kaijuu

43 Reviews liked by kaijuu

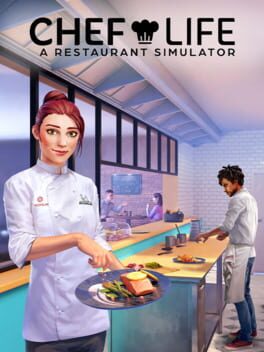

I was NOT expecting this level of commitment/compromise when I walked in for my first culinary lesson, nor when I started working in restaurants, nor when I downloaded this game (that is grotesquely similar to how a real restaurant works) just to see what it is about. It is funny that these three experiences sucked me in so abruptly that I found myself obliged to hurry to get things done and learn everything as fast as I could.

The kitchen experience blows me away, always will, and when I say kitchen I don’t mean only the cooking itself, I mean the physical kitchen, this white, bright, full of chemistry and mysterious micro explosions, hyper sanitized and simultaneously desperately messy space - the underlying philosophy of the whole place is to physically contain any type of chaos, be it contamination, disorganization, fire (literally and figuratively), so the layout design of every restaurant kitchen tries to emulate this accident-proof room where everything has a correct place, position, moment, which backfires in being a tense, explosive, often careless experience. This dynamic is cleverly translated in chronometers and queue lines, step by step, conciliating tasks - a pretty amazing job imo.

And of course, the cooking, maybe as a spiritual activity, as in connecting with ancestors and humanity through the smells and textures and the (many) feelings that I feel for food, maybe as a profound cultural deep dive, understanding the many ways to build even the most simple and classic recipes - and why their traditional blueprint work so well in the first place - maybe as an art form even, an expression from the soul of the deep abstract desires of not survival but living, and also an obvious scientific exploration, because it is awesome and scary how far we got from picking fruits from a tree to cultivating yeast and then having the resources/the control over the land/time to prepare enormous feasts for many people to enjoy together abundantly, to baking pink biscuits and using liquid nitrogen to build beautiful shapes of taste. And the restaurant aspect of it is a complex manifestation of the crave for oneness, the want to be together, to provide, to share, and to love, which is: though destructive and passionate and sometimes too much of a proud control freak, it only wants you well served and happily digesting.

Chef Life is careful with every detail of this bittersweet, humane infatuation.

It also has a wholesome approach, offering the challenge to rush and memorize every recipe and focus on the mise en place to get the michelin star (30+ hours in and still didn’t) or if you want to play it laid back, unpressured, creatively, it is also an option. I was impressed with these accessibility options, makes the whole experience so beautifully welcoming.

The kitchen experience blows me away, always will, and when I say kitchen I don’t mean only the cooking itself, I mean the physical kitchen, this white, bright, full of chemistry and mysterious micro explosions, hyper sanitized and simultaneously desperately messy space - the underlying philosophy of the whole place is to physically contain any type of chaos, be it contamination, disorganization, fire (literally and figuratively), so the layout design of every restaurant kitchen tries to emulate this accident-proof room where everything has a correct place, position, moment, which backfires in being a tense, explosive, often careless experience. This dynamic is cleverly translated in chronometers and queue lines, step by step, conciliating tasks - a pretty amazing job imo.

And of course, the cooking, maybe as a spiritual activity, as in connecting with ancestors and humanity through the smells and textures and the (many) feelings that I feel for food, maybe as a profound cultural deep dive, understanding the many ways to build even the most simple and classic recipes - and why their traditional blueprint work so well in the first place - maybe as an art form even, an expression from the soul of the deep abstract desires of not survival but living, and also an obvious scientific exploration, because it is awesome and scary how far we got from picking fruits from a tree to cultivating yeast and then having the resources/the control over the land/time to prepare enormous feasts for many people to enjoy together abundantly, to baking pink biscuits and using liquid nitrogen to build beautiful shapes of taste. And the restaurant aspect of it is a complex manifestation of the crave for oneness, the want to be together, to provide, to share, and to love, which is: though destructive and passionate and sometimes too much of a proud control freak, it only wants you well served and happily digesting.

Chef Life is careful with every detail of this bittersweet, humane infatuation.

It also has a wholesome approach, offering the challenge to rush and memorize every recipe and focus on the mise en place to get the michelin star (30+ hours in and still didn’t) or if you want to play it laid back, unpressured, creatively, it is also an option. I was impressed with these accessibility options, makes the whole experience so beautifully welcoming.

NieR Re[in]carnation

2021

thesis: yoko taro is often listed among the foremost auteurs of the medium but the reality is his strengths lie in a kind of prototypical 'video game' method of work, borne out of necessity, that prioritizes collaboration between a consistent set of screenwriters, an unorthodox style of design targeting emotional resonance, and a plethora of unique flourishes specifically aimed at facilitating the empathy, immersion, and connection of its players (researching drakengard 1s development makes this especially apparent - it's arguably not even a yoko taro game in the usually defined sense of the term). his works, when in production, are thwarted frequently by compromise, limitation, and sacrifice - stumbling blocks, all in service of eventually reflecting a well-trodden title which charms on the virtues of its rustic artistry. wear and tear and a heart of gold. this style of development, marked by haste and experimentation and fueled by pure zeal and love for the craft, perhaps reveals why the pillars of video games, the codified monomythic genres and the primordial archetypes and the frequent allusions to popular work, so often impress themselves upon yoko taro games, and why so often his work succeeds in connecting to people where other talent may struggle. the video game of it all, if you will. incidentally, this collaborative style allows for a large breadth of potential interpretation and analysis afforded towards his work, and ive long maintained that a YT game is at its most interesting when it's not about what he intended for it to be about. did the tragedies in nier gestalt sometimes fall flat for you? me too! thankfully that's not what the game is about, at least not to me. in sum: the work of many, each willing and able to leave a fingerprint on the mosaic of development, enriches the product in the long-run, creating a full-bodied textured work of art and contributing immensely to the humanity at the core of these games. if any given chord strikes you as dull, a separate melody will enchant you - that's the nature of YT's games. they're artisan because of what they value and because of how they achieve their mission statement, and especially because of their passion, always demonstrated by the little details in these games. passion will always reveal itself, but so too will a dearth of passion reveal itself.

proof: nier re[in]carnation

if these games worked because of a certain je ne sais quois shared by the collaborative nature of a team in a trying work environment, i don't think my prospective next project would be a game in an exploitative genre where a new team of writers handled an endless barrage of one-note vignettes while YT sat back, nodded halfheartedly at his desk, and tried to string every vignette together using an overarching plot catering to obsessive drakennier fans. just my two cents

proof: nier re[in]carnation

if these games worked because of a certain je ne sais quois shared by the collaborative nature of a team in a trying work environment, i don't think my prospective next project would be a game in an exploitative genre where a new team of writers handled an endless barrage of one-note vignettes while YT sat back, nodded halfheartedly at his desk, and tried to string every vignette together using an overarching plot catering to obsessive drakennier fans. just my two cents

Unlimited SaGa

2002

é claro que depois de cinquenta anos de treino hoje a gente considera videogame algo "intuitivo", mas não é uma prática psico ou fisiologicamente natural. minha mãe sofria muito quando tinha que apertar pra frente e o botão de pulo ao mesmo quando eu tentava fazer ela jogar donkey kong country 3, e isso não quer dizer que ela era incapaz ou que o jogo "não ensinava direito", mas sim que ela não havia praticado tanto quanto eu. a graça de unlimited saga é que ele é impraticável, inacostumável, mesmo se você gostar de videogame, gostar de rpg, gostar de jogo por turno, gostar de jogo de tabuleiro ou gostar de outros saga.

não dá pra dizer que ele foi feito pra alguém. intuitivamente ninguém vai orbitá-lo. nem mesmo os criadores! foi um esforço tornar ele tão obtuso quanto é, uma filosofia de atrito, documentada. não acho nem que é um jogo que o kawazu fez pra si mesmo. entretanto, também não é um exercício de hostilidade: o jogo é super agradável esteticamente. ele te chama e te acaricia, te dá a tal da dopamina em todos os momentos de aposta, se revela, mas sua profundidade é tamanha que sempre vai faltar algo para você conseguir entender completamente. ele te manipula em seus mistérios, no que deixa de revelar, nos seus resultados imprevisíveis, nas maldadezinhas ocasionais e nos presentes inesperados.

é legal também que a única cena super animada e elaborada seja no mesmo lugar para todos os personagens — eu sempre ficava ansioso pra chegar em regina leone pra ver como iam mostrar o festival dessa vez. serve como o núcleo de familiaridade entre todas as histórias, visto que o contexto sinestésico delas também varia muito. você aprende bastante cada vez que completa uma, mas nunca o suficiente pra próxima ser fácil ou só uma lapidação de conceitos.

todos os momentos de unlimited saga são como jogar videogame pela primeira vez. eu nem lembro como foi essa sensação de verdade porque na minha cabeça eu já nasci usando uma meia do Sonic, mas agora consigo sentir esse ataque meio esquizo aos sentidos que é apertar um botão e sentir que tenho que lutar com minha própria mente com o qual já tinha me acostumado como se fosse novo. sensação de projeção astral em outro mundo onde não existe nenhuma convenção artística e tudo é cognitivamente violento. não gostaria de morar lá, mas visitar é sempre uma diversão.

não dá pra dizer que ele foi feito pra alguém. intuitivamente ninguém vai orbitá-lo. nem mesmo os criadores! foi um esforço tornar ele tão obtuso quanto é, uma filosofia de atrito, documentada. não acho nem que é um jogo que o kawazu fez pra si mesmo. entretanto, também não é um exercício de hostilidade: o jogo é super agradável esteticamente. ele te chama e te acaricia, te dá a tal da dopamina em todos os momentos de aposta, se revela, mas sua profundidade é tamanha que sempre vai faltar algo para você conseguir entender completamente. ele te manipula em seus mistérios, no que deixa de revelar, nos seus resultados imprevisíveis, nas maldadezinhas ocasionais e nos presentes inesperados.

é legal também que a única cena super animada e elaborada seja no mesmo lugar para todos os personagens — eu sempre ficava ansioso pra chegar em regina leone pra ver como iam mostrar o festival dessa vez. serve como o núcleo de familiaridade entre todas as histórias, visto que o contexto sinestésico delas também varia muito. você aprende bastante cada vez que completa uma, mas nunca o suficiente pra próxima ser fácil ou só uma lapidação de conceitos.

todos os momentos de unlimited saga são como jogar videogame pela primeira vez. eu nem lembro como foi essa sensação de verdade porque na minha cabeça eu já nasci usando uma meia do Sonic, mas agora consigo sentir esse ataque meio esquizo aos sentidos que é apertar um botão e sentir que tenho que lutar com minha própria mente com o qual já tinha me acostumado como se fosse novo. sensação de projeção astral em outro mundo onde não existe nenhuma convenção artística e tudo é cognitivamente violento. não gostaria de morar lá, mas visitar é sempre uma diversão.

recentemente eu assisti todos os missão impossível e percebi que no meio da série a coisa se torna mítica. o ethan hunt alcança um ar meio divino — não é mais surpreendente que ele esteja três passos à frente de todos, que ele vai conseguir carimbar a missão como possível. a tensão deixa de ser "será que ele consegue?" e passa a ser "como ele vai conseguir dessa vez?". começa a se tornar um gênero literário hermético por si só quando a história cria um cânone tão grande que suas referências passam a ser essa própria história escrita por outros nomes, em outras épocas e portanto com outras mensagens. o império pós-materialista conseguiu tornar o nome (de alguém, de algo) tão sagrado que ele guarda uma carga identitária que representa um universo por si só com sua própria ontologia artificial, palavra que também carrega cada vez menos peso negativo em uma dinâmica de tulpa que permite buscar isso como desejável mesmo assim.

a narrativa da identidade secreta não trata tanto assim do que os outros fazem pra te desmascarar e sim das conflitos internos de negar todas as suas conquistas que ocorreram até aqui; é uma briga de ego: o ego jovem da identidade nova e o ego velho da antiga. o ethan hunt passou sete filmes em paz porque ele é orgulhoso de seus feitos em todas as dimensões de sua existência, ele aceita a deificação, se banha nos sacrifícios que lhe oferecem, entende que o mundo inteiro é missão impossível; o kiryu, por outro lado, tem uma consciência meio além-jogo: todos os personagens de like a dragon existem como se like a dragon fosse tudo o que importasse no universo, mas ele não. ele tenta escapar dessa ficção, tocar em problemas reais, ter prazeres reais, fugir da reencarnação do autor, mas também sabe que se fizer isso todos os seus feitos anteriores terão sido em vão e todas as memórias vão se esvair. tudo o que ele tem agora são memórias. ele é quem teria que se sacrificar para um mundo que vai ter que, por obrigação, esquecer que ele existe.

um personagem conseguiria decidir isso bem facilmente caso fosse um aspecto importante Temático de uma História, mas quem disse que ele é um personagem?

a narrativa da identidade secreta não trata tanto assim do que os outros fazem pra te desmascarar e sim das conflitos internos de negar todas as suas conquistas que ocorreram até aqui; é uma briga de ego: o ego jovem da identidade nova e o ego velho da antiga. o ethan hunt passou sete filmes em paz porque ele é orgulhoso de seus feitos em todas as dimensões de sua existência, ele aceita a deificação, se banha nos sacrifícios que lhe oferecem, entende que o mundo inteiro é missão impossível; o kiryu, por outro lado, tem uma consciência meio além-jogo: todos os personagens de like a dragon existem como se like a dragon fosse tudo o que importasse no universo, mas ele não. ele tenta escapar dessa ficção, tocar em problemas reais, ter prazeres reais, fugir da reencarnação do autor, mas também sabe que se fizer isso todos os seus feitos anteriores terão sido em vão e todas as memórias vão se esvair. tudo o que ele tem agora são memórias. ele é quem teria que se sacrificar para um mundo que vai ter que, por obrigação, esquecer que ele existe.

um personagem conseguiria decidir isso bem facilmente caso fosse um aspecto importante Temático de uma História, mas quem disse que ele é um personagem?

Super Mario 64

1996

this game is super cool. it's a high-grade experiment that barely cares about the (already not that established) Mario tropes in exchange for nonsense tiny playgrounds that have more ideas than they have "levels" inside them. i think that's cool. it barely feels like you're playing a videogame sometimes. the floating pieces of land that you walk on are there almost entirely to take advantage of a piece of Mario's movement options, so they actually feel like those 2D Mario levels where every single thing is there in the name of the core game. but i unfortunately kinda hate that part.

i've never been a fan of nintendo's utilitarian approach to design. it just means that areas must be in some way useful more than they are actual places. in 64 this means that you're forced to care about Mario's (conceptually cool) moveset at every opportunity. i can't even enjoy my abstract nothinglands in peace without having to engage with some random setpiece to get a star.

it's the structure as well… yuno.. i'm not one to usually care about intricate challenges when a game cares about it more than anything. even considering how loose some star objectives are, they're still filled with specific little challenges that completely ruin any sense of hanging out i could've had. yeah, i also really dislike the way almost all stars kick you out of the levels. they sometimes linearly change the level to different versions of themselves that make other stars possible and some others impossible, but sometimes that just makes the levels way too bite-sized to make an impact. like, i have to get at least 70 stars in this thing, so i have no time to keep playing around because that shit takes time to do. i get a similar feeling when i'm done with 4 worlds in 2D Mario games and i know that i still gotta make my way through another 4 worlds. i'm already dreading to do the rest before i'm even there.

when you get used to a level's flow in Mario 64, it gets a little better - but then you gotta consciously go through that all over again and see some new tiny setpieces in another level. and it's gonna really suck when you realize that you can only get all the red coins (of which you already spent some time looking for) when the level changes to another star and a path to that last one opens up.

but it's such a magical game with magical lands… these understated little boxes of characters and structures made tangible only by Mario's presence are a thing to behold. the level Tall, Tall Mountain, for example, is just this huge chunk of a mountain that you gotta climb multiple times to get different stars in different situations. it feels monumental because it's one of the few levels that takes the game's trend toward up/downhill climbing to the foreground of the play. in this level specifically, stopping to smell the roses feels positively uncanny because, since everything is there for a mechanical purpose, it loses itself in the absence of interaction. that's kinda awesome but it makes my head hurt a little.

it irks me because i genuinely enjoy the landscapes in here. they're the extreme version of the visually agnostic Mario levels that feel completely alien because of how random and generic their assets are. by setting the levels up as these random paintings that you stumble onto and not holding on to even some basic staples like the turtle guys and pipes, they made something that feels really uncanny.

i don't really get how people frame some games like Majora's Mask as being "mysterious" when they feature some really charming and normal-ass writing, full-on cutscenes, and NPCs with schedules walking around the world. it feels way more deliberate than the surprising nothings that Mario 64 gives players. there's a vague sense that Bowser took over Peach's Castle but absolutely nothing that contextualizes the bonkers structure. for me that's what makes it interesting! it just really loses me when those cool aspects are stuck with nintendo's approach to games.

Mario 64 is stuck in an impossible equation in my head bc it's at once the coolest game by nintendo that i've touched because it's made by them and also a game that i dislike playing because it still tries to follow their design pillars so much. goddamnit now i wanna play more nintendo games to satisfy my curiosity. please help me

i've never been a fan of nintendo's utilitarian approach to design. it just means that areas must be in some way useful more than they are actual places. in 64 this means that you're forced to care about Mario's (conceptually cool) moveset at every opportunity. i can't even enjoy my abstract nothinglands in peace without having to engage with some random setpiece to get a star.

it's the structure as well… yuno.. i'm not one to usually care about intricate challenges when a game cares about it more than anything. even considering how loose some star objectives are, they're still filled with specific little challenges that completely ruin any sense of hanging out i could've had. yeah, i also really dislike the way almost all stars kick you out of the levels. they sometimes linearly change the level to different versions of themselves that make other stars possible and some others impossible, but sometimes that just makes the levels way too bite-sized to make an impact. like, i have to get at least 70 stars in this thing, so i have no time to keep playing around because that shit takes time to do. i get a similar feeling when i'm done with 4 worlds in 2D Mario games and i know that i still gotta make my way through another 4 worlds. i'm already dreading to do the rest before i'm even there.

when you get used to a level's flow in Mario 64, it gets a little better - but then you gotta consciously go through that all over again and see some new tiny setpieces in another level. and it's gonna really suck when you realize that you can only get all the red coins (of which you already spent some time looking for) when the level changes to another star and a path to that last one opens up.

but it's such a magical game with magical lands… these understated little boxes of characters and structures made tangible only by Mario's presence are a thing to behold. the level Tall, Tall Mountain, for example, is just this huge chunk of a mountain that you gotta climb multiple times to get different stars in different situations. it feels monumental because it's one of the few levels that takes the game's trend toward up/downhill climbing to the foreground of the play. in this level specifically, stopping to smell the roses feels positively uncanny because, since everything is there for a mechanical purpose, it loses itself in the absence of interaction. that's kinda awesome but it makes my head hurt a little.

it irks me because i genuinely enjoy the landscapes in here. they're the extreme version of the visually agnostic Mario levels that feel completely alien because of how random and generic their assets are. by setting the levels up as these random paintings that you stumble onto and not holding on to even some basic staples like the turtle guys and pipes, they made something that feels really uncanny.

i don't really get how people frame some games like Majora's Mask as being "mysterious" when they feature some really charming and normal-ass writing, full-on cutscenes, and NPCs with schedules walking around the world. it feels way more deliberate than the surprising nothings that Mario 64 gives players. there's a vague sense that Bowser took over Peach's Castle but absolutely nothing that contextualizes the bonkers structure. for me that's what makes it interesting! it just really loses me when those cool aspects are stuck with nintendo's approach to games.

Mario 64 is stuck in an impossible equation in my head bc it's at once the coolest game by nintendo that i've touched because it's made by them and also a game that i dislike playing because it still tries to follow their design pillars so much. goddamnit now i wanna play more nintendo games to satisfy my curiosity. please help me

Koudelka

1999

Re:Kinder

2010

when i'm an adult i hope to be a kinder one.

sobre trauma geracional e a dificuldade não só/necessariamente de se conectar, mas de procurar empatia, procurar quem entenda e quem ajude. talvez a única maneira de romper com o rito seja dar um fim completo ao último na linhagem da maldição, mas a bondade prevalece sob a angústia e praticá-la, mesmo ao ver o pior reflexo de nós mesmos em outrem, é a chave para tornarmos pessoas melhores.

outro banger do parun. rip.

sobre trauma geracional e a dificuldade não só/necessariamente de se conectar, mas de procurar empatia, procurar quem entenda e quem ajude. talvez a única maneira de romper com o rito seja dar um fim completo ao último na linhagem da maldição, mas a bondade prevalece sob a angústia e praticá-la, mesmo ao ver o pior reflexo de nós mesmos em outrem, é a chave para tornarmos pessoas melhores.

outro banger do parun. rip.

Mirror's Edge

2008

Pagan: Autogeny

2019

Car Companion

One aspect that my own discipline on how I go about reflecting on games on here evades is the fact that I'm kind of a moron. As I eluded mildly in my last post, Minimalist, my relationship to my memories and recall is at best mildly amusing, imitating a real 'whose on first' style of trivia prompting from other people. At its worst though, it feels like early onset dementia. For instance earlier today, somebody liked my post on Magic Vigilante this fantastic horizontal shmup that I poured a strong appraisal in. I don't remember writing this, and I almost don't remember playing the game. If you had asked me 'what did you think of Magic Vigilante' 2 days after I played the game, I would tell you 'what? what are you talking about?'. I do like it now that I remember it, I do want to play it again sometime soon, but I didn't recall it at all until that happened. It's possible part of that is due to the fact there's no point in a SHMUP where you can sit and stare at scene and let it imprint. The sequences of what you see on screen in a SHMUP are by design always moving. There's a terminal rush going on that never slows down. This explains certainly why I can remember what the shop looks like in Oblivion (dusty, some barrels around, croaky music, potion flasks littered around everywhere, a soothing tannish brown plastered on all the objects) yet not remember so well a SHMUP, but this explanation is just that: an explanation. At the end of the day my memory is still painfully jagged and sudden. It's a ball of worms, not an epiphany. This is the norm.

I don't really want to continue endlessly the wistfulness about myself here, I think it can start this slightly obnoxious descent into a panicky attitude about life. It can cause readers to want to bow out because you're no longer focused on the experiences of the game but instead yourself. I don't want to come on here and act like a David Foster Wallace short story on everyone's timeline by any means. So, the point of noting this at all is simply to say that when some of us joke we don't remember what we even had for breakfast yesterday, that's not a joke, we really mean it.

Contrast that with the work of the Pagan series and some of my initial insecurity about intelligence and memory start to make sense. Many other people mention that Pagan: Autogeny leaves the vignette formula of the previous 2 games, and clearly follows up on building a more ambitious world that those 2 games set out. Lost niche MMOs to war, girls that may no longer exist, tarot cards, etc. You're clearly meant to be in a hostile world of knowledge you're behind on. But some more behind than others. The first title, Pagan: Technopolis is stated to be good but constrained in comparison to how 'ambitious' this title is. I disagree. Before you even download the game you're hit with a James Joyce quote, you know the modernist icon of synaptic memory. I've read some Joyce, particularly A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man which in many ways may be my favorite book, but the thing is that's 19 year old Joyce, one where there's some references to a bygone past but still playful within a limit you can understand. The references aren't overwhelming yet. She quotes from a short story collection Dubliners, in which symbolic objects begin to take on a multiplicity of meaning to such an extent it feels intimidating. I've been a 'fraudulant fan' of Joyce for a good while but the reality is I never could get past the first chapter in any of his other books. I just liked the prose.

Opening the first game in your trilogy with a Joyce quote rings these very specific alarm bells to a player in the know: Pay attention! The 'small scope' of that game, duely populated as it is, makes up plenty in its evocative density. A nuclear processing plant that's just an entire section of town. A weird fox cult. A player piano ringing out in particular a classical tune I straight up cant remember (god save me for this, I hummed it drunk once in a moment of pure suffering about 5 months ago now, at my lowest, and yet I can't remember the name). Finally you're building the statue of Venus. Goddess of love. I don't know, its all very 'considered' in my view. Each symbol is trying to evoke something in reference to everything else. There's a sense of relational distance going on that is surprisingly rare for the medium. I'm behind on my mythological history though, so its all lost on me. Point is that Autogeny is not where it first gets symbolically esoteric, it's just a slightly larger version of the same contemplation.

By this game the textuality of it. In the texture of the world had set in, this game series was clever and mysterious. I was having trouble keeping up so I asked a friend to help me out. @BloodMachine. Very helpful she was, though consternated me rightly for feeling lost and helpless through the world. This was over half a year ago now, but it feels like it happened half a decade ago honestly. I beat one of the endings, and a mystical angel beamed down and broke the world. That's not the real ending, you have to go back in there and do something else. So I did, I tried to.

Then it happened. The dreadful memory of a childhood wasted.

I found what I think is a 'bug'. In Pagan: Autogeny one way in which you can fast travel is via a car. Which takes you there automatically. You can look around in the front seat as its railroads you back and forth between that destination point. Somehow the car sequence looped, and just waited around for it to stop. It never did, so I soaked in it, and lay down for a bit with it running. The soothing reverberation and chaotic anxiety of being trapped in a vehicle outside your modus of control. I was transported back to the misery of my childhood, in a miserable professorial little gender I would later denounce...

My family spent years in my youth traveling by car. Hundreds upon thousands of hours spent in this vehicle. I would always try to read, get sickly and lie down. It was boring but soothing in a bleak way. Many peoples childhoods are made up of playground antics, or daycare entertainment. They reflect fondly on how they spent years of their life like this. Mine was spent listening to shitty rock music, on the highway, quietly closing my eyes or imagining some creature a friend chasing me leaping from tree to tree inspired by the energetic scenes in Code Lyoko...my favourite show as a child which I remember shit all about now. My isolated childhood, a majority car. It came back to me. The alienness of it. No wonder I have such a faulty relationship to memory when burbling down american roads in transit is the highlight of my childhood. Keeping myself entertained through the mild car sickness by doing mental math puzzles at 5. Doing sudokus at 10. Daydreaming at 14. Thinking about anime at 19. Arrested asphalt development.

I'm not sure I will ever understand what the Pagan games are trying to tell me. But the sound effects work here in this way of 'uncovering'. When you leave one area into another there's a loud door slam noise. You swear you've heard it somewhere before. It's all satisfying in this way. You swear you've fought this frog boss somewhere before. A game that feels like a representation of something lost. In choice moments it comes into your vision and then goes vague again. You walk at the perfect speed, its all rightly woozy. This is life, ambiguous and unsatisfying in its complexity, and all you can cling onto is these weird noises that remind you of your childhood. Devs might find this relationship to their work cantankerous and anti intellectual. To me though, the sound design is the alpha and omega to this whole resonance. Trap a player in a room and perform the right sounds at them, and see what happens.

The worlds, the noises they make when you interact in certain ways. Sound design is the 'prose' of videogames. The gameplay don't have to be 'perfect'. You don't have to find the 'ending' or 'get it'. Its just there, its just those noises and that world, the complexity of references only get you so far. When all is done, for me at least, its how it sounds that really matters, and this, for me, one of the best sounding worlds out there.

One aspect that my own discipline on how I go about reflecting on games on here evades is the fact that I'm kind of a moron. As I eluded mildly in my last post, Minimalist, my relationship to my memories and recall is at best mildly amusing, imitating a real 'whose on first' style of trivia prompting from other people. At its worst though, it feels like early onset dementia. For instance earlier today, somebody liked my post on Magic Vigilante this fantastic horizontal shmup that I poured a strong appraisal in. I don't remember writing this, and I almost don't remember playing the game. If you had asked me 'what did you think of Magic Vigilante' 2 days after I played the game, I would tell you 'what? what are you talking about?'. I do like it now that I remember it, I do want to play it again sometime soon, but I didn't recall it at all until that happened. It's possible part of that is due to the fact there's no point in a SHMUP where you can sit and stare at scene and let it imprint. The sequences of what you see on screen in a SHMUP are by design always moving. There's a terminal rush going on that never slows down. This explains certainly why I can remember what the shop looks like in Oblivion (dusty, some barrels around, croaky music, potion flasks littered around everywhere, a soothing tannish brown plastered on all the objects) yet not remember so well a SHMUP, but this explanation is just that: an explanation. At the end of the day my memory is still painfully jagged and sudden. It's a ball of worms, not an epiphany. This is the norm.

I don't really want to continue endlessly the wistfulness about myself here, I think it can start this slightly obnoxious descent into a panicky attitude about life. It can cause readers to want to bow out because you're no longer focused on the experiences of the game but instead yourself. I don't want to come on here and act like a David Foster Wallace short story on everyone's timeline by any means. So, the point of noting this at all is simply to say that when some of us joke we don't remember what we even had for breakfast yesterday, that's not a joke, we really mean it.

Contrast that with the work of the Pagan series and some of my initial insecurity about intelligence and memory start to make sense. Many other people mention that Pagan: Autogeny leaves the vignette formula of the previous 2 games, and clearly follows up on building a more ambitious world that those 2 games set out. Lost niche MMOs to war, girls that may no longer exist, tarot cards, etc. You're clearly meant to be in a hostile world of knowledge you're behind on. But some more behind than others. The first title, Pagan: Technopolis is stated to be good but constrained in comparison to how 'ambitious' this title is. I disagree. Before you even download the game you're hit with a James Joyce quote, you know the modernist icon of synaptic memory. I've read some Joyce, particularly A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man which in many ways may be my favorite book, but the thing is that's 19 year old Joyce, one where there's some references to a bygone past but still playful within a limit you can understand. The references aren't overwhelming yet. She quotes from a short story collection Dubliners, in which symbolic objects begin to take on a multiplicity of meaning to such an extent it feels intimidating. I've been a 'fraudulant fan' of Joyce for a good while but the reality is I never could get past the first chapter in any of his other books. I just liked the prose.

Opening the first game in your trilogy with a Joyce quote rings these very specific alarm bells to a player in the know: Pay attention! The 'small scope' of that game, duely populated as it is, makes up plenty in its evocative density. A nuclear processing plant that's just an entire section of town. A weird fox cult. A player piano ringing out in particular a classical tune I straight up cant remember (god save me for this, I hummed it drunk once in a moment of pure suffering about 5 months ago now, at my lowest, and yet I can't remember the name). Finally you're building the statue of Venus. Goddess of love. I don't know, its all very 'considered' in my view. Each symbol is trying to evoke something in reference to everything else. There's a sense of relational distance going on that is surprisingly rare for the medium. I'm behind on my mythological history though, so its all lost on me. Point is that Autogeny is not where it first gets symbolically esoteric, it's just a slightly larger version of the same contemplation.

By this game the textuality of it. In the texture of the world had set in, this game series was clever and mysterious. I was having trouble keeping up so I asked a friend to help me out. @BloodMachine. Very helpful she was, though consternated me rightly for feeling lost and helpless through the world. This was over half a year ago now, but it feels like it happened half a decade ago honestly. I beat one of the endings, and a mystical angel beamed down and broke the world. That's not the real ending, you have to go back in there and do something else. So I did, I tried to.

Then it happened. The dreadful memory of a childhood wasted.

I found what I think is a 'bug'. In Pagan: Autogeny one way in which you can fast travel is via a car. Which takes you there automatically. You can look around in the front seat as its railroads you back and forth between that destination point. Somehow the car sequence looped, and just waited around for it to stop. It never did, so I soaked in it, and lay down for a bit with it running. The soothing reverberation and chaotic anxiety of being trapped in a vehicle outside your modus of control. I was transported back to the misery of my childhood, in a miserable professorial little gender I would later denounce...

My family spent years in my youth traveling by car. Hundreds upon thousands of hours spent in this vehicle. I would always try to read, get sickly and lie down. It was boring but soothing in a bleak way. Many peoples childhoods are made up of playground antics, or daycare entertainment. They reflect fondly on how they spent years of their life like this. Mine was spent listening to shitty rock music, on the highway, quietly closing my eyes or imagining some creature a friend chasing me leaping from tree to tree inspired by the energetic scenes in Code Lyoko...my favourite show as a child which I remember shit all about now. My isolated childhood, a majority car. It came back to me. The alienness of it. No wonder I have such a faulty relationship to memory when burbling down american roads in transit is the highlight of my childhood. Keeping myself entertained through the mild car sickness by doing mental math puzzles at 5. Doing sudokus at 10. Daydreaming at 14. Thinking about anime at 19. Arrested asphalt development.

I'm not sure I will ever understand what the Pagan games are trying to tell me. But the sound effects work here in this way of 'uncovering'. When you leave one area into another there's a loud door slam noise. You swear you've heard it somewhere before. It's all satisfying in this way. You swear you've fought this frog boss somewhere before. A game that feels like a representation of something lost. In choice moments it comes into your vision and then goes vague again. You walk at the perfect speed, its all rightly woozy. This is life, ambiguous and unsatisfying in its complexity, and all you can cling onto is these weird noises that remind you of your childhood. Devs might find this relationship to their work cantankerous and anti intellectual. To me though, the sound design is the alpha and omega to this whole resonance. Trap a player in a room and perform the right sounds at them, and see what happens.

The worlds, the noises they make when you interact in certain ways. Sound design is the 'prose' of videogames. The gameplay don't have to be 'perfect'. You don't have to find the 'ending' or 'get it'. Its just there, its just those noises and that world, the complexity of references only get you so far. When all is done, for me at least, its how it sounds that really matters, and this, for me, one of the best sounding worlds out there.

Pagan: Technopolis

2018

se a história das pessoas que passaram a sonhar em preto e branco depois da invenção da televisão for verdade, como será que a gente sonhava antes de passarem a usar sonhos como artifícios narrativos? não dava pra representar um sonho antes deles serem explorados massivamente através de dispositivos midiáticos porque todo mundo tinha uma mente, história e sinapses peculiares o bastante pros sonhos serem demonstrações exclusivas. todo sonho era diferente porque todo mundo era diferente. os símbolos identificáveis para a criação de dicionários oníricos sempre foram muito mais hermenêuticos do que observáveis por razões claras.

a tecnologia e a documentação de sonhos cria uma nuvem metafísica de como sonhos Devem Ser, e portanto todos os sonhos são assim. o nosso cérebro funciona como uma rede neural artificial, buscando espaços similares e familiares a arcos narrativos prontos e mudando os personagens e cores (de vez em quando!) para conseguirmos ler alguma coisa depois. a maneira que o mundo dos sonhos tinha de se preservar era ser esquecido imediatamente pois assim sua força de divinação se concretizava: apenas uma sugestão, nunca uma ordem. hoje a gente anota o sonho em qualquer aplicativo que vai nos dar centenas de estatísticas e interpretações se baseando em folclore (a wiki informal) e dados.

a tecnologia (não só a parte de análise estatística, a escrita por si só também é tecnologia) moldou nossos sonhos individualmente e coletivamente, mas a tecnologia só é influenciada individualmente de volta. de quem são seus sonhos?

a tecnologia e a documentação de sonhos cria uma nuvem metafísica de como sonhos Devem Ser, e portanto todos os sonhos são assim. o nosso cérebro funciona como uma rede neural artificial, buscando espaços similares e familiares a arcos narrativos prontos e mudando os personagens e cores (de vez em quando!) para conseguirmos ler alguma coisa depois. a maneira que o mundo dos sonhos tinha de se preservar era ser esquecido imediatamente pois assim sua força de divinação se concretizava: apenas uma sugestão, nunca uma ordem. hoje a gente anota o sonho em qualquer aplicativo que vai nos dar centenas de estatísticas e interpretações se baseando em folclore (a wiki informal) e dados.

a tecnologia (não só a parte de análise estatística, a escrita por si só também é tecnologia) moldou nossos sonhos individualmente e coletivamente, mas a tecnologia só é influenciada individualmente de volta. de quem são seus sonhos?

around the time yakuza 3 wrapped development, there seemed to be some internal consensus that kiryu shouldn't helm these games on his own anymore; the team thought that some fresh blood could really open up the scope of these games narratively and mechanically and instill a sense of surprise in its audience. and to be clear the series has benefitted strongly from how well it characterizes its protagonists relationships to their environment, but fourteen years later we can safely state that they kind of failed miserably at this task and kiryu is still around. still, this is what makes looking at yakuza 4 and kurohyou interesting - i genuinely have no idea what happened here. yakuza 4 is this insanely unfocused and indecipherable improv mess of 'yes, and' plot developments. you spend the whole game playing through highlight reels of what the dev team thought was cool - they'll hire koichi yamadera specifically to play akiyama ("If Akiyama isn't voiced by Koichi Yamadera then it won’t work! We can't capture his charms!") and then have him make constant metaphors about the animal kingdom, also because they didn't actually have any editors working on the game, they just had a bunch of guys in a room saying 'hell yeah'. they'll walk back pivotal character beats because they don't subscribe to the series' bizarre ideology on who can and can't be a player character. an antagonist will show up in exactly one scene wearing an alternative version of kiryu's suit to show that he's gone full heel and means business. we could literally recap the things that make yakuza 4 ridiculous and i would be here for the next 24 hours.

kurohyou, meanwhile, possesses a jolting sense of restraint. much of this has to do with its comparatively small scope, but even so as an attempt at establishing a new protagonist, there are clear strides to parallel the first ryu ga gotoku. when we first encounter kiryu, he's sacrificing himself by taking the fall for a murder he didn't commit; when we first encounter tatsuya, he's beaten a man presumably to death, and he scrapes up the loose cash he can find and makes a break for it.

all of which is to say that tatsuya starts off as a bit of a psycho - uncharacteristic for this series, to say the least - and the rest of the game is devoted to his character growth. it's parts tournament arc, parts delinquent manga, parts coming of age story, told lovingly through comic book cutscenes reminiscent of those found in portable ops or peace walker. for the most part, it's really solid! no one will be stunned by the direction the story takes but it comes off as tender and earnest; where the fixed camera angles of the ps2 duology reflect its noirish tone, the fixed camera angles of kurohyou's kamurocho evoke a diorama of sorts, befitting of tatsuya's small world and limited interiority. he's a high school drop out who can't really see beyond his fists, and the game manages to eventually channel a level of introspection which feels true to the character.

it sucks that the rest of the game is kind of a first draft. part of why i hold the original yakuza in such high regard is that it's a fantastically realized game that you can wrap up having experienced most of it in between ten and fifteen hours. comparatively, kurohyou has far less to do, but runs for about twice that time. the mini games are much weaker than the standard fare for the series, the absence of taxis makes getting around a bit of a pain, the OST isn't that great, and substories are a notch below the usual degree of quality in spite of how fun tatsuya's interfacing with the world can often be.

kurohyou's strongest draw, then, is its combat - vicious, kinetic, dynamic, and satisfying in ways that the mainline series sometimes can't deliver on. as a def jam fan i felt like i was being pandered to and i'm right at home with AKI/syn Sophia's sensibilities, but it still feels like it's missing something for several reasons. targeting limbs isn't really as important a strategy as it's made out to be; heat faces its most unsatisfying and uninteresting implementation thus far, with nary a hint of resource management to keep players thinking; grabs are too strong for players and opponents alike; for as many fighting styles as there are, some of them are underwhelming and homogenous and all of them are subject to long grinds in order to flesh out; the levelling system is somewhat confused and arbitrary; its differing focus means that some series staples, like long battles, aren't present.

but when it does work...man. so smart to center this game on intimate battles with no intrusion from the UI. performing custom combos and figuring out what works organically instead of queuing up the next tiger drop. relying so strongly on tells in order keep track of your own stamina and to figure out when an opponent might be gassed is a joy. the bosses are a mixed bag because their second phases are all kind of ass, but the bosses that decide to eschew convention via additional parameters (i.e. don't target this opponent's head; you are at increased risk of leg damage) offer very fun twists on the format that you're just not ever going to see in the mainline games.

overall, a great experiment - ten years of thinking about playing this game and now i finally got to play it. satisfying. they should let you cancel attacks using command inputs in the mainline games like they do in this one. sure, they break the combat system on its hinges, but they're pretty fun to execute, no?

kurohyou, meanwhile, possesses a jolting sense of restraint. much of this has to do with its comparatively small scope, but even so as an attempt at establishing a new protagonist, there are clear strides to parallel the first ryu ga gotoku. when we first encounter kiryu, he's sacrificing himself by taking the fall for a murder he didn't commit; when we first encounter tatsuya, he's beaten a man presumably to death, and he scrapes up the loose cash he can find and makes a break for it.

all of which is to say that tatsuya starts off as a bit of a psycho - uncharacteristic for this series, to say the least - and the rest of the game is devoted to his character growth. it's parts tournament arc, parts delinquent manga, parts coming of age story, told lovingly through comic book cutscenes reminiscent of those found in portable ops or peace walker. for the most part, it's really solid! no one will be stunned by the direction the story takes but it comes off as tender and earnest; where the fixed camera angles of the ps2 duology reflect its noirish tone, the fixed camera angles of kurohyou's kamurocho evoke a diorama of sorts, befitting of tatsuya's small world and limited interiority. he's a high school drop out who can't really see beyond his fists, and the game manages to eventually channel a level of introspection which feels true to the character.

it sucks that the rest of the game is kind of a first draft. part of why i hold the original yakuza in such high regard is that it's a fantastically realized game that you can wrap up having experienced most of it in between ten and fifteen hours. comparatively, kurohyou has far less to do, but runs for about twice that time. the mini games are much weaker than the standard fare for the series, the absence of taxis makes getting around a bit of a pain, the OST isn't that great, and substories are a notch below the usual degree of quality in spite of how fun tatsuya's interfacing with the world can often be.

kurohyou's strongest draw, then, is its combat - vicious, kinetic, dynamic, and satisfying in ways that the mainline series sometimes can't deliver on. as a def jam fan i felt like i was being pandered to and i'm right at home with AKI/syn Sophia's sensibilities, but it still feels like it's missing something for several reasons. targeting limbs isn't really as important a strategy as it's made out to be; heat faces its most unsatisfying and uninteresting implementation thus far, with nary a hint of resource management to keep players thinking; grabs are too strong for players and opponents alike; for as many fighting styles as there are, some of them are underwhelming and homogenous and all of them are subject to long grinds in order to flesh out; the levelling system is somewhat confused and arbitrary; its differing focus means that some series staples, like long battles, aren't present.

but when it does work...man. so smart to center this game on intimate battles with no intrusion from the UI. performing custom combos and figuring out what works organically instead of queuing up the next tiger drop. relying so strongly on tells in order keep track of your own stamina and to figure out when an opponent might be gassed is a joy. the bosses are a mixed bag because their second phases are all kind of ass, but the bosses that decide to eschew convention via additional parameters (i.e. don't target this opponent's head; you are at increased risk of leg damage) offer very fun twists on the format that you're just not ever going to see in the mainline games.

overall, a great experiment - ten years of thinking about playing this game and now i finally got to play it. satisfying. they should let you cancel attacks using command inputs in the mainline games like they do in this one. sure, they break the combat system on its hinges, but they're pretty fun to execute, no?

Bravely Default

2013

todo mundo achava que a segunda narrativa criada na história da humanidade seria o (ou durante o) pós-modernismo, se a primeira foi a tragédia grega e seu destino como personagem principal - mal sabiam os estudiosos que o pós-modernismo é a terceira, já que a segunda é bravely default e sua tese sobre a coragem de fazer o que é esperado de maneira consciente, tomando a decisão padrão por brio e não por conformidade, trocando a fenomenologia hegeliana (outro ato de coragem) pela fenomenologia hegeliana (outro ato de omissão).

escrevi mais (em inglês) aqui: https://www.superjumpmagazine.com/bravely-default-as-ergodic-literature/

escrevi mais (em inglês) aqui: https://www.superjumpmagazine.com/bravely-default-as-ergodic-literature/

Bravely Default

2013

O céu como espaço marcado pela liberdade e tingido pela efemeridade da vida; um espaço que as vezes é tão límpido para contemplar, e por vezes tão nublado para observar.

Ace Combat 7 é um jogo que impõem liberdade, efemeridade, contemplação, e, principalmente, a sensação de se adentrar no desconhecido. Sob todo esse contexto, nós existimos como um personagem naquele universo, alguém que - diferente de seus compatriotas - constantemente se joga em meio ao perigo e ao desconhecido, se imergindo entre as nuvens carregadas de descargas elétricas para alcançar o seu alvo e completar a missão. Não foram poucas vezes em que me vi em situações tão extremas e absurdas como a mencionada a cima. São momentos que mesmo ocorrendo em um universo artificial ainda carrega em si o mérito do feito como algo real. Momentos os quais aos poucos vai moldando um mito em cima de nossa imagem: uma lenda entre os demais que representa a sobrevivência.

Mas o que conquistei não foram medalhas de honras pelas minhas ações inconsequentes que regeram os cursos da guerra, ou até mesmo contos heroicos como nas mitologias gregas; o que conquistei foi a liberdade de planar pelo céu; o prazer de rasgar aquele campo azulado com manobras tão deslumbrantes de serem contempladas na perspectiva da cabine; o êxtase em desviar de dois misseis com apenas um único giro para ao final finalizar o seu adversário com um míssil apenas; o medo sentido enquanto contempla o vazio em meio as nuvens para ser recompensado pelo sentimento de vitória por conquistar o desconhecido.

Ao final não me importo tanto pelo mérito ou pelos olhares admirados de meus companheiros; o que de fato quero ser é um com o céu.

Ace Combat 7 é um jogo que impõem liberdade, efemeridade, contemplação, e, principalmente, a sensação de se adentrar no desconhecido. Sob todo esse contexto, nós existimos como um personagem naquele universo, alguém que - diferente de seus compatriotas - constantemente se joga em meio ao perigo e ao desconhecido, se imergindo entre as nuvens carregadas de descargas elétricas para alcançar o seu alvo e completar a missão. Não foram poucas vezes em que me vi em situações tão extremas e absurdas como a mencionada a cima. São momentos que mesmo ocorrendo em um universo artificial ainda carrega em si o mérito do feito como algo real. Momentos os quais aos poucos vai moldando um mito em cima de nossa imagem: uma lenda entre os demais que representa a sobrevivência.

Mas o que conquistei não foram medalhas de honras pelas minhas ações inconsequentes que regeram os cursos da guerra, ou até mesmo contos heroicos como nas mitologias gregas; o que conquistei foi a liberdade de planar pelo céu; o prazer de rasgar aquele campo azulado com manobras tão deslumbrantes de serem contempladas na perspectiva da cabine; o êxtase em desviar de dois misseis com apenas um único giro para ao final finalizar o seu adversário com um míssil apenas; o medo sentido enquanto contempla o vazio em meio as nuvens para ser recompensado pelo sentimento de vitória por conquistar o desconhecido.

Ao final não me importo tanto pelo mérito ou pelos olhares admirados de meus companheiros; o que de fato quero ser é um com o céu.

![NieR Re[in]carnation](https://images.igdb.com/igdb/image/upload/t_cover_big/co7bm4.jpg)