shy

Bio

a fillette révolutionnaire ✿

a fillette révolutionnaire ✿

Badges

Loved

Gained 100+ total review likes

N00b

Played 100+ games

GOTY '23

Participated in the 2023 Game of the Year Event

Trend Setter

Gained 50+ followers

On Schedule

Journaled games once a day for a week straight

Shreked

Found the secret ogre page

Gone Gold

Received 5+ likes on a review while featured on the front page

Well Written

Gained 10+ likes on a single review

Liked

Gained 10+ total review likes

Popular

Gained 15+ followers

Best Friends

Become mutual friends with at least 3 others

Noticed

Gained 3+ followers

3 Years of Service

Being part of the Backloggd community for 3 years

Favorite Games

109

Total Games Played

007

Played in 2024

001

Games Backloggd

Recently Played See More

Recently Reviewed See More

It’s rare that a video game gets a second shot at life. The three weeks after a title’s release is the critical window where most sales are made and the strongest impressions are left. After the proverbial ink dries on the pages of review sites (if you’re fortunate enough to get any) and the chatter dies down, sales gradually taper off to a slow trickle. Unless you’re Nintendo—whose games buck the trend and continue to sell year over year—your options are limited; you can release an update or tack on some DLC for a modest bump, but it only delays the inevitable. However, there’s one wild card that can occasionally bring a stagnant game back from the brink of death: social media trends.

Among Us is doubtless the most famous example; released in 2018 to little fanfare, the Mafia-style multiplayer game exploded in popularity at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic due to popular live streamers setting up games with friends. It was an organic moment in which the game’s appeal was demonstrated by regular people simply playing it and enjoying themselves, free of marketing campaigns, stilted tech demos, or money exchanging hands under the table. These days, with the increased prevalence of streaming, it’s not uncommon for games to get rolled up into the online ecosystem, extending the tail of their lifespan and keeping them in the public consciousness much longer. (This outcome is so desirable that some developers even try to court influencers with their game design choices.) Suika Game is the latest benefactor of these surprise viral trends.

The physics-based puzzler began life as a Chinese mobile game called Synthetic Watermelon (合成大西瓜), spreading through word of mouth via Weibo (China’s equivalent to Twitter) in early 2021. The premise is extremely simple: fruits fall from the top of the playing field, and combining two matching ones creates a larger fruit. Your goal is to continue combining fruit until you create the largest one (the watermelon, of course) while keeping your stack low enough so that it doesn’t spill over the top. The game became massively popular in China, but avoided crossing over to other countries due to the walled garden of Chinese app stores. (Searching Synthetic Watermelon or Suika Game on Western storefronts turns up a bunch of imitators, but don’t download them; they’re all terrible.) Synthetic Watermelon would eventually leapfrog over the Sea of Japan later in the year through an unlikely avenue: a high quality clone version by the company popInAladdin, developed for their line of home projectors as little more than a demonstration of the technology. The new remix on the Chinese mobile hit was modestly popular—enough that the company thought porting it to the Nintendo Switch as Suika Game (スイカゲーム) was a good business move—but it didn’t make waves right away.

Suika Game really started to blow up in 2023, circulating around the Japanese-speaking internet and eventually catching the attention of influencers. Popular livestreamer Futon-chan (布団ちゃん) played it on September 7th, describing it as “a game I often play in my bedroom.” From there, it shot to the moon; VTubers from Nijisanji and Hololive are streaming it for insane amounts of hours, and it’s currently the top selling game on Nintendo’s online storefront in Japan as of writing.

But what makes it such a good stream game? First of all, it’s easy to comprehend; you don’t have to observe for long before you’ve gotten a grasp on the gameplay loop. The goalposts can shift the moment you accomplish a milestone you’ve set for yourself, which keeps you playing for a long time. First, your goal might simply be to make one watermelon; then, you get fixated on making two; after that, you have to beat your high score. It’s also highly competitive, so people that love to backseat are instantly engaged and eager to prove they can put up better numbers. Most importantly, there’s an element of unpredictability. Suika Game is a matching-style puzzler, sort of like a Puyo Puyo or Drop Mania, but the fact that each piece of fruit has physics that affects every other one can lead to amusing and unfortunate consequences. Often, you’ll accidentally launch a tiny cherry off into space and immediately get owned. More opportunities for the player to suffer means more entertainment for the viewer—the popularity of Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy as a livestream game has proven this.

“Stream game” has become a sort of pejorative in certain circles, carrying with it the implication that it’s a better experience to watch than actually play. (These criticisms often get lobbed at things like the Five Nights at Freddy’s series or Tsugunohi—a game that a disingenuous person might describe as nothing but “walking to the left.”) Depending on your values, it might sometimes be the case that you’d rather be the observer than the person at the controls. There’s nothing wrong with that! What makes Suika Game great, though, is that it’s a good time no matter which side you’re on. I enjoy testing my fruit stacking abilities just as much as I do scrolling the game’s hashtag and observing random Twitter users succeed or fail at it. The game’s taken a hold on some of my friends, and it’s been a blast sharing scores and screenshots of my misery. To put it simply: Suika Game is a good stream game because, more generally, it’s a good social experience. It’s fun to share the moment with someone else.

Among Us is doubtless the most famous example; released in 2018 to little fanfare, the Mafia-style multiplayer game exploded in popularity at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic due to popular live streamers setting up games with friends. It was an organic moment in which the game’s appeal was demonstrated by regular people simply playing it and enjoying themselves, free of marketing campaigns, stilted tech demos, or money exchanging hands under the table. These days, with the increased prevalence of streaming, it’s not uncommon for games to get rolled up into the online ecosystem, extending the tail of their lifespan and keeping them in the public consciousness much longer. (This outcome is so desirable that some developers even try to court influencers with their game design choices.) Suika Game is the latest benefactor of these surprise viral trends.

The physics-based puzzler began life as a Chinese mobile game called Synthetic Watermelon (合成大西瓜), spreading through word of mouth via Weibo (China’s equivalent to Twitter) in early 2021. The premise is extremely simple: fruits fall from the top of the playing field, and combining two matching ones creates a larger fruit. Your goal is to continue combining fruit until you create the largest one (the watermelon, of course) while keeping your stack low enough so that it doesn’t spill over the top. The game became massively popular in China, but avoided crossing over to other countries due to the walled garden of Chinese app stores. (Searching Synthetic Watermelon or Suika Game on Western storefronts turns up a bunch of imitators, but don’t download them; they’re all terrible.) Synthetic Watermelon would eventually leapfrog over the Sea of Japan later in the year through an unlikely avenue: a high quality clone version by the company popInAladdin, developed for their line of home projectors as little more than a demonstration of the technology. The new remix on the Chinese mobile hit was modestly popular—enough that the company thought porting it to the Nintendo Switch as Suika Game (スイカゲーム) was a good business move—but it didn’t make waves right away.

Suika Game really started to blow up in 2023, circulating around the Japanese-speaking internet and eventually catching the attention of influencers. Popular livestreamer Futon-chan (布団ちゃん) played it on September 7th, describing it as “a game I often play in my bedroom.” From there, it shot to the moon; VTubers from Nijisanji and Hololive are streaming it for insane amounts of hours, and it’s currently the top selling game on Nintendo’s online storefront in Japan as of writing.

But what makes it such a good stream game? First of all, it’s easy to comprehend; you don’t have to observe for long before you’ve gotten a grasp on the gameplay loop. The goalposts can shift the moment you accomplish a milestone you’ve set for yourself, which keeps you playing for a long time. First, your goal might simply be to make one watermelon; then, you get fixated on making two; after that, you have to beat your high score. It’s also highly competitive, so people that love to backseat are instantly engaged and eager to prove they can put up better numbers. Most importantly, there’s an element of unpredictability. Suika Game is a matching-style puzzler, sort of like a Puyo Puyo or Drop Mania, but the fact that each piece of fruit has physics that affects every other one can lead to amusing and unfortunate consequences. Often, you’ll accidentally launch a tiny cherry off into space and immediately get owned. More opportunities for the player to suffer means more entertainment for the viewer—the popularity of Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy as a livestream game has proven this.

“Stream game” has become a sort of pejorative in certain circles, carrying with it the implication that it’s a better experience to watch than actually play. (These criticisms often get lobbed at things like the Five Nights at Freddy’s series or Tsugunohi—a game that a disingenuous person might describe as nothing but “walking to the left.”) Depending on your values, it might sometimes be the case that you’d rather be the observer than the person at the controls. There’s nothing wrong with that! What makes Suika Game great, though, is that it’s a good time no matter which side you’re on. I enjoy testing my fruit stacking abilities just as much as I do scrolling the game’s hashtag and observing random Twitter users succeed or fail at it. The game’s taken a hold on some of my friends, and it’s been a blast sharing scores and screenshots of my misery. To put it simply: Suika Game is a good stream game because, more generally, it’s a good social experience. It’s fun to share the moment with someone else.

If you’re into retro games, there’s a good chance that you’ve spent some time thinking about the fraught state of media preservation. Maybe you’ve looked up a game you remember from your childhood on the secondhand market and lamented how prohibitively expensive your hobby has become. Maybe one of your favorite games is finally available again after the company holding the rights benevolently decided it was worthy of a remaster, and you wondered why it hasn’t been there all along. You’ve likely at least entertained the idea of downloading a few pirated ROMs. All things considered, the state of video game preservation is currently pretty good.

Organizations like the Video Game History Foundation and Gaming Alexandria work tirelessly to ensure games and supplemental materials are accessible in (mostly) legal ways that are amicable to publishers. By less law-abiding means, passionate amateur preservationists have ensured that the complete libraries of almost every mainstream gaming platform are available, with good tools for emulating them. But for every Nintendo Entertainment System with immaculate documentation, there’s another obscure platform without that community momentum behind it.

Munkiki’s Castles has been a slow work in progress, with preservation efforts beginning in 2017 at the latest. The 2002 Sokoban-style block puzzler with a simian protagonist (the titular Munkiki) was developed by IOMO exclusively for the Nokia 3410 mobile phone—a device not exactly known for its games. The 1.0 version of Munkiki was included with brand new 3410s, but wasn’t part of its stock firmware; Nokia sideloaded the software before shipping the phones out. This is important to note, because resetting the phone wiped the game from memory. Over time, this would reduce the amount of phones holding a copy that could be extracted. To make matters more difficult, the game was dependent on the Club Nokia digital distribution portal for updates. The service was a rudimentary precursor to modern app stores, operating on WAP (Wireless Application Protocol)—a standard for accessing web pages over mobile networks, which was depreciated rather quickly in favor of modern HTML. The 3410 also only had 180 kilobytes of storage, meaning that if you needed to download much else from the Club Nokia servers, you eventually had to make room. Munkiki’s Castles was likely one of the first things to go.

Finding a phone with a copy of Munkiki wouldn’t turn out to be too much of a challenge, fortunately, but a problem immediately presented itself: there was no way to run it when the executable file was recovered. The game’s 3D graphics, which were the first of its kind in a mobile game, were only able to be rendered due to a custom API embedded in the 3410, which supplemented the extremely limited early version of Java ME the program ran in. No progress would be made until the following year, when an update to the FreeJ2ME emulator allowed the game to boot. The emulator’s detailed error reporting pointed to the missing files the game attempted to refer to, allowing the proprietary software to be reverse engineered. Once the game was running properly in emulation, another issue became apparent: version 1.0 was bugged and the game couldn’t be beaten. It wasn’t until mid 2023, when the 1.03 and 1.06 revisions were extracted, that Munkiki’s Castles could be played to completion on anything other than the aging Nokia handset.

For all the effort it took to rescue the game, there’s a difficult truth that must be acknowledged: if more people actually cared about it, the work would have been done much faster. A handful of people obsessed over it in the time they could spare from their busy lives, but Munkiki’s Castles is the sort of title destined only to draw the attention of enthusiasts. It’s the first mobile game with 3D graphics, one of the first games ever released for the Java ME platform, and both of those things are true because of the impressive ingenuity of early mobile software developers—but is the game actually good?

Well. It’s pretty neat, but its relatively simple concept of block pushing with light platforming probably wasn’t impressing anyone in 2002. To put things into perspective: its contemporaries were The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, Grand Theft Auto: Vice City, and The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind. Most people that played it likely thought it was fun for what it was, but put it out of their memory before throwing their old phone into the garbage. It might live on as a vague recollection to a former 3410 owner; they may not even be sure it actually existed.

The double-edged sword with media preservation is that we’re constantly walking a tightrope. Anything you recall can be forgotten just as swiftly. How many times have you found something you misplaced, only to lose it again? The moment something moves out of our collective eyesight, it might as well not be there anymore. Media preservation only works as a community effort because more sets of eyes are trained on the treasures we seek to protect. Seeing how easy it was to collectively forget Munkiki’s Castles, you should feel even more motivated to remember. Throw the emulator into your documents folder and tuck it away safely, the same way you might hang your keys up by the door.

Organizations like the Video Game History Foundation and Gaming Alexandria work tirelessly to ensure games and supplemental materials are accessible in (mostly) legal ways that are amicable to publishers. By less law-abiding means, passionate amateur preservationists have ensured that the complete libraries of almost every mainstream gaming platform are available, with good tools for emulating them. But for every Nintendo Entertainment System with immaculate documentation, there’s another obscure platform without that community momentum behind it.

Munkiki’s Castles has been a slow work in progress, with preservation efforts beginning in 2017 at the latest. The 2002 Sokoban-style block puzzler with a simian protagonist (the titular Munkiki) was developed by IOMO exclusively for the Nokia 3410 mobile phone—a device not exactly known for its games. The 1.0 version of Munkiki was included with brand new 3410s, but wasn’t part of its stock firmware; Nokia sideloaded the software before shipping the phones out. This is important to note, because resetting the phone wiped the game from memory. Over time, this would reduce the amount of phones holding a copy that could be extracted. To make matters more difficult, the game was dependent on the Club Nokia digital distribution portal for updates. The service was a rudimentary precursor to modern app stores, operating on WAP (Wireless Application Protocol)—a standard for accessing web pages over mobile networks, which was depreciated rather quickly in favor of modern HTML. The 3410 also only had 180 kilobytes of storage, meaning that if you needed to download much else from the Club Nokia servers, you eventually had to make room. Munkiki’s Castles was likely one of the first things to go.

Finding a phone with a copy of Munkiki wouldn’t turn out to be too much of a challenge, fortunately, but a problem immediately presented itself: there was no way to run it when the executable file was recovered. The game’s 3D graphics, which were the first of its kind in a mobile game, were only able to be rendered due to a custom API embedded in the 3410, which supplemented the extremely limited early version of Java ME the program ran in. No progress would be made until the following year, when an update to the FreeJ2ME emulator allowed the game to boot. The emulator’s detailed error reporting pointed to the missing files the game attempted to refer to, allowing the proprietary software to be reverse engineered. Once the game was running properly in emulation, another issue became apparent: version 1.0 was bugged and the game couldn’t be beaten. It wasn’t until mid 2023, when the 1.03 and 1.06 revisions were extracted, that Munkiki’s Castles could be played to completion on anything other than the aging Nokia handset.

For all the effort it took to rescue the game, there’s a difficult truth that must be acknowledged: if more people actually cared about it, the work would have been done much faster. A handful of people obsessed over it in the time they could spare from their busy lives, but Munkiki’s Castles is the sort of title destined only to draw the attention of enthusiasts. It’s the first mobile game with 3D graphics, one of the first games ever released for the Java ME platform, and both of those things are true because of the impressive ingenuity of early mobile software developers—but is the game actually good?

Well. It’s pretty neat, but its relatively simple concept of block pushing with light platforming probably wasn’t impressing anyone in 2002. To put things into perspective: its contemporaries were The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, Grand Theft Auto: Vice City, and The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind. Most people that played it likely thought it was fun for what it was, but put it out of their memory before throwing their old phone into the garbage. It might live on as a vague recollection to a former 3410 owner; they may not even be sure it actually existed.

The double-edged sword with media preservation is that we’re constantly walking a tightrope. Anything you recall can be forgotten just as swiftly. How many times have you found something you misplaced, only to lose it again? The moment something moves out of our collective eyesight, it might as well not be there anymore. Media preservation only works as a community effort because more sets of eyes are trained on the treasures we seek to protect. Seeing how easy it was to collectively forget Munkiki’s Castles, you should feel even more motivated to remember. Throw the emulator into your documents folder and tuck it away safely, the same way you might hang your keys up by the door.

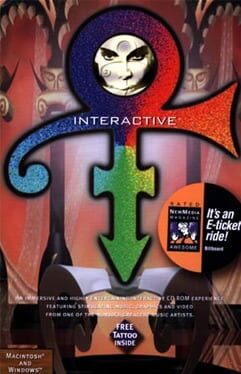

It doesn’t really need to be said that Prince was a living legend. The world renowned multi-instrumentalist maintained a career that spanned four decades, cut short only because of his untimely passing in 2016. There were sharp peaks and valleys in his popularity, like all great musicians, but he consistently managed to catapult himself back into the conversation due to his lightning quick adaptability. When The Revolution—the backing band that helped propel him into superstardom with Purple Rain—dissolved, he didn’t waste any time getting back into the studio by himself. He put together one of the best albums of his career, Sign "☮︎" the Times, while his personal and professional relationships were in a highly mercurial state. In fact, this period was so prolific that the label executives at Warner Bros. had to negotiate with Prince to cut down the length of the album; it ended up releasing “only” as a double LP instead of an absurd triple record affair.

Prince’s versatility wasn’t only limited to his musical talent. His headlong embrace of new technology was undoubtedly a major factor in his unprecedented ability to stave off irrelevancy. He was an early adopter of the Fairlight CMI, a synthesizer that few musicians could even afford in the mid 1980s. Prince’s vault where he hoarded his vast reserves of unreleased music had a DOS-based computer cataloging system on its frontend, affectionately called Mr. Vault Guy, that accounted for the contents of every tape, disc, and hard drive. He was also much earlier than most to the idea of internet distribution, stubbornly insisting on selling the Crystal Ball box set through his own website in 1998, to the detriment of sales.

Given his love for the bleeding edge of progress, it only makes sense that Prince would become interested in video games. In 1994, when Prince Interactive was released, it was yet another volatile period for the artist. To set the stage a little bit: his final album with Warner, Come, was set to release in two months. He purposely refused to promote the new project as a means of spiting the label, ending his contractual obligations by giving them as little profit as possible. He changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol the year before, forcing everyone to call him “The Artist Formerly Known As Prince.” The name of the game, technically, isn’t even Prince Interactive, but we have to call it something!

Cyan’s highly influential Myst released a year prior to Interactive, and the similarities are more than superficial. You find yourself in a fictionalized version of Prince’s home and recording studio Paisley Park, solving simple point-and-click puzzles. Broadly, the objective is to search the mansion and assemble the scattered pieces of the nameless musician’s eponymous symbol as if they’re fragments of the Triforce, though in practice this amounts to a flimsy excuse to poke around and uncover various Prince-related easter eggs. There are an abundance of music snippets, photos, and interviews with other musicians—in which they all heap praise on Prince—to be found. The game even kicks off with an exclusive song called “Interactive,” ostensibly a song about being a song in a video game. (He would pull a similar move years later with “Cybersingle,” a song about the fact that you could download it from the Internet.)

What ends up being most interesting about Interactive is not necessarily how it innovates, but how it’s indicative of its time. Functionally, it does little to stand out from contemporary adventure games like Myst, Beneath a Steel Sky, or Day of the Tentacle. (It’s not even unique as a piece of multimedia artist memorabilia; JUMP: The David Bowie Interactive CD-ROM released earlier the same year.) Historically, it acted as an important document for fans and scribes looking to document the inner workings of Prince’s operation; tours of Paisley Park weren’t permitted while he was alive, and despite all the fantastical embellishments of his Minnesota home, this was the only way to get a surprisingly accurate walkthrough of his studio. Thematically, it tells a story of Prince’s legacy as it stood in the mid ‘90s—full of references to his unassailable accomplishments, but also serving to build up hype for the second act of his career.

Prince’s versatility wasn’t only limited to his musical talent. His headlong embrace of new technology was undoubtedly a major factor in his unprecedented ability to stave off irrelevancy. He was an early adopter of the Fairlight CMI, a synthesizer that few musicians could even afford in the mid 1980s. Prince’s vault where he hoarded his vast reserves of unreleased music had a DOS-based computer cataloging system on its frontend, affectionately called Mr. Vault Guy, that accounted for the contents of every tape, disc, and hard drive. He was also much earlier than most to the idea of internet distribution, stubbornly insisting on selling the Crystal Ball box set through his own website in 1998, to the detriment of sales.

Given his love for the bleeding edge of progress, it only makes sense that Prince would become interested in video games. In 1994, when Prince Interactive was released, it was yet another volatile period for the artist. To set the stage a little bit: his final album with Warner, Come, was set to release in two months. He purposely refused to promote the new project as a means of spiting the label, ending his contractual obligations by giving them as little profit as possible. He changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol the year before, forcing everyone to call him “The Artist Formerly Known As Prince.” The name of the game, technically, isn’t even Prince Interactive, but we have to call it something!

Cyan’s highly influential Myst released a year prior to Interactive, and the similarities are more than superficial. You find yourself in a fictionalized version of Prince’s home and recording studio Paisley Park, solving simple point-and-click puzzles. Broadly, the objective is to search the mansion and assemble the scattered pieces of the nameless musician’s eponymous symbol as if they’re fragments of the Triforce, though in practice this amounts to a flimsy excuse to poke around and uncover various Prince-related easter eggs. There are an abundance of music snippets, photos, and interviews with other musicians—in which they all heap praise on Prince—to be found. The game even kicks off with an exclusive song called “Interactive,” ostensibly a song about being a song in a video game. (He would pull a similar move years later with “Cybersingle,” a song about the fact that you could download it from the Internet.)

What ends up being most interesting about Interactive is not necessarily how it innovates, but how it’s indicative of its time. Functionally, it does little to stand out from contemporary adventure games like Myst, Beneath a Steel Sky, or Day of the Tentacle. (It’s not even unique as a piece of multimedia artist memorabilia; JUMP: The David Bowie Interactive CD-ROM released earlier the same year.) Historically, it acted as an important document for fans and scribes looking to document the inner workings of Prince’s operation; tours of Paisley Park weren’t permitted while he was alive, and despite all the fantastical embellishments of his Minnesota home, this was the only way to get a surprisingly accurate walkthrough of his studio. Thematically, it tells a story of Prince’s legacy as it stood in the mid ‘90s—full of references to his unassailable accomplishments, but also serving to build up hype for the second act of his career.