more grounded dark fantasy action game with a keen eye for resource management & an iconique soundtrack. An excitable exploration of pure western fantasy through the Japanese lens akin to Record of Lodoss War.

I really do just think it’s special. Every excursion through the world or a dungeon is speckled with emergent Moments that can only come around because the systems the game is built on offer a wealth of synergies and expressive means of interactivity. The regularity with which Dragon’s Dogma punctuates an excursion with sick as hell moments that steal your breath, as well as pure slapstick comedy, it almost rivals a particularly haphazard TTRPG campaign. It pays to take note of enemy AI behaviors and exploits, because your pawns will learn as you do and take actions that repeatedly surprise - when I started picking throwing loose enemies into the wider horde in order to more easily deal AoE damage, I noticed my pawn starting to do it for me and I felt like a proud dad.

The world of Gransys is almost my platonic ideal open-world RPG setting. With transportation options limited, the relatively small scale of the map itself is made to feel gargantuan, aided by the density to which it is decorated with places of interest and rewards for clambering up suspicious nooks. Questing requires planning so careful that even a journey down a road must be approached with trepidation. All with thanks to the game’s downright brutal day-night cycle with realistic lighting, you enter a pitch black forest with only your lantern and the reflection of the starving beastly eyes peering at you through the shrubbery. It was impressive in 2012, and remains so to this very day imo!!! I’ll never ever in my life forget the way I shot out of my chair because I turned on my lantern in the pitch black, to reveal the face of a gargantuan chimera winding up a punch.

Dark Arisen offers a locale with something of a megadungeon populated by new enemies and threats. Some of the most fun I’ve ever had with the game occurred within those dingy stone walls. It feels almost like a Bloody Palace mode so you can unleash your classbuilding prowess on the increasingly monstrous beasties thrown your way. End boss was some pure “ah, so this is why games exist” affirmation, too.

…But, it’s undeniably as half-baked as the rest of the game itself. Dragon’s Dogma feels about as unfinished as I’d dejectedly expect anything that comes across as a double-A passion project to be. Brimming with brave creative flourishes, but lacking in a certain star power to really let it raise the bar. I don’t want to beat the dead horse and lament the concepts on the cutting room floor, but it’s fairly noticeable that the game suffers from an enemy and location variety deficit. The implementation of the Pawn system is downright amazing, but so peculiar with miniscule blink-and-you’ll-miss-it details that they don’t have much of a cohesive bigger picture place in the game, and come across as a patchwork solution to a botched multiplayer mode. The quests are fairly rote in and of themselves, and the characters - while I love their antiquated Tolkienist dialogue style, are all flat and unmemorable. Even the classes themselves, which I’d still say are near-enough goated as far as fantasy action games are concerned, could do with a little more in the way of skill diversity. Bitterblack Isle itself feels like at most five unique rooms repeated a handful of times.

Still, don’t wanna be a downer. Dragon’s Dogma is amazing, scratches such a specific itch that I can only thank The Maker that it even exists in the way it does at all. Didn't mention the story at all, not sure how I'd tackle it honestly - thematically rich and insanely well executed. Grigori gets me weak at the knees, man. How the fuck is this game getting a sequel, nothing I like is ever allowed to do that.

This was my first full playthrough of the game since maybe 2013, and the first time I’ve tackled the expansion content added to the Dark Arisen release. Game still rocks my world. Something of a Capcom dream team coming together to create a moving Frazetta artwork. Hideaki Itsuno’s combat direction acumen and some Monhun crew in the wings to reign the madness into a more grounded dark fantasy action game with a keen eye for resource management & an iconique soundtrack. An excitable exploration of pure western fantasy through the Japanese lens akin to Record of Lodoss War.

I really do just think it’s special. Every excursion through the world or a dungeon is speckled with emergent Moments that can only come around because the systems the game is built on offer a wealth of synergies and expressive means of interactivity. The regularity with which Dragon’s Dogma punctuates an excursion with sick as hell moments that steal your breath, as well as pure slapstick comedy, it almost rivals a particularly haphazard TTRPG campaign. It pays to take note of enemy AI behaviors and exploits, because your pawns will learn as you do and take actions that repeatedly surprise - when I started picking throwing loose enemies into the wider horde in order to more easily deal AoE damage, I noticed my pawn starting to do it for me and I felt like a proud dad.

The world of Gransys is almost my platonic ideal open-world RPG setting. With transportation options limited, the relatively small scale of the map itself is made to feel gargantuan, aided by the density to which it is decorated with places of interest and rewards for clambering up suspicious nooks. Questing requires planning so careful that even a journey down a road must be approached with trepidation. All with thanks to the game’s downright brutal day-night cycle with realistic lighting, you enter a pitch black forest with only your lantern and the reflection of the starving beastly eyes peering at you through the shrubbery. It was impressive in 2012, and remains so to this very day imo!!! I’ll never ever in my life forget the way I shot out of my chair because I turned on my lantern in the pitch black, to reveal the face of a gargantuan chimera winding up a punch.

Dark Arisen offers a locale with something of a megadungeon populated by new enemies and threats. Some of the most fun I’ve ever had with the game occurred within those dingy stone walls. It feels almost like a Bloody Palace mode so you can unleash your classbuilding prowess on the increasingly monstrous beasties thrown your way. End boss was some pure “ah, so this is why games exist” affirmation, too.

…But, it’s undeniably as half-baked as the rest of the game itself. Dragon’s Dogma feels about as unfinished as I’d dejectedly expect anything that comes across as a double-A passion project to be. Brimming with brave creative flourishes, but lacking in a certain star power to really let it raise the bar. I don’t want to beat the dead horse and lament the concepts on the cutting room floor, but it’s fairly noticeable that the game suffers from an enemy and location variety deficit. The implementation of the Pawn system is downright amazing, but so peculiar with miniscule blink-and-you’ll-miss-it details that they don’t have much of a cohesive bigger picture place in the game, and come across as a patchwork solution to a botched multiplayer mode. The quests are fairly rote in and of themselves, and the characters - while I love their antiquated Tolkienist dialogue style, are all flat and unmemorable. Even the classes themselves, which I’d still say are near-enough goated as far as fantasy action games are concerned, could do with a little more in the way of skill diversity. Bitterblack Isle itself feels like at most five unique rooms repeated a handful of times.

Still, don’t wanna be a downer. Dragon’s Dogma is amazing, scratches such a specific itch that I can only thank The Maker that it even exists in the way it does at all. Didn't mention the story at all, not sure how I'd tackle it honestly - thematically rich and insanely well executed. Grigori gets me weak at the knees, man. How the fuck is this game getting a sequel, nothing I like is ever allowed to do that.

Sweet as sugar.

Sweet as young love.

Sweet as can be.

Nostalgic and enraptured with youth as Norwegian Wood.

Magical and intertwined as Kafka on the Shore.

Two blurred lines proceeding apace in parallel as 1Q84.

Perfectly self contained within its own narrative.

Abound with the peculiarities of children.

Spare and sparse.

Father's guidance.

Mother's embrace.

One's own destiny.

Comfortable.

Joyful.

Warm.

Sweet as young love.

Sweet as can be.

Nostalgic and enraptured with youth as Norwegian Wood.

Magical and intertwined as Kafka on the Shore.

Two blurred lines proceeding apace in parallel as 1Q84.

Perfectly self contained within its own narrative.

Abound with the peculiarities of children.

Spare and sparse.

Father's guidance.

Mother's embrace.

One's own destiny.

Comfortable.

Joyful.

Warm.

Samus never really returned to my childhood gaming life since the day I first met them back on the NES, it was quite a hole there between that and 2002, aka The Year Metroid Beat Everyone's Ass. Metroid II for all intents and purposes was just the cover for the box of the Super Game Boy, that was everything I knew it as. Just the front of a piece of cardboard that I saw at some store or in a JC Penny catalog maybe. It existed, that's all I knew.

I have many bones to pick with the way Nintendo treats it's back catalog of classics and oddities, but if there's any silver lining to the dripfeed of past content it's finding a reason to finally give a serious go at Samus' mission to genocide a race of beings for the supposed sake of the galaxy. The final enemies that you were once scared of back on your original adventure are now the sole focus of your mission, and as it turns out those were just the little baby forms. The nightmarish vampire jellyfish can evolve into monstrosities that could no doubt devastate many a civilization.

This is a fight for survival on both ends, it's us or them. It's not pretty.

The sprites are huge and chunky, resulting in screen space being closed in on you. This isn't just the screen, this is the darkness that Samus must traverse as she delves deeper into SR388. There's no telling what's coming up, and you're allowed just the faintest sighting of a Metroid before it spots you and begins it's attack for you to contemplate a battle or to make a strategic retreat to restock. Missiles require more and more care as the Metroids grow stronger and more terrifying as fear begins settling more and more during your first venture into this journey, and the music joins in on making your life go from disturbing to downright hellish with one of my favorite scare chords in recent memory.

Metroid II is a milestone for gaming as a medium, it truly drives home the utter misery that is to carry out a mass killing of other living beings who wouldn't think a second thought to do the same thing to you and your loved ones. It is...dare I say, an early example of Survival Horror. I don't see this game brought up a lot, but it really leans into much of the same pillars of which that genre builds itself upon. You traverse unexplored maps, looking for either dangerous creatures that make your universal counter go down one by one, or energy and ammunition to keep yourself strong to carry out said objective with more confidence. Your little vacation at SR388 begins all fun and games, then only gets more and more visceral as it becomes apparent just how destructive the Metroids truly are with long pathways that bear little to zero life. Violence to end violence...and at the end of all the destruction, an innocent that you can't go through with the killing of....a shred of hope that peace could be theoretically achieved with these lifeforms still intact.

Peace Sells, I'm buying.

Over the course of the 2010s I used to hear a lot of hollering of this game requiring a remake. It got them, all two of them. Personally, I feel once you take the aesthetic of the Game Boy away from Metroid II it dampers the experience a smidgen and it's identity is lost. That fear isn't really there anymore and many AAA-isms get thrown in to make the experience more "epic", which puts a bit of a bad taste in my mouth when the original foundation was to be a legitimately Dreadful experience as opposed to Samus doing kickflips off an Omega Metroid and striking a pose for the camera as the cutscene does the actions for you. Maybe it's just my age showing, but considering I only got to play this seriously recently and formerly brushed it off myself, I think there's legitimacy behind it.

Give this one a go, wait for the sun to go down, close your curtains, and play this on your Switch while under your blanket in your room. Simulate that feeling of a child playing this haunting game alone with only the sounds of that experimental atmospheric soundtrack going off as you wander the caverns of SR388. Perhaps even get a worm light on a Game Boy Color to get the ultimate experience. I don't think you'll regret it. It's an experience I wish I grew up with.

Respect the originals, don't replace them. Admire them.

I have many bones to pick with the way Nintendo treats it's back catalog of classics and oddities, but if there's any silver lining to the dripfeed of past content it's finding a reason to finally give a serious go at Samus' mission to genocide a race of beings for the supposed sake of the galaxy. The final enemies that you were once scared of back on your original adventure are now the sole focus of your mission, and as it turns out those were just the little baby forms. The nightmarish vampire jellyfish can evolve into monstrosities that could no doubt devastate many a civilization.

This is a fight for survival on both ends, it's us or them. It's not pretty.

The sprites are huge and chunky, resulting in screen space being closed in on you. This isn't just the screen, this is the darkness that Samus must traverse as she delves deeper into SR388. There's no telling what's coming up, and you're allowed just the faintest sighting of a Metroid before it spots you and begins it's attack for you to contemplate a battle or to make a strategic retreat to restock. Missiles require more and more care as the Metroids grow stronger and more terrifying as fear begins settling more and more during your first venture into this journey, and the music joins in on making your life go from disturbing to downright hellish with one of my favorite scare chords in recent memory.

Metroid II is a milestone for gaming as a medium, it truly drives home the utter misery that is to carry out a mass killing of other living beings who wouldn't think a second thought to do the same thing to you and your loved ones. It is...dare I say, an early example of Survival Horror. I don't see this game brought up a lot, but it really leans into much of the same pillars of which that genre builds itself upon. You traverse unexplored maps, looking for either dangerous creatures that make your universal counter go down one by one, or energy and ammunition to keep yourself strong to carry out said objective with more confidence. Your little vacation at SR388 begins all fun and games, then only gets more and more visceral as it becomes apparent just how destructive the Metroids truly are with long pathways that bear little to zero life. Violence to end violence...and at the end of all the destruction, an innocent that you can't go through with the killing of....a shred of hope that peace could be theoretically achieved with these lifeforms still intact.

Peace Sells, I'm buying.

Over the course of the 2010s I used to hear a lot of hollering of this game requiring a remake. It got them, all two of them. Personally, I feel once you take the aesthetic of the Game Boy away from Metroid II it dampers the experience a smidgen and it's identity is lost. That fear isn't really there anymore and many AAA-isms get thrown in to make the experience more "epic", which puts a bit of a bad taste in my mouth when the original foundation was to be a legitimately Dreadful experience as opposed to Samus doing kickflips off an Omega Metroid and striking a pose for the camera as the cutscene does the actions for you. Maybe it's just my age showing, but considering I only got to play this seriously recently and formerly brushed it off myself, I think there's legitimacy behind it.

Give this one a go, wait for the sun to go down, close your curtains, and play this on your Switch while under your blanket in your room. Simulate that feeling of a child playing this haunting game alone with only the sounds of that experimental atmospheric soundtrack going off as you wander the caverns of SR388. Perhaps even get a worm light on a Game Boy Color to get the ultimate experience. I don't think you'll regret it. It's an experience I wish I grew up with.

Respect the originals, don't replace them. Admire them.

Resident Evil

2002

An absolute masterpiece. Every detail, whether through design, gameplay, or story, is so clearly well thought out, it comes together to create the perfect horror game. Resident Evil flourishes on its scary environment without ever relying on the cheapness of jump scares to enforce these vibes. It takes the best aspects of storytelling and gameplay and perfects them to create an absolutely brilliant survival horror game.

The entire game is designed around boosting every element of a video game to best fit the scary environment. It knows that as a horror game you'll be wanting to save as often as you're able, allowing yourself the extra security while walking around the murderous environment. Thus they add in the element of save ribbons; something simple that seems tedious at first but adds incredible thrill as you continue to play. You play the game faster as you're not saving as often in order to save ribbons, in fact it does the unimaginable and gets the player comfortable in not saving. The puzzles throughout are simply perfect. They're simple enough to not cause frustration, but not so braindead they bore the player. Walking the hallways even are a puzzle within themselves, knowing which zombies are more important to focus on burning and avoiding in order to conserve bullets. Every moment of the game involves thinking about your next step, keeping you on your tiptoes from the horror aspect, while also keeping players excited for the next clue in solving the mystery of the mansion. Keeping track of inventory spaces even, becomes a part of the puzzle of your eventual escape.

Talking about the game can't go without mentioning how beautiful it looks. The fact this remaster is on the GameCube looking as gorgeous as it does is shocking. Tank controls allow the camera to cut in cinematic ways, as well as giving the player breathing time between rooms with great shots of the doors in-between, each one personalized to the story. I disagree with complaints of them, as I feel it creates an incredibly artistic atmosphere of mixing both film horror techniques and classic first-person video game ambience.

Overall, Resident Evil is a breathtaking game. An absolute must-play. A classic of video game history.

And most important of all, it looked freaking great on my princess TV.

The entire game is designed around boosting every element of a video game to best fit the scary environment. It knows that as a horror game you'll be wanting to save as often as you're able, allowing yourself the extra security while walking around the murderous environment. Thus they add in the element of save ribbons; something simple that seems tedious at first but adds incredible thrill as you continue to play. You play the game faster as you're not saving as often in order to save ribbons, in fact it does the unimaginable and gets the player comfortable in not saving. The puzzles throughout are simply perfect. They're simple enough to not cause frustration, but not so braindead they bore the player. Walking the hallways even are a puzzle within themselves, knowing which zombies are more important to focus on burning and avoiding in order to conserve bullets. Every moment of the game involves thinking about your next step, keeping you on your tiptoes from the horror aspect, while also keeping players excited for the next clue in solving the mystery of the mansion. Keeping track of inventory spaces even, becomes a part of the puzzle of your eventual escape.

Talking about the game can't go without mentioning how beautiful it looks. The fact this remaster is on the GameCube looking as gorgeous as it does is shocking. Tank controls allow the camera to cut in cinematic ways, as well as giving the player breathing time between rooms with great shots of the doors in-between, each one personalized to the story. I disagree with complaints of them, as I feel it creates an incredibly artistic atmosphere of mixing both film horror techniques and classic first-person video game ambience.

Overall, Resident Evil is a breathtaking game. An absolute must-play. A classic of video game history.

And most important of all, it looked freaking great on my princess TV.

‘There was no shouting or pushing: indeed, voices were scarcely raised above an eager whisper.’

– Clive Barker, 'In the Hills, the Cities', in Books of Blood, vol. 1, 1984.

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (Feb. 28 – Mar. 6, 2023).

The releases of Go to Hell (1985) and Soft & Cuddly (1987) were part of a turning point in British computer history. The £125 cost of the ZX Spectrum made it a cheap microcomputer for the British public, and a community had quickly formed, with many video game creators. This was a period of intense creative activity, as it coincided with the Microelectronics Education Programme (1980-1986), which aimed to popularise computers among a younger audience, while the National Development Programme in Computer Aided Learning (1973-1977) was primarily intended for tertiary education. For John George Jones, the development of his games was a way of killing time: according to the strange interview he gave to Sinclair User, he was first and foremost a disillusioned musician who wanted to amuse himself with people's reactions to the violence of his games before returning to other activities that would interest him more. [1] There was no big project behind it, no real desire to push the boundaries of video game design, just a feeling of boredom.

Just as there is a certain irony in those who claim to be Nietzscheans by agreeing with truncated passages of the philosopher – Walter Kauffman pointed out that to be a Nietzschean is not to be a Nietzschean, as Nietzsche always urged his readers never to adhere to dogmas, including his own – so the idea of a sequel to Go to Hell and Soft & Cuddly may seem contradictory. In an age of normalised violence and gore in video game production, how does one capture the spirit of games made to shock the public? Detchibe pointed out that the splatterpunk aesthetic is far less shocking today than Jones' games were. The violence of The Light at the End (1986) was shocking and innovative for its time – Stephen King was also explicit in Carrie (1974), but always stopped short of the unbearable – but it was justified by a critique of the Reagan era and the perception that the working class was incapable of rebuilding a cohesive community.

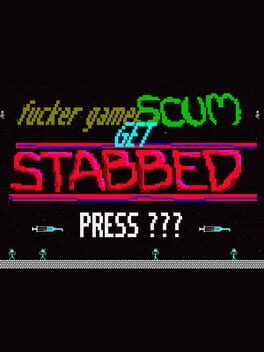

Fucker Gamer Scum Get Stabbed is at the crossroads of these aesthetic movements, more splat than punk, but it fails to evoke any emotion other than tedium. Many of the sprites are directly taken from Go to Hell, without the staging making them stand out. In Soft & Cuddly, there is a certain discomfort in seeing sickly, disfigured sprites covering the entire screen; in Go to Hell, the wide eyes staring at the player are unsettling, as they are stuck exploring a very gritty maze. Fucker Gamer Scum Get Stabbed is a short experience in which the player has no time to pause and observe and be impressed by the various scenes. There are no creative flights, no terrifying inspirations. For a few minutes, the player wanders through a pseudo-labyrinth in search of a red key, and it is enough to navigate randomly for a few more seconds to reach the exit. The protagonist is greeted in a circular room and laid on a hospital bed, surrounded by creatures created by Jones. At the top, an enemy reminds us that 'punks die'. Ironically, this echoes an interview with John Skipp in which he lamented the situation: ‘People seized on the splat, but forgot the punk. Which is to say, the subversive element. [...] I think a lot of people missed the fucking point entirely. It’s not just about how horrible you can make things. It’s about what it means. Why it matters. And what it says about us as a species.’ [2]

__________

[1] Sinclair User, no. 67, October 1987, p. 37

[2] ‘John Skipp & Shane Mckenzie – Talk Horror Interview’, in Splatterpunk, no. 4, November 2013.

– Clive Barker, 'In the Hills, the Cities', in Books of Blood, vol. 1, 1984.

Played during the Backloggd’s Game of the Week (Feb. 28 – Mar. 6, 2023).

The releases of Go to Hell (1985) and Soft & Cuddly (1987) were part of a turning point in British computer history. The £125 cost of the ZX Spectrum made it a cheap microcomputer for the British public, and a community had quickly formed, with many video game creators. This was a period of intense creative activity, as it coincided with the Microelectronics Education Programme (1980-1986), which aimed to popularise computers among a younger audience, while the National Development Programme in Computer Aided Learning (1973-1977) was primarily intended for tertiary education. For John George Jones, the development of his games was a way of killing time: according to the strange interview he gave to Sinclair User, he was first and foremost a disillusioned musician who wanted to amuse himself with people's reactions to the violence of his games before returning to other activities that would interest him more. [1] There was no big project behind it, no real desire to push the boundaries of video game design, just a feeling of boredom.

Just as there is a certain irony in those who claim to be Nietzscheans by agreeing with truncated passages of the philosopher – Walter Kauffman pointed out that to be a Nietzschean is not to be a Nietzschean, as Nietzsche always urged his readers never to adhere to dogmas, including his own – so the idea of a sequel to Go to Hell and Soft & Cuddly may seem contradictory. In an age of normalised violence and gore in video game production, how does one capture the spirit of games made to shock the public? Detchibe pointed out that the splatterpunk aesthetic is far less shocking today than Jones' games were. The violence of The Light at the End (1986) was shocking and innovative for its time – Stephen King was also explicit in Carrie (1974), but always stopped short of the unbearable – but it was justified by a critique of the Reagan era and the perception that the working class was incapable of rebuilding a cohesive community.

Fucker Gamer Scum Get Stabbed is at the crossroads of these aesthetic movements, more splat than punk, but it fails to evoke any emotion other than tedium. Many of the sprites are directly taken from Go to Hell, without the staging making them stand out. In Soft & Cuddly, there is a certain discomfort in seeing sickly, disfigured sprites covering the entire screen; in Go to Hell, the wide eyes staring at the player are unsettling, as they are stuck exploring a very gritty maze. Fucker Gamer Scum Get Stabbed is a short experience in which the player has no time to pause and observe and be impressed by the various scenes. There are no creative flights, no terrifying inspirations. For a few minutes, the player wanders through a pseudo-labyrinth in search of a red key, and it is enough to navigate randomly for a few more seconds to reach the exit. The protagonist is greeted in a circular room and laid on a hospital bed, surrounded by creatures created by Jones. At the top, an enemy reminds us that 'punks die'. Ironically, this echoes an interview with John Skipp in which he lamented the situation: ‘People seized on the splat, but forgot the punk. Which is to say, the subversive element. [...] I think a lot of people missed the fucking point entirely. It’s not just about how horrible you can make things. It’s about what it means. Why it matters. And what it says about us as a species.’ [2]

__________

[1] Sinclair User, no. 67, October 1987, p. 37

[2] ‘John Skipp & Shane Mckenzie – Talk Horror Interview’, in Splatterpunk, no. 4, November 2013.