Squigglydot

2010

When I was a kid, around fall my family would always plan big camping trips up north. After a decade and a half, the exact locales blur, all dirt campsites and sleepy towns, cut by endless drives down quiet backroads. Connecting every single trip, however, is the same singular image: laying in the backseat, staring to the sky as the pine, beech and maple trees ebbed and flowed with the breeze, a shimmer of greens, golds and reds against a still, cloudless ether.

Despite its northwestern setting, Alan Wake is a game that feels like home. Beyond the woodsy vibes, the spirit of the game keeps that same autumnal energy I associate with those countless trips, down to the same Halloween haunts that filled hours of my life. Alan Wake is read through the lens of Steven King and The Twilight Zone, a sort of contemporary / old school horror fusion, and the game makes it's infatuation with these influences blatant, to the point of embarrassment.

Horror molds the story and setting, leaning into a gun-toting Twin Peaks atmosphere, but the mold is not the full experience. Despite billing itself as a horror game, it feels more aligned with being an acknowledgement of horror's influence. In a sense, Alan Wake isn't a horror game; it's a game about horror, where horror itself is light and breezy.

Alan Wake is a beautiful game, a picturesque capturing of the woods and towns I spent much of my childhood in. To imply the game is mechanical deep or systematically unique would be disingenuous, but as a reflection of some of the most calming, perfect moments of my life, it's flawless. I love this game.

Despite its northwestern setting, Alan Wake is a game that feels like home. Beyond the woodsy vibes, the spirit of the game keeps that same autumnal energy I associate with those countless trips, down to the same Halloween haunts that filled hours of my life. Alan Wake is read through the lens of Steven King and The Twilight Zone, a sort of contemporary / old school horror fusion, and the game makes it's infatuation with these influences blatant, to the point of embarrassment.

Horror molds the story and setting, leaning into a gun-toting Twin Peaks atmosphere, but the mold is not the full experience. Despite billing itself as a horror game, it feels more aligned with being an acknowledgement of horror's influence. In a sense, Alan Wake isn't a horror game; it's a game about horror, where horror itself is light and breezy.

Alan Wake is a beautiful game, a picturesque capturing of the woods and towns I spent much of my childhood in. To imply the game is mechanical deep or systematically unique would be disingenuous, but as a reflection of some of the most calming, perfect moments of my life, it's flawless. I love this game.

2023

Latest game by me. A collaborative effort between Woodaba and I on writing, as well as ConeClvtist on music, and Vis and a mutual friend of Cone's and I on art.

I'm leaving this one pretty happy, all things considered; It really stands as something where I could feel everyone firing on all cylinders, and at around 22k words, it definitely breaks a bit of the mold of my last two games. With that said, it's really showing the limits of twine, as an engine. I love it, I will continue to use it, but for anything beyond a one-or-two person affair, creating with Twine proves to be... less than ideal.

In any case, still very glad to have done thing, and really, REALLY impressed by the work my fellows devs put into it.

And yeah I'm giving it a 5 anyway, i am shameless lol

I'm leaving this one pretty happy, all things considered; It really stands as something where I could feel everyone firing on all cylinders, and at around 22k words, it definitely breaks a bit of the mold of my last two games. With that said, it's really showing the limits of twine, as an engine. I love it, I will continue to use it, but for anything beyond a one-or-two person affair, creating with Twine proves to be... less than ideal.

In any case, still very glad to have done thing, and really, REALLY impressed by the work my fellows devs put into it.

And yeah I'm giving it a 5 anyway, i am shameless lol

2009

The surface charm of Bayonetta, a hypersexualized spectacle, belies a sadistic seduction, the pinnacle of character action gameplay gate-kept by the genre's tradition of ball-busting difficulty. Taking after it's spindly namesake, the game by nature is a sort of dominatrix, stomping you down into the dirt and cracking the whip at your attempts to fight back. It's brutal, frustrating, agonizing to watch as your nerves fray and senses dull, with each encounter providing a fresh boot to the teeth. Broken, battered and bruised, you look for solace, only to be greeted with a stone-cold consolation prize for your struggles. Against the crushing odds, each step becomes heavier, each mistimed strike putting you at the whims of Heaven and Hell alike. Hours pass, anger boils over, resentment turns to fascination… and the highlight of any character action game, the most brilliant of afterglows, shines clearly – the flow state: the melding of mind and body, attuned to the same frequency for a singular purpose. Free from your submission to unceasing cruelty, you take the reigns as a domineering hellion, a unholy agent of divine retribution against the legions of Heaven's army.

Unshackled from preconceived notions, Bayonetta's essence breaths uninterrupted. PlatinumGames's masterwork is informed by the inescapable interplay of sex and violence; the first glance at Bayonetta herself can tell you that. But despite the game's seemingly adolescent pandering, there burns a heart of rebellion within the work, a feminist bend buried under the suffocating weight of the social gaming sphere circa 2009. The duality of Bayonetta, as sex-positive icon of empowerment versus gross exploitation of sexuality, is ingrained into every aspect of her.

This is to say that, despite the obvious trashiness inherent to the game, the blatant fanservice and standard anime bullshit lacing the game, it's hard not to see a extreme version of myself I'd want to see: a hyper-femme confidence elemental, a perfect beauty that defines human limitation, a plain-and-simple unstoppable bad-ass. Dare I say, with every tasteless shot and embarrassing line in consideration, that Bayonetta is, in fact, transition goals?

In a way, Bayonetta represents an "ideal", a splinter of me shattered and scattered across a million separate works. But with this knowledge in mind, it's difficult not to feel slightly conflicted: after all, the character exists as an amalgamation of Hideki Kamiya's fetishes and fantasies, a woman that literally lives to please a man. For all my desires to view her as some new-age feminist idol, she is a personification of the objectification of women in gaming. I suppose it's only fair to invision her divorced from her initial context, a messy reimagining to fit her into an even messier personal image. Consider it me embracing another odd inspiration into an increasingly messy queer narrative.

The scandalous spirit of Bayonetta is, at the same time, its most beautiful and most reprehensible quality. Without it, it would stand as a husk, mechanically interesting, but without a soul to prop it up. In equal senses, it's the exact reason I recommend and shy away from suggesting the game; it represents a part of me, while also being an element I'm somewhat ashamed to admit to. Needless to say… this game feels essential. Whether it clicks with you on an individual level or not, you owe it to yourself to try it.

Unshackled from preconceived notions, Bayonetta's essence breaths uninterrupted. PlatinumGames's masterwork is informed by the inescapable interplay of sex and violence; the first glance at Bayonetta herself can tell you that. But despite the game's seemingly adolescent pandering, there burns a heart of rebellion within the work, a feminist bend buried under the suffocating weight of the social gaming sphere circa 2009. The duality of Bayonetta, as sex-positive icon of empowerment versus gross exploitation of sexuality, is ingrained into every aspect of her.

This is to say that, despite the obvious trashiness inherent to the game, the blatant fanservice and standard anime bullshit lacing the game, it's hard not to see a extreme version of myself I'd want to see: a hyper-femme confidence elemental, a perfect beauty that defines human limitation, a plain-and-simple unstoppable bad-ass. Dare I say, with every tasteless shot and embarrassing line in consideration, that Bayonetta is, in fact, transition goals?

In a way, Bayonetta represents an "ideal", a splinter of me shattered and scattered across a million separate works. But with this knowledge in mind, it's difficult not to feel slightly conflicted: after all, the character exists as an amalgamation of Hideki Kamiya's fetishes and fantasies, a woman that literally lives to please a man. For all my desires to view her as some new-age feminist idol, she is a personification of the objectification of women in gaming. I suppose it's only fair to invision her divorced from her initial context, a messy reimagining to fit her into an even messier personal image. Consider it me embracing another odd inspiration into an increasingly messy queer narrative.

The scandalous spirit of Bayonetta is, at the same time, its most beautiful and most reprehensible quality. Without it, it would stand as a husk, mechanically interesting, but without a soul to prop it up. In equal senses, it's the exact reason I recommend and shy away from suggesting the game; it represents a part of me, while also being an element I'm somewhat ashamed to admit to. Needless to say… this game feels essential. Whether it clicks with you on an individual level or not, you owe it to yourself to try it.

some of it actually really resonated with me. i like this. wish i learned about it in a way that wasn't "haha funny name". intensely personal in a way that is uncomfortable, but felt... like experiences I recall. raw emotions. actually feel fucked that all the reviews are just joke reviews by people unwilling to broach the subject, or more fairly, just unable to relate. loved this.

1996

2022

1997

Thriving off the pastiche of early morning 90s anime, somewhere between Astro Boy, Pokémon and One Piece, Mega Man Legends wears the sanguine smile of a lost decade of anime, a face recognizable to only the most jaded of despondent 20-something weebs and old-head otakus. Conceptually light, the game mostly treads the same footing as it’s inspiration: our plucky protagonists crash-land on a distant island, foil bumbling sky pirates, and unearth treasure and secrets aplenty in the name of fortune and getting back home. It’s simple, it’s clean, it’s the foundation for a generation of anime writing, but like the greatest baby anime, the concept isn’t what sells you on Mega Man Legends: It’s simply a gateway to some stellar vibes.

Driven by low-stakes and a peaceful atmosphere, the game brings to mind the feeling of waking up just in time to catch Pokémon before you run off to school, the emotions bound to that half-hour slice, the hominess of the entertainment you grow up with. Like an audio-visual security blanket, Mega Man Legends is nostalgia given form, a work built not for overshadow competition and breaking new ground, but to provide an experience that felt immediately familiar, yet uniquely new.

Even compared to its predecessors, Mega Man Legends sits in sharp contrast; as if in reaction to the lethal edge and melodrama of the Mega Man X series, a story of betrayal, loss, death, and general misery, Legends expounds boundless optimism in the face of adversity, unbreakable bravery in the face of crushing odds, and a bunch of goofy doofuses filling a cast of instantly lovable faces. If anything, the game designed to take advantage of the new technology afforded to the PlayStation feels like a much more genuine reconciliation of the tone of the original Mega Man series, while the game designed to retain the old-school fan base was deeply tinged by the style and aesthetic of gritty, grimy 90s OVAs and anime.

Talking about the mechanics in a game like this feels pointless: You are there, without question, to experience the story, meet the characters, and appreciate the world the game has developed. The gameplay itself exists as a method to feed that experience to you; while deeply dated, and reflective of the past of game design in its philosophy, it stands less as a foundational flaw of the game and more part of the overall story. In an inversion of John Carmack’s infamous quote, the gameplay is expected to be there, but it’s not important.

It’s difficult to speak uncritically about a game with such an established cultural relevance, and it’s equally difficult to find something meaningful to say. For me, Mega Man Legends is the epitome of a bygone era of anime, a touchstone on a generation of anime that inspired artists, writers and directors through the present day. It’s watching Yu-Gi-Oh as you wake up, it’s catching Digimon during a lazy Sunday. It’s emblematic of nostalgia as an idea, and how it relates to the media we approached as children, and how those tastes shape what we love and appreciate now.

Driven by low-stakes and a peaceful atmosphere, the game brings to mind the feeling of waking up just in time to catch Pokémon before you run off to school, the emotions bound to that half-hour slice, the hominess of the entertainment you grow up with. Like an audio-visual security blanket, Mega Man Legends is nostalgia given form, a work built not for overshadow competition and breaking new ground, but to provide an experience that felt immediately familiar, yet uniquely new.

Even compared to its predecessors, Mega Man Legends sits in sharp contrast; as if in reaction to the lethal edge and melodrama of the Mega Man X series, a story of betrayal, loss, death, and general misery, Legends expounds boundless optimism in the face of adversity, unbreakable bravery in the face of crushing odds, and a bunch of goofy doofuses filling a cast of instantly lovable faces. If anything, the game designed to take advantage of the new technology afforded to the PlayStation feels like a much more genuine reconciliation of the tone of the original Mega Man series, while the game designed to retain the old-school fan base was deeply tinged by the style and aesthetic of gritty, grimy 90s OVAs and anime.

Talking about the mechanics in a game like this feels pointless: You are there, without question, to experience the story, meet the characters, and appreciate the world the game has developed. The gameplay itself exists as a method to feed that experience to you; while deeply dated, and reflective of the past of game design in its philosophy, it stands less as a foundational flaw of the game and more part of the overall story. In an inversion of John Carmack’s infamous quote, the gameplay is expected to be there, but it’s not important.

It’s difficult to speak uncritically about a game with such an established cultural relevance, and it’s equally difficult to find something meaningful to say. For me, Mega Man Legends is the epitome of a bygone era of anime, a touchstone on a generation of anime that inspired artists, writers and directors through the present day. It’s watching Yu-Gi-Oh as you wake up, it’s catching Digimon during a lazy Sunday. It’s emblematic of nostalgia as an idea, and how it relates to the media we approached as children, and how those tastes shape what we love and appreciate now.

2022

2016

Closing out a decade of Dead Rising, the fourth and final entry in the series is a flickering candle, a sputtering flame compared to the galactic supernova that was its forefather. The wick burns dimly, a slow glow fading from an empty room; Dead Rising’s found-family, Capcom Vancouver, returned to ash with the ill-received launch of Dead Rising 4, leaving the neglected to quietly parish among the ruins. The black sheep rests, each prolonged second snuffing out the light, a foregone conclusion coming to fruition. From Frank, to Chuck, to Nick, all pawns in the dawn of the dead, we turn our sights to the final era of Frank West. It comes to this. The beginning and the end, Capcom’s Memento Mori of the Dead. The eternal end of Dead Rising.

Inside that decrepit tomb, sheltered from the wages of perpetuity, you lie. Tattered and ragged, the skin stretched thin over creaking bones, I’m struck with pangs of reminiscence. You’re Frank West, but not the one I know. You’re Willamette, but one from a different world. You’re "Dead Rising", but not one I recognize. Each moment with you is a recollection of better days, and for that, I have nothing but contempt for you. The mechanisms beneath have faltered, the smile has decayed, toothless and rotten, your very self torn away, stripped clean from the hollow skeleton I stare at.

But as much as I’ve been told to hate you, to despise this so-called resting place, I can’t force myself to do so. Engulfed in the soft glow of enmity, my experience with you was not moments of anger, misery, or malice. Locking eyes with the evanescent embers, my goal was clear: Acceptance, in the face of loathing. Embracing the light that was in my life, and not the shallow hollowness in front of me. And most of all, letting sleeping ghosts rest peacefully. Once, I would look upon you, a ray of cosmic brilliance piercing my retinas, a direct concentration of everything I loved and would come to love, a burning beam of sunlight. Now, the flame has died, smoke rising from an ashen stem. Surrounded by encroaching darkness, I can finally bury my memories of you, a peace deserved but long-delayed.

Minutes pass, hours, and now weeks. Every instance apart stings, a double-sided blade dividing my being; You killed the heart of a man I found myself endeared to, but would I have been endeared if not for you in the first place? You stole the essence of time from me, but would I have missed it without you showing the importance of the time I have? You gave me a universe of options and opportunity, but could I ever appreciate it after you taught me to thrive within limitations? Away from it all, I’ve come to accept that you, the creature known as Dead Rising, could never be what I need. Under the ocean sands, your body resides, a forbidden mistake upon the world's unforgiving gaze. But sitting on the shore, I will never bring myself to hate you, not as is so easily done by those near and dear to me. For your missteps, every half-cocked misfire that led me to this point, you showed me something that will stick with me until my dying breath. For that, I thank you. And with that, I need to move on.

Nostalgia’s high tide engulfs the rubble, the seafoam of loss eating into bygone shores. The waves have drowned the memories I made, but as I peer over the crystalline beaches, the deep washes over your grave. For as often as you are buried below the sand, an endless repetition of undying death, I still am drawn in by your ghost, pulled in by the beloved song of Dead Rising. But my love, desecrated as it is, can only fall victim to the same charms so many times.

You are beyond recall, buried in the abyssal plain… and for what it’s worth, I’m at peace.

Inside that decrepit tomb, sheltered from the wages of perpetuity, you lie. Tattered and ragged, the skin stretched thin over creaking bones, I’m struck with pangs of reminiscence. You’re Frank West, but not the one I know. You’re Willamette, but one from a different world. You’re "Dead Rising", but not one I recognize. Each moment with you is a recollection of better days, and for that, I have nothing but contempt for you. The mechanisms beneath have faltered, the smile has decayed, toothless and rotten, your very self torn away, stripped clean from the hollow skeleton I stare at.

But as much as I’ve been told to hate you, to despise this so-called resting place, I can’t force myself to do so. Engulfed in the soft glow of enmity, my experience with you was not moments of anger, misery, or malice. Locking eyes with the evanescent embers, my goal was clear: Acceptance, in the face of loathing. Embracing the light that was in my life, and not the shallow hollowness in front of me. And most of all, letting sleeping ghosts rest peacefully. Once, I would look upon you, a ray of cosmic brilliance piercing my retinas, a direct concentration of everything I loved and would come to love, a burning beam of sunlight. Now, the flame has died, smoke rising from an ashen stem. Surrounded by encroaching darkness, I can finally bury my memories of you, a peace deserved but long-delayed.

Minutes pass, hours, and now weeks. Every instance apart stings, a double-sided blade dividing my being; You killed the heart of a man I found myself endeared to, but would I have been endeared if not for you in the first place? You stole the essence of time from me, but would I have missed it without you showing the importance of the time I have? You gave me a universe of options and opportunity, but could I ever appreciate it after you taught me to thrive within limitations? Away from it all, I’ve come to accept that you, the creature known as Dead Rising, could never be what I need. Under the ocean sands, your body resides, a forbidden mistake upon the world's unforgiving gaze. But sitting on the shore, I will never bring myself to hate you, not as is so easily done by those near and dear to me. For your missteps, every half-cocked misfire that led me to this point, you showed me something that will stick with me until my dying breath. For that, I thank you. And with that, I need to move on.

Nostalgia’s high tide engulfs the rubble, the seafoam of loss eating into bygone shores. The waves have drowned the memories I made, but as I peer over the crystalline beaches, the deep washes over your grave. For as often as you are buried below the sand, an endless repetition of undying death, I still am drawn in by your ghost, pulled in by the beloved song of Dead Rising. But my love, desecrated as it is, can only fall victim to the same charms so many times.

You are beyond recall, buried in the abyssal plain… and for what it’s worth, I’m at peace.

2019

For want of not completely exposing my messy mental health escapades on a public review site / sort-of game blogging microcosm, I'll leave my review at me feeling some personal attachment to the story of this game. I suppose playing out the toxic and positive aspects of the inner voice, the proverbial "voice in your head", does something to personify the inherent discomfort and fear of having some indistinct audience to your life.

Of course, I'm not that player, and as much as I want to embrace the story the game wants to tell, there's really no... reason, to treat the protagonist with anything other than care. Maybe that's part of the message: Of the intrinsic disorder of negative thoughts , the uncontrollable nature of intrusive thoughts. Wish it was done through deeper prose, relying less on trite scares ingrained into the visual novel landscape.

I relate, but it doesn't really... say anything, that isn't already deeply well known to those who suffer from mental issues, or the wider landscape of "people with a normal amount of empathy". Wish there was more to it!

Of course, I'm not that player, and as much as I want to embrace the story the game wants to tell, there's really no... reason, to treat the protagonist with anything other than care. Maybe that's part of the message: Of the intrinsic disorder of negative thoughts , the uncontrollable nature of intrusive thoughts. Wish it was done through deeper prose, relying less on trite scares ingrained into the visual novel landscape.

I relate, but it doesn't really... say anything, that isn't already deeply well known to those who suffer from mental issues, or the wider landscape of "people with a normal amount of empathy". Wish there was more to it!

2001

2001

She saunters casually, pulse slow and steady, as she meanders through the decrepit halls of Hotel Banballow. The stagnant air, suffocating like a thick fog, stands as a constant reminder of the incendiary fate that befell the manor, alongside the owner’s son, one Jimmy Banballow. Silence hangs heavily through the vacant corridors, an unending moment punctuating the loss of one life and the taking of many others, as the latest victim inches closer to her demise. With Jimmy’s beloved baseball bat clutched stiffly in her palm, caked in an absurd coating of viscera, Eriko Christy makes her way to an eventual dead-end, a one-way confrontation with the man behind the slaughter, Gale Banballow, eternally vengeful over the death of his son. The sharp hiss of a blowtorch begins to pierce through the veil, a siren song signaling a violent end…

Until the tension is cut by another crash test dummy jumping you, hitting you with sidekicks and an oversized wrench, escapable with only the finest of frame-traps and side-steps. Her foe maimed and brutalized, Eriko walks away, a blank stare on her face as she speaks her one-word eulogy: “Cool!”

Illbleed is as sincere as horror gets. Beyond the high-concept of a killer amusement park with a $100 million cash prize, nothing cuts to the inherent silliness of horror like Illbleed. For context, the 90s and early 2000s were an era of introspection and reflection with horror, where metanarrative and critique became the standard through which the genre could express itself. The innate need to satirize and comment on the tropes that solidified the genre itself became a trope, a voice strained by overuse. Thus, sincerity in horror, the wink-and-smile that formed the backbone of the medium, was shattered. However, as film moved further from the side-show roots of 70s and 80s horror, other formats became the realm for celebration of the old-school mentality.

Cue none other than Illbleed. Acting as reflections on the genre’s messy past, the game is split into six episodic stages, each representing different subgenres. Ranging from straightforward slashers to old-school creature-features, each level hinges on classic haunted house scares, pushing you into stories that feel like grinning asides to the audience, less a condemnation or remorse for the source material, and more an acknowledgement and appreciation for the works that inspired it. The jokes aren’t at the expense of classic horror, but out of a sense of love. Laughing with, rather than at them, gives this game a unique viewpoint in gaming.

When I say this, I look at the trend in modern horror games to match the expectation of modern horror films. This is to say, horror games lean toward the self-serious, the unhumorous, all in the name of truly terrifying the player, breaking down the façade of safety fundamental to any indirect medium by way of intense threat and malice. While this manifest sentiment is not a direct failing of the medium or genre, it speaks to the same cynical sarcasm that poisoned the well of horror: a refusal of the genre’s funhouse beginnings, a tacit refusal of the tactless, the tasteless, and the puerile: a refusal of the past, with sights set purely on innovation, truly original thought. Through this lens, games and their depiction of horror barely breach the surface of what the genre is capable of.

Illbleed, on a mechanical level, is flawed, stilted, and representative of a generation of design that has been overwritten and forgotten. But in that same sense, what better way to reflect on the works of the past than by incorporating your medium’s flawed past into that retrospection? What can tie a game to horror’s fraught, tangled past better having remnants of the past be part of the game design itself?

It’s hard to categorize Illbleed as anything more than schlock, a heart kept pounding with the screams of B-movie scares and cheap haunted house tricks, but there’s an intrinsic originality in the energy of the B-movie, of the midnight movie and the genre film. Not only as a work honoring a legacy of horror before it, Illbleed an original exploration on the humor and excess that created the modern horror movie in the first place, which in its own right puts it in a unique place in gaming, especially within the console release scene of the mid-2000s.

As a game bound to bounce off of the majority of players for very valid reasons, it’s difficult to just unabashedly recommend Illbleed as a must-play, or some major strive in the medium of gaming, because… well, it’s not. My love for it stems from an intensely personal place, as my love for this game stems from my love of slasher films, monster flicks, the realms of the gory and the gruesome. To love Illbleed is to love horror, as broken and chaotic as it can be.

Until the tension is cut by another crash test dummy jumping you, hitting you with sidekicks and an oversized wrench, escapable with only the finest of frame-traps and side-steps. Her foe maimed and brutalized, Eriko walks away, a blank stare on her face as she speaks her one-word eulogy: “Cool!”

Illbleed is as sincere as horror gets. Beyond the high-concept of a killer amusement park with a $100 million cash prize, nothing cuts to the inherent silliness of horror like Illbleed. For context, the 90s and early 2000s were an era of introspection and reflection with horror, where metanarrative and critique became the standard through which the genre could express itself. The innate need to satirize and comment on the tropes that solidified the genre itself became a trope, a voice strained by overuse. Thus, sincerity in horror, the wink-and-smile that formed the backbone of the medium, was shattered. However, as film moved further from the side-show roots of 70s and 80s horror, other formats became the realm for celebration of the old-school mentality.

Cue none other than Illbleed. Acting as reflections on the genre’s messy past, the game is split into six episodic stages, each representing different subgenres. Ranging from straightforward slashers to old-school creature-features, each level hinges on classic haunted house scares, pushing you into stories that feel like grinning asides to the audience, less a condemnation or remorse for the source material, and more an acknowledgement and appreciation for the works that inspired it. The jokes aren’t at the expense of classic horror, but out of a sense of love. Laughing with, rather than at them, gives this game a unique viewpoint in gaming.

When I say this, I look at the trend in modern horror games to match the expectation of modern horror films. This is to say, horror games lean toward the self-serious, the unhumorous, all in the name of truly terrifying the player, breaking down the façade of safety fundamental to any indirect medium by way of intense threat and malice. While this manifest sentiment is not a direct failing of the medium or genre, it speaks to the same cynical sarcasm that poisoned the well of horror: a refusal of the genre’s funhouse beginnings, a tacit refusal of the tactless, the tasteless, and the puerile: a refusal of the past, with sights set purely on innovation, truly original thought. Through this lens, games and their depiction of horror barely breach the surface of what the genre is capable of.

Illbleed, on a mechanical level, is flawed, stilted, and representative of a generation of design that has been overwritten and forgotten. But in that same sense, what better way to reflect on the works of the past than by incorporating your medium’s flawed past into that retrospection? What can tie a game to horror’s fraught, tangled past better having remnants of the past be part of the game design itself?

It’s hard to categorize Illbleed as anything more than schlock, a heart kept pounding with the screams of B-movie scares and cheap haunted house tricks, but there’s an intrinsic originality in the energy of the B-movie, of the midnight movie and the genre film. Not only as a work honoring a legacy of horror before it, Illbleed an original exploration on the humor and excess that created the modern horror movie in the first place, which in its own right puts it in a unique place in gaming, especially within the console release scene of the mid-2000s.

As a game bound to bounce off of the majority of players for very valid reasons, it’s difficult to just unabashedly recommend Illbleed as a must-play, or some major strive in the medium of gaming, because… well, it’s not. My love for it stems from an intensely personal place, as my love for this game stems from my love of slasher films, monster flicks, the realms of the gory and the gruesome. To love Illbleed is to love horror, as broken and chaotic as it can be.

2012

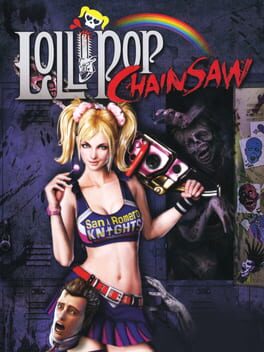

(Slight content warning: Some of the work discussed here isn’t exact safe for work, for a variety of reasons. I chose not to link to anything, but if you dig on your own… y’know. Look Out.)

There’s always a difficulty in viewing works like Lollipop Chainsaw through an analytical lens. On a surface level, the game spews out vicious bloodshed and references-disguised-as-jokes by way of a barely-legal blonde bombshell voiced by Tara Strong, hot off the presses from the seven other games she acted in that year. Cutting deeper, breaking the skin of easy T&A and lukewarm comedy, the blood of the B-movie flows freely, an exhumed exploitation expression bearing the scars of grindhouse cinema. With inspirations ranging from splatter horror and the impressively-direct sexploitation subgenre, and spearheaded by self-proclaimed punk Suda51 and Troma alumni James Gunn, Lollipop Chainsaw is, for better or worse, the same sort of gore-soaked titillation that swept through drive-in theaters and low-budget dive cinemas in the 1960s and 70s.

But, pray-tell, what makes it fit among the prestige derived from that lineage, you may ask? What aligns Lollipop Chainsaw with hallmarks of the genre, with Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! or Cannibal Holocaust? In what way is this game different from the legions of flavor-of-the-month titty games that drop from the garbage shoot that is steam, or the waves of ultraviolent mass murder simulators washing ashore from untold origins? How is it better? How is it worse?

That’s the problem; there is no real distinction. No marks of quality, no big-time writers or esteemed directors could change the fact that the “trash games” of today are, simply, an extension of the “trash cinema” of yesterday. When removed from the context of “children’s plaything” or “unique audiovisual medium”, video games take on the language and identity we ascribe to thousands of films, plays, and books. Looking at work churned out by multi-million entertainment conglomerates, you see the hallmarks of mainstream film being used as the benchmark for excellence. As an interactive mode of expression, it’s inevitable that games go beyond the realm of what is acceptable to a mainstream audience, venturing into the grimey, the messy, the extreme. After all, what is Senran Kagura if not an extrapolation of The Switchblade Sisters? What is Splatterhouse if not the logical conclusion of Hausu?

Now, I understand that this may all come off as statements dreamed up by the utterly deranged, that this could be the result of introspection and pretension too far gone to consider. Before I am soundly laughed out of the Backloggd community, consider: In the Wider Gaming Community’s push for video games to be viewed as art, isn't it also important to appreciate that which goes beyond the traditional accepted view of art? The existence of sleazy slashers and lowbrow smut doesn’t revoke the existence of time-honored masterpieces in film, in written pieces, even in the work of playwrights dating back to ancient times. As the acceptance of gaming as artwork, whatever that truly entails, dawns near, is it fair to deride the messier side of the medium as unapproachable, of being unworthy of contemplative thought? Does Lollipop Chainsaw and its ilk deserve its branding as something holding back serious discussion of gaming, or is that simply an indication of the immaturity of not only the medium, but of criticism around it?

There’s always a difficulty in viewing works like Lollipop Chainsaw through an analytical lens. On a surface level, the game spews out vicious bloodshed and references-disguised-as-jokes by way of a barely-legal blonde bombshell voiced by Tara Strong, hot off the presses from the seven other games she acted in that year. Cutting deeper, breaking the skin of easy T&A and lukewarm comedy, the blood of the B-movie flows freely, an exhumed exploitation expression bearing the scars of grindhouse cinema. With inspirations ranging from splatter horror and the impressively-direct sexploitation subgenre, and spearheaded by self-proclaimed punk Suda51 and Troma alumni James Gunn, Lollipop Chainsaw is, for better or worse, the same sort of gore-soaked titillation that swept through drive-in theaters and low-budget dive cinemas in the 1960s and 70s.

But, pray-tell, what makes it fit among the prestige derived from that lineage, you may ask? What aligns Lollipop Chainsaw with hallmarks of the genre, with Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! or Cannibal Holocaust? In what way is this game different from the legions of flavor-of-the-month titty games that drop from the garbage shoot that is steam, or the waves of ultraviolent mass murder simulators washing ashore from untold origins? How is it better? How is it worse?

That’s the problem; there is no real distinction. No marks of quality, no big-time writers or esteemed directors could change the fact that the “trash games” of today are, simply, an extension of the “trash cinema” of yesterday. When removed from the context of “children’s plaything” or “unique audiovisual medium”, video games take on the language and identity we ascribe to thousands of films, plays, and books. Looking at work churned out by multi-million entertainment conglomerates, you see the hallmarks of mainstream film being used as the benchmark for excellence. As an interactive mode of expression, it’s inevitable that games go beyond the realm of what is acceptable to a mainstream audience, venturing into the grimey, the messy, the extreme. After all, what is Senran Kagura if not an extrapolation of The Switchblade Sisters? What is Splatterhouse if not the logical conclusion of Hausu?

Now, I understand that this may all come off as statements dreamed up by the utterly deranged, that this could be the result of introspection and pretension too far gone to consider. Before I am soundly laughed out of the Backloggd community, consider: In the Wider Gaming Community’s push for video games to be viewed as art, isn't it also important to appreciate that which goes beyond the traditional accepted view of art? The existence of sleazy slashers and lowbrow smut doesn’t revoke the existence of time-honored masterpieces in film, in written pieces, even in the work of playwrights dating back to ancient times. As the acceptance of gaming as artwork, whatever that truly entails, dawns near, is it fair to deride the messier side of the medium as unapproachable, of being unworthy of contemplative thought? Does Lollipop Chainsaw and its ilk deserve its branding as something holding back serious discussion of gaming, or is that simply an indication of the immaturity of not only the medium, but of criticism around it?